London-born photographer Caleb Stein moved to Poughkeepsie in 2012, a small town in Dutchess County, a two-hour drive north of New York, to attend Vassar College, one of the most respected liberal arts colleges in the nation. Poughkeepsie has a population of less than 50,000, and before he arrived there to study Art History, Caleb couldn’t have foreseen the monumental effect the quaint little town would have on his life.

Once settled in his new home Caleb began working as a waiter to pay the bills. At school his classes opened him up to thinking of images as stories. While studying he met Magnum photographer Bruce Gilden, renowned for his raw and striking portraiture, and became his studio assistant.

They went through Bruce’s entire archive of images together, and Caleb helped him move through a huge backlog of negatives that had never been looked at before. “I started to focus on bodies of work more than the power of a single image,” Caleb says. “It was a very formative experience. I think it slightly demystified things for me as well, because I came to realise that it takes a very long time to make work. It’s really a day in, day out thing. There can’t be time limits.”

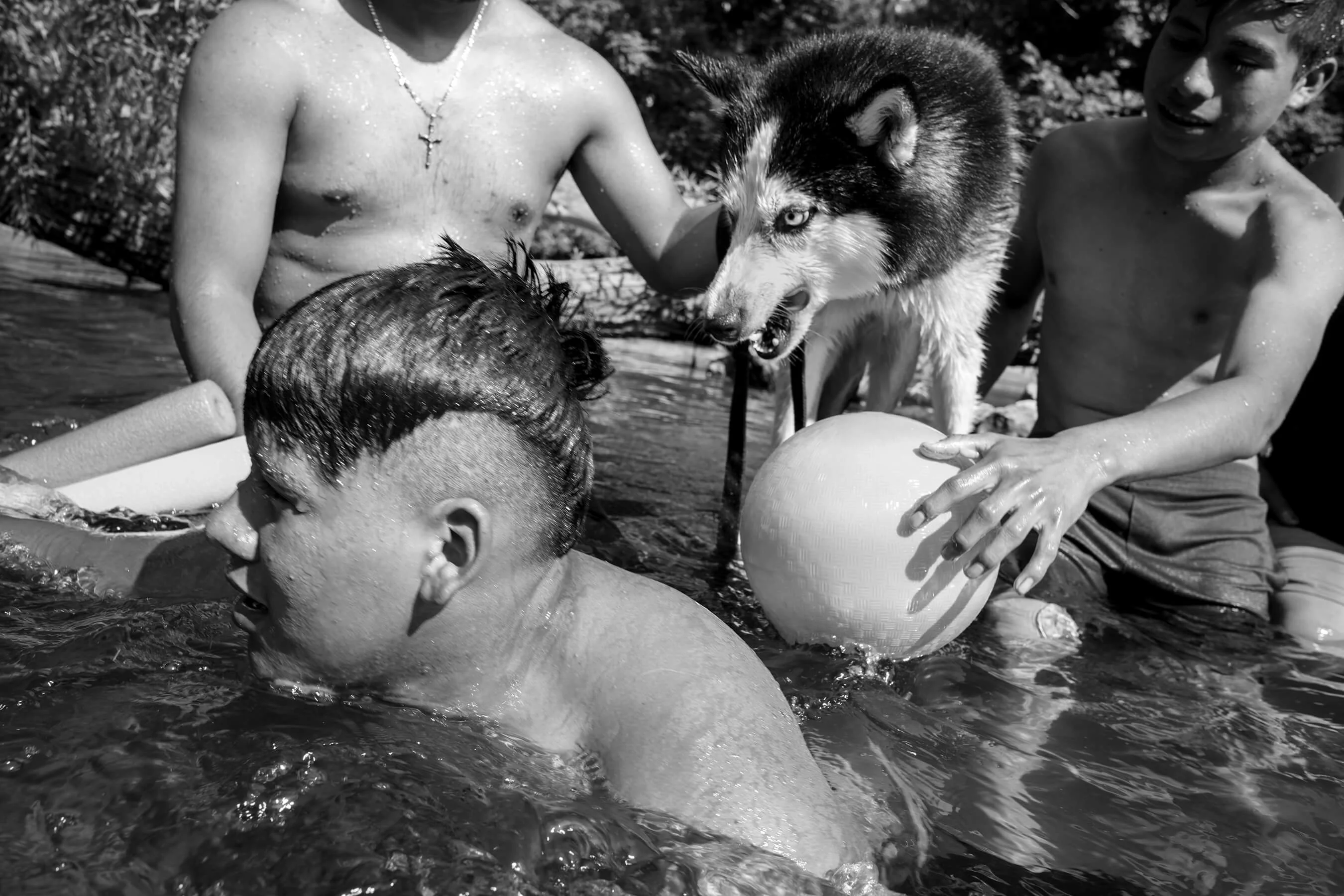

His time with Bruce afforded him the perfect chance to work on his own photography. He began photographing what he saw around him in Poughkeepsie, from the communal watering hole to the basketball courts to the scrapyard. Caleb had to work through certain questions about his own photography style and signature, and was lucky enough to be able to use Bruce as a soundboard. “There’s something that I’m drawn to which is a level of emotional intimacy and I think he is also drawn to that so it was good to have those conversations with him,” he says.

The watering hole was like a paradise. Poughkeepsie became my home.

