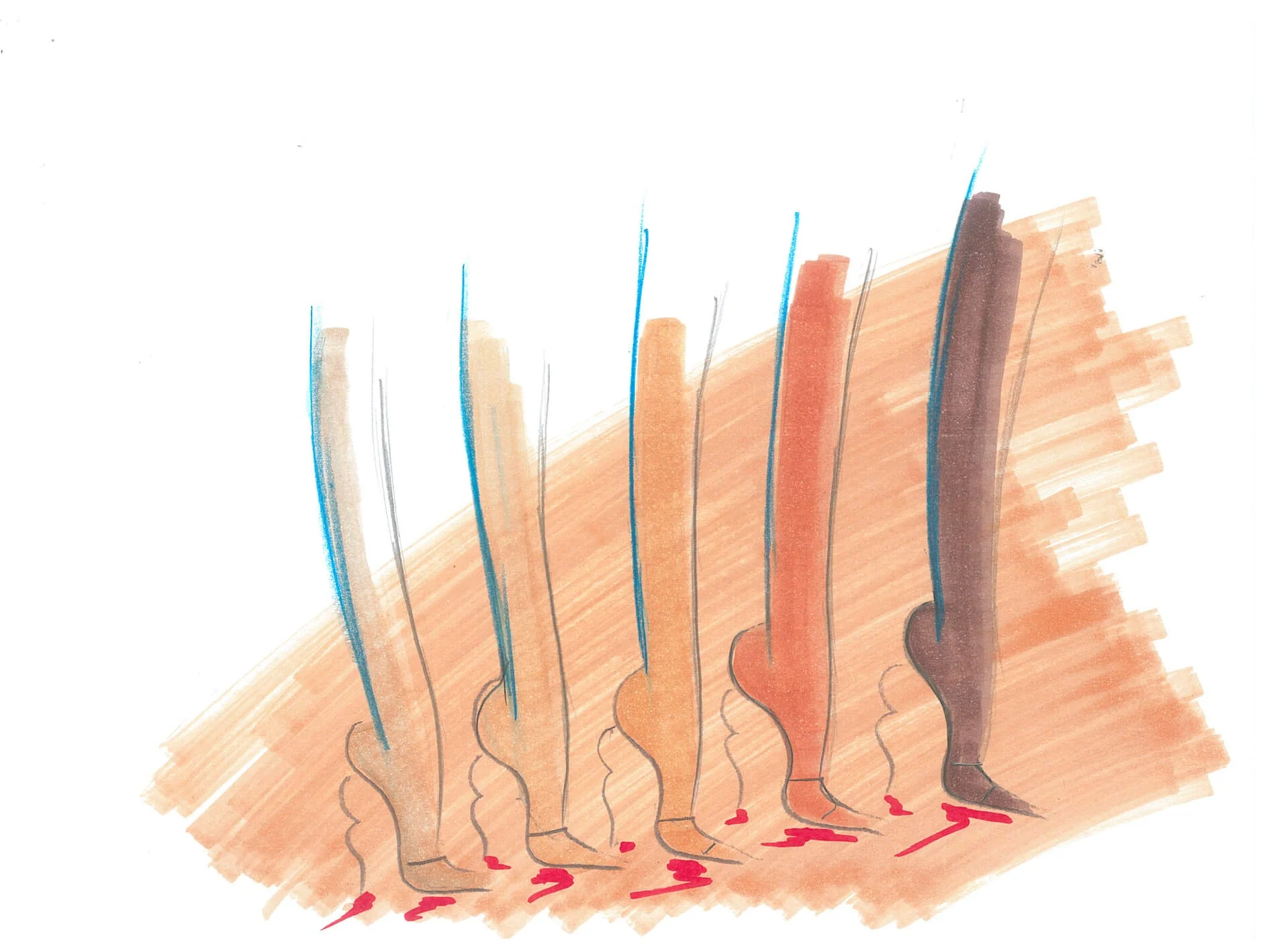

With a career spanning 30 years Christian Louboutin is one of the most acclaimed shoe designers in the world. From collaborating with designers to being immortalized in pop culture his famed “red bottoms” have achieved fashion icon status in their own right. This year an extensive exhibition celebrating his work has opened in the museum in Paris that first inspired his creativity as a child. Writer Holly Fraser sits down with Christian Louboutin to discuss his eclectic design process and unpick his vast collection of references.

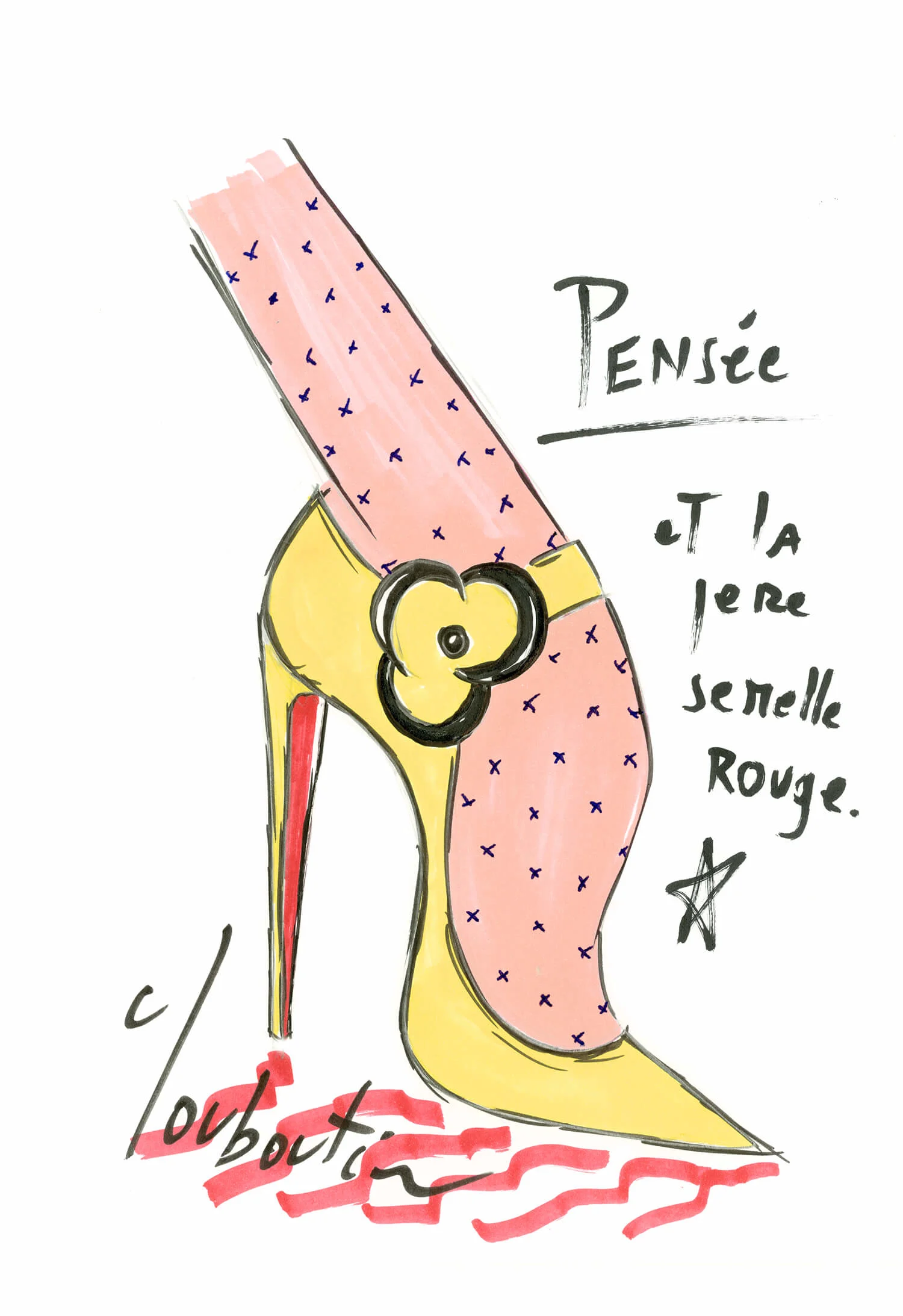

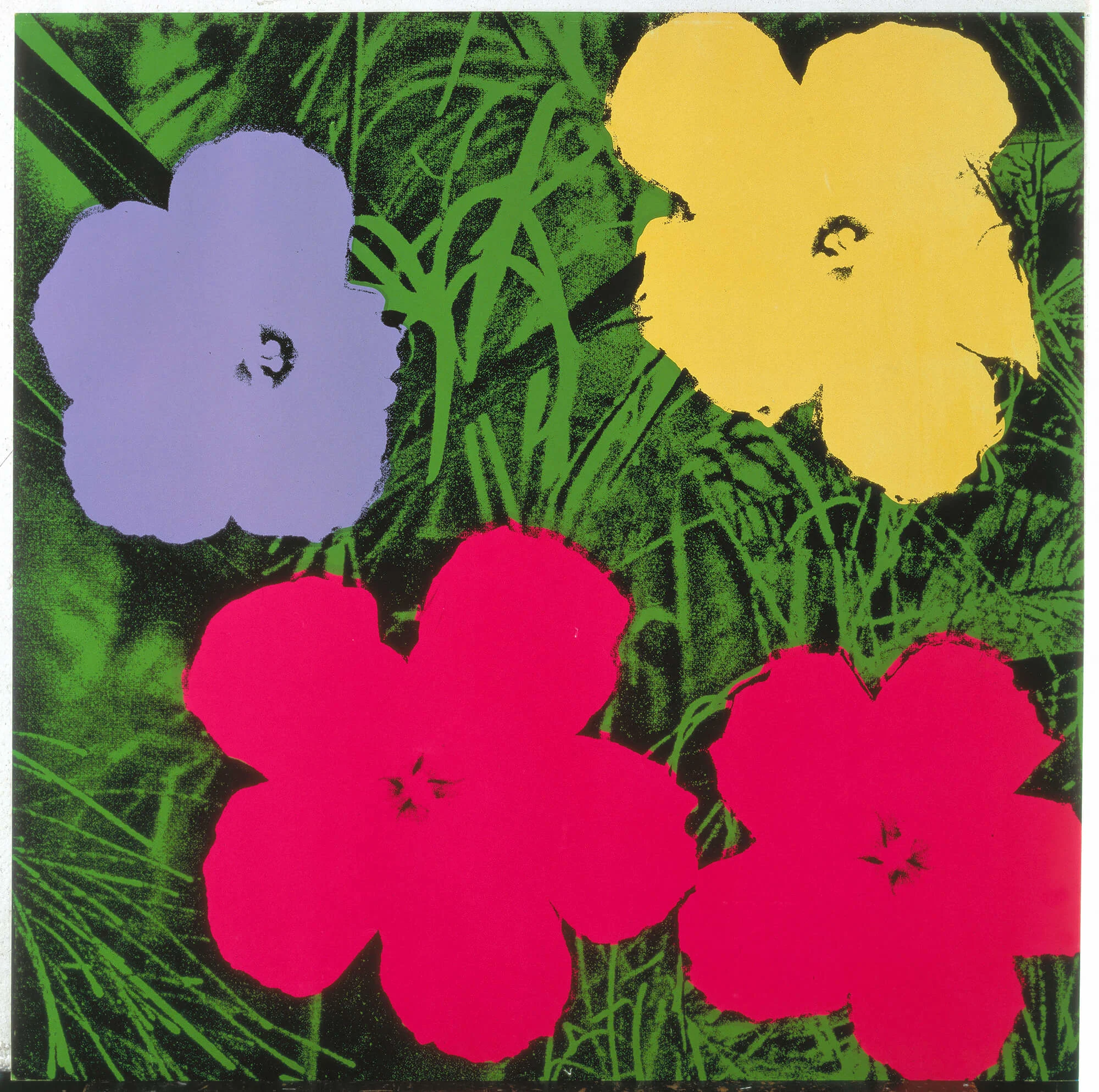

In the mid 1970s a young Christian Louboutin was struck by a moment that some might call fate. One weekend, while wandering through the Palais De La Porte Doreé museum close to his home in Paris, Christian saw his first ever drawing of a shoe. It wasn’t, however, in a grand exhibition or framed on the wall but instead was a simple sign: a profile of a spiked stiletto with a red cross through it, warning visitors that high heels were not allowed on the wooden floors. Rudimentary as it may have been, the image stayed with him and began the now world-famous designer’s love affair with shoes.

“That was my first wow moment,” Christian remembers. “When I saw it I was mesmerized, not by the beauty of it, but because it was a sketch that I couldn’t understand. It referenced a shoe that didn’t exist to me and was referred to as forbidden. To forbid something that doesn’t exist seemed strange and that really made me think.” That image played on Christian’s mind and a few weeks later would make itself known to him again, but this time with a Hitchcock twist. While watching television in his parent’s house Christian was flicking through the channels only to be struck again by a stiletto – this time on Kim Novak in Vertigo. “In one scene she’s wearing a blue tailored outfit and a matching pair of pumps in the same color,” he says. “Seeing those shoes on Kim Novak was the first time I’d seen the drawing become real.”

When I look at something I see the shoe, I extract the tiny details from what I’m looking at that goes into that shoe.

Christian would visit the site of that drawing many more times throughout his childhood, and, as serendipity would have it, our interview today is taking place mere feet from where he first saw that sketch all those years ago. In a nod to the place that sparked his childhood fascination, the Palais De La Porte Doreé currently houses L’Exhibition, the biggest ever exhibition focussing on Christian’s work to date. Walking through the exhibition it’s easy to see why the Art Deco museum was such a playground for an imaginative child — the foyer is taken up by a huge sweeping staircase, there’s an aquarium of tropical fish in the basement and the exterior is covered in carvings of people, ships, raging bulls, fruit, flowers and horses in battle. Throughout his years as a designer Christian has drawn on memories of the museum and the work within it as starting points for numerous collections.

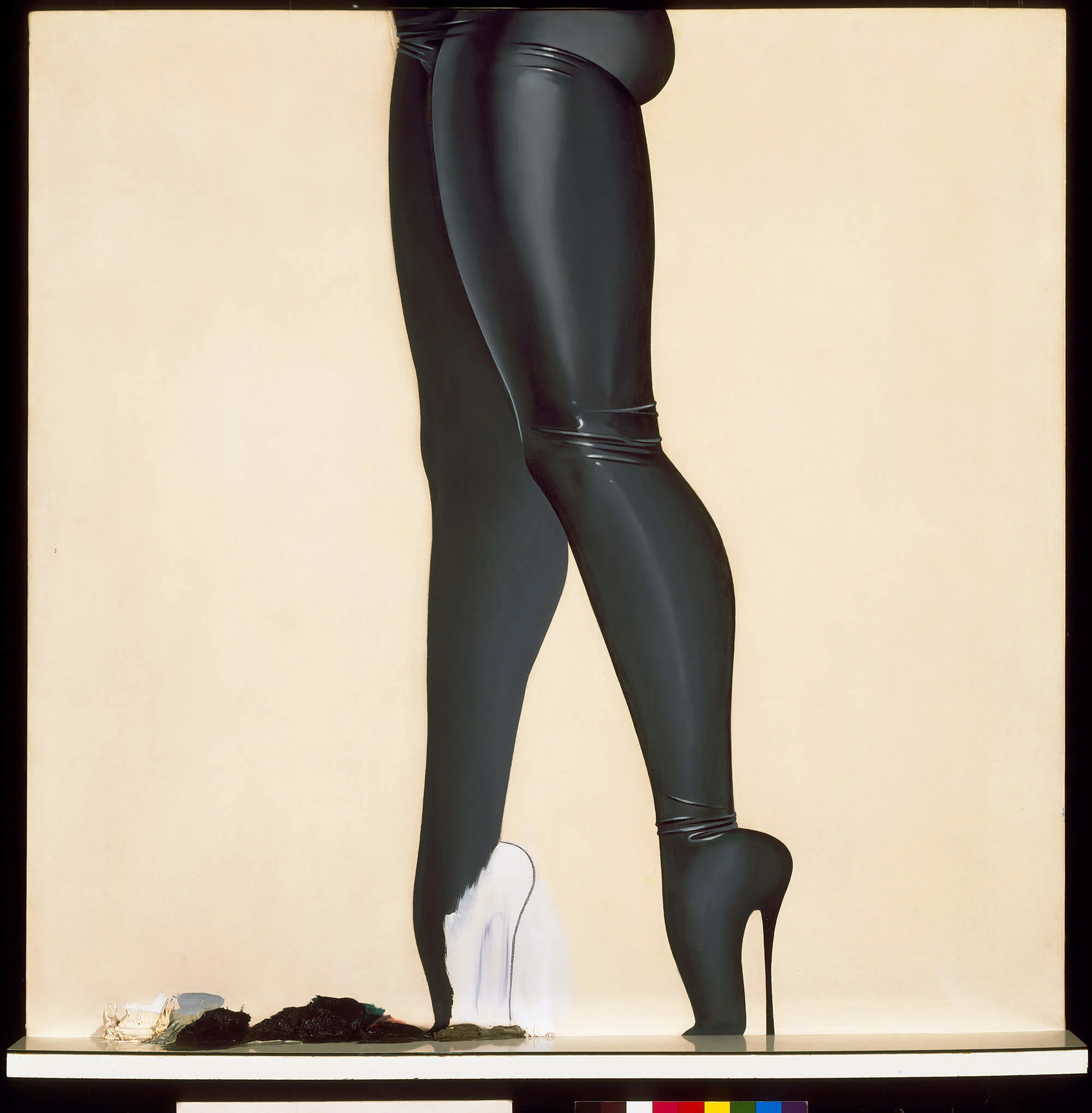

And in that time the red bottomed shoes that Christian Louboutin designs have become an empire. Synonymous with glamour, sex and style he’s created shoes for pretty much every fashion designer going during his 30 year career, but his work has also punctuated pop culture in a way that perhaps no other shoe designer has. The red soles of his shoes are a status symbol unto themselves, gracing countless magazine covers, being immortalised in hip-hop in Cardi B’s debut single Bodak Yellow as “red bottoms, bloody shoes” and exalted by Jennifer Lopez in 2009’s Louboutins. He has collaborated on a fetish collection with David Lynch and even ‘90s shoe queen Carrie Bradshaw ditched her beloved Manolos in favor of Louboutins by the time the Sex and the City movie was released in 2008. They’re the stuff of fashion legend.

Today, sitting against a softly-lit red wall and wearing an impeccable navy check suit and smart (Christian Louboutin, obviously) shoes, the designer is reflecting on what has brought him to this point. He’s charming and smiles when he speaks, starting most sentences with “alors” and ending them with “et voila” in his smooth French accent. Designing his first shoe at 23 he’s now 57, and his passion for his craft shows no signs of waning. He speaks with as much vigor about a small sculpture of a poodle made entirely from tiny shells as he does a jewel encrusted platform created for Elton John. Christian sees the possibility in the everyday, and this, it seems, is his secret ingredient. He sees creativity where others don’t. “You know in the comic Asterix and Obelix, when every time Obelix sees an animal he sees it roasted?” he says. “When I look at something I see the shoe, I extract the tiny details from what I’m looking at that goes into that shoe.”

What perhaps sets Christian apart from other shoe designers too is the intricate, and often very eclectic, references that form the basis of his design process. The first shoe he designed in 1987 was based on fish scales from his visits to the museum’s aquarium. The slingback pump was even decorated with an actual fish tail. “When it was finished I hid it in my jacket, brought it back to the museum and photographed it in front of the fish tank,” he says. “Now, 33 years later that shoe is back in the same place where I had once snuck it in.”

While the fish was first on Christian’s mood board, he quickly turned his attention to the entertainment world for continued points of reference. A child of the legendary Le Palace nightclub, Paris’ nightlife and bustling culture opened Christian’s eyes to new ways of designing. “There was the circus, music, film, literature, cabaret,” he says. “But in another sense it was the fluidity of that world. I like curves as opposed to straight lines. From architecture to art to belly dancing, I’m drawn to curves. I’m not like a Mondrian,” he laughs. “If I had to choose only five paintings to look at again, I would not take one of his.”

Christian’s need for constant references has led to an extensive archive of collected objects, some of which are on display as part of the exhibition in an area titled the “Imaginary Museum;” A celebration of his eclectic tastes, the collection nods to all of the cultures and genres that have influenced the designer throughout his career. There’s the aforementioned shell poodle, a bust of a fictional king by set designer Janine Janet, a sculpture from Damien Hirst’s exhibition Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable, Mae West’s shoe, gemstones, a small feathered bird and a Helmut Newton nude. But despite this miscellany of treasures and trinkets, Christian does not consider himself a collector.

From architecture to art to belly dancing, I’m drawn to curves.

“If you consider yourself a collector it means that you are building a collection, and sometimes that involves sacrifice – you might sell something in order to get a better piece – but that’s not me,” he says. “I’m just attached to objects; if I see something that inspires me I just have to have it. I still have regrets over things I missed out on.”

“There are some objects that just make me want to know more,” he continues. “But they also have to bring out my childish side, to make my eyes sparkle.” One such twinkling piece is a brilliant bright yellow floor-length feathered cape originally owned by 1930s film star Marlene Dietrich. Still in pristine condition, it wouldn’t look out of place on the Met Gala red carpet, but it’s not just its beauty but also its story that grabbed Christian. “Objects have to have a history that I can connect to,” he says. “I have seen photographs of that cape but they’re all in black and white. When you think of Marlene you think of monochrome glamour, but when you see this bright yellow feathered cape it is totally not what you expect. But Marlene was a very surprising person. She loved colors. Black and white films evoke a nostalgia and make you think in shades of gray, but the reality was much more colorful. And I love that juxtaposition.”

![Musée imaginaire, Exhibition view CL L’Exhibition[niste], photo by Marc Domage](https://images.ctfassets.net/adaoj5ok2j3t/3IWAk2Ry668l6QwAb1vP4I/0f27cde2b80c3f0ca4cd2926738ea692/Muse_e_imaginaire__Exhibition_view_CL_L_Exhibition_niste___PPD___Marc_Domage__4_.jpg?fm=webp&w=3000&q=75)

You can create delicate, beautiful designs but still be engaged with issues affecting the rest of the world.

While the flamboyance of a film star’s feathered cape might seem a natural fit for a designer working in fashion, other references in Christian’s collection have a more layered, complex significance that hint at what matters to him as a person, as well as a designer. One such piece is a recreation of a Wedgwood “Slave Medallion” from the Victoria and Albert Museum that Christian requested as part of the exhibit. Pictured on the medallion is a slave kneeling under the words “Am I not a Man and a Brother”. Christian notes that while the Wedgwood family were known in the 18th Century for creating beautiful objects they were also one of the the families in England most actively pushing for the abolition of slavery. The Slave Medallion was crafted in 1787 after Josiah Wedgwood became a leading member of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. They were distributed and worn by those campaigning against slavery and became one of the first instances of a fashion item being symbolic with supporting a cause.

“What I was trying to express by showing that was that you can create delicate, beautiful designs but still be engaged with issues affecting the rest of the world,” Christian says. “I think there is a preconceived idea that if you like decoration, fashion and jewellery then you don’t care about other people, but I disagree with that and the proof is in that medallion from 1787. To me, that says a lot. You have to be sensitive to be an artist.”