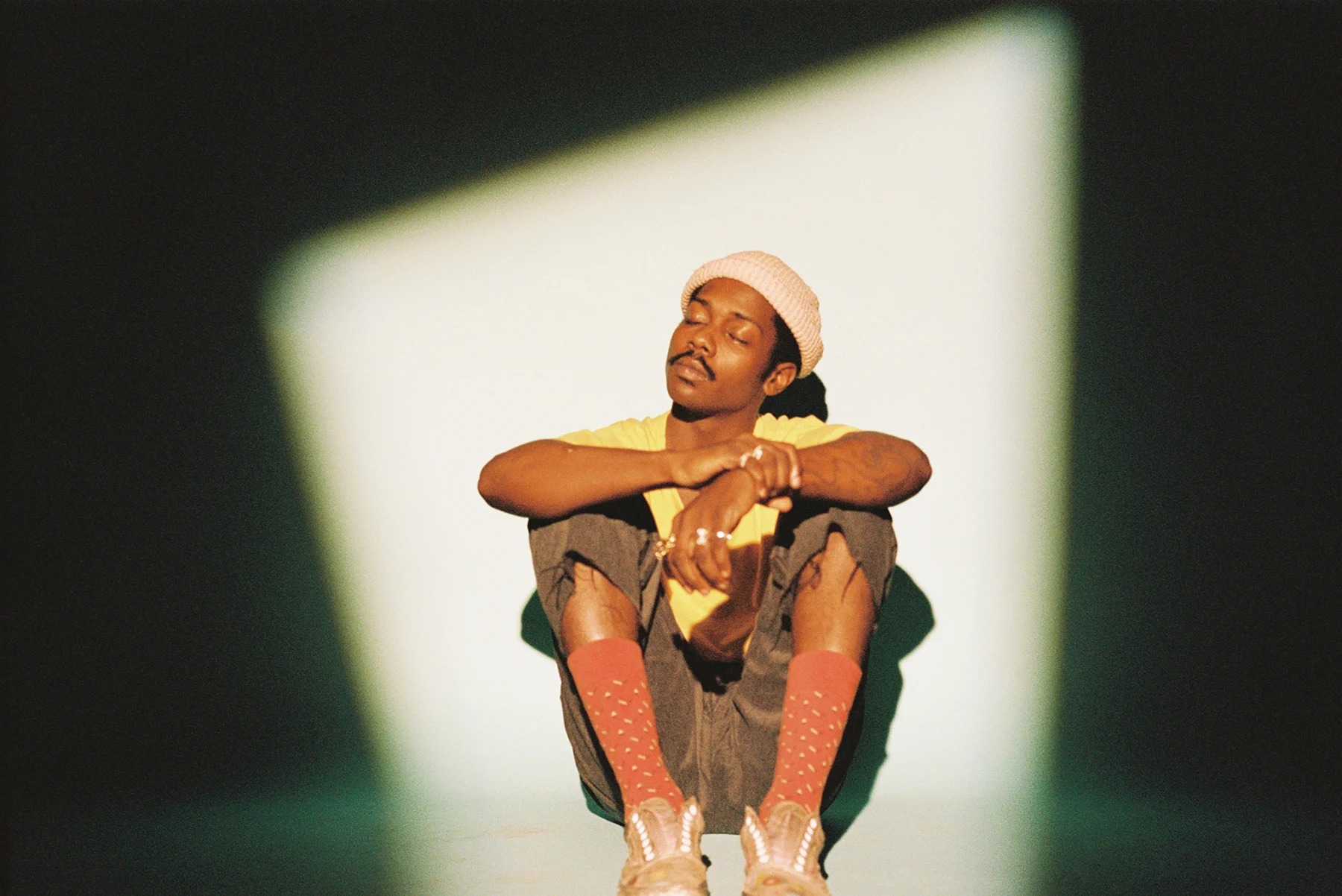

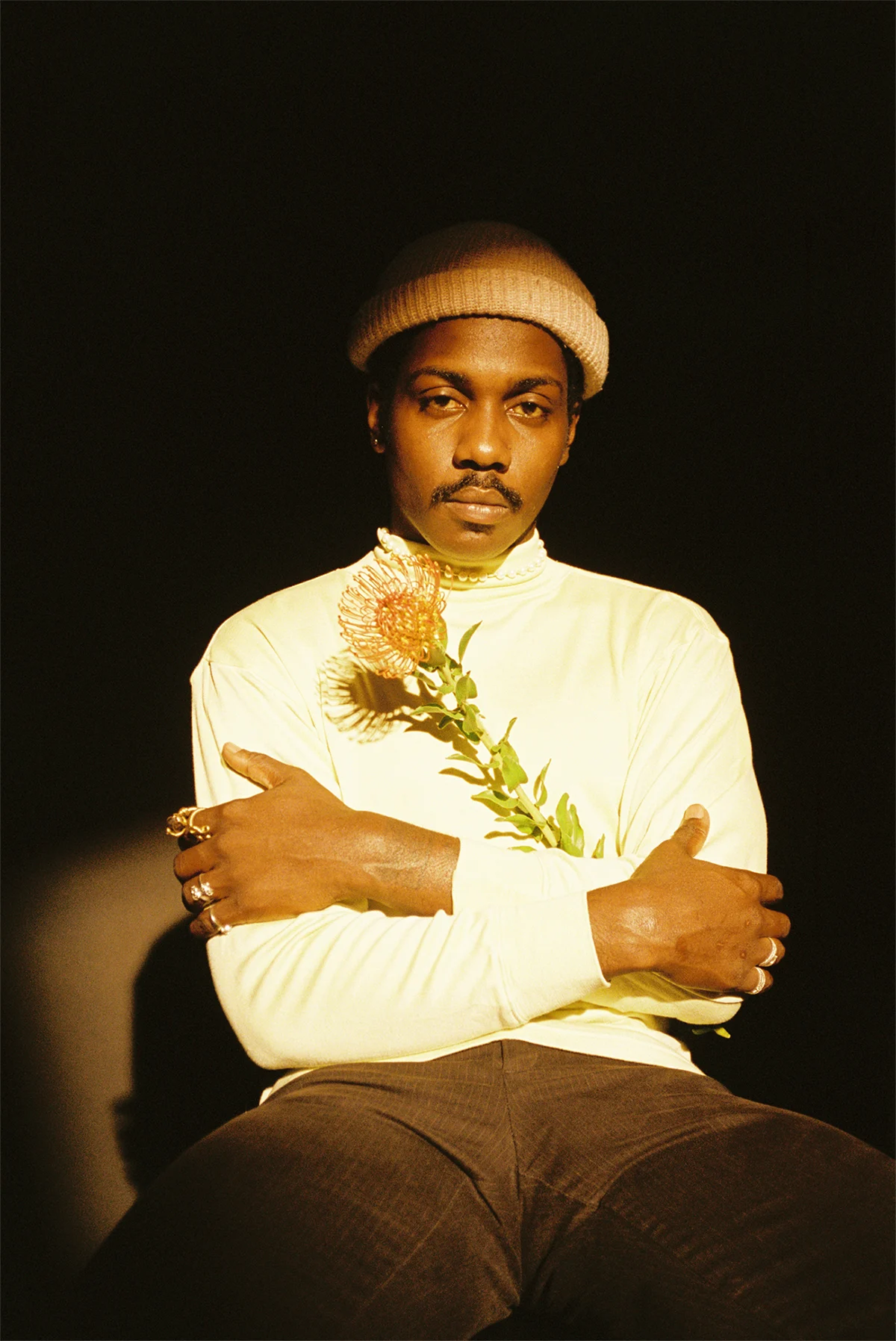

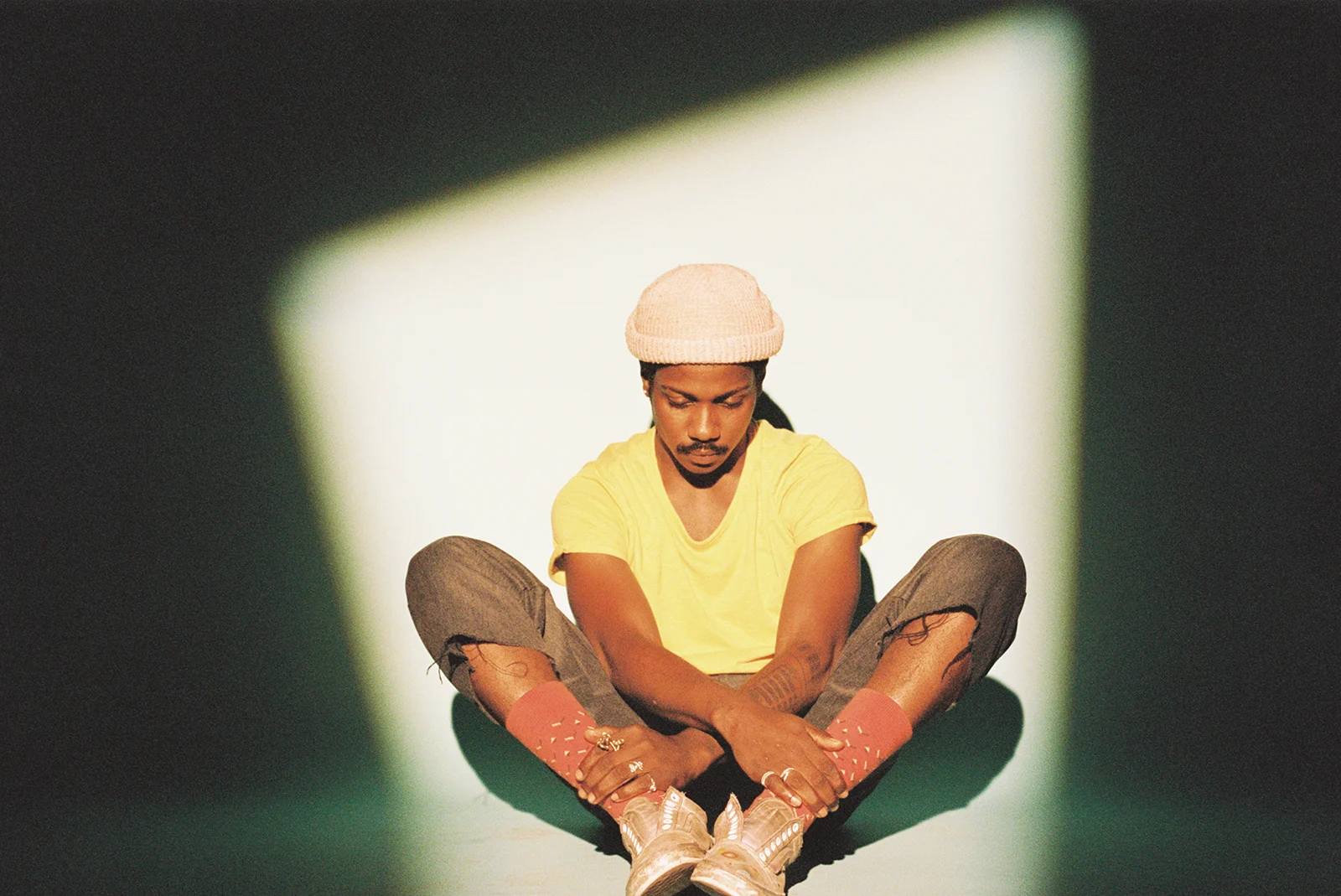

Channel Tres is reminding us to dance for the good of our souls. The charismatic, magnetic LA artist has dodged a career in social work (and, it turns out, one in EDM) to carve out a niche for himself in the dance genre. His old-soul wisdom sits comfortably alongside his cheeky, carefree sense of style, delivering important new sounds that are the musical equivalent to a grin across the room at a party. Writer Kieran Yates speaks to him over Skype as he slurps a strawberry milkshake and tells her about the road that led him to being the sparkling, in-demand collaborator and “LA’s new dance king” he is today.

“We started dancing because we didn't want to gang bang”, says Channel Tres nonchalantly of his teen years. “You had crews with rappers and beatmakers doing poppin’ parties in Compton, Long Beach, Paramount. That's when everybody was making dance videos.” Tres is talking to me from his bedroom in east LA’s Highland Park, around 20 miles from where he grew up, via the square grid of Skype, the new aesthetic of pandemic communication.

