In the summer of 1992, the most acute reflections on the social and political ramifications of the Los Angeles protests – which followed the acquittal of the police officers who had savagely beaten the African American construction worker Rodney King – appeared not in a mainstream newspaper or a high-minded periodical, but in the punkass feminist zine Ben Is Dead. It was a brilliant, witty, funny, overwhelmingly cool magazine created and edited by Deborah “Darby” Romeo and Kerin Morataya: two linchpins of the downtown LA ‘90s music and art scene.

Commissioning a dazzling array of contributors from marginalized communities and taking pride in doing things differently, these two badasses put out a very good thing for – as is always the case – too short a time. Writer and magazine expert Paul Gorman hunts down the excellent people involved in making Ben is Dead, to piece together the story of how they did it.

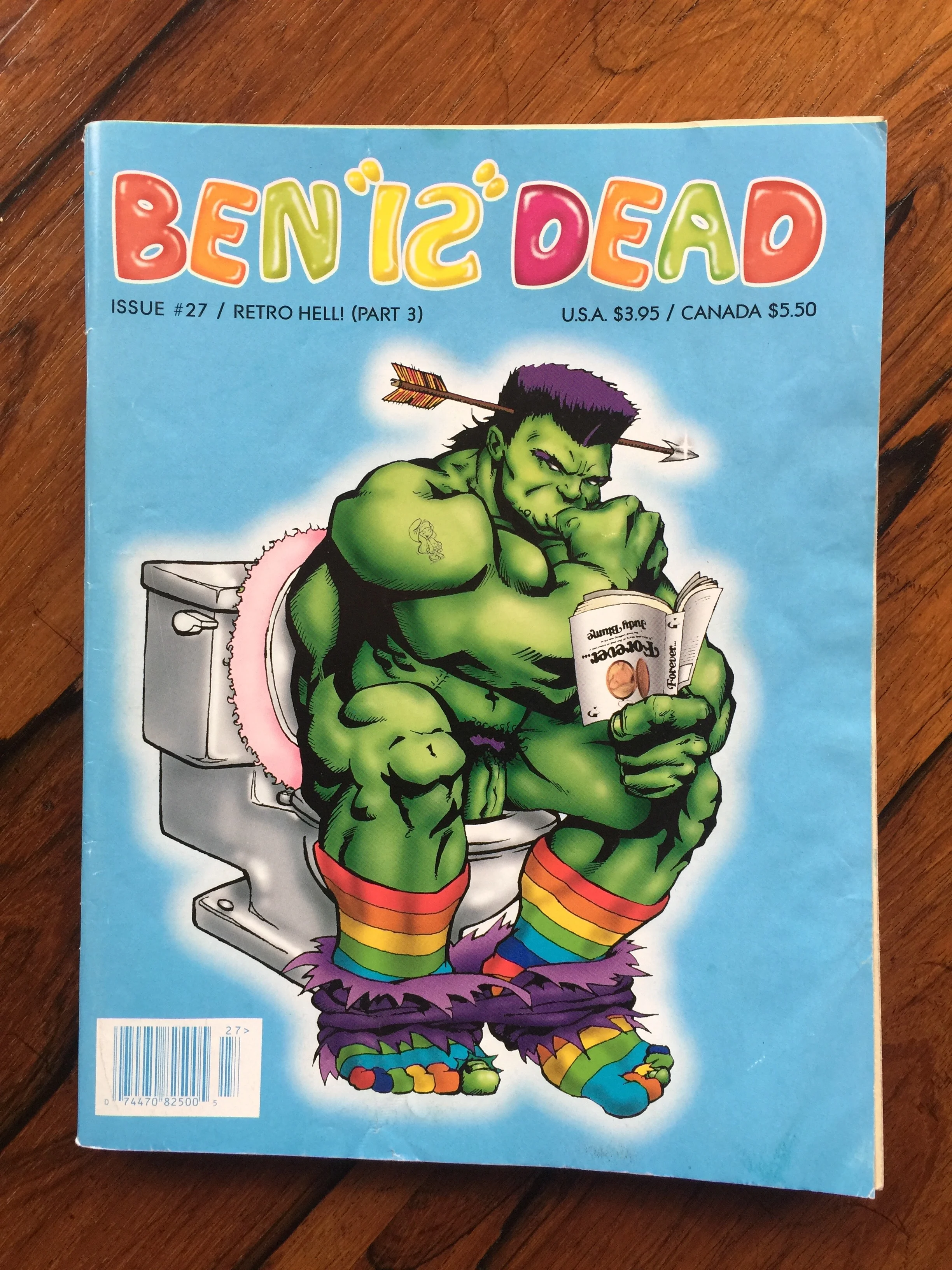

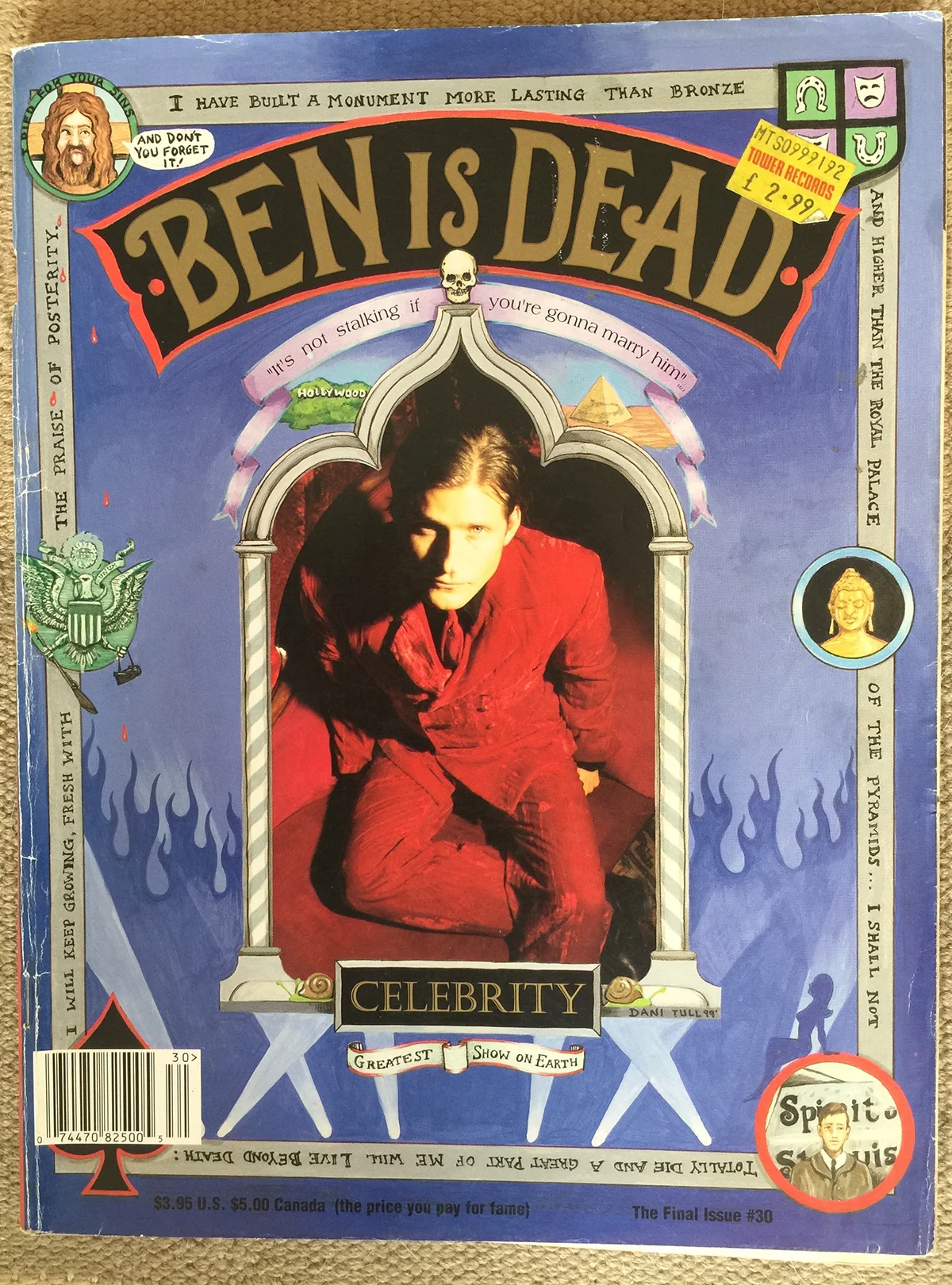

I miss Ben Is Dead. You may not have heard of this sassy, caustically funny zine, which ran for 30 issues for over a decade until the late ‘90s, but it occupies a unique place in the story of alternative publishing as one of the shining beacons of Western counterculture.

