When big changes hit, how can photographers document them? Do they have a responsibility to cover the news headlines, or are there other approaches? In the latest addition to an ongoing series bringing together two creatives of different generations to discuss capturing change, Diane Smyth talks with Magnum Photos’ Ian Berry and Bieke Depoorter

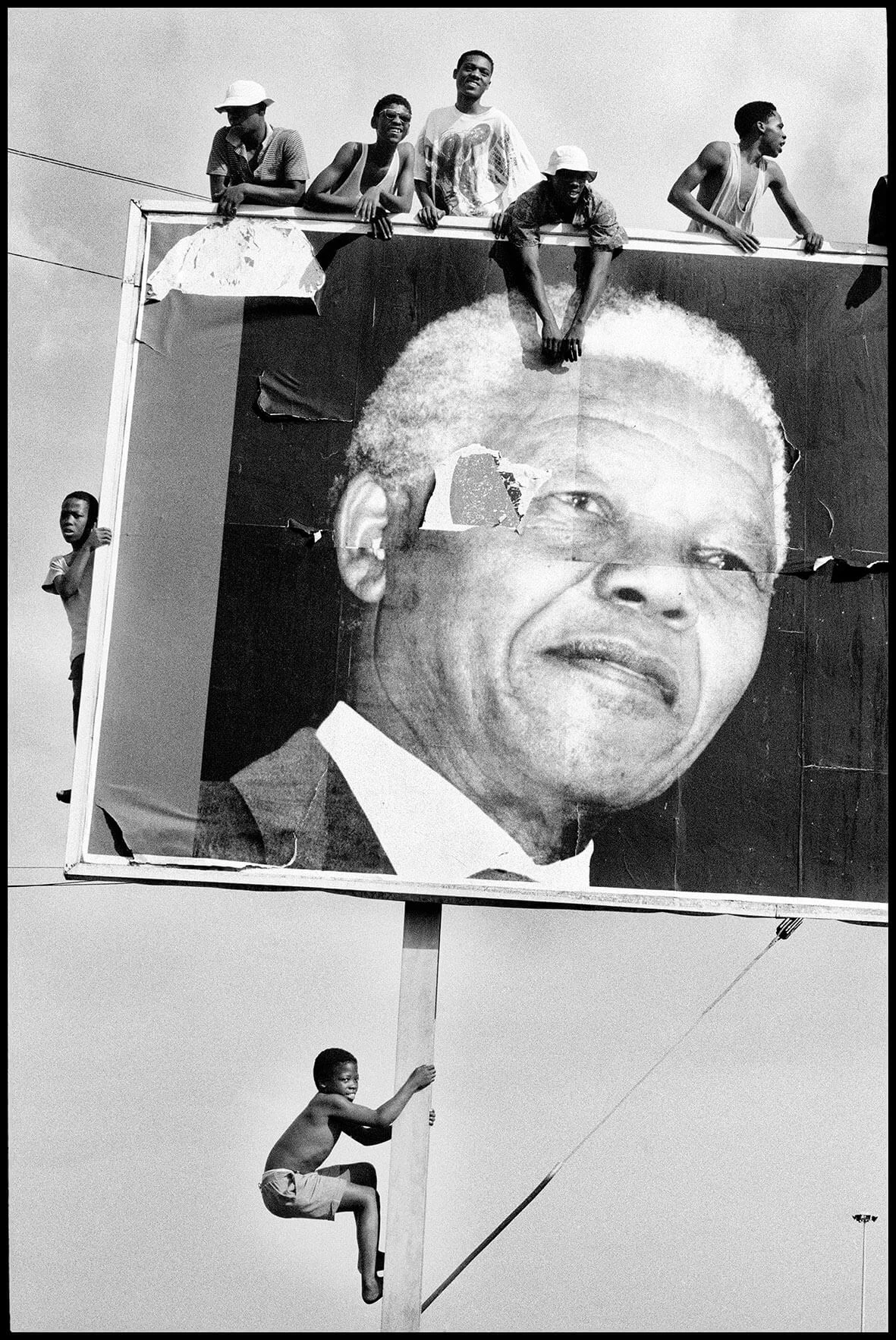

It’s a truism but currently we’re all experiencing it: change is the only constant. Societies and environments are continually evolving and occasionally erupt into era-defining shifts, and that’s something photographers Ian Berry and Bieke Depoorter have both experienced first-hand. Bieke was on the ground in Egypt in 2011 during the Arab Spring protests, for example, and Ian documented the massacre at Sharpeville, South Africa in 1960, in which the police shot and killed 69 peaceful protestors. It’s not the only thing they have in common – both are highly successful, both made their names while still in their early twenties, and both are members of the prestigious Magnum Photos agency. But in other ways they couldn’t be more different, with widely varying approaches to both photography and to documenting the world with it. Ian is motivated by a desire to “show people on one side of the world what was happening to people on the other side of the world,” he says; Bieke opts to focus on the small-scale and the intimate.