Before moving, Caleb had never spent much time in small towns at all. “I had this conception of small-town America being something out of a Norman Rockwell illustration. Sort of wholesome, something like a folk story, like a Grant Wood painting,” he says. On top of this, when it came time for the 2016 elections, Dutchess County was almost neck and neck in the vote between Donald Trump and Hilary Clinton, and the difference was miniscule. “There was that tension,” Caleb says. “I was interested in whether my preconceptions about life there and about this political uncertainty would remain after walking the same spaces over and over again.”

When he first arrived, he felt the disconnect between the town and the university, and noticed that a lot of the other students, like him, weren’t sure where they fit in to the town’s picture. “With time I just became dissatisfied with the student bubble, and that’s when I really started branching out,” he says.

He would spend his free time exploring, taking his camera with him wherever he went, walking for miles at a time. His favorite spot was the watering hole, located on the outskirts of town. Right next to a drive-in movie theatre, “it was like a paradise,” he says. He regularly swam at the watering hole with the other locals, and made friends from different backgrounds.“It became my home,” he says.

This is the sort of person Caleb is. He interacts, he builds relationships and he embeds himself in the community. He befriended one boy called Kaleb at the watering hole. “Every time he’d see me he’d shout ‘Caleb with a C!’ and I’d shout ‘Kaleb with a K!’ We played catch together and I taught him how to swim. His family and I hung out a lot.” Caleb puts time into these relationships with strangers, and in this case he felt rewarded when the boy came into the restaurant to see him while he worked.

If something hammers you over the head it’s not doing very much.

These interactions bring so much to the series, he isn’t simply an outsider looking in on something he doesn’t understand. “I had an outside perspective but I lived there for so long that I grew to love the place,” he says. “So that might have given me the opportunity to see things slightly afresh.”

