In an age when borders are battled over and masculinity is more mixed-up than ever, cowboys make for compelling protagonists. Enter Cowpuncher My Ass, a dance show choreographed by Holly Blakey, with sound by Mica Levi and costumes by Andreas Kronthaler for Vivienne Westwood, which showed to a sold-out auditorium in London this February. Writer Maisie Skidmore and photographer Max Barnett went to watch.

We’re in a studio on an industrial estate in west London – the Wild West, if you will – where choreographer Holly Blakey and her crew of dancers have been rehearsing solidly for the past four weeks. In two days’ time Cowpuncher My Ass will open at the Southbank Centre, the first of two consecutive performances. (“The show’s not finished yet,” Holly tells me, later, thoughtful rather than concerned. “But I don't know if it will ever be finished.”)

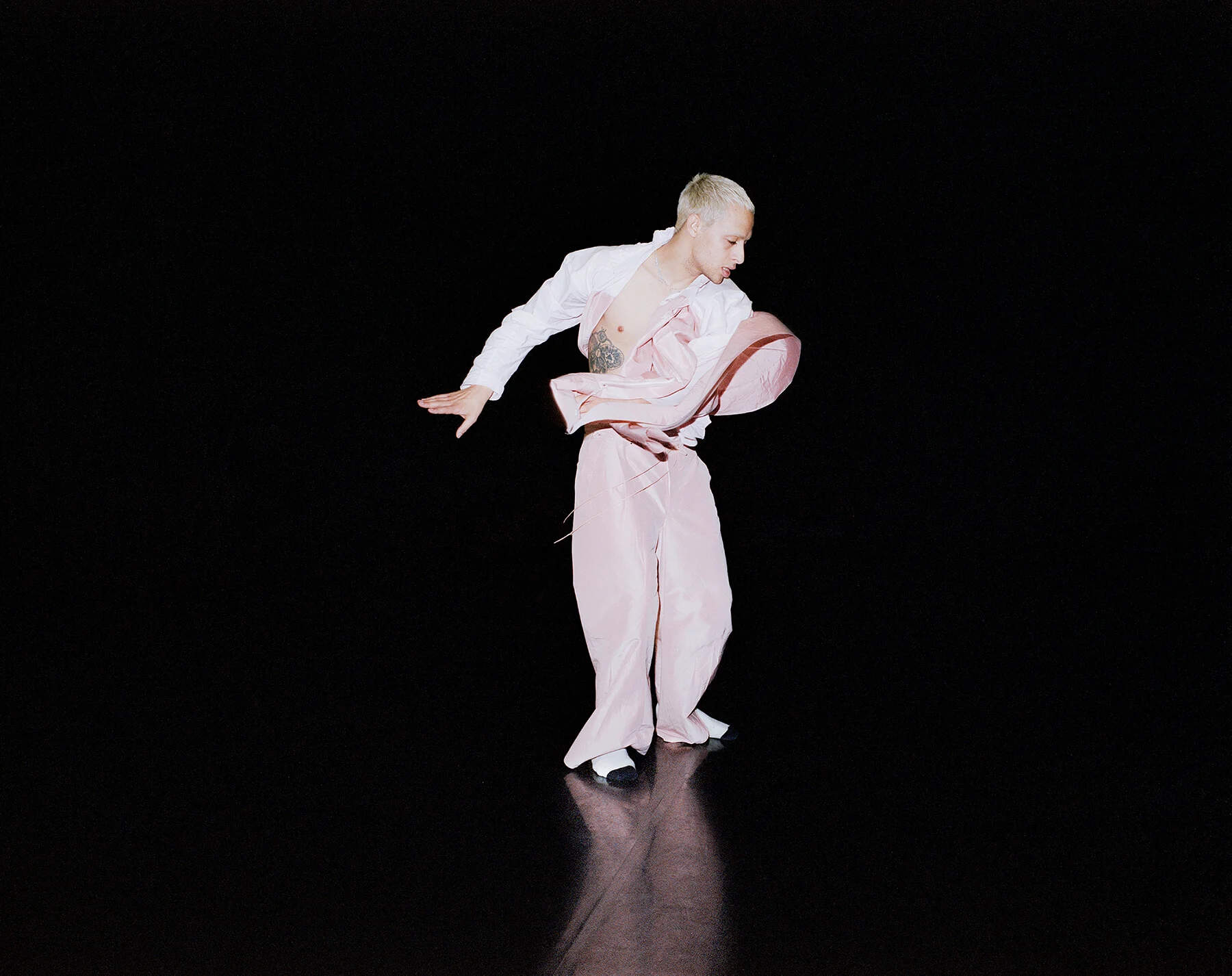

They’re almost two thirds of the way through a full-run, in costumes provided by Andreas Kronthaler for Vivienne Westwood, when the choreographer steps forward from her spot front-of-stage to pause the music. “Let’s stop it there,” she calls to the dancers. She wants to try something. “You two are gonna hate me,” Holly says, approaching dancers Sakeema Crook and Grace Jabbari, “but can you swap costumes?”

“God, I feel really angry after that,” another, Chester Hayes, says, shaking away a tear. He stopped in the middle of a supercharged sequence that feels something like a duel: brutal, heart-wrenching, compelling to watch. All seven of them step off the floor to drink water, eat crisps, stretch. Even when they’re not dancing they seem somehow to move together, reaching out playfully and tenderly to soothe and tease one another like they’re speaking a secret language.

People were talking about building walls and who owns what land. And I was like, aren’t we living in a fucking Western?