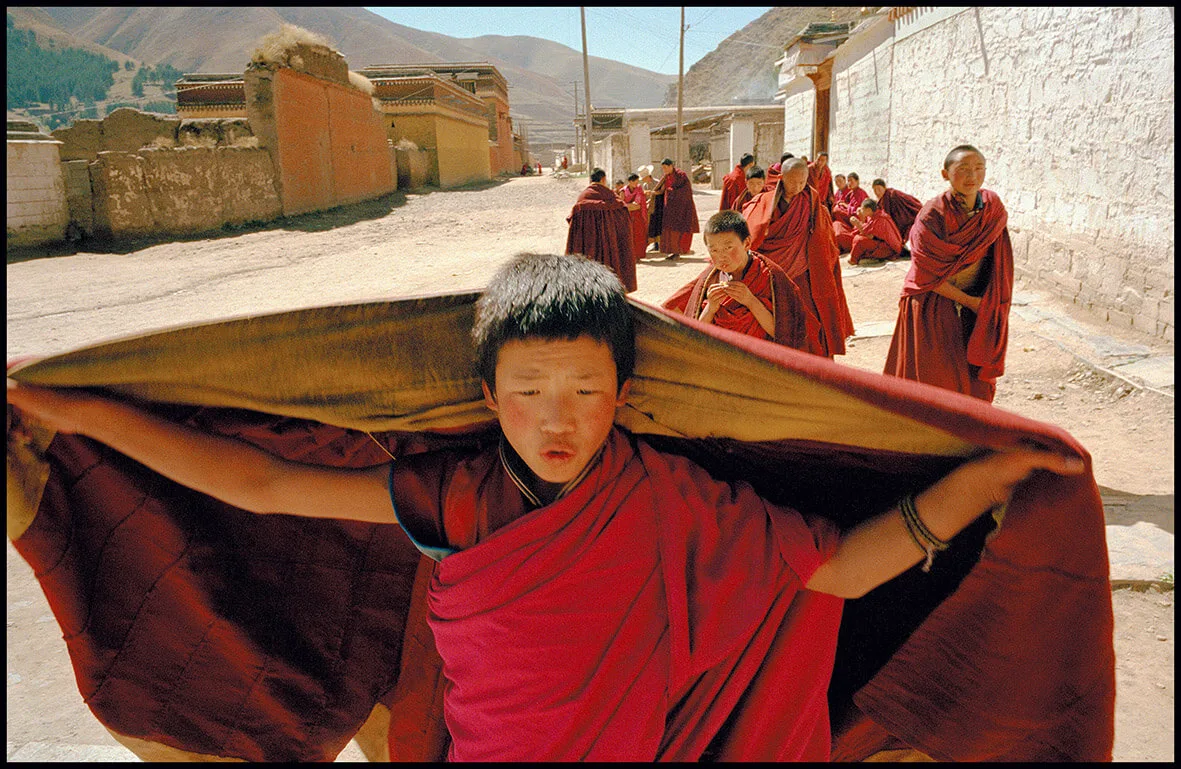

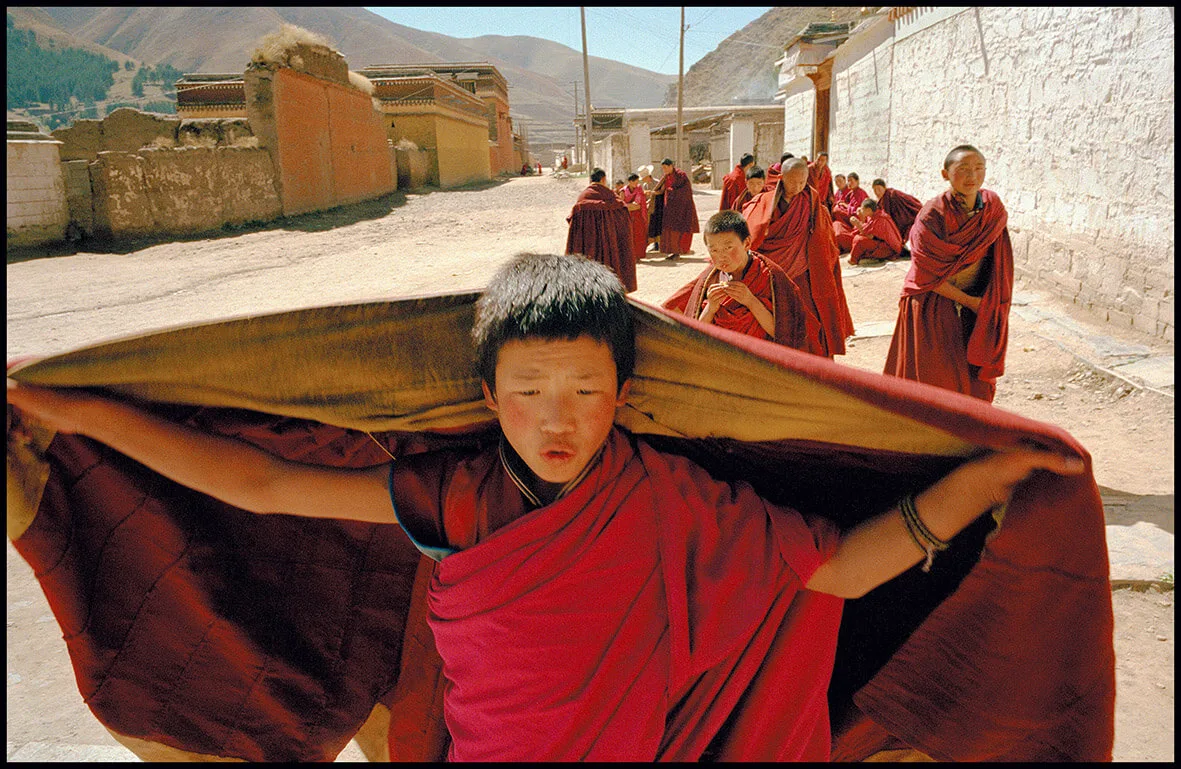

Born in Lancashire, England, Ian photographed Apartheid in South Africa for nearly four decades, and was the only photographer to document the Sharpeville Massacre. His images from Sharpeville went on to be used as evidence in the trial to prove those wounded innocent. Ian has shot for publications such as the Observer Magazine, Paris-Match, National Geographic, and Life, working all over the world on stories such as the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. He has also shot long-term projects, most notably in South Africa but also in countries such as Ghana, China and the UK, and has published many books.