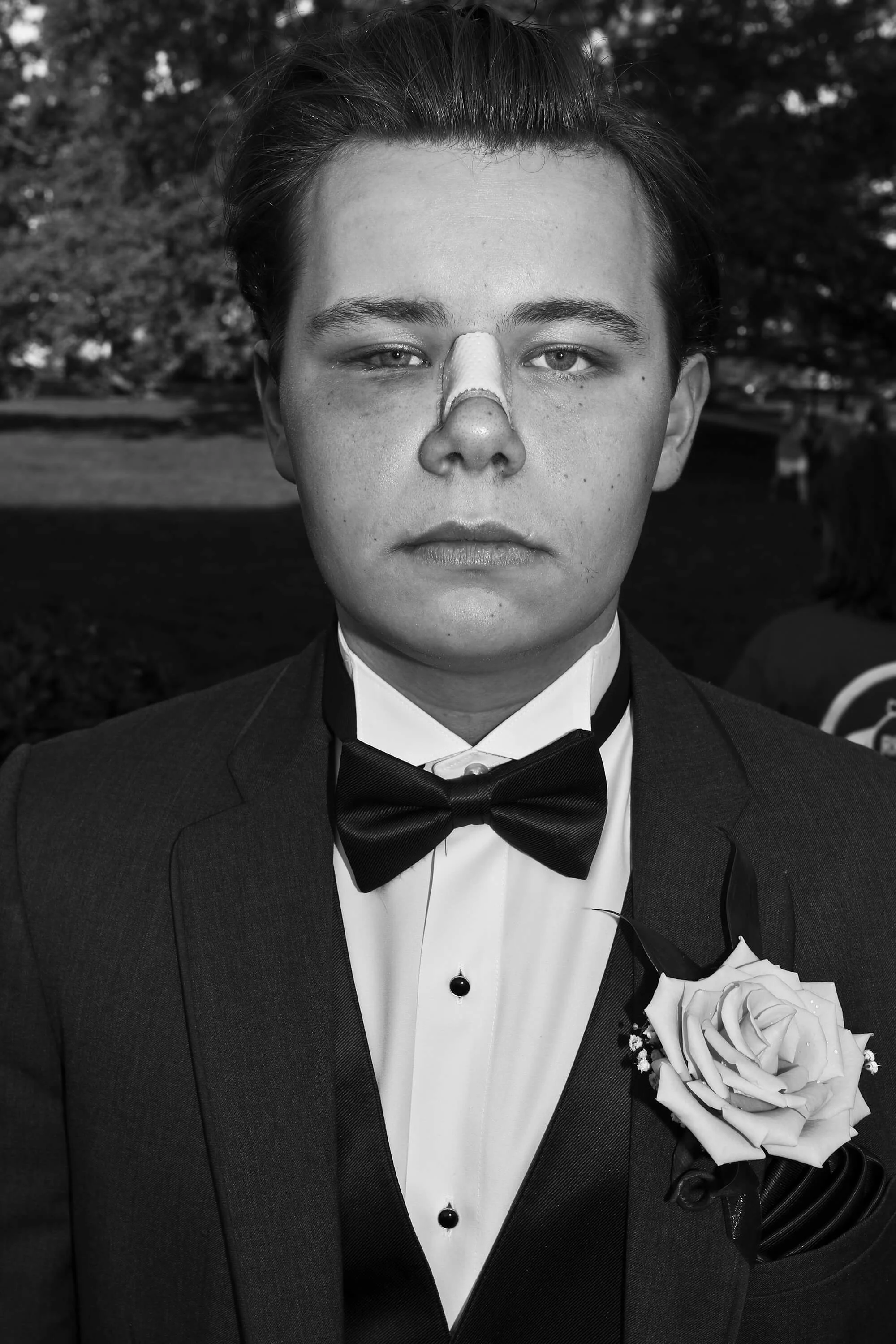

One photo that stands out in the series is a shot of a teenager on his way to the school prom. In his summary of the series Amitava Kumar, a professor at Vassar college, describes it as a “fine, even tender, mix of contradictions,” and this rings true. Smartly slicked-back hair, a poorly-tied bow tie and a flower on the lapel are offset against a bandaged nose and a black eye. But as with all the photos in the series, it’s so much more than what it appears. “I’m hesitant to share because I like the mystery of it,” Caleb says. “He stood out to me in a crowd, and we had a brief interaction. I was amazed at how much he opened himself up to me in such a short amount of time.” At Caleb’s request, the backstory remains a mystery. “If something sort of hammers you over the head it’s not doing very much, is it?” he asks. “I prefer uncertainty.”

There’s something beautiful about these little interactions, from the short conversation with a bruised prom date to the jokes with a young boy around the different spelling of a name. Like his photos, Caleb finds beauty in the mundane, in the simple things. “I try to look for that in anything,” he says.

In Poughkeepsie, he was challenging himself to make work out of the everyday, on his own doorstep. “It was extremely difficult at first because I was conditioned to think that I would need something spectacular to make a strong image,” he says. “So I had to work through a lot of my own conceptions and expectations and disappointments. It was a lot of hard work, and I would come home completely empty-handed for months.”

He still sees the misconception amongst the big-city elite that there’s nothing of value happening in small towns like this one, but his own story is one that debunks this tired stereotype. He met his wife there and fell in love, he had a rich education there, an incredible mentor. “I had a lot of moments alone where I realised something about photography or about life. It taught me that there can be great things anywhere if you look for them,” he says. “I think about Poughkeepsie everyday.”