We speak just as a campaign around his new single and an upcoming tour have been cut short as the music industry looks for creative solutions to a period of uncertainty. Thankfully, he has a body of work to sink into, and the lifeblood offered by his Truants mix back in February has been balm for fans who continue to share it. Listening to it now, it feels like it was created specifically to take us out of the hopelessness of the moment and a brief look at the comments say it all: “you might be the goat, man,” “dope dope dope,” “pure magic.” It makes sense that his music is celebrated by artists like Kindness, Robyn, Childish Gambino and Vince Staples, having recently toured with the latter three, and he counts James Blake, and Tyler the Creator as peers and collaborators (notably, the only time Tyler has allowed an official remix, of Earfquake).

Today, framed by the Skype window, he looks like a still from a music video, and in an avocado green bucket hat covering short braids, a thin moustache, and a ‘90s ying and yang choker, he’s dismantling the idea of a one-dimensional Compton, too often depicted purely as a gang stronghold or site of trauma. In reality, his formative years, he says, offered him little parental supervision, an abundance of barbecues, (“You know that mac and cheese that just melt in your mouth?”) and a lot of dancing. His coming of age, he explains, happened just as Jerk culture bubbled on the underground of LA in the late 2000s. The genre, originally identified by gang culture, evolved and was located in house parties and halls. In a pre-Tik Tok dance video era, jubilant choreographed dance movements like the “reject,” “dip,” and “pin drop,” were being created, to tracks by artists like YC, Audiopush and New Boyz. While it may have originated with gang members, the culture transcended them and for a short time, the genre made its way into global dancefloors.

Tres’ experience was arguably more underground and, it turned out, being too young for clubs was no real issue when the real fun was happening in living rooms. “You had crews doing poppin’ parties in like, Compton, Long Beach, Paramount", he explains between sips of a strawberry smoothie. “There might be a rapper part of the crew and a beat maker. It got real colourful, everybody started wearing skinny jeans.”

Tres was part of a crew called “Caddyville Wood Pushers” (owing to their love of skateboarding and being “sassy,”) who would dance in these parties, wearing their colors, purple and red, and expands on some of the scenes fashion details: “It was always a competition to see who could wear the most Chucks , so everybody had, like, 50 pairs...That was a whole thing,” he reminisces.

His mum lived in an area in the projects called the Wilmington Arms, before moving in with his grandma in west Compton, and the soundtrack to his formative years paints a picture of a double life: “If I was at my mom’s house I could listen to rap. If I was at my grandmother's house I had to listen to…oldies,” he laughs. The “oldies” in question include mostly gospel, that he drummed along to in church, the local Church of God in Christ ministry, and he sinks back into his chair and reels some off: the charismatic bounce of Kirk Franklin and devotional, husky harmonies of Reverend James E. Cleveland. His rap playlists included DJ Quik, and later the pioneering artists who continue to inspire him, Kendrick Lamar, Kid Cudi, Pharrell.

His own music now, is a thrill of modern, gritty synth-laden rap, influenced by elements of Chicago house, R&B, and years of DJing. It’s a product of an eye attuned to see creative expression everywhere, and led him to being a dancer, DJ and artist. It was the pulsing, luxurious sleaze of his debut single Controller in 2017, that led to the track being played in clubs, parties, and seeing him hailed as “LA’s new dance king,” and his acclaimed 2018 follow up was a self-titled EP that took us into the club at night, complete with dark basslines, injections of Afrofuturism and techno. Last year’s Black Moses EP, so named after Isaac Hayes’ 1971 album, arguably, gave us a more intriguing and distinct point of view, of sex, power, and reimagining a one-dimensional view of black masculinity.

His DJ and dancing background all contribute to his ear, which makes for an electric sonic charisma – after all, who knows how to make people dance better than dancers? Even today, when he’s thoughtful and calm, it’s the quiet fun that makes him immediately likeable. The night before we speak, I think he might have forgotten we had a chat booked in, and instead I just happily watched him on Instagram Live chatting to fans, and scroll through videos of his dancing on his archived stories. Bathed in blue light, his live shows are bewitching, complete with crowds with hundreds of hands in the air jumping in unison, fans breaking out in dance circles, and generally, having the best time of their life. It felt like a kind of therapy, watching in isolation languishing in a live experience as respite from this strange moment.