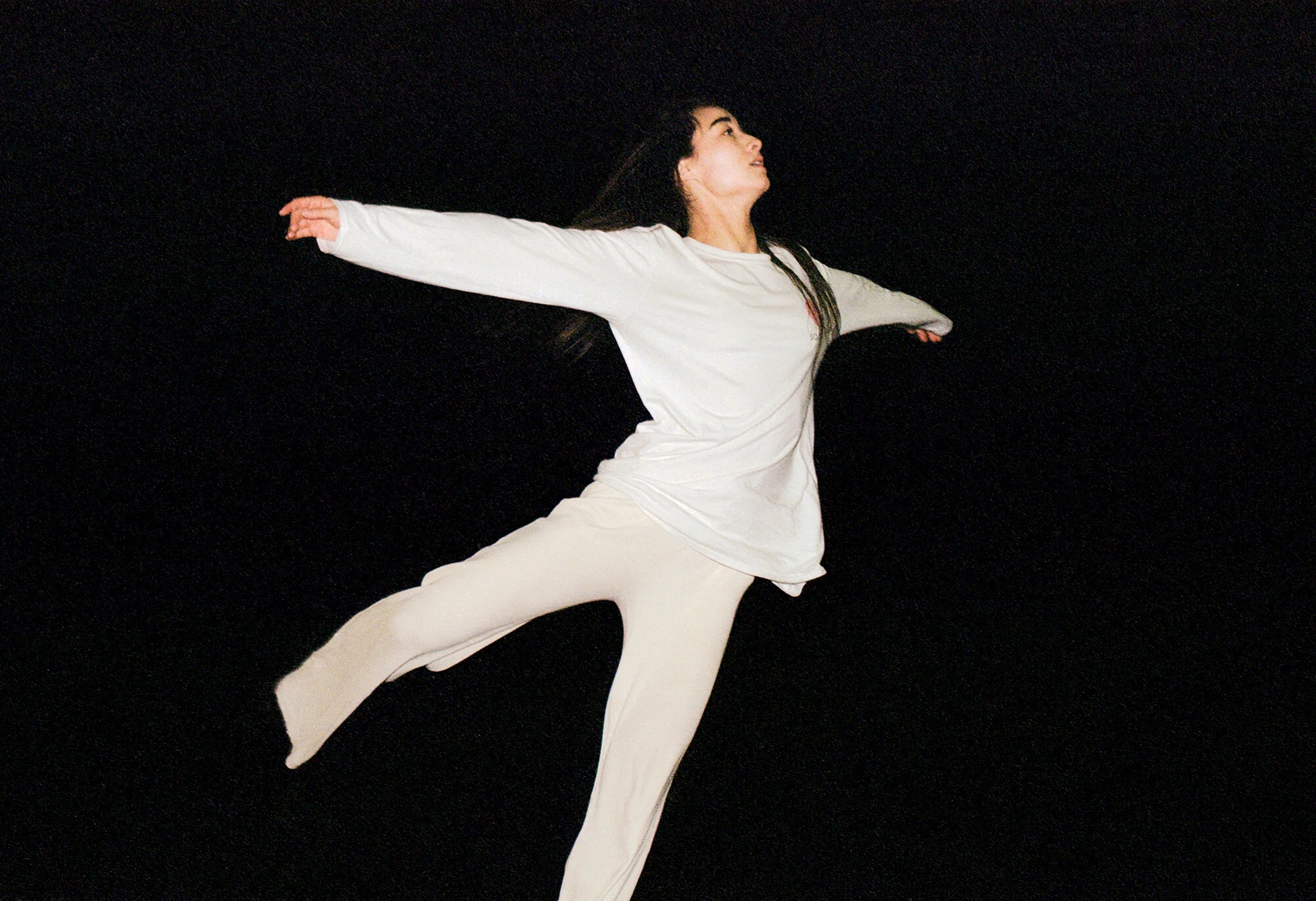

Cowpuncher My Ass is a Spaghetti Western of sorts, magnified and transposed to a contemporary stage. It is by turns agonizing, gorgeous, frenzied and sublime; it deals with identity, obsession, camaraderie, isolation, power and politics, all depicted by its own cast of outlaws. It’s also a sequel: the first show, Cowpuncher, originated in 2018, when Bengi Ünsal, the Head of Contemporary Music at Southbank Centre, commissioned Holly and composer and sound artist Mica Levi to create a new work, to reopen the Queen Elizabeth Hall. “We had two weeks to make the last show, from start to finish,” Holly tells me, in a break from rehearsing. “We wanted to make something bright and charming and fun, but when you scratch the surface of these themes, they're not, obviously. I felt like we’d started to dive into something; I wanted to do justice to the characters, to develop it and explore it more, and see if there was a deeper way to harness it.”

Then, as now, a Western seemed a natural fit, says Holly. It places the complex masculinity of the roguish cowboy center-stage, but it also “came at a time when Brexit was happening, Trump was happening. People were talking about borders and building walls and divides and who owns what land. And I was like, ‘Aren't we living in a fucking Western?’”

But the accessibility of the Western as a genre, elevated to the stage, also straddles the ideological divide between high and low – a thread which runs through everything Holly does. Born in North Yorkshire, she trained as a dancer before moving into choreography and directing, primarily through music videos; she has worked with Florence & the Machine, Coldplay