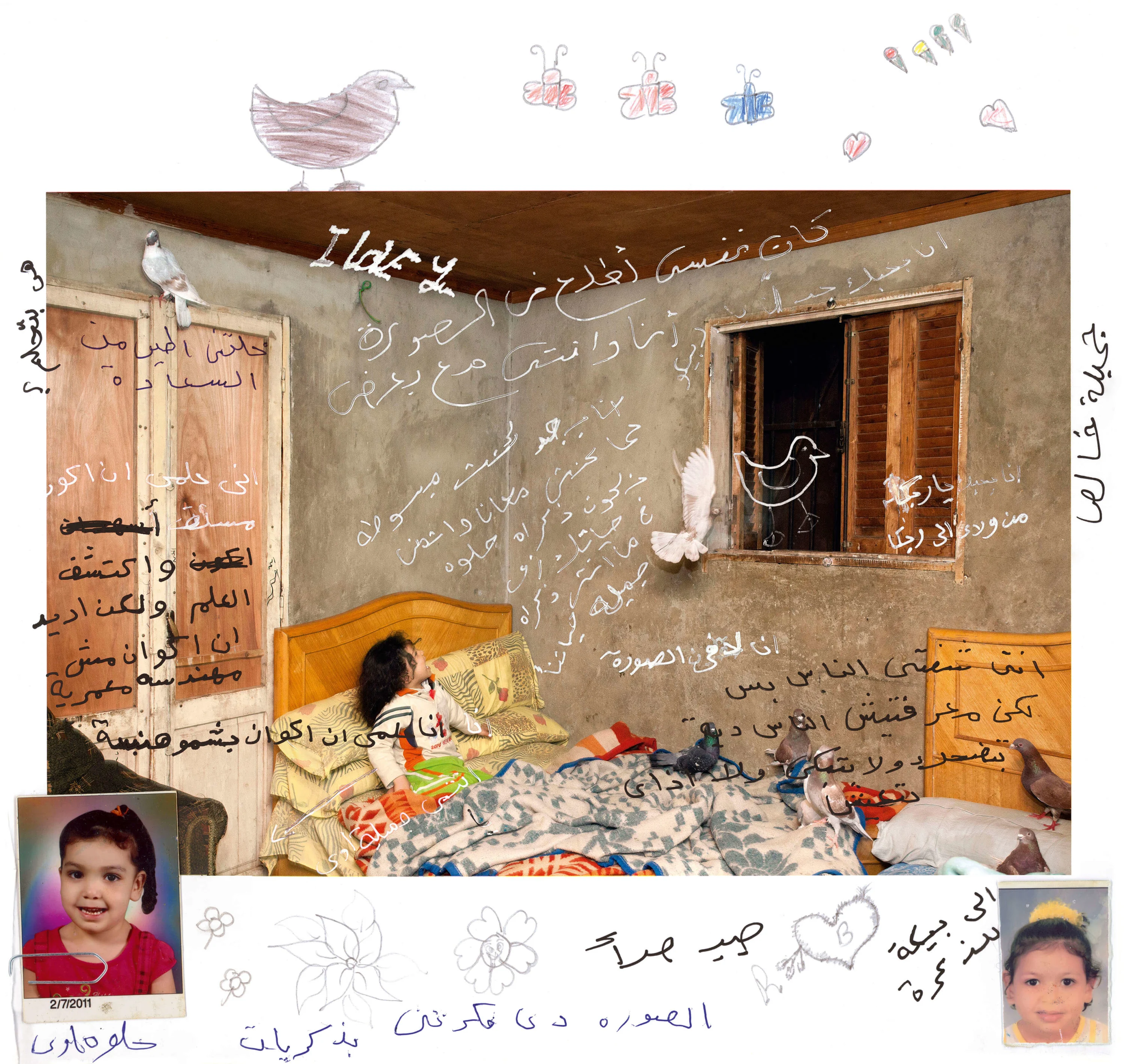

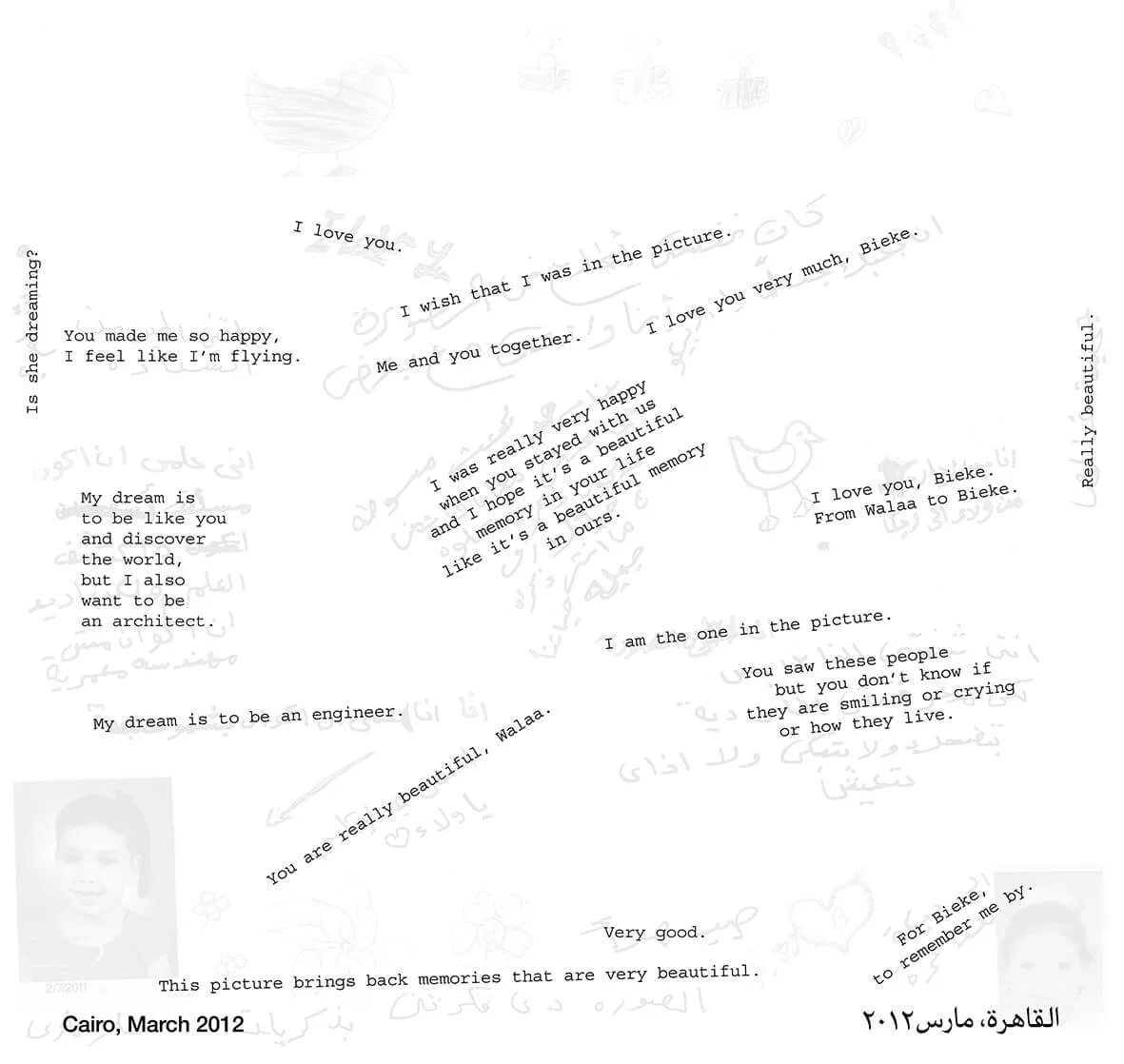

Bieke was born in Kortrijk, Belgium in 1986, and graduated with an MA in photography from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Ghent in 2009. Her first book, Ou Menya (2012) was shot in the homes of Russian strangers, with whom she stayed for just one night; I Am About to Call it a Day (2014) was shot in strangers’ homes in the US. Her third book, As It May Be (2017) was also shot in strangers’ homes, against the backdrop of the Arab Spring in Egypt from 2011-2017. The publication includes comments written directly into the book dummy by other Egyptians, offering their perspectives on her work. In other projects, such as Sete 15 and Agata, Bieke has collaborated with her subjects, creating characters and roles with them.

On shooting big news events

Ian: I was 16 when I first went to South Africa. It was really by accident – when I left school I wanted to travel, and South Africa was one of the places you could go with a cheap Commonwealth ticket. To be honest I had no idea what life was going to be like when I lived there. and then I realised what it was like to work for an African magazine. I’d go out with an African journalist and he couldn’t even go into a restaurant to have a cup of tea; at night, if we were travelling, I’d stay in a local white hotel and he would have to go off and find somewhere to sleep in the local township. So it all came home to me very rapidly what was happening in South Africa.

Photographing Sharpeville was a turning point for me. There were no great pictures there – people were just being shot and I photographed them being shot around me. But what was amazing was how long things went on afterwards before real change. The country shut down for a few days in shock but then it rapidly recovered and just went on as before. I think the government was initially a bit shaken but then they got it together, and they had the treason trial, they locked up people like Mandela. Eventually it became obvious I couldn’t continue working in South Africa and in the end I was banned.

Bieke: The first time I went to Egypt, I was asked to do something in Cairo with three other Belgian photographers, working towards a book and exhibition. We decided to do something in the shadow of the revolution, not really photographing Tahrir Square or the protests but the background. After three times visiting Cairo this assignment was finished, but I felt the project was not over for me. The revolution was still going on and the situation was so complex, and I really wanted to go to smaller places in Egypt. So this assignment turned into a personal project for six years.