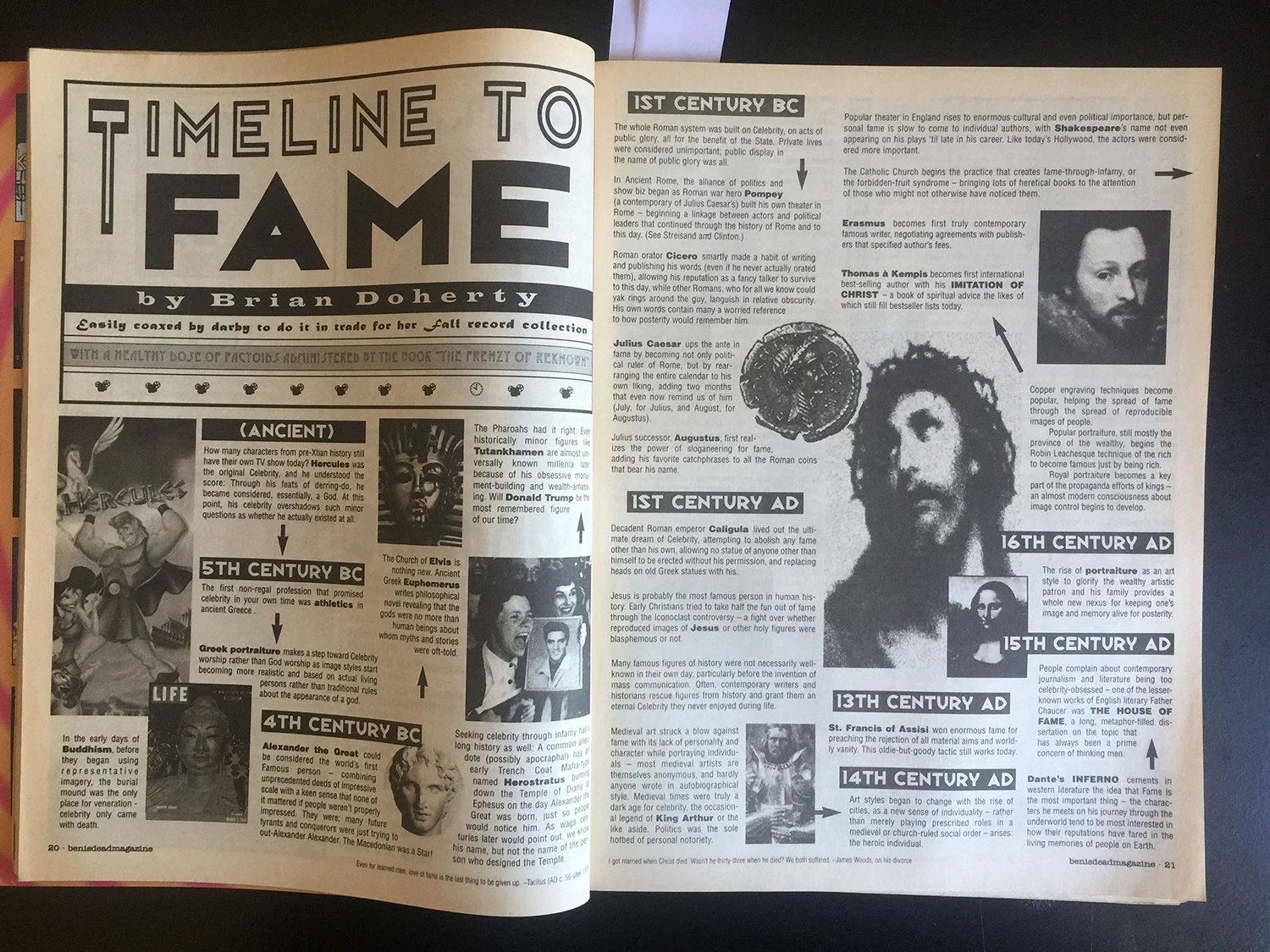

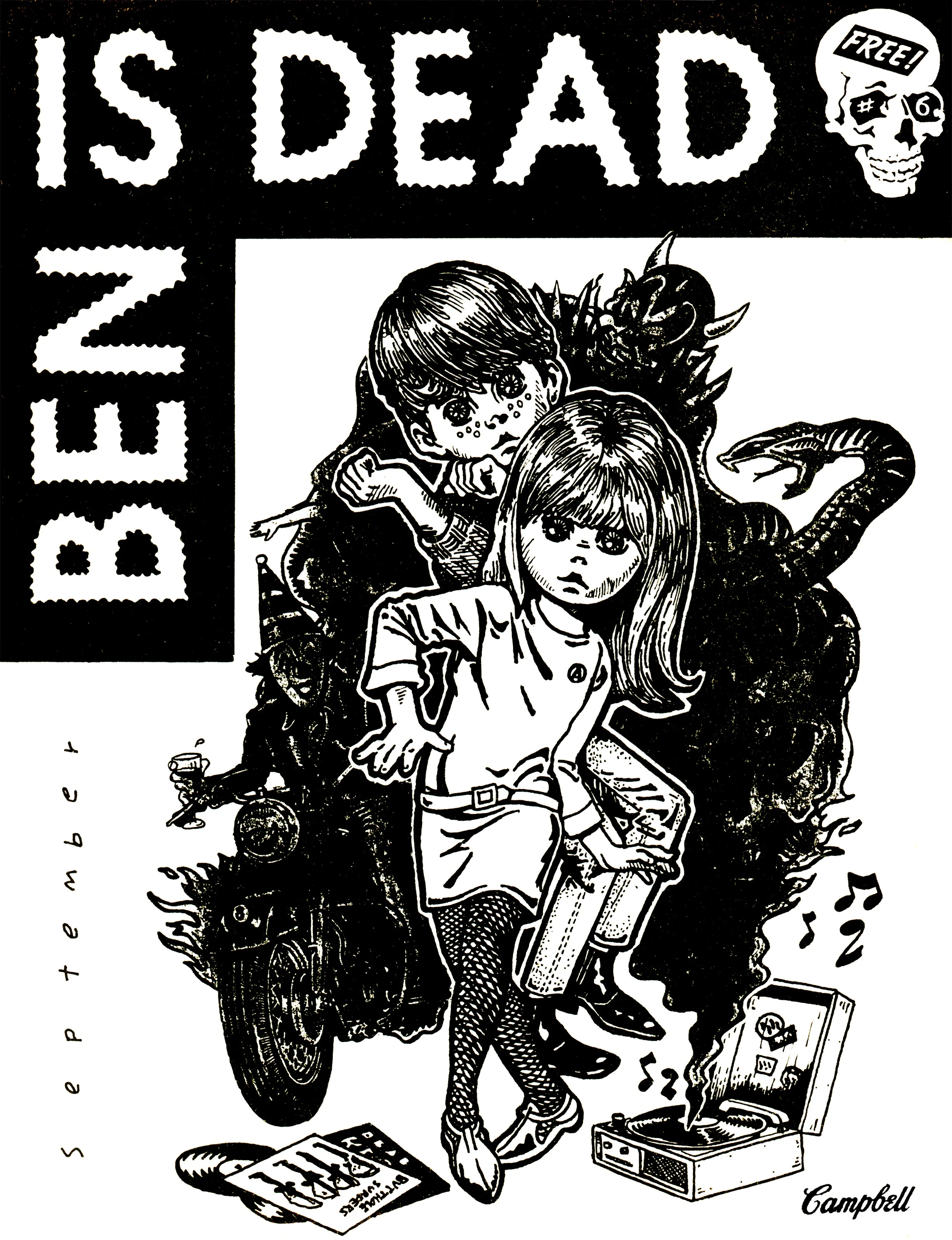

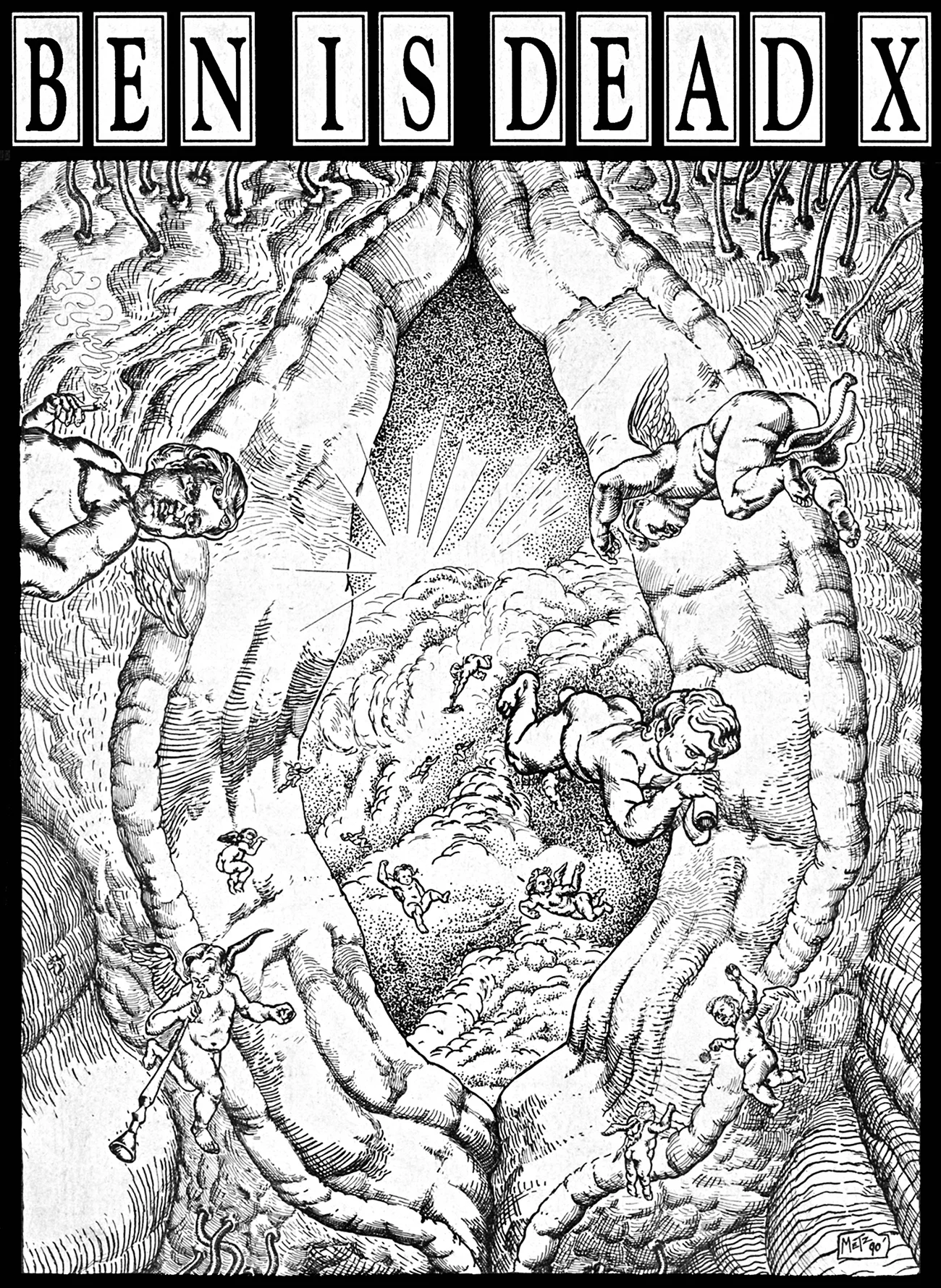

Edited and written by young women and a dazzling array of contributors from marginalized communities, issue by issue the LA-based magazine steadily established breakout appeal from its beginnings as a free black and white newsprint quarterly rooted in the regional music scene. This was a time when zines proliferated in the US, where cities and towns had spawned individual punk-inspired independent music circuits. Small circulation home-made print publications took their cue from the great DIY aesthetic of pioneering ‘70s titles such as Sniffin’ Glue and provided a network of alternative media bringing the latest news on tours, record stores, venues, art galleries and films to young musicians and fans.

In late ‘80s Los Angeles, which was dominated by the long-established zine Flipside, young alternative Angelenos rejected the big hair metallists hanging out on Sunset Strip and gravitated to the scrappy, low-cost neighbourhoods around Hollywood Boulevard and Melrose Avenue in adjacent West Hollywood. These days a byword for corporate uncool, Melrose was at the time analogous to London’s Camden, complete with a raggedy selection of art spaces, record shops and boutiques. With a web of great clubs, including Jabberjaw, Coconut Teaszer, Al’s Bar and Raji’s, LA was ripe for a radical new magazine making a break with the past.

“Initially music was the unifying theme,” says Deborah “Darby” Romeo, who launched Ben Is Dead in 1988 as an LA graphics major after her father gave her one of the earliest Macs (one of those 13” monitor, dumpy, floppy disk drive SE1/40s). She conjured the title from her failed marriage to a French punk rocker called Ben she met while studying at the Sorbonne (“Ben is dead – to me”).

By taking as its overarching subject “Mother,” issue 10 of BID in 1990 inaugurated the magazine’s most successful period as the editors imposed specific themes on successive editions.

