The artist paints the childhood he left behind in Cuba

As part of the Mariel boatlift in 1980, Cuban-American artist Edel Rodriguez, at just nine years old, moved with his family from their native Cuba to the United States, with little more than the clothes on their backs. In the subsequent years Edel began work as an art director before establishing himself as an artist and illustrator working for the likes of The New Yorker, The New York Times and TIME magazine – where his illustration of Donald Trump as a flaming, screaming fireball received international attention.

But even as Edel’s star in the art world rose, his home country of Cuba and all that he left behind as a child was never far from his mind. It’s an all too familiar story that has gained new poignancy in our recent times, and one that depicts the human side of immigration and loss. In this specially commissioned feature Cuban-American journalist Rebecca Sanchez follows Edel as he returns home for the first time in almost a decade, bringing the gift of creativity back to his beloved Cuba.

It’s nearly noon when the plane kisses the asphalt and comes to a screaming halt at the José Martí International Airport of La Habana. Already it is 98 degrees and the heat makes its presence known in undulating translucent waves that rise from the ground and can be seen from the window, before you even enter into them.

The Embraer E175 may be small as far as planes go, but on June 23 its cargo is far greater than its size lets on. In a stroke of serendipitous precision, the flight has just carried Idania del Rio and clan, of Clandestina — Cuba’s first independent fashion brand — renowned Cuban Conguero Pedrito Martinez and family, and Cuban artist Edel Rodriguez from Newark to Havana. It is a titanic delivery of artistry returning to the island all together, if even for just a few short hours, before everyone disperses and disappears into the old city.

For Edel, getting through the airport is no small detail — a fact that reveals itself in stacks of documentation and two passports clinched in his hand. Still, it is not enough. He is held briefly when the agent asks for a third passport he doesn’t have on him, but after a few minutes it seems she loses interest and grants him entry. Outside, Edel’s favorite aunt Nancy and cousin Liset rush toward him in anxious excitement. It’s been years since he has seen them and several rounds of hugs take priority before heading towards the car sitting in wait, trunk propped open by a sawed off wooden bat. Inside it there is only a spare tire and a machete.

Packing into the car, we set out, embraced by black and indigo velvet, which still pristinely envelops the firmly cushioned seats. Havana may be the destination for the very many tourists that visit the island each year — it is, in the end, part of the lure of the Caribbean that Edouard Glissant referred to, its being situated at the outer edge of space and time. And if Havana really exists as a city in Cuba, it is only under such a condition — encapsulated by isolation, in a distorted preservation that collides with the performance of cultural plurality, for the sake of an industry for foreigners. It exists as caricature.

Tourists may have claimed its beaches but the dirt has never been up for grabs, and Edel is today headed directly to a place where that dirt and its dust span out across vast and open horizons.

“Did you paint the house?” Edel asks his aunt from the front seat, knowing the answer.

“How well I prepare for you,” she replies cheekily. Though, the truth is, Liset painted the house — something she does every time Edel comes home.

“I want to paint the reality here — real life,” he says after a brief pause.

“Oh, you want to paint the reality,” she nods, “well good then, that’s exactly why I painted the front of the house and left the side untouched.

“There’s your reality,” she laughs.

The road out of Havana to El Gabriel is beset by signs that seem to be speaking to no one. Phrases declaring all loyalty in unity to the revolution, pledging fidelity to the notion that there is always more that can be done on behalf of the country, committing the remembrance of legacy to May 1 all appear only as memories, recalled only to themselves — the public gaze having fallen away so long ago it’s like it was never there in the first place. The walls and billboards, faded and decayed as many are, may as well be blank.

Horses graze along the uneven street, decorating sparse countryside that is otherwise kept company only by fruit stands and small outdoor bars, but there is, at this moment, a beer shortage, so we keep it moving.

These rural roads haven’t changed in the nearly 40 years since Edel left, though his experience of them has. As a child, he says, driving through the dark desolation of the fields at night inspired a particular kind of eeriness. Today, he’s more amazed that the trees are all exactly the height they were all those years ago — a thought he considers curiously, wondering how they maintain themselves so evenly — and marvels at the stark contrast between this eternal sameness and the pathological fluctuations of the Miami and New York City skylines.

In some ways it is as though this preserved landscape is its own monument, histories hidden in the sinewy guts of sugarcane and buried deep like roots grown into the earth, the fissures of which are betrayed by the unfolding of a horizon multiplying into the distance. It is here, in the paradox of all that has remained the same while also always being somehow different — where the soil is suddenly red like fire, like the sun’s heat that it guzzles and interfuses, red like blood spilled — that we find the reality of Cuba, and it is here that Edel’s art begins, just as Glissant says: “The storyteller’s cry comes from the rock itself. He is grounded in the depths of the land; therein lies his power.”

The sight of a timeworn, decaying sugarcane factory is the sign that we are almost there. After all, it was the factory that came before the town, enabling the community whose livelihood formed around it. Edel hasn’t been home to El Gabriel since 2015, and even then it was only for a day or two, off the back of a work trip to Havana, so when he arrives it is not without fanfare.

The welcome party is at first primarily a swarm of mosquito stowaways that burst into a frenzy when the front door of his aunt’s place opens, disquieting the air of the dark, shuttered house. The swarm is quickly followed by homemade guava cake — a story in itself — fresh tamales and back-to-back visitors, in between each of which he announces, “We’re going to head over to Nilda’s house.”

Nilda is Edel’s neighbor and the mother of his best friend, with whom he shared a backyard growing up. But it’s not until the next day that we finally make it over.

