The comic book industry has often been called into question for its lack of representative characters, from gender to race to sexuality. This year it was announced that Marvel will feature its first openly gay character in the upcoming The Eternals movie, but back in the ‘80s there was one comic book already leading the charge. First published in 1980 Gay Comix featured work and stories by the LGBTQ+ community that focused on issues not discussed in mainstream press and provided much needed information at a time when the AIDS crisis was never far from mind. Ryan Cahill meets the people behind the publication to unearth its important history.

The comic book industry has undeniably stood the test of time. You only have to look at the likes of Marvel and DC Comics to see the long-lasting cultural impact. Only last year, Forbes reported that Marvel alone was set to surpass a networth of $5billion, accumulated through the box office, comic sales and Marvel merch. But despite the fanfare surrounding the comics, there still remains an issue with diversity; namely a distinct lack of queer characters both between the pages and on-screen. In 2018, GLAAD even went as far as to publicly criticise Marvel and DC comics for their lack of representation, saying, “It is becoming increasingly more difficult to ignore that LGBTQ people remain almost completely shut out of Hollywood's big budget comic book films that have dominated the box office over the past several years.” Shortly after this, it was announced that Marvel’s upcoming flick The Eternals would feature the first openly gay superhero, played by Brian Tyree Henry.

As a publisher in a field dominated by white men, I encouraged work from women and minority cartoonists but by the late ‘70s it was still very rare to see work by openly gay cartoonists.