“I loved punk, industrial, noise, the stuff coming from Amphetamine Reptile, but wanted to look beyond that,” adds Darby. “Having a theme meant we could focus rather than being all over the place. There was also a slightly obsessive side to it, that thing of not being able to stop going off into different tangents and perspectives.”

This compulsiveness meant that, by the early ‘90s, there were months-long gaps between issues, making the experience of encountering the latest BID all the more exciting, particularly when the subjects ranged from “Broke” and “Obsessions & Bad Habits” to “Modern Transmissions & Sensory Overload” and “Disinformation.” Gaining international prominence (“I was mailing copies to people all over the world,” confirms Darby), BID became packed with ads from underground labels and the faux-indies which had been launched by the majors to cash in on the grunge boom, though the BID crew viewed the rise of the genre uneasily, and often mocked it for what it was: the corporate response to the messily organic grass roots movements in which they participated.

The zines had no protection. Once the chips were down it was easier to start stiffing us.

And BID’s political edge, wiseass humour and kaleidoscopic visual presentation also gathered fans among the diverse range of interviewees they chased down, from the late Genesis Breyer P-Orridge to Duran Duran’s Simon LeBon, as well as those in the highest echelons of the international entertainment business.

“Darby and I were quite similar in that we could be consumed by a current event but at the same time we would make jokes or be irreverent about it,” says BID co-editor Kerin Morataya, who joined Darby a year or so after launch. “We were lucky in that we found like-minded people with the same twisted sense of humour. Ben is Dead was like a magnet; it kind of came together magically.”

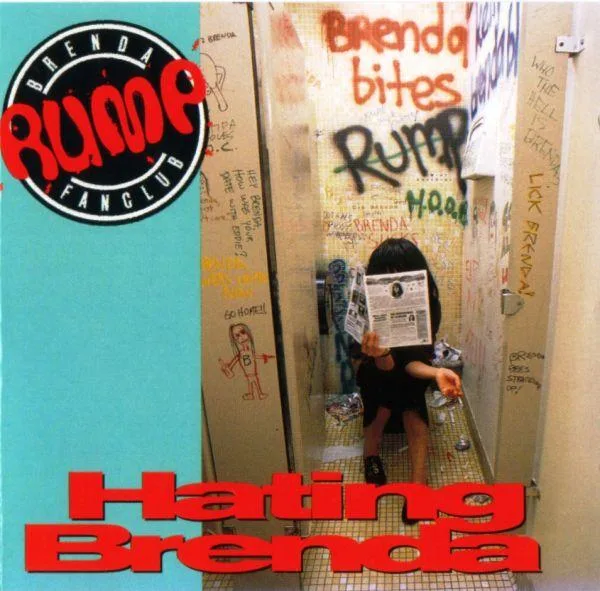

Overtures came from none less than Vanity Fair, which appointed Darby and Kerin contributing editors with their fingers on the pulse of America’s youth. They attracted the high-falutin glossy’s attention after publishing a spin-off newsletter satirising the actress Shannon Doherty, at the time one of the biggest stars in America for her role as the troublemaking Brenda Walsh in the hit TV series Beverly Hills, 90210.