When I first arrived, as I always do if I arrive in a new place, I wandered around in different neighbourhoods of the city. I didn’t really know what I was doing, I just wanted to feel the city and see what I would do. People were friendly and giving me tea, and maybe they let me into the first room in the house. But they never let me in the back of the house, and taking photographs was super difficult because of religion, culture, and – I felt also – the revolution. I became very curious about what was behind those closed curtains and doors, and I thought, “I came here not thinking I would do this project ever again, staying the night in people’s homes and trying to find trust, but I feel I should try it here because it looks like it’s impossible to find trust in this place.”

In the years 2015-16 it was almost impossible to find a place to spend the night, people often didn’t let me in because they thought I was a spy. It became very complicated. But even though it was complicated, if something political happened, I didn’t photograph the politics happening outside. I would go inside people’s homes in the area. I followed the revolution in a different way. My Egyptian project was the closest I came in being a photojournalist because I felt a responsibility not to ignore what was going on. But it had to be in a way I thought was right for me.

On their approach to photography

Bieke: I feel I’m quite a selfish photographer, I tell stories by starting from myself. I feel guilty about it sometimes. For example, now what’s going on with COVID-19, in the beginning I was so imbalanced. I felt like I wanted to capture it, I wanted to be helpful by photographing what’s going on, by going to hospitals or photographing people who are really dealing with this on the frontline. But then, at the same time, it’s not how I cover things. I have another approach. For a moment I thought to be really helpful I’d have to leave photography aside for a while.

I think it’s important to document , but I also think I’m not the photographer who is very good at this. There are many different kinds of photographers and stories can be told in different ways, from different angles. In a small story, you can cover something really big – in those very individual stories, focusing on a little detail of conflict, you can also talk about the bigger conflict, or put the bigger thing in another perspective. I think it’s also important to do that.

In my work, I often feel that I’m not so much interested in showing the differences between people as the similarities. I think in general if we want change, or if we want people to recognise themselves in the other, then this is really important. In the end we all want the same things. We all want to be close to someone we trust and to feel safe.