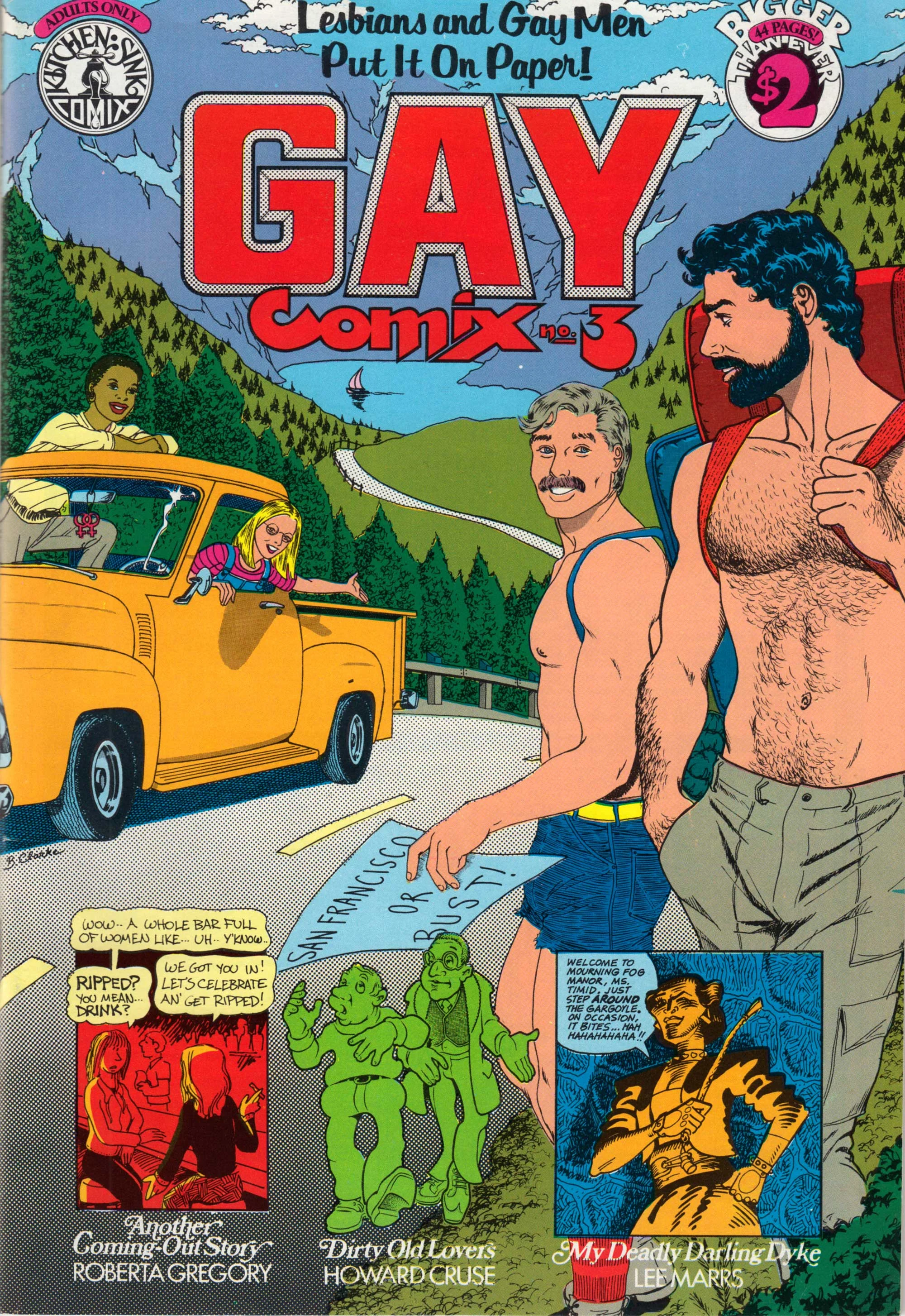

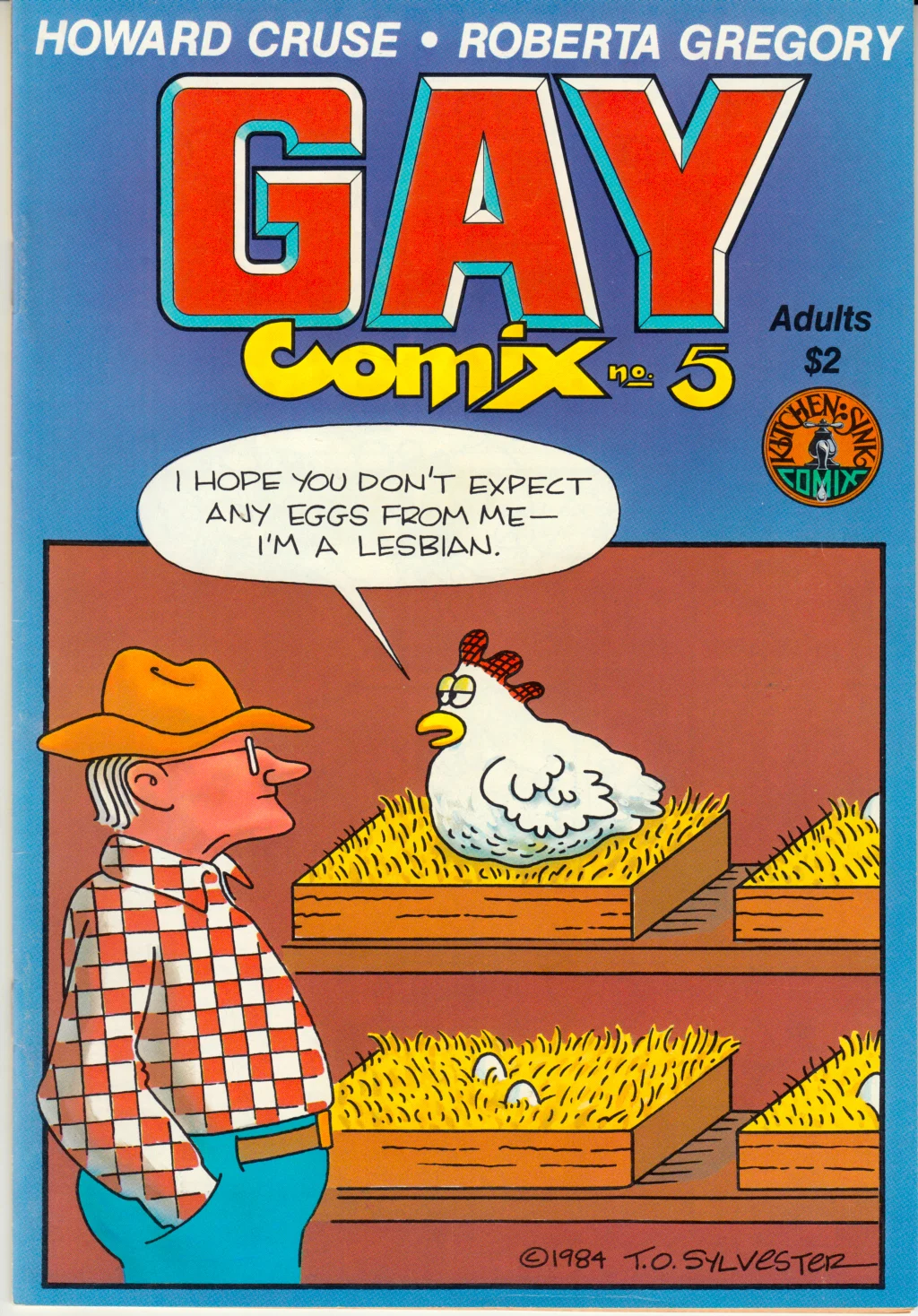

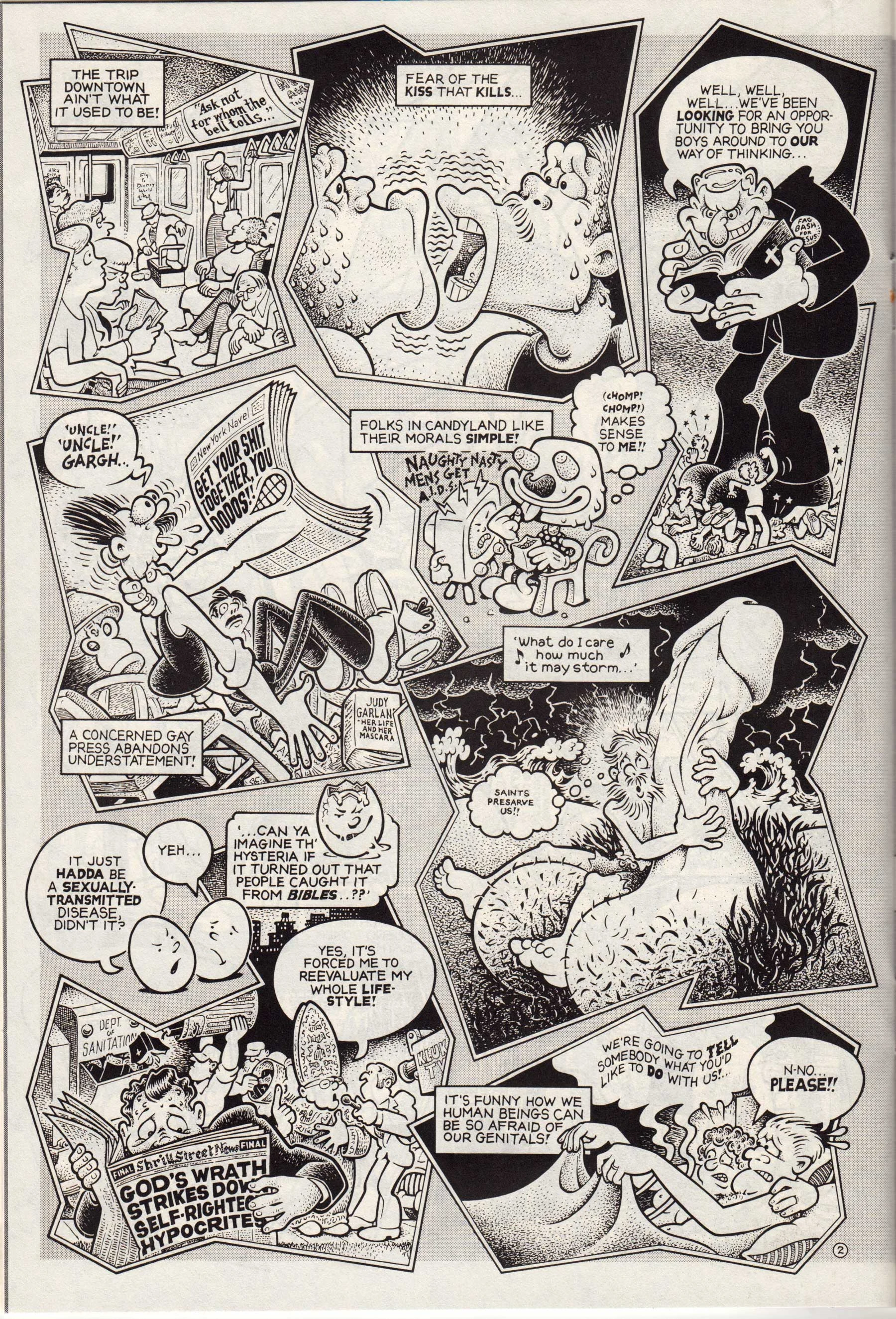

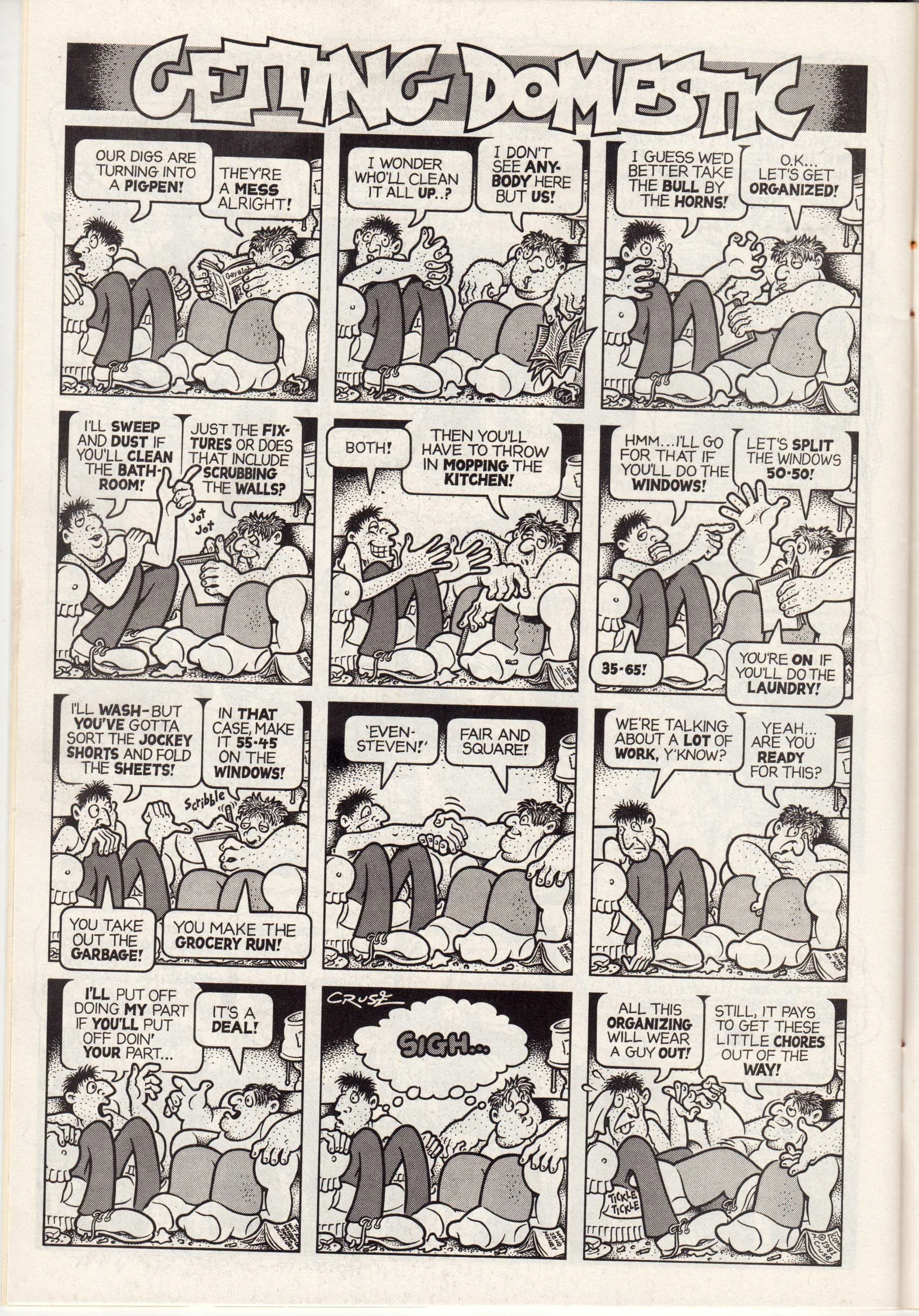

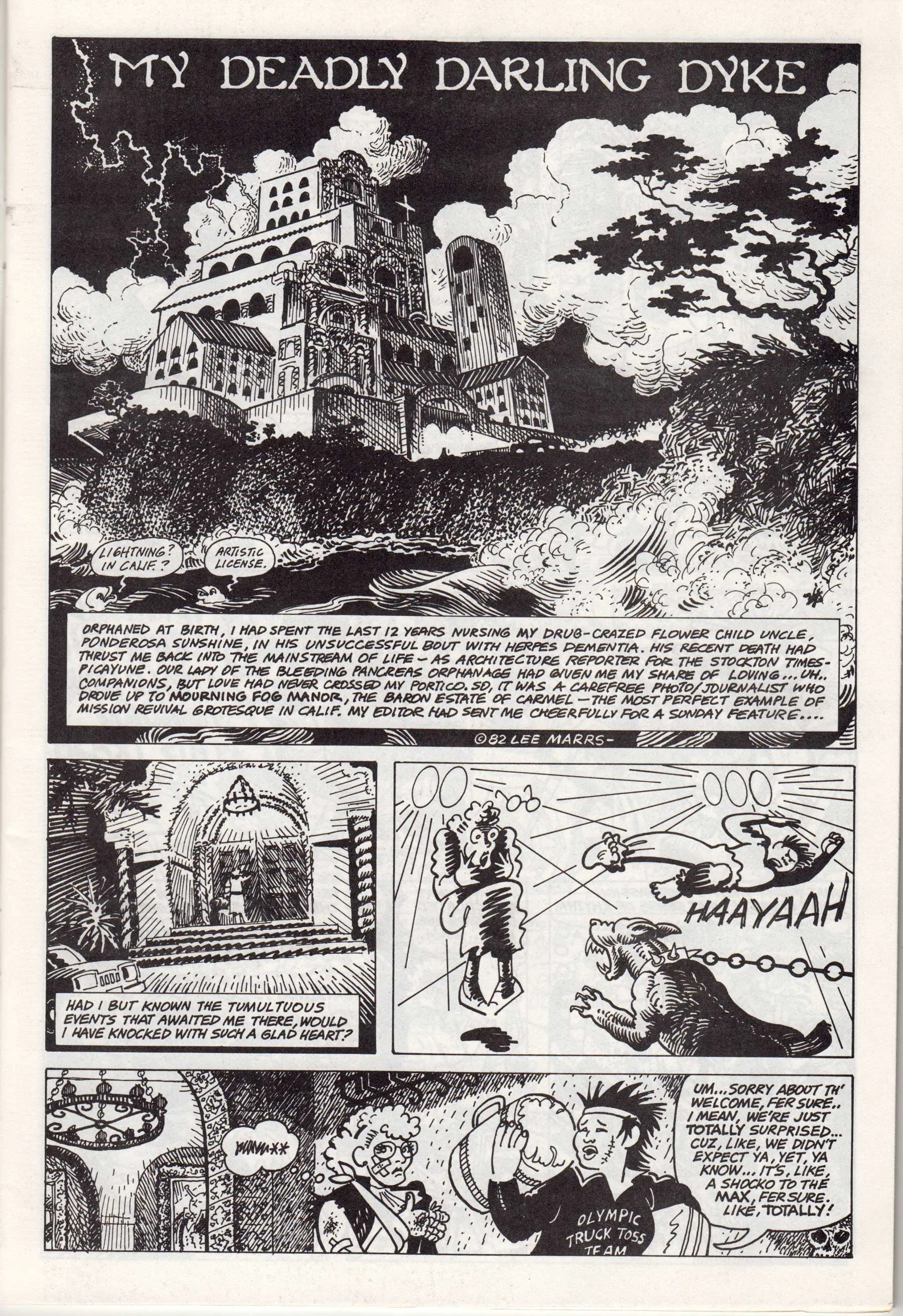

But back in the ‘80s amidst the AIDS crisis, there was one underground comic book that was seeking to turn the tide on the ever-present lack of representation. Simply named Gay Comix (the X was a connotation for the underground culture), it had exclusively queer storylines and was produced almost entirely by gay men and women. It proudly brandished the tag line: “Lesbians and Gay Men Put It On Paper!” At the time of its inception, it was distributed by Denis Kitchen of Kitchen Sink Press, a publisher based in Wisconsin responsible for putting out underground comics including Bizarre Sex and Bijou Funnies.

