We might all have gotten a lot better at documenting and curating our lives, but the endless scroll can be a gruelling part of our daily lives that can take a toll on our mental health. Here, writer Christopher Hooton explores the relatively new and incredibly popular wave of artists posting quick, hand-drawn cartoons that communicate a hell of a lot with very little.

Top image by Hiller Goodspeed.

We live in a time of information overexposure. Our brains now take on five times as much information each day as they did 30 years ago, with one study equating this daily bombardment to 34GB of data. Our minds are buffering, our eyes are spinning Mac pinwheels.

Nowhere is the content avalanche more overwhelming than on social media. How many of us wake up in the morning, the veil of sleepiness still hanging over us, and within 10 minutes find we’ve opened our phones and commenced mainlining information? Images, videos, articles, adverts – a literally endless feed of multimedia, all of it in fierce competition for our attention. It’s a content war out there, and a maximalist approach tends to prevail. It’s high-saturation, high-contrast images with dreamy filters. It’s fast-cutting vlogs with the breaths trimmed out and hyperventilating news stories that demand your clicks.

Not a lot makes sense to me but art and humor do.

But amid the noise, or rather because of the noise, a new breed of artists are finding success with work that values simplicity and feels nostalgic for a time with lower production values and a sense of visual economy. Their creations have become oases of calm in my Instagram feed – necessarily crude, usually hand drawn and invariably creating a feeling with just a few flicks of a pencil. There’s a saying that originated in 13th-Century German philosophy, “Only the hand that erases can write the true thing.” It would seem to apply to drawing too, with these images often locating truth precisely because they leave stuff out, focusing in on specific moments and expressing them clearly.

The first artist in this burgeoning genre to come to my attention was Sara Hagale (@shagey_), an artist who has considerable sketching and painting chops, yet often favors a stripped-back style. Some of her recent creations include: Unfurling fingers; A dog’s face being held gently by human hands; A stick-man in a top hat drawing a single pencil line on a piece of paper; A scoop of pistachio.

Sara has amassed over 250,000 followers on Instagram, but she’s not on the platform to compete. “I never drew because I thought it would get me somewhere,” she tells me, “I wouldn’t want to put that sort of pressure on something I often rely upon for emotional relief.”

I can’t really explain why my art looks the way it does. To some extent, that’s like asking someone why an orange tastes like an orange.

Art came into her life as an immediate and accessible form of therapy. “As I got older and life became more complicated, as it often does, I began drawing as a way to not only express myself, but also as a cathartic release,” she continues. “After gaining a BFA in Graphic Design, I began expressing thoughts, feelings and ideas in a slightly different way.

“Sharing my work on Instagram was a way to keep a log of what I was doing, how I was feeling and what I was experiencing in my life. It was, and still is, a way for me to track my progress as an artist and as a person. I don’t cater to what people might explicitly be looking for. For me it doesn’t work like that, and it makes me sad when I see artists trying to produce what they think people want to see.”

Sara’s distinctive style is goofy yet elegant. Course yet tender. Sombre yet playful. There’s also a strong sense of geometry to it, her characters often looking like humanoid manifestations of math problems.

“I can’t really explain why my art looks the way it does,” she says. “To some extent, that’s like asking someone why an orange tastes like an orange.”

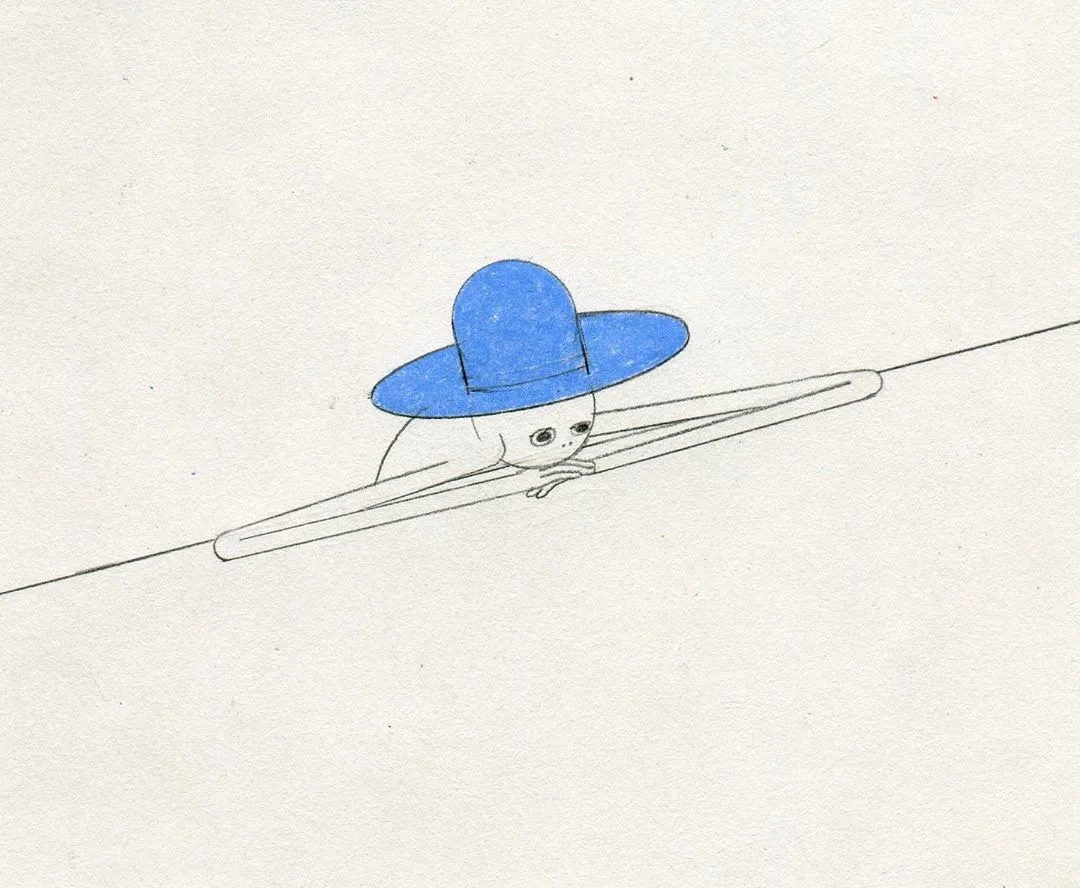