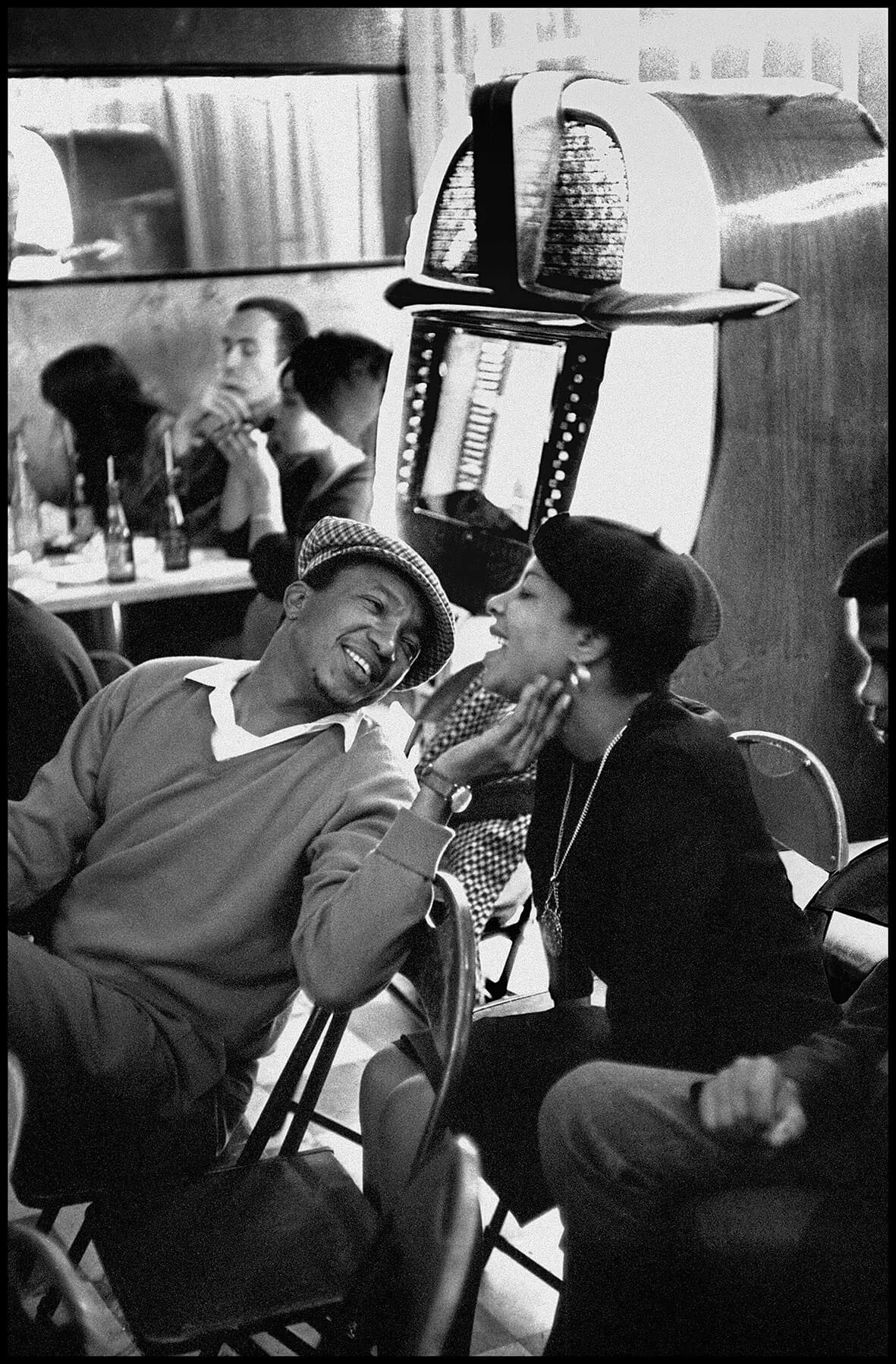

Ian: When I joined Magnum, we regarded ourselves as having common social interests in what was going on in the world. We were all left – not Left with a capital L – but left-thinking in how we wanted to look at what was going on. We wanted to show people on one side of the world what was happening to people on the other side of the world. Henri Cartier-Bresson said to me once, “Really we’re hunters...we move unobserved and the skill is not just picking up the moment but making a shape out of that.” That’s always been my main purpose. I’m frankly not interested in navel-gazing – I’m looking at what’s there and trying to portray it in the best way I can.

Of course as a photojournalist you get involved in life and people; if you’re doing a major story for a magazine, you get behind the scenes. That’s what we do, it’s not just what’s happening directly in front of you. But you have to make it interesting for other people to look at. I’m interested in people and how they live, and in trying to show that in a way that’s going to be interesting for the reader – showing it in a way that’s going to draw their attention, even if they don’t consciously recognize it’s a good shape.

We wanted to show people on one side of the world what was happening to people on the other side of the world

On being an outsider

Ian: It was actually much easier for me to work in South Africa because I was always perceived by the black South Africans as a foreigner. If your hair was a little bit longer and you were a little bit weedier and couldn’t be suspected of playing lots of rugby, you were viewed as a foreigner and probably therefore a friend. That also meant it was much easier for me to work with the Africans than with the police – I had to be careful when I was around the police. But the black South Africans took me into their homes, into their shebeens, I had no problems. It was the same in Prague in 1968 – the guys on the tanks, the Russian soldiers, would try to stop you. They would fire in the air and you would run away and they would run after you, and the crowd around would sort of open to let you through and then close to stop the soldier chasing you, or you’d get onto the street and someone would put an arm out of a house and drag you inside. Again, as a foreigner you were on the Czech side.

Bieke: Being a foreigner and a photographer could be dangerous . In a sudden moment for example, there were warnings on TV saying foreigners could be spies. Journalists were put in prison, things happened to foreigners, so I actually didn’t take my camera out often in the streets. But I think it also meant people let me in more quickly. I feel Egyptians are quite protective about their personal life, but being a foreigner made it easier to get in.