Oh yeah, you got to dance for the soul...What else is there?

In another life, Tres might have been a social worker, studying the subject at Oral Roberts University, in Oklahoma. We talk about the roads that led him there, namely, being raised by his great grandparents, then being made homeless after they passed away which made him keenly aware of the need for community support. “When she passed away I was 17, so I was homeless and I didn't know that there were resources that I could use because I was graduating and stuff. I didn't have money, I didn't have clothes.” He references the period on Black Moses, rapping, “I used to ask for change in the streets/Now I'm changing the streets” which takes us to the point at a crossroads before he met a peer counsellor that showed him another route. “When you're in foster care or the system, they have transitional life specialists, they're people to help you and stuff like that. So I met a lady and she helped me. I got in a lot of life skills training classes and started realizing the possibilities of what I can do.”

After realising that he wasn’t cut out for a 9-5, he says, college allowed him to interrogate his creative identity, and go on to study music production and composition instead, which allowed him a different kind of human connection. “The music kept calling me,” he grins.

The call of gluttonous, soul-shaking house music came courtesy of spiritual experiences, also known as, the first time he heard the euphoria of Patrice Rushen’s joy-filled disco injection, Haven’t you Heard. “When I discovered house music and techno, I found a black art genre built by my people” he smiles. “I feel like I'm the Compton house music king. I want to push the genre.”

He began making club music that pays homage to its black and Latinx queer origins, and his gender fluidity, he says, allowed for a spiritual release and expression in all forms after years of being around “hard” guys in the projects. “I'm able to be a little bit more braggadocious and sassy,” he says between sips of a strawberry smoothie. The music sounds like club music, the result of dancing in spaces that allow for expression in all forms. After all, dancers are uniquely tuned into the architecture of physical release. He sends me a song that he’s in love with might sum it up, that he says he wants to play at his wedding: Phreaky Motherfucker, by Mike Dunn. I listen to it after we talk. It’s an uncompromising declaration of joy, ass eating and desire in three and a half minutes: “I don’t wanna be a freak/but I can’t help myself.” You can imagine his knowing grin as he moves to it, and it makes sense. Even when he’s thoughtful – like today – he’s fun, even when his sentences drift to nowhere, he’s magnetic.

This low-key but present braggadocio might be why it feels particularly wrong to see Tres contained within a screen. It’s an image we’re getting used to, of grainy, jerky images of faces we can’t be with in real life, but somehow seeing Tres in this context is uniquely strange – he’s an artist whose work rejects containment and thrives on being in the world.

He’s sighing as he reels off outfits that aren’t being appreciated. “I got these leather pants. My pink polka dot house shoes I'm wearing I really like. I've been into chokers lately from the women's section….I got the best clothes”. It was the house scene, alongside the uncompromising genius of artists like Prince and George Clinton who he says, inspired him to challenge and liberate a one-dimensional view of black masculinity in music.

Dancing has the power to celebrate communities on the margins by the very nature of just being.

“We have polarity: feminine emotions and masculine feelings,” he explains. “And so sometimes growing up being around a bunch of hard shit, you try not to cry, you try not to bear your emotions, you try not to speak about things. It was so impactful for me to see dark skinned men and see them as kings.” He mentions how his gender fluidity impacts the music, allowing release that is spiritual, as well as aesthetic. I mention that Sexy Black Timberlake from his 2019 EP has been sampled, chopped and screwed in London clubs and he smiles, like feeling sexy is the motive. “I'm able to be a little bit more braggadocious and sassy.”

For Tres, managing the light and the dark, and locating beauty is all part of his practice. We talk about the excellent Brilliant Ni*a, from the Black Moses EP, a track in part, inspired by the US prison industrial complex. “My brother went to jail when he was 16 and he probably won't get out until he's 40-years-old” he says. He recognises the particular penalties of black men who have their stories taken out of their hands, collectively and negatively labelled if take a wrong turn in life, or do something negative. “Fuck that,” says Tres. “I'm brilliant, I'm good, I'm beautiful, I'm proud.” He’s rewriting stories, that include his own: his early years of visiting the family run fish market on his corner, getting ice cream at the now-defunct Compton Swap Meet, singing gospel songs in church. The last book he bought his brother on a visit encourages him to reject external barriers: The Mastery of Self: A Toltec Guide to Personal Freedom* by author and spiritualist Don Miguel Ruiz Jr.

Tres is explaining that he can’t not be political, by virtue of being a black man in America, when we discuss his current single Weedman. It’s the debut release on his newly launched label called Art For Their Good, a psychedelic pulse of g-funk for a post-Dre era, where he says that he’s attempting an examination into race disparity and weed use.

While medical marijuana is legal in LA, (in fact, there’s a dispensary right across the street from Tres) the war on drugs still disproportionately impacts black people. A landmark 2019 ACLU study found that despite roughly equal usage rates, black people are nearly four times more likely than whites to be arrested and charged for marijuana use. Tres takes a deep inhalation of a joint and I watch the smoke billow against the screen as he breaks down the policing for the cheap seats in the back: “It’s racist like a motherfucker.”

It’s not just policing that Weedman is about, though. “Wait,” he instructs, “let me give you the definition of weed.” He pauses for a second and I hear the clicking of the keyboards as he tries to illustrate disparity: “A weed is a wild plant growing where it's not wanted and in competition with cultivated plants,” he reads. “That just reminds me of when I went to college and was around all these kids that were ‘cultivated,’ I didn't even know that I needed to have a planner.”

The project has fascinating details – when we discuss the Blaxploitation-inspired aesthetic of the Weedman video, filled with notes of Shaft and Super Fly, as he jubilantly dances amongst the ‘70s decor of his living room, shots to a tantalising large stack of of weed on the table, as he dials his dealer on a brick phone. Talking about it, he unexpectedly takes me to the unintended beauty of Watts in south LA. “It was a really thriving Black community at one point but when the riots happened it messed up everything” he says, in references to the 1965 Watts riots which centred around an act of racialized police brutality and led to scorched pockets of Watts which never got fully regenerated. “So, when you walk down the street it still looks like it's from the ‘70s and stuff, it looks like a Blaxploitation film”. He uploads some of the joyous choreography from the Weedman video a few days later to his Instagram, hitting the beats with two friends dressed in the green dungarees and tangerine beanie in the living room. Tres brings the nostalgia and beauty of a Compton now and then through the story of black music heritage and excellence. It is always, reverently, in the background; if not visually, through a creative lens born from early years dancing in and around the city.

For the foreseeable future, plans for international touring and Coachella performances are on hold. It's time to create home again, and Tres mentions the intended décor additions of candles, fairy lights on his bare walls, and stacks of pianos on the floor waiting for a studio. Having the world closed off for a brief while makes no difference to him – the spirit and magic of Compton seeps through the walls, into his soul and connects him to a musical legacy that came before him and to come. It’s fair to assume that he’s making music, with an appetite for a debut album from fans. Before we sign off, I ask him about dancing as warfare, or, the idea that the divine power of moving your body can transcend anything else that exists around you. Like Joe Smooth or Frakie Knuckles before him, who paved the way for club spaces as sites of political visibility and physical emancipation, you get the sense that Tres is part of a lineage of artists who believed the dancefloor was a site of activism, empowerment and above all, a reclamation of space in all forms.

He nods, “I've just seen too much and so I have to see it as powerful. Growing up, I've been harassed by cops. I've been beat up for different things and picked on and stuff like that. So that's why I want to do music...I'm infatuated by the fact that I can be from a small community somewhere but I can connect with someone in a whole other country and make people move”.

You can feel tracks like Controller two years later, still pulsing through your body when it plays – limbs outstretched, waists flexing, a release of inhibition as it demands that you submit. Dancing as warfare has the power to celebrate communities on the margins by the very nature of just being, of having the audacity to luxuriate in dance as respite from the oppressive systems of a world outside. As I imagine him pushing pianos aside to make a dancefloor for the foreseeable future, he reaffirms a philosophy to get us through the times: “Oh yeah, you got to dance for the soul...What else is there?”