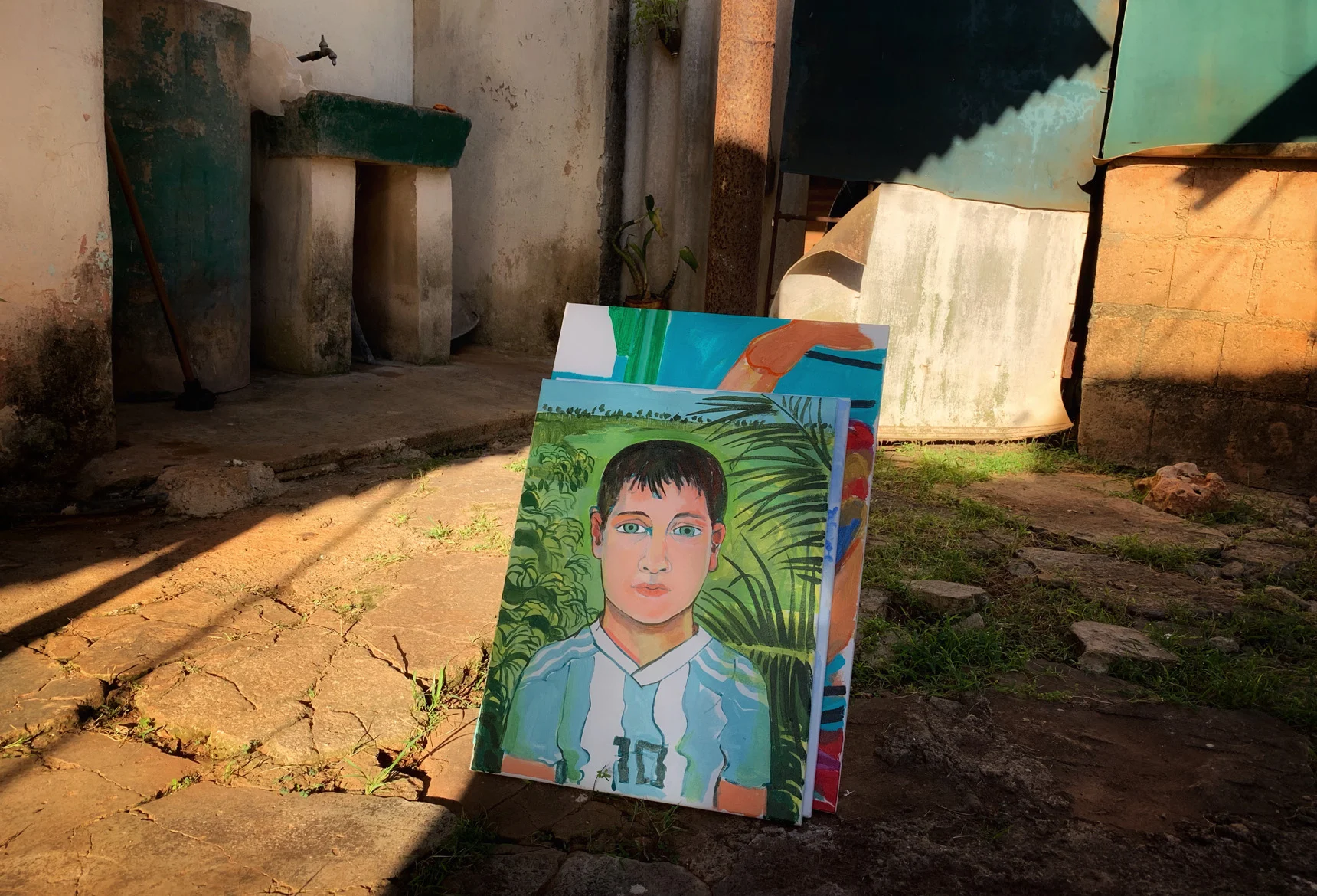

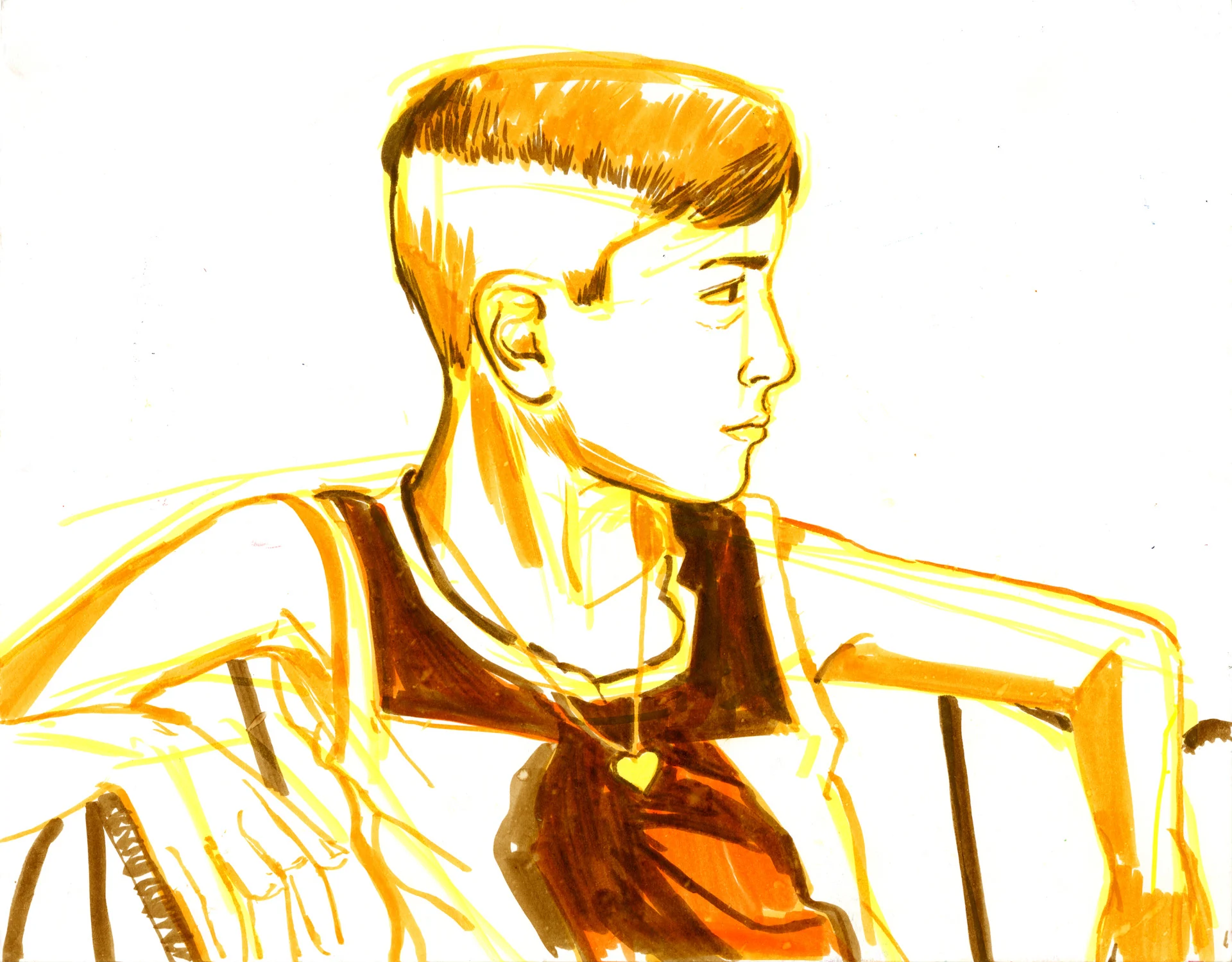

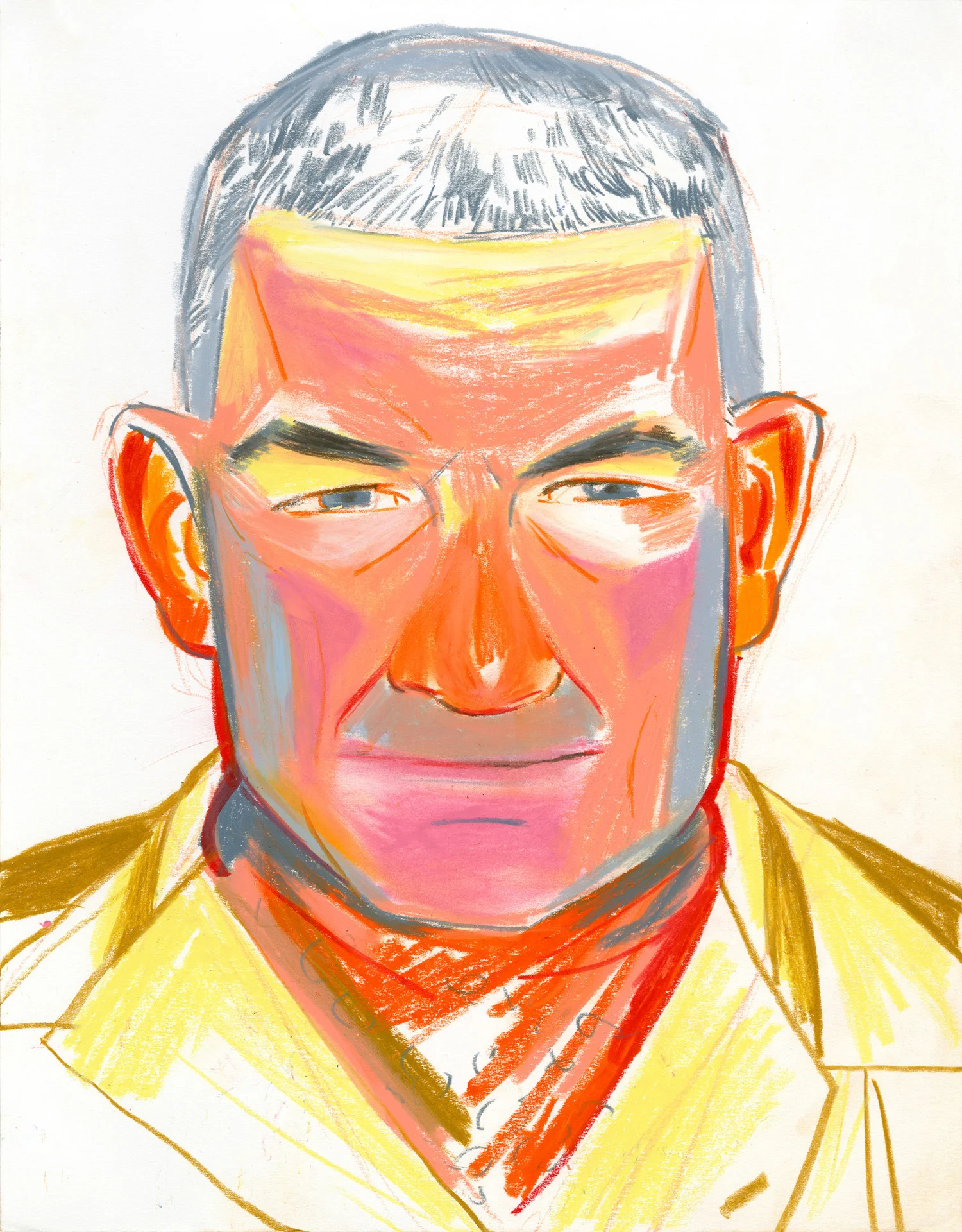

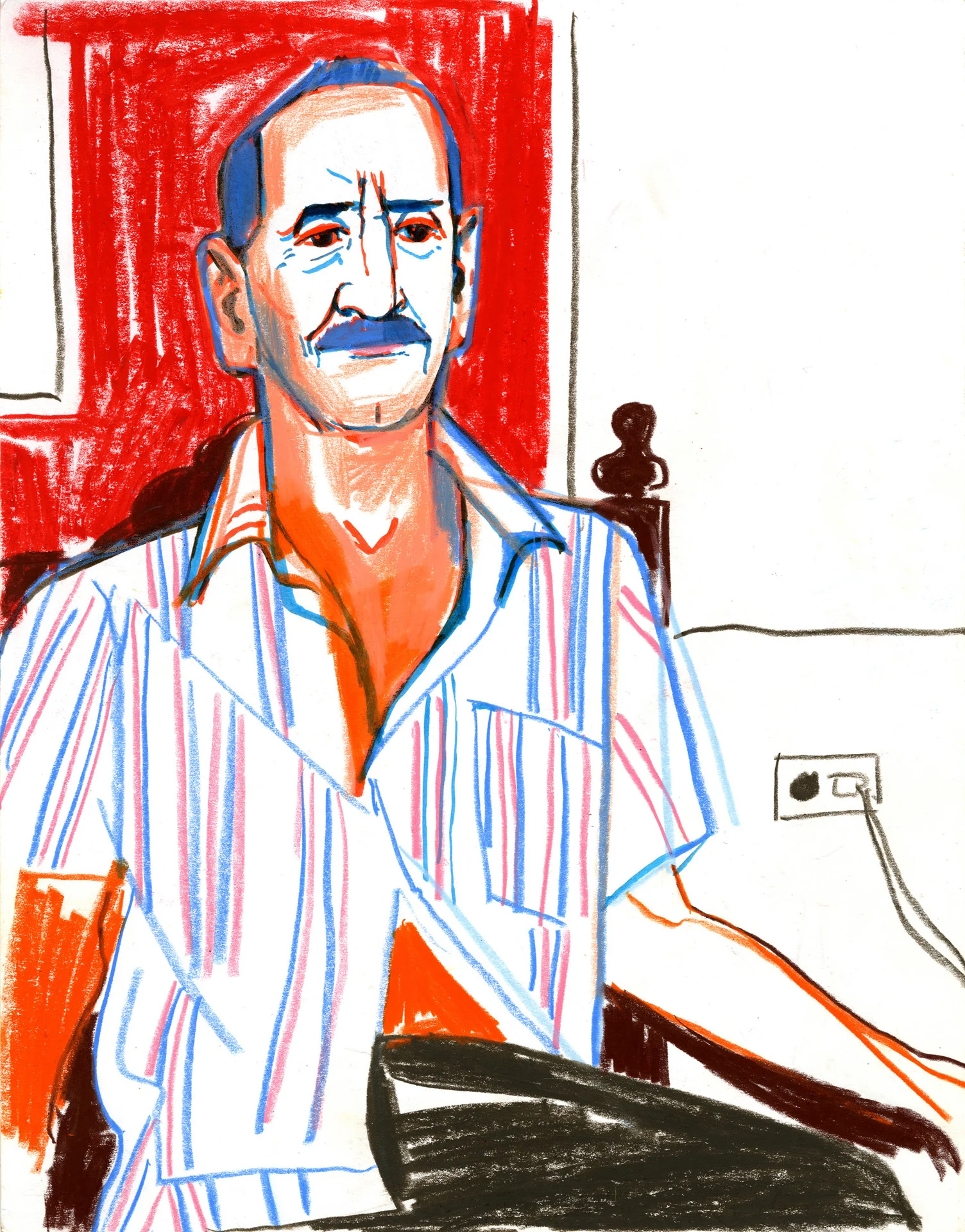

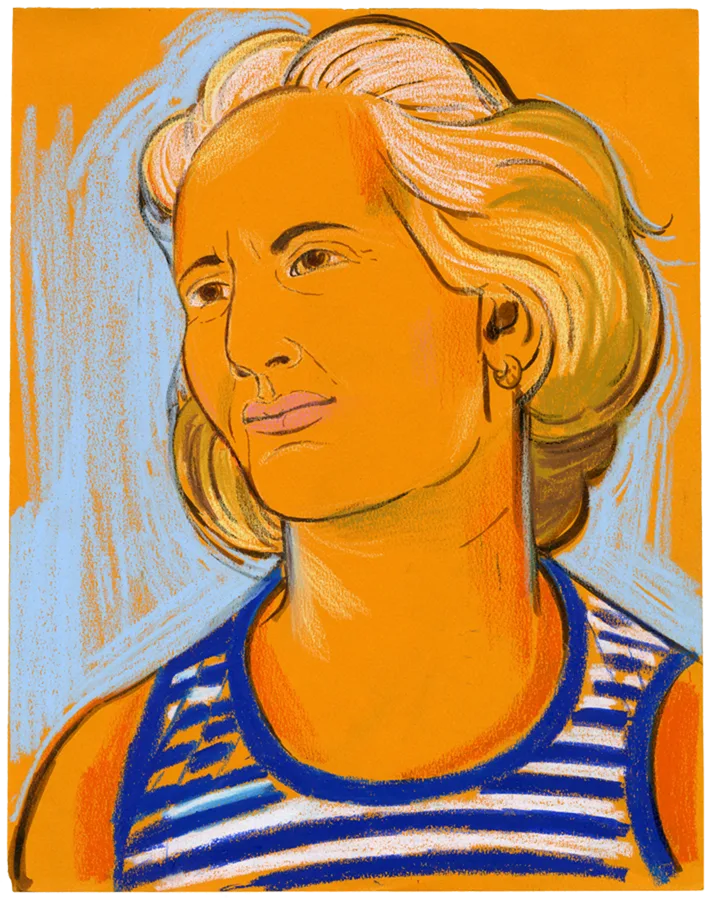

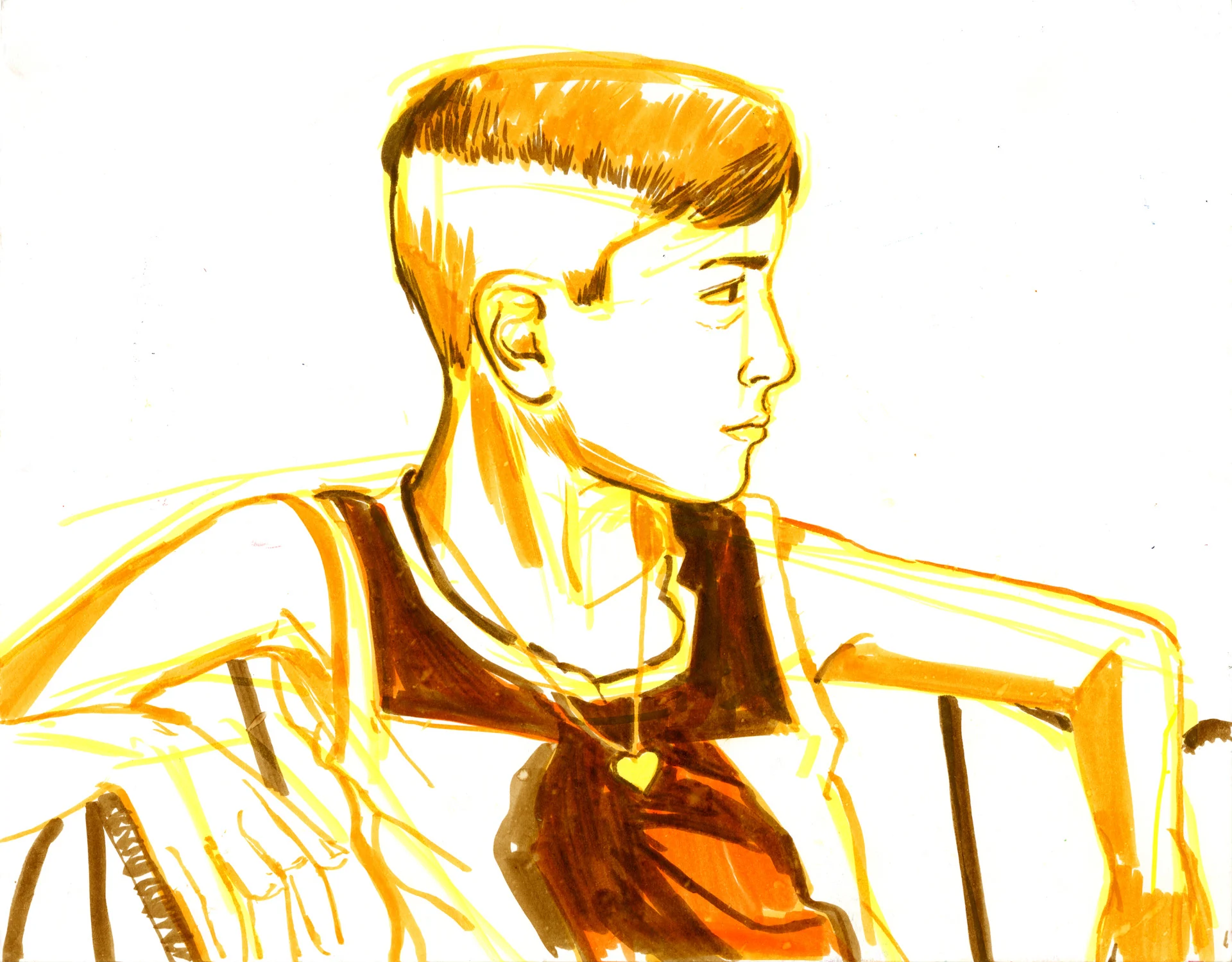

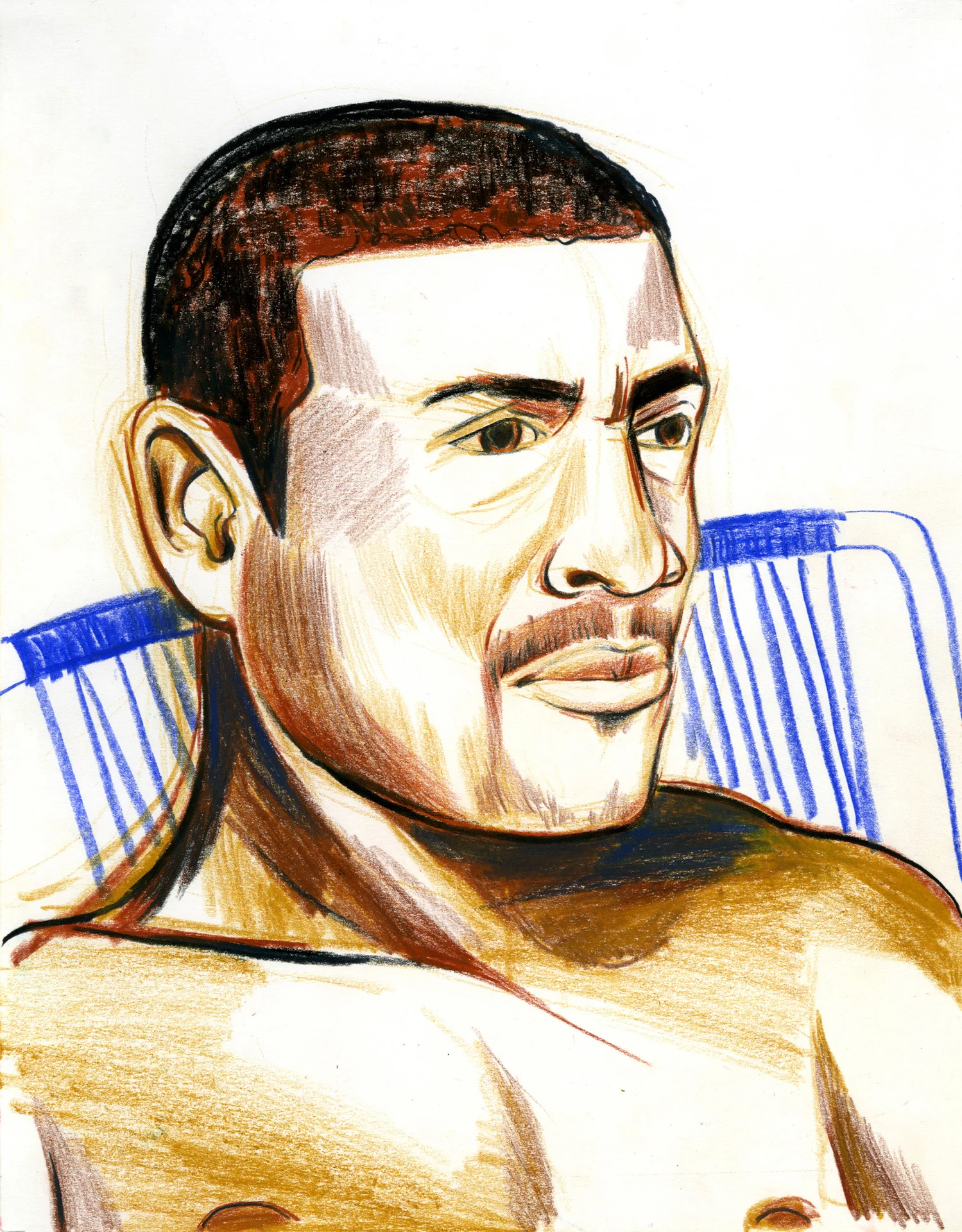

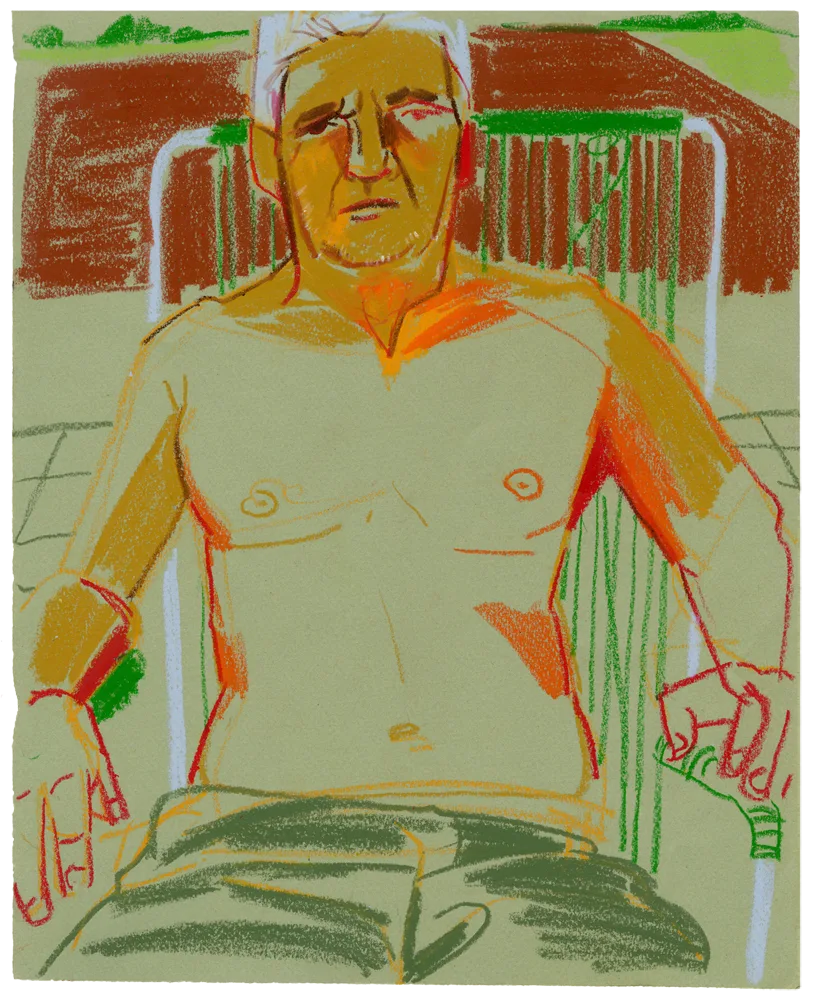

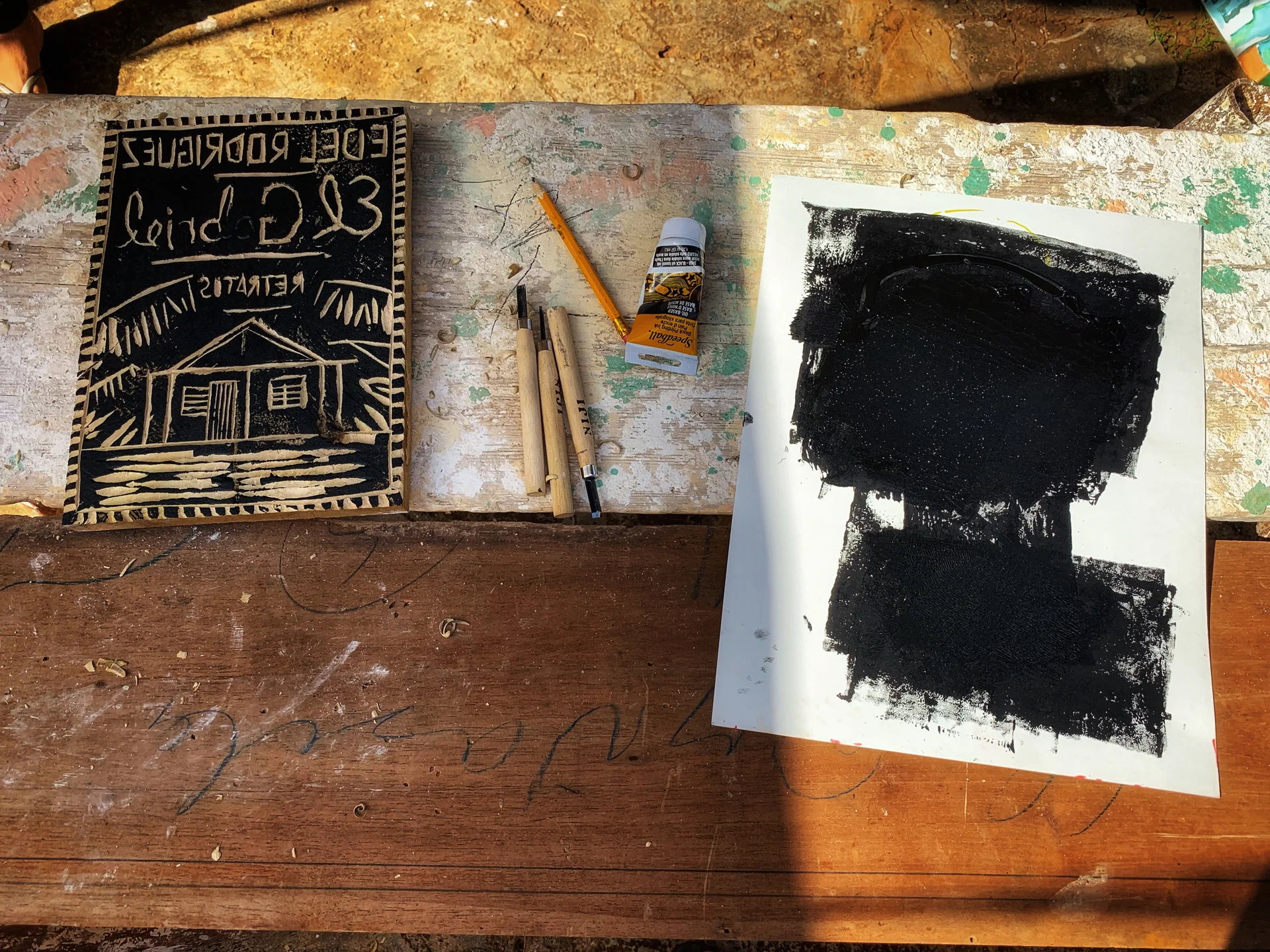

Edel, having come home to paint portraits of his townsmen, hoping to be able to give them something they’d never otherwise have, is surprised by the interest the project has garnered. He expected to have a few neighbors and friends to paint, but no excessive interest. He is instead faced with a steady barrage of requests, with sometimes two or three neighbors waiting their turn around the house in a formless line that feels more like a small party. It’s a pleasant, if unforeseen, development.