“As a publisher in a field dominated, like so much, by white men, I encouraged work from women and minority cartoonists but by the late ‘70s it was still very rare to see work by openly gay cartoonists,” Denis explains. Now 74, he still retains his passion for comics despite his publishing house closing at the end of the ‘90s. “I had been publishing Barefootz Funnies by Howard Cruse and for some years he’d been a regular contributor to my anthologies like Snarf, Bizarre Sex and Comix Book,” he says. “I had noticed a gay artist named Headrack appearing in Barefootz, and it occurred to me that Headrack might be an autobiographical element. In those pre-internet days I wrote to Howard, who I think was still living in Birmingham, Alabama, deep in America’s Bible Belt. Paraphrasing, I said, ‘Howard, no offense intended, but might you be gay?’

“He wrote back that he was, but professionally closeted. I proposed a comix anthology by gay cartoonists and asked if he would consider editing it. He initially responded that he’d love to see such a publication, but feared that coming out would harm his primary career as a freelance illustrator. After thinking it over for a while, though, he agreed to take it on.”

“Howard confessed that he didn’t know any other gay cartoonists,” Denis continues. “Neither did I. So we agreed that I’d send out a form letter on Kitchen Sink stationery to every artist in my rolodex, announcing Gay Comix and asking any gay men, lesbians, and bisexual cartoonists to send submissions to Howard. A few recipients were not at all happy to get such a letter, but much positive support came back and some very pleasant surprises too.”

Howard Cruse (who sadly passed away in 2019) was arguably the backbone of the Gay Comix. Having established himself as a budding cartoonist in the ‘70s, Howard utilized much of his own personal experience and embedded it into his stories for the publication. It was the first instance in which he had openly addressed his own sexuality in his work, and led him to create the acclaimed strip Wendel (for gay publication The Advocate), which told the story of a gay man and his partner Ollie. It also gave him a platform to address many subjects which directly affected his community, including AIDS, gay rights demonstrations and gay bashing.

For many, Gay Comix became not only a source of entertainment, but a place where you could find vital information about gay life in the ‘80s. Flipping through its pages, it perfectly captures and successfully satirizes much of the sociopoltical queer issues that were taking place at the time. Rather than specifically suggest the content they wanted, editors would instead give illustrators the freedom to input whatever it was they wanted to explore or discuss, which ensured the collection had a wide range of diverse stories that touched every corner of the LGBTQ+ community.

I got the printing-plate negatives back and found Biblical references written in the margins.

The publication went through quite a turbulent journey over the course of its 18-year run. After five years of printing, Denis found that the cost of producing Gay Comix was disproportionately higher than any of the other titles that he published, in part due to the complex distribution system and distinct mailing devices that were entirely separate from the other comics under the Kitchen Sink Press umbrella. “It was also difficult, if not impossible, to stretch my limited advertising budget to effectively promote Gay Comix to its primary reader base when everything else I published could be efficiently promoted and pushed via the comics industry’s ‘Direct Market’ system,” he says. “I increasingly felt that Gay Comix would best benefit from being with a gay publisher who knew that specialty market far better.” It was this mindset that cemented Denis’ decision to sell the title. “I connected with Bob Ross, who owned the Bay Area Reporter which was a weekly gay paper in San Francisco, and when he expressed interest in acquiring the title in 1984 it seemed like a good match. I sold him the trademark, the only thing I owned, since the copyrights, like all undergrounds, were retained by the respective creators.”

Robert Triptow, a cartoonist and writer from Utah, edited the magazine from 1984 until 1988. He experienced publishing under both Kitchen Sink Press and Bob Ross. His journey to becoming the editor was a peculiar one, starting when he noticed a review copy of the publication in the bin while working at the Bay Area Reporter. He managed to persuade the editor to let him write a feature on it. For this, he reached out to Howard Cruse for some quotes and in return, grateful for the coverage, Howard asked if he knew any cartoonists for a list he was working on for the new issue.