I worked with a translator and we would walk around for hours and hours and hours to find a family that accepted us, who trusted us and who we trusted. My translator would explain the project and that I was a photographer and making a book, because I find it really important to say what I’m doing, and for people to accept being in a book and an exhibition. She would also make it clear I was not a spy, that was very necessary. But then she would leave and I would stay alone. I want to photograph by myself, and I find that people change if I do. I also like the idea of not having a common language, because the interaction is totally different. Without language, the interaction is all about trust and observing each other and being together. At the same time, I think it’s really, really important to have insiders as well as outsiders to cover a conflict. We see this now in Magnum Photos – I feel we are an important agency and so it’s crucial to diversify and have insiders to talk about certain events. For example Lindokuhle Sobekwa, one of the Magnum associates, makes incredibly important and good work in South Africa. He was one of my first students when I was teaching in Thokoza. It’s so important to have his photographs as well.

On being a fly on the wall

Ian: If I’m shooting I try to be in there before they see me, and I might get two or three shots. If they then see me, I will smile, and take a couple of pictures just to show I don’t wish them any harm. But I was shooting in a village in Bangladesh and it was really difficult because they haven’t seen a foreigner in years, and the kids all rush around and what have you. So you sit for a morning, longer if necessary, until everyone gets bored of you and carries on with their lives, they lose interest in you finally. Then, if you’re quick, you have a possibility of getting something out of it visually, of getting a photograph. Then you can work.

Bieke: I really don’t believe in the “fly on the wall” photographer. For me, photographers have to be aware that, though we may look invisible, I don’t think we are, especially if we photograph inside people’s homes. I think it’s an illusion to be a fly on the wall because the fact that we’re there is already changing the whole scene. I think this is a really important thing to realise as a photographer. It’s important to show your position and to be aware of your position and not to try to hide yourself in your story, because we are there. We are part of the story in a way. Also it’s totally fine to have your own point of view on something. There’s always a person behind the picture and that’s ok. I think you are able to seem invisible in a photograph by not trying to be when you are photographing.

I don’t think we are, especially if we photograph inside people’s homes. I think it’s an illusion to be a fly on the wall because the fact that we’re there is already changing the whole scene.

On changes in their process

Bieke: The project changed over the years. After seven years you change as a person and as a photographer, your way of thinking changes, your approach changes, and the revolution continues to evolve. In the beginning I thought it wouldn’t be possible to go into people’s homes but actually, almost every night I found a place to stay. But by 2016, the last time when I went to really photograph, I only found one place to sleep in three weeks. It changed on many levels.

I started to become more and more aware of my position as a photographer, and I felt like although I engaged with the people, I was very much an outsider. I felt I was photographing them from a Western point of view, or I was aware of the fact people would see those pictures also from a Western point of view. I couldn’t stand the idea that people would have their thoughts about the images, thoughts that would probably not be how people in Egypt would see them. I wanted to publish the book – I had a publisher lined up – then I decided “I can’t publish this book, this is not the truth, whatever that is. It doesn’t show the complexity of the country at all.”

That’s why I went back with a dummy copy of the book, to let other Egyptians write comments directly onto the photographs. Contrasting views on country, religion, society, and photography arose between people who would otherwise not often cross paths. This way I also wanted to include people into the book who would never let themselves being photographed. So if you see my image without the comments or with the Arabic that people don’t understand here and then you read the translation, your thoughts about the same image are totally different. I like to play with this theme of a shifting interpretation of the same photo.

Ian: I guess I’m not smart enough to change my life, but I’m still able to make a living doing what I do, which is much the same as what I’ve always done. My interests are much the same as they always have been – I want to show what’s going on in the world. But I don’t know how soon it’s going to be before I can next go to China [because of the Covid-19 virus and the associated lockdowns).

I’m most interested in finding parts of the world I haven’t photographed before, but that’s becoming increasingly difficult. When you’ve travelled for 100 years running around the world, you’ve been everywhere. But places I know less well interest me more – or places I photographed 30 or 40 years ago, I’m more interested in going back there. The juxtaposition there is China because it’s evolving so rapidly, it’s changed so much since the first time I went. That’s fascinating for me.

I’ve been pursuing a project involving water, and I’ve gone around the world photographing it up and down the Yangtze, the Mekong, the Nile, the Mississippi…Things are changing. I mean countries like Bangladesh might not exist any more in my lifetime because of climate change. When I first went to Bangladesh they were exporting rice, now they’re importing it because the water table has changed, the typhoons come further and further inland every year. Mexico City is an enormous city, it has an incredible population, and they’re going to be importing the water within the next 20 years because the water table is running out. That’s the sort of thing that fascinates me now.