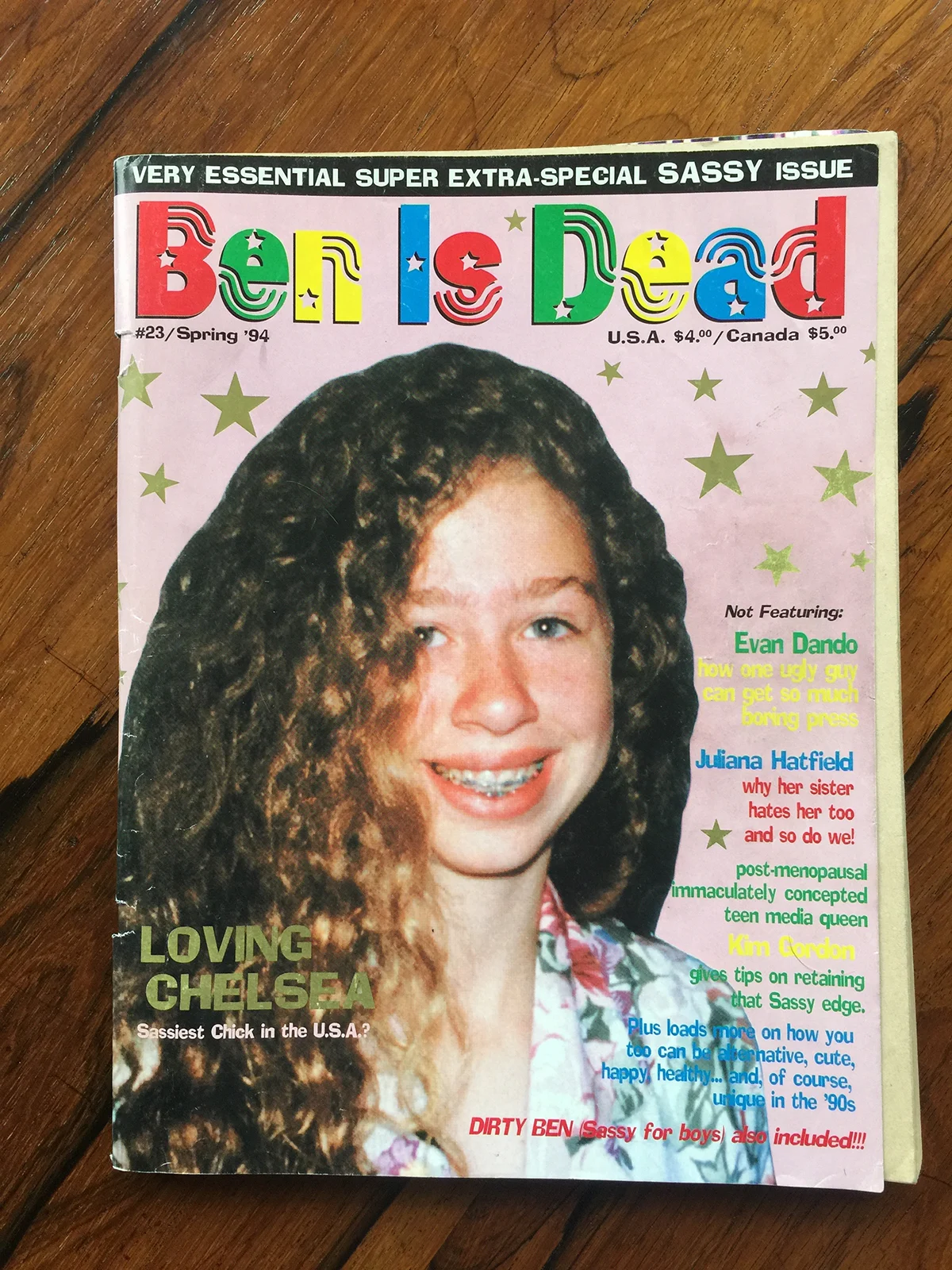

A case in point was BID’s hilarious take on Sassy, the big-selling major league magazine of the early ‘90s aimed at young women. This came about when Darby and Kerin entered a contest to edit an issue of Sassy but were barred from winning because of their age and the fact that they were media professionals. For the cover star of their tribute, Darby and her cohort chose President Clinton’s daughter Chelsea, who was at the time regularly derided as nerdy in popular media.

“We thought Chelsea was gorgeous and deserved paying homage to,” says Darby. “People were so mean to her and that made me so incensed – she was just a kid. That’s also the issue where we ran into Bob Dylan. We were interviewing some band in a recording studio and he walked passed so I encouraged my Girl Friday Jessy Jones to ask him what Sassy meant to him. She barged into his studio uninvited and he pulled out an answer in one second: ‘Insolence’!”

Kerin recalls sending a copy to the First Daughter: “We got it to some general at the White House but never heard back, so we don’t know whether Chelsea even saw it.”

Darby supported herself with a day job in the art department of the giant advertising agency Grey, and credits the publication’s distinctive flavour to the team which gravitated around her. “We were a collection of weird people, in a good way, and without the internet we developed our own collective consciousness,” says Darby, these days a massage therapist, having moved to Hawaii soon after BID closed to indulge her passion for surfing. “This was an amazing bunch who weren’t falling for the mainstream, but sharing information from outside of the norms.”

The cornucopia of contributors included performance artists Vaginal Davis (one of whose projects was the faux-Latinx group Cholita) and Lisa Carver of Suckdog, who respectively ran the influential fanzines Fertile LaToya Jackson and Rollerderby, while regular advertiser and frequent subject Helen O’Neill, of Melrose’s legendary goth/post-punk boutique Retail Slut, also produced her own mag, the memorably entitled Foetus Acid.

“Because I came from that zine background I understood what they were trying to do,” says Helen who, by stocking Ben Is Dead in her store, turned flocks of her customers onto it.

Meanwhile Darby says that in particular the support of Vaginal Davis, a significant figure in LA’s alternative society since the ‘70s, helped raise BID’s editorial game. “She had so much influence on Ben Is Dead because of how huge she was in our world,” says Darby. “When we did a zine event in New York, we flew her in to host it and 1,000 people turned up. She was an amazing inspiration for all of us.”

Without the internet we developed our own collective consciousness.

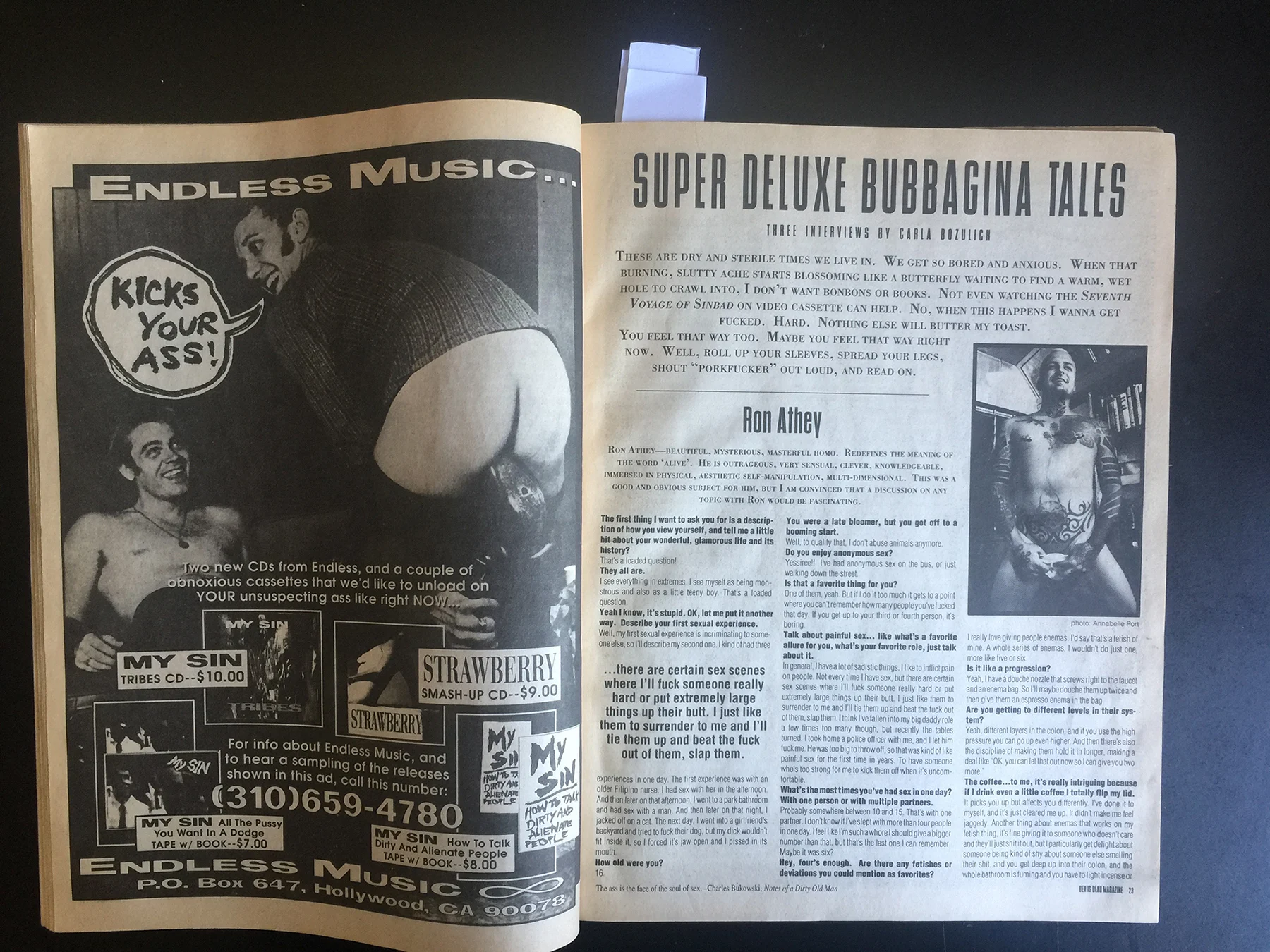

Writers such as Carla Bozulich of BID favorites Ethyl Meatplow (and later the Geraldine Fibbers), Mikki Halpin, who went on to become a high profile editor-at-large at such outlets as Glamour, the New Yorker and Refinery 29, Ron Athey, whose performance art centres on his body, and the author and stripper Patty Powers all elevated BID above its peers with a mixture of confrontational charm and insider access.

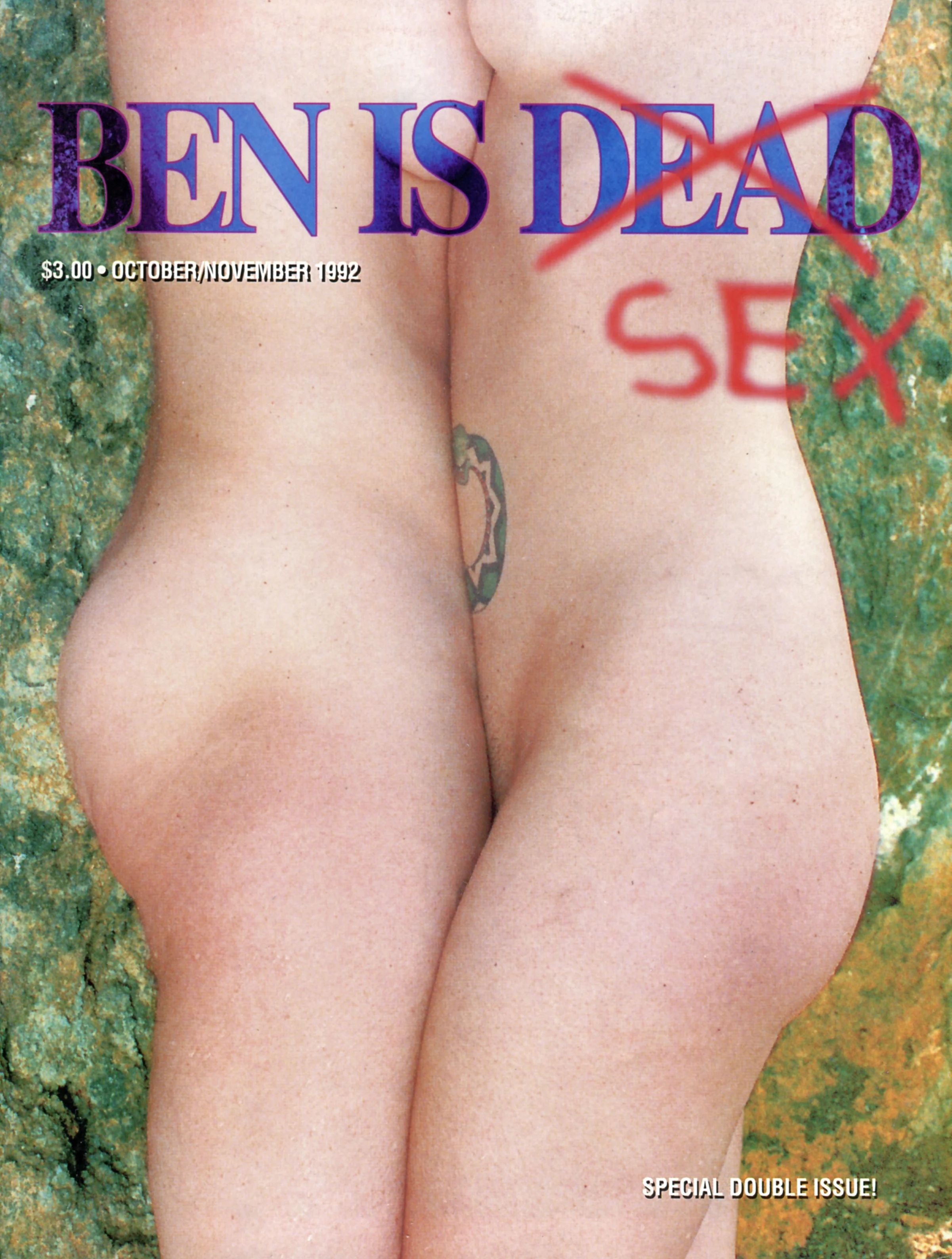

These contributors were all involved in the Sex issue of 1992, which became BID’s biggest seller at 20,000-plus copies and featured a cover image of Bozulich and Steak from the local band Steakhouse taken at the surfers beach Point Zeros in Malibu by in-house photographer “Wild” Don Lewis.

Soon afterwards, during an interview with Malcolm McLaren, Darby gave the late cultural iconoclast and former Sex Pistols manager a copy. He had, of course, operated a boutique called Sex with Vivienne Westwood in the King’s Road in the 1970s. “A few days later he called the Ben Is Dead hotline, where we told readers about upcoming shows and parties,” says Darby. “When we listened to his message, we heard him say, ‘I just read the Sex issue of your magazine and I thought it was absolutely…’ and the frigging answering service cut off! It broke my heart that I never found out what Malcolm McLaren thought of my Sex issue!”

As a British journalist working in LA at the dawn of the ‘90s, I wasn’t alone in being drawn to BID’s sardonic, raw-edged editorial attitude as much as to its eye-popping covers and layouts.

“I was one of those teens that thought Sassy wasn't cool enough,” says avid BID Fan Jennifer Brandt-Taylor, who was inspired by BID to start her own zine, Pesky Meddling Girls, in 1994. “Sassy was too poseur-y, with models dressed by stylists in faux-boho looks. But Ben Is Dead delivered everything that resonated with my too-cool-for-school brain: sex, weird music, LA characters, acid and pop culture through an always hilarious and ironic lens.”

“Ben Is Dead offered a sure and brilliant glimpse into the then-mystifying world of alternative culture,” wrote LA Weekly’s David Cotter, who also started reading the magazine as a teenager, a few years back. ”Each issue seemed more crassly erudite than the last. It felt indispensable and I picked up as many as I could, as often as I could. I knew that reading it cover to cover would counter the effects of the uncool, expanding my consciousness, atom by invaluable cultural atom. Ben Is Dead turned me on to artists and phenomena that were at once fascinating and terrifying, artists toiling at the absolute fringes of experience.”

These included a panoply of underground heroes, from Lydia Lunch in her New Orleans mansion, trans rockabilly artist Glen Meadmore and activist and author (and member of punk band Honk If Yr Horny) Nicole Panter to acid proselytiser Timothy Leary and radical dramatist Robert Anton Wilson.

David cites in particular the edition published in the wake of the riots in Los Angeles triggered by the 1992 acquittal of police officers whose savage beating of African American construction worker Rodney King was captured on video. “Ben Is Dead published an issue that was stuffed to bursting with reportage that critiqued the media as much as the violence itself,” recalled David. The cover image was of graffiti sprayed in an LA neighborhood badly affected by the rioting: “BAD COP NO DONUT.”

With that final edition in the bag, BID’s time was up and a new, much more commercially aware wave invaded its turf, including the local rival Boing Boing, which offered a music-based mix and has continued into the digital age.

Another survivor was an unprepossessing giveaway published out of Canada, the editors of which had clearly been paying attention. “We were much bigger than Vice back in the day,” recalls Darby. “They were sending me their issues to get coverage and I was thinking: ‘What the heck is this shit, this fluffy, fashion, fake-punk thing?’ But those guys were still ready to take it all on. I was over it.”

At the time, Darby was a member of the inner circle surrounding the author and shaman Carlos Castaneda. His death was also a factor in her decision to withdraw from publishing and leave LA for Hawaii where she has been engaged in political and social issues, including spearheading the hard-fought campaign which resulted in the 2018 ban on sunscreens containing chemicals harmful to coral reefs.

We were lucky in that we found like-minded people with the same twisted sense of humour.

Similarly Kerin has been active in immigration reform and rights in California, particularly in relation to the immigrant camps on the border with Mexico which are impacting the lives of many central Americans. And so the magazine’s main protagonists continue to champion the values which were a crucial part of the editorial mix.

Having got together in LA for a weekend of parties, club nights and gigs to celebrate BID’s 30th anniversary in 2018, the good news is that BID isn’t, er, dead. While Darby isn’t tempted to relaunch the magazine, she is currently working on a BID book and is also establishing a digital resource which will include covers and articles as well as her reading some of the zine’s most remarkable stories on social media.

“Because we didn’t put anything online for so long, it’s been totally out of the culture,” she says. “You can’t find much Ben Is Dead information anywhere. There’s no text and very few photos. It kind of keeps faith with what it was. We didn’t mass-market or even advertise. You came across Ben Is Dead by accident or by word of mouth.”

“Even at our biggest, Ben Is Dead was still underground.”