Robert sent him some "Castroids" strips that he’d done which had been rejected by every gay publication in California, but Howard replied, "At last! Somebody with some chops!"

Everyone seemed to love the concept and the content and most thought a venue for gay cartoonists was long overdue.

“It floored me,” Robert says. “I'd never thought that highly of them and he used them in issues two and three.” After that though Robert didn’t draw anything for the magazine and instead concentrated on an "underground" story in Bizarre Sex which he calls “the fulfillment of my teenage hippie fantasy.” But when Howard announced his retirement from the Gay Comix editorship in 1984 Robert asked Denis Kitchen who the next editor was going to be. “It was just casual and Denis wrote back thanking me for my interest in the job and offering the editorship to me. What? Wait a minute. What?!” I thought.

“It took me a couple of weeks to respond,” Robert says. “I feared it would cause me trouble, especially with my family, and I was right. At that time I was working in advertising and already spending too much time at a drafting table. I didn't particularly enjoy the drawing side of the job but I had no desire to be ‘famous’ in any way. I had just fled LA after watching my friend Charlene Tilton's life change due to Dallas and before that I'd been the assistant to David Goodstein who was publisher of The Advocate, during the year of Harvey Milk. Their feud was featured in the movie Milk and I was in the middle of all that. I really just wanted to be a local writer quietly living with my boyfriend in fabulous San Francisco.”

After much contemplation though Robert said yes to the job, recognizing that if they were offering it to him, there was likely nobody else to take up the role. He also believed he could bring something new to the series, having seen “plenty of the darker side of the gay movement.” “I'm sarcastic by nature too. I had edited newspapers, written press releases, designed advertising. I thought humor could be very useful in the fight for rights.”

Despite his successful tenure as editor of the magazine, it’s not something Robert feels entirely comfortable thinking back on, citing it as a “dark time” in which many of his friends were being “cut down by AIDS.” It also wasn’t the easiest role for him to execute, echoing Denis Kitchen’s remarks, he admits that publishing Gay Comix wasn’t an easy feat. “One surprise was our first printer, who did a shoddy job. I got the printing-plate negatives back and found Biblical references written in the margins.”

“The other big problem for me was that editing was very burdensome. The job became more and more demanding. It was a time of death and depression,” he says. “My family was outraged by Gay Comix. My straight friends were in a different reality, happily raising small children and my gay friends were dying. I was HIV negative but in bad health myself. And the publisher was difficult to work with. Impossible, in fact.”

Although people recognize the cultural significance of Gay Comix today, Robert admits he didn’t notice it at the time it was published. “Gay Comix made no cultural impact at all during the time I was editing it, as far as I could tell,” he says. “It never sold more than a few thousand copies. Mainstream papers like The San Francisco Chronicle never mentioned gay cartooning once until 30 years later. The gay community was rather preoccupied at the time with AIDS. I was completely unaware of Gay Comix having any following at all until the internet came along.”

Denis Kitchen, however, has a different outlook: “As a straight guy I was never exactly plugged into the gay community, so my feedback came indirectly via Howard, some contributors, and the direct and wholesale customers who reached out to us. I know that we had almost universally positive responses from people we heard from. Everyone seemed to love the concept and the content and most thought a venue for gay cartoonists was long overdue.”

While the relevance of Gay Comix may not have been aparent at the time, it’s clear to see the positive impact it’s made today. You could even argue that it still remains to be ahead of its time, given the lack of queer characters and storylines in mainstream comic book culture today. As early as their third edition, Gay Comix was printing stories about a trans man depicted as living a normal life and in happy, committed relationship. There was another that explored the highs and lows that come with in being in a lesbian relationship. Elsewhere a feature explored illegal love under oppressive governments, while a particularly forward-thinking piece looked at the use of different pronouns. Published over 30 years ago, these are topics that we welcome and champion today, but back then they were undoubtedly taboo to discuss.

For queer comic lovers, the niche publication offered a form of escapism that wasn’t readily available to them. Both educating and entertaining, Gay Comix captured the imagination of a marginalized community and gave them the otherwise absent information they required at a time when they were being internationally demonized. What was the significance of the comic to queer people at the time? Robert Tripow puts it simply: “All I know is that I used Gay Comix to lighten things during scary times. And that's always the role of art.”