“I wanted to make these portraits and give them to people as a gift, as something special that they could hold onto and generally not something that small town Cuba gets,” Edel begins. “I always want to give these people in my hometown something, and this felt like the right kind of thing to do. I spend a lot of my life and my career making portraits of scoundrels, dictators, criminals — people who don’t deserve to have their portrait made,” he continues. “And I wanted to take a break from that to come here and paint people that deserve to be painted, because they’ve done so many things in their lives to help each other and their families. That’s important to me.”

What you learn quickly observing Edel in his hometown is that it is equally important to him to both have the opportunity to reconnect while, simultaneously, having the ability to put the excitement and inspiration that comes with seeing everyone — exchanging uniquely Cuban banter as his eyes scan bodies for colors and patterns — into art. And that balance is no easy feat to achieve amid family and food and friends, mosquitos, squealing pigs, street vendors and the sinisterly sedating sun, luring you into midday slumber.

When at last we make it next door to Nilda’s house she hurriedly ushers us out through the back. “Here we are, in the childhood playground,” she announces, knowing that Edel would receive it as an invitation to exhale.

In that moment Edel’s urgency to make it to that small, unassuming patio, and his insistence on returning to it every day as his makeshift studio became clear. The afternoon light flooded it with gold, casting down a dreamy glow. The yard alone had an imperceptible magic about it, all the more enchanted by its tangible elements: a large green birdcage housing eight Indigo Buntings — blue birds known to often migrate by night, using the stars to navigate — a former pig pen now painted fire-engine red and adorned with animal figurines — a triceratops, a laughing pig and a wax lion — and a variety of flowering plants. Trinkets hang along the walls — mixed messages, a pink mirror, Winnie the Pooh, Spiderman and another birdcage, only this one is small and pink. Bottles of Bacardi sit prominently on display despite the island being home to Havana Club Rum.

“This is why this place is so cool,” Edel says, pointing to a wall covered in oxidized tin. It was inscribed with an ode to Cristiano Ronaldo of Real Madrid, written in red paint. “Everywhere you look there’s something. How many times have I used that color in my work?”

Maybe it’s because he spent so much time here before leaving for the United States, or maybe it’s the memories that make it warm, but Edel has by now spent more time away from the childhood playground than he did in it, and still there are details here that can be found deeply ingrained in the themes of his work. They are details through which you can see his paintings come alive — details which make it seem as though either you’ve fallen through the canvas into a new wonderland, or the canvas has ruptured and bled out across the whole of the world surrounding you.

El Patio de la Infancia is as much a place as it is an illusion, a construction of reality all his own, a refuge amid the loving absurdity of El Gabriel, where the town jester found his voice only after having lost his voice to cancer, the children play baseball and make trouble in all the same ways they have for half a century, a local underground cake man bakes in an oven fashioned out of corroded sheet tin, the town market is actually called “The Illusion,” and the only official bakery is, accurately, “The Surprise.”

Moments into setting up the playground studio, Edel notes a fan that Nilda has turned on to blow away mosquitos. The fan, he remembers, is an old Russian model that’s no longer made, and it’s been in the family since the 1970s.

When his parents were preparing to flee as part of the Mariel exodus, they gave all of their belongings away to neighbors. It’s common practice in Cuba to gift or sell everything as the sign of impending flight. But when the military arrived with a list of items they knew the family to own, they demanded that every object be returned to the house and the house sealed, or they would not be granted permission to leave. This fan is the surviving artifact that was not confiscated — that was never returned to the house. Everything else — the car, the furniture — was taken into government custody. Nilda has kept it, in working condition, for 40 years. It is today a symbol, a piece of evidence, a monument of what once was and what today remains.

“I love this fan,” Edel says. “This is why I love it here. Everything is so real. There’s so much power in these objects. You don’t have air conditioning so you really feel the temperature. You hear the man screaming outside, selling wheat for shakes. The roosters wake you in the morning.”

Edel trails off into his thoughts about the dueling realities and festering paradoxes here — the freshly painted front of the house juxtaposed against the aging side of the house that could not be painted, the eternal sameness that is somehow always different — things that break, social halls that fall and are never fixed or rebuilt, but remain in their place to fade in plain view. The bakery that bakes only two kinds of government-issued, rationed bread, which on any given day cannot bake because the ingredients don’t arrive. The food shortages amid agricultural abundance — hundreds of mangoes fallen everywhere creating their own swamps and emitting their distinct rot — the black market, the two currencies. The caged Indigo Buntings in Nilda’s yard that are pets as much as they are allegory, each night when the blanket comes down over their enclosure, severing their senses from their navigational tether and any possibility for orientation. The stars go dark. The birds are in a state of fixed motion, persistently fluttering about without being able to go anywhere, and still they sing early every morning.

Here, people live an eternal return. Every morning waking up and setting out to find the thing that is needed, often committing the entire day to the task, often reaching no resolution, only to wake up the next day and do it again.

“People’s dignity is crushed here every day,” Edel explains. “Every day, with everything they have to do: having to find food, not being listened to, not being respected, being lied to — their dignity is crushed every day in one way or another. And I feel like this project at least is a drop in the bucket of giving them some dignity back.

“I don’t presume to think that I can do that completely for people,” he continues. “But I do think I can bring them some happiness.”

In many ways life here is about entrenchment and endurance—about the world beyond this world, imagination, resourcefulness — because this one is inescapable. But the notion that this should devastate the collective spirit of a people is not a consideration. There is exhaustion and hunger, but like the Buntings that sing in the morning, there is also good humor — sometimes crude and inappropriate — and that is as Cuban as pan con aceite y sal.

One morning in 1989 when Edel was 18 years old, he received a call around five o’clock in the morning. His uncle, the husband of his favorite aunt Nancy and father of his cousin Liset, had been run over by a train. It happened at a time when Edel and his family were barred from returning to the island, unable by politics and circumstance to make it back. That night, he remembers, he and his family held a wake in their Hialeah home, but it was without a body. There was a sense of familial and spiritual disconnect, a sense of metaphysical displacement, as he explains it, that they attempted to bridge with memories and jokes, but that only brought to the fore how old those remembrances were and how long the families had been apart.

“I spent 10 years without seeing my aunt and that was 10 years of lost time, lost life,” he says. “So when you ask, ‘what do immigrants give up?’ You give up 10 years without seeing your family, without seeing your favorite aunt. You give up entire memories. You give up life.”

In the throes of reflection, gazing into long simmering resentments, he reaches the real crux of why he came back to paint these portraits. He left at eight years old, an age, he says, when children are just beginning to sense what people around them are, who they are, and suddenly you are gone and they are gone, and you’re left to wonder—with more age and awareness—what might have come if you’d stayed. If you’d been able to carry the weight that life is unfolding.

“I wanted to show the face of the people from these countries and tell their stories,” Edels says. “To get across to an American audience the idea of who these people are. The stories of why they left, why we left, why my parents left, why some decided to stay behind. We’re always focused on what immigrants want. And we never focus on what immigrants leave behind. So I wanted to respond with what I left behind. To show that we’re not just in the US to take, we’re in the US to contribute and give to our families, and we’ve also sacrificed to be there. We’ve paid our due.”

“Recently it seems,” he continues, “you give up all of these things to go to a country and start a life, for a reason, or different reasons, and then you have people refusing you. Accusing us of just taking things that belong to Americans.”

For all that Edel has made public about his positions and politics, his personal story and that of his family, he remains a somewhat elusive figure at his core. He remains light on the exterior, at almost any cost, and it isn’t until this moment that a person sitting before him can really see him sit in his pain and keep himself company. So I put the pen down and let him speak. About the aging faces he left behind. The sense of abandonment and guilt. The loss of life and the determination to present that through art, in a way that might make strangers feel it too.

These are his stories and those of his loved ones, and so it is only right to end them with his words.

“As much as you’ve helped and stayed in touch throughout the years, you still have the sense that you’ve abandoned people because it’s just the circumstance. I didn’t have anything to do with leaving here and my father left for a better life but there were a lot of problems they dealt with that we weren’t around for. And it’s really weird to have your grandmother and grandfather die and you can’t get here. You can’t get here in three days or a week’s time.

Or two weeks or even three weeks. It wasn’t so easy. So you don’t have that closure, without burying your grandmother or your grandfather, without burying your uncle. You’re always left with these stories that don’t quite have an end. They don’t close out for you. And occasionally throughout the years I’ve put it into my work just as a way to think about it or to cope. And I don’t know if part of the reason I make art is also to avoid that sort of stuff. When I was writing my book, any time I started writing about my grandmother I would just break down. To feel that and then have someone go out of their way to write to you and say ‘shut up, just paint other things’ and ‘why don’t you appreciate America, what did you come here for, why are you criticizing the government…’ When you’ve gone through all that, it irks you. Meanwhile here you have all these souls that are leaving this place and eventually it’ll just be empty. There are spirits here that are just — “ he looks down and snaps his fingers, “gone, gone, gone, gone.”