and Gwilym Gold, but also the likes of Gucci, Dior and many others. This interrogation of high and low has continued to inform her artistic practice. “Because I come from a pop video heritage, I'm always struck by the way things that are made for mass culture hold less value,” she says. “High art is made for a much smaller group of people. I’m interested in what's available on a contemporary dance stage. What am I allowed to do here? What am I not allowed to? What if I want to do a pop video on this stage, how does that shift what I'm saying?”

In challenging the elitism of contemporary dance as an institution, she’s ready to estrange some audiences. “My work is divisive. Some people love it, a lot of people hate it. But I’d rather it not be polite.” Bengi, who commissioned both Cowpuncher and Cowpuncher My Ass, relishes the role that the Southbank Centre can play in democratizing the stage. “There are a lot of young people, choreographers and electronic musicians, doing amazing work at the moment. I wanted Southbank Centre to be a place that showcases that to all kinds of audiences. We're for everybody.”

Some people love it, a lot of people hate it. But I’d rather it not be polite.

Back in the studio, the music is on again. The sound, too, is a powerful rumination on what a Western can be. “It is wild!” says Holly. “You can hear Mica all over it.” Glasses of water tremble with the bass. “There are lots of motorways, and vibrant, natural sounds. Then it's heavy and dark, and there's a sugary, charming, sweet section. So it goes on a journey. But it's very, very, very powerful. We've decided to give everyone earplugs as they come in; we want you to feel it in your body.”

On my right, lighting designer Edward Saunders is putting finishing touches to his plans. He has been in and out of rehearsals for weeks, absorbing the energy of the dancers in order to correctly respond to them. “It's about trying to to understand the tension, so that you're coming from the same place,” he explains. “The lights are a component that you can't actually see until you get into the space, so having that shared vocabulary is essential.”

How we read one another and love one another – it’s always with the body.

A vocabulary, of both language and movement, is crucial to Cowpuncher My Ass. Sharing thoughts, feelings and experiences plays a central part in building the show, Holly explains – especially in a piece which relies so heavily on its characters. “I choreograph it, but their journey and emotional process is something I ask for them to search for. We discuss it and talk about it a lot.” It’s almost a more traditional approach, to create a cast of characters in this way, but with such varied dancers it feels resolutely contemporary. “They're from different choreographic backgrounds, they have very different bodies, they have very different energies,” Holly says. “They're not a corps de ballet, they're not uniform, they don't do everything the same way. So instantly, this sense of individuality is thrust upon you. It's from there that we start to think about what character might be, but also who they are, and their agency.

“And then you're confronted with other difficult things, like responsibility,” Holly continues. She is constantly considering her own, as a choreographer. “I want to talk about difficult things. Am I allowed to ask you to share these things with me, about your masculinity, about your sexuality? Can you perform that vulnerability? We had many difficult moments, in the process. There are always a few days when everyone's hysterically crying.”

For the dancers, working like this is exquisitely freeing. "We're all really different, and Holly pulls different things out of each of us,” says Tylor Deyn. Just as identity is a moving, changing thing in life, so it is for each of them on stage. “There's an overall feeling for each character, but we grow and shrink away from facets of ourselves,” says Sakeema. “We all have the capacity to be cruel, or gentle, or tender, with each other. It's about which levels are turned up at which points.” “I love that about Holly's work,” adds Chester. “That everyone understands what they see in a completely different way. We make our own narrative.”

Although the show has been meticulously built out of a collection of stories, interactions and emotions, there’s no single arc for the viewer to latch onto. Instead, it is deliberately subjective. “I use this idea of narrative, but not so explicitly,” says Holly. “I think it's very personal, and I think it will feel different to different people. You know when you read a brilliant book, and you're sure it's written for you? And everyone associates with it differently – I want it to feel like that.”

For dancer Grace, this refusal to spoon-feed the audience a narrative is part of the power of the show: “There's so much context and information – or not – on purpose. A lot of decisions have been made, but sometimes if it feels like we're giving them too much, we’ll say, ‘actually, let's mash this up.’ It's disjointed but in a really satisfying way, as a performer. We have the freedom to explore our own narrative, within a world that is created.” Through movement, this cast of dancers generously invites the audience to experience their own experiences, vicariously. “In an experiential sense, I think our understanding is better articulated through our bodies,” Holly says. “How we read one another and love one another – it's always with the body, isn't it? When you watch people moving, maybe you feel it too.”

All these things we make and do and watch, they’re only referencing life. Life is the thing!

Two days later, on opening night, there’s not an empty seat in the Southbank Centre’s Queen Elizabeth Hall. Sakeema and Grace’s costumes have been reversed back. There have been a few final tweaks to the sound. In a last-minute lighting change made in a final tech rehearsal, the house lights remain on until halfway through the show. The effect is to reverse the gaze; the dancers stare back at you, the viewer, making you feel complicit. It's unnerving and eerily effective. Then, just as you have started to get used to it, complete darkness falls, blanketing you with anonymity and that thunderous bass. You feel it in your body, and it feels divine. Somehow, emotion seems to fill the gargantuan space.

It’s slick and louche, then dainty, then merciless. The tension heaves, and then shatters. I’m struck by how familiar these intimate frictions feel – like tiny fragments of difficult day-to-day encounters, magnified and then played out in real time.

“All these things we make and do and watch, they’re only referencing life,” Holly said in rehearsal, a few days earlier. “Life is the thing!”