The way that Esiri Erheriene-Essi talks about images is very intense. They’ve always been prevalent in her life, whether she was using old family photographs to learn about her own history and identity or interning at picture desks for magazines and newspapers. Today, she bases each of her mixed media paintings on old photographs that depict everyday scenes from the lives of black families in the 1950s and ‘60s, showing them in vibrant technicolor where the old film cartridges of the time failed to do so. She tells Alex Kahl about the process, intention and meaning behind recreating the mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers of these found photographs.

Located in a building where almost every room is put to use by an artist of some kind, Esiri Erheriene-Essi’s studio in Amsterdam is a bright and spacious one. Daylight streams through four floor-to-ceiling windows, pouring light onto walls covered with canvases, some barely touched and others that seem close to completion. It’s a studio that’s seen tens of canvases come and go in the last year, since Esiri was nominated for the Prix De Rome in 2019, one of the Netherlands’ most prestigious art awards. The four nominees are given from May to September to create a series of works to be exhibited in the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. Not used to working in series and having not painted at all for over a year since having a son, Esiri panicked a little, but the deadline gave her a rush. “I was just excited to be back,” she says. “I had been in this mother zone, overwhelmed with emotions, and with this I could just leave that hat at the door and become Esiri the painter again.”

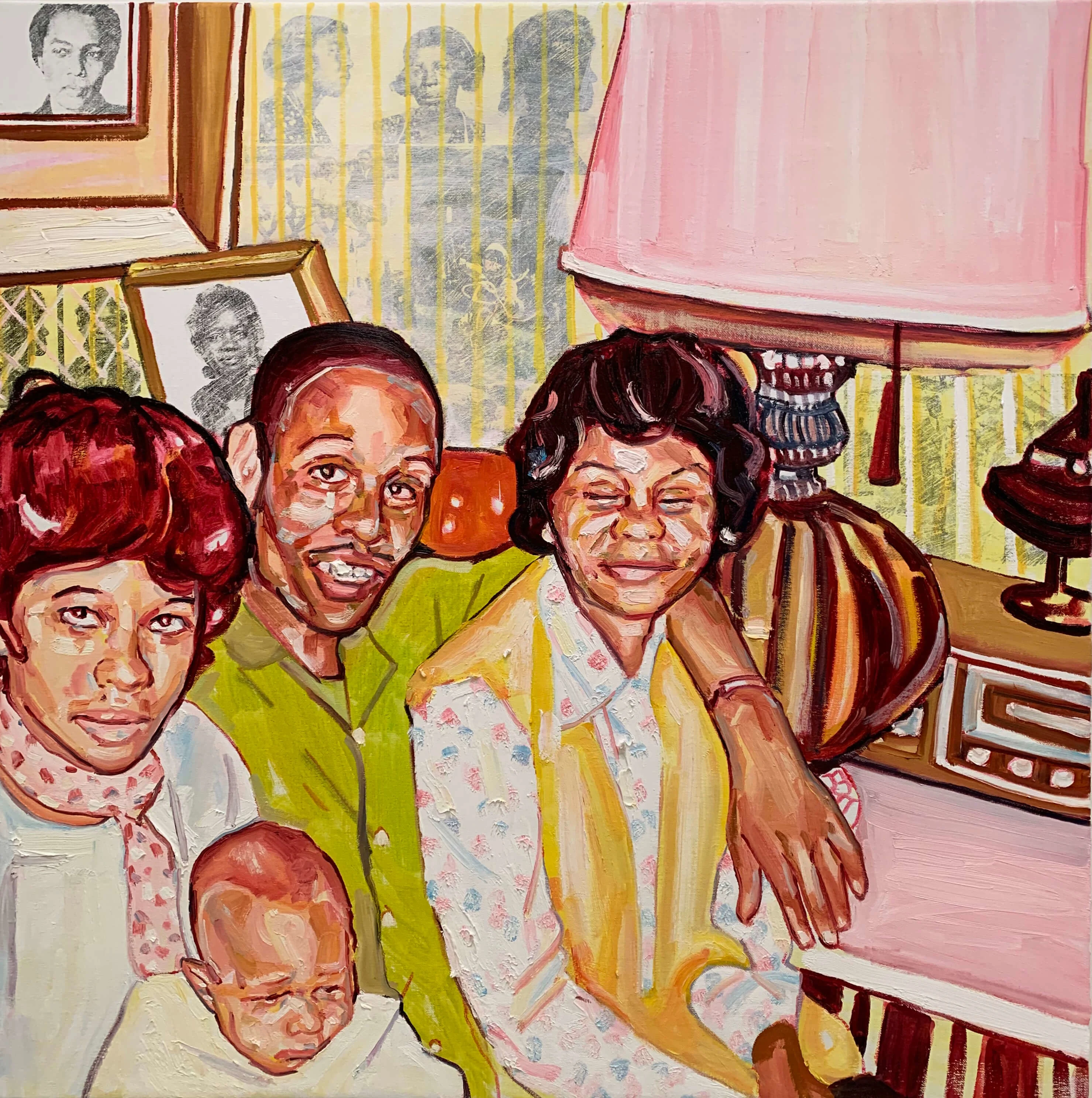

After working tirelessly for four and a half months, Esiri emerged with The Inheritance, a series of large-scale pieces, colorful and textured depictions of everyday scenes, each entirely based on real photographs from the past. From birthday parties to trips to the fair, she shows the ordinary moments in the lives of black families.

One reason Esiri likes to base her work on old imagery is because of the inherent racism that was in the photographic technology in the 1950s and ‘60s; the old Kodak film’s inability to capture the nuances of black skin tones is well documented. Esiri references a story about Jean-Luc Godard, who refused to use Kodak film on a shoot in Mozambique because he argued the film stock didn’t do justice to people’s appearance. “It would almost look like a Kerry James Marshall painting,” she says. She takes these old photographs and recreates them, using layers of oil paint to give texture and depth to the intricacies of the characters’ faces. “I wanted to use that technology and reclaim it and give prominence to the skin tones,” she says. “I want to bring these people back into technicolor, where before they were flat and one-dimensional.”

I’m a person who reacts to an image and uses that to take it somewhere else.

Esiri spends time exploring flea markets and vintage shops, looking for photos from the mid-20th Century to inspire her work. She even has a photograph “dealer” who sells her images she might like. “I’m a person who reacts to an image and uses that to take it somewhere else,” she says. She often projects the photograph onto the canvas, and traces over the outlines, using acrylic ink to get the base layers set, before using oil paint for the rest of the process.

She loves the idea that she can bring these historical scenes into the present, and make these forgotten figures time travel in some way. “History is not just something from the past. It’s in all of us, it’s in our names and our language and the way we look at things, in the way we look at the world and understand it,” she says. In her paintings, she depicts these people from past generations, who seem so distant but in fact paved the way for so many things. “I’m always fascinated by what has come before. How we got here, the legacies that were left, how we materialized. We didn’t just come out of thin air, there was a whole history of people that were involved in our lives that have brought us here,” she says.

Esiri always had a personal relationship with images. She covered her bedroom walls with posters like any other teenager, but she was really drawn to family photos. She speaks of how images have always transported her somewhere else, a sensory overload sending her into the world in the frame. Her parents had brought their own photos and mementos from Nigeria, and Esiri would use these to discover her own personal history.

She never really knew her grandparents, but these photos gave her a way into their lives. “When you’re in London, you sometimes think the world is that small. But you see these photos of other places that look so different, so exciting and so technicolor, it reminded me almost of the world in The Wizard of Oz,” she says. Her love of images comes from making sense of the world through them. “I would make up characters and stories for the people in the photos,” she says. “When you see your parents existed before you were there, you see that they’re fully formed individuals and not just mum and dad.”

Esiri grew up in London and was raised by Nigerian parents who moved there in the ‘80s to study. As a child, her mum would take her to museums on the weekends or in the holidays. “Museums were all free, so I never felt excluded from that world, even coming from a working class background,” she says.

She used to draw all the time growing up, and art and literature were her favourite subjects at school because they came naturally to her, but she never really took art seriously until her secondary school teacher gave her a Basquiat book because he thought she might like it. “And I fell in love,” she says.

History is not just something from the past. It’s in all of us.

It was only when Esiri visited Florence and saw Michelangelo’s David and burst into tears that she really saw art’s emotional impact. She would be blown away by a Lucien Freud painting and would break the rules to take a photo, bringing it back to her teacher filled with anger and jealousy and asking how she could make something like that. “Before then, art was either good or bad to me, it was great to look at and it was fun, but in those two instances I really saw the power that it could have.”

While interning at a magazine, an editor told her about De Ateliers, a funded two-year art residency program, and she applied. Two months late and sending 100 images when 20 were requested, she still managed to get an interview, and in turn a place on the program in Amsterdam.

“I came to Amsterdam the following September, and it was then that I had to figure out who I was as a painter,” she says. “London is great because there’s so much inspiration and noise and so much happening, and Amsterdam just isn’t the same. It was much quieter and I had a lot more space to think.”

Esiri had been painting, in a comic style, funny scenes involving her friends. With space to think, it was clear to her that the images she had always loved needed to play a bigger part in her work. She uses various techniques to transfer photos and images onto her canvases, to sit amongst the painted bodies of the works. She does this for brand logos for example, using a xerox transfer, which is a 24 hour process. “You have to really stick the image on to the canvas with the glue, and then wait 24 hours for it to dry, then use water to peel the paper, and the layers of printed image and glue will be left.” She points to a large pile of shredded paper. “All that came from just making this one A3 canvas.” She also uses acetone to make some transfers, sticking an image on the canvas and using nail polish remover and a pencil to transfer it onto a piece. This technique allows her to decide on the quality of the transfer, so that she can make posters that sit in the background of the scenes seem faded and old.

Esiri’s fascination with her own family photographs speaks to her obsession with the concept of memory, but she’s also aware that the complexities of memory often don’t align with the way history is taught and remembered. She recalls enjoying history classes at school, but remembers being taught about topics like the formation of the catholic church or the roman empire, with no lessons about colonialism or about the different cultures that made Britain ‘great’. “In history books, there’s these set transcripts of the past, but there’s always things that are left out of the equation. It’s taught in a linear structure when memory isn’t like that, it’s always jumping all over the place,” she says. “My parents were the ones who told me that we’re here because Britain was there, and this is the mother country. And that resources have been depleted there. My mum didn’t want to leave. You’re hearing these two different views and you’re having to make sense of it.”

Esiri’s mundane, everyday scenes from black lives are so important simply because of their mundanity, since this side of life for these people was just not seen at the time. “It’s not as if black people all around the world existed in a vacuum, and just came out in the ‘50s. We’ve been around, but it’s not been documented because it wasn’t deemed important,” she says. “I really wanted to have black people existing on canvas doing everyday things. The banality of that. Not always having to resort to struggle or death or stereotypes. That’s not all our lives are about. There’s also joy, there’s also boring aspects.”

In this way, Esiri’s paintings make a socio-political comment in a subtle way, but there seem to be more overt references to these themes in some of the works. Some of the characters wear badges in support of the Poor People’s Campaign, and posters of Angela Davis hang in the background. Although this seems to be a clearer point in the direction of the socio-political situation of the time, Esiri once again intends to come at these issues from a more mundane, everyday perspective. “I always think, what about the everyday people who weren’t the face of the campaign but were still supporting?” she says. “Wearing the badges, donating, turning up at the rallies. I’m fascinated by the people who pushed these histories but weren’t publicised for it. You always get the big shots of Martin Luther King or Malcolm X, but you rarely get the photos of the people who watched them and cheered for them.”

We are human, we are different, but there are a lot of similarities.

People sometimes ask Esiri why she doesn’t paint her own family photos, but there’s something about images of unknown people that keeps drawing her in. She borrowed the idea of “familiar strangers” from Stuart Hall, one of the cultural theorists she studied at University. “He talked about familiar strangers that people from the African diaspora have, wherever they are in the world. There’s a bond, regardless of where you’re from,” she says.

She hopes that people of all backgrounds and races can feel a connection to these paintings, though. “I’m seeing these characters’ history. I find a connection, and I really wanted that to be what people felt when they saw people on the canvas. We are human, we are different, but there are a lot of similarities. And it’s interesting to see the things we share. The common ground,” she says.

Esiri hopes that whether or not people recognize themselves in the faces on the canvas, the feeling of family and togetherness and mundanity will spark something in everyone. “It’s a way of making people recall their own memories, and to give people an entry point when they’re standing there looking at the work,” she adds.

As much as she hopes to ignite certain responses, Esiri can’t predict the ways in which people will respond to her work, but this uncertainty excites her. For her, each image she’s ever looked at throughout her life has transported her somewhere else, and she hopes she can create this same feeling for at least one other person. “There’s so much I want to condense into these works. How can I catch people’s senses but also capture these scenes that haven’t been documented and tell forgotten or neglected stories, while also keeping things fun yet simple yet profound? I don’t know how you do all that in one painting, but once I figure it out I’ll probably quit!” she says. “Until then, each painting is just a way of trying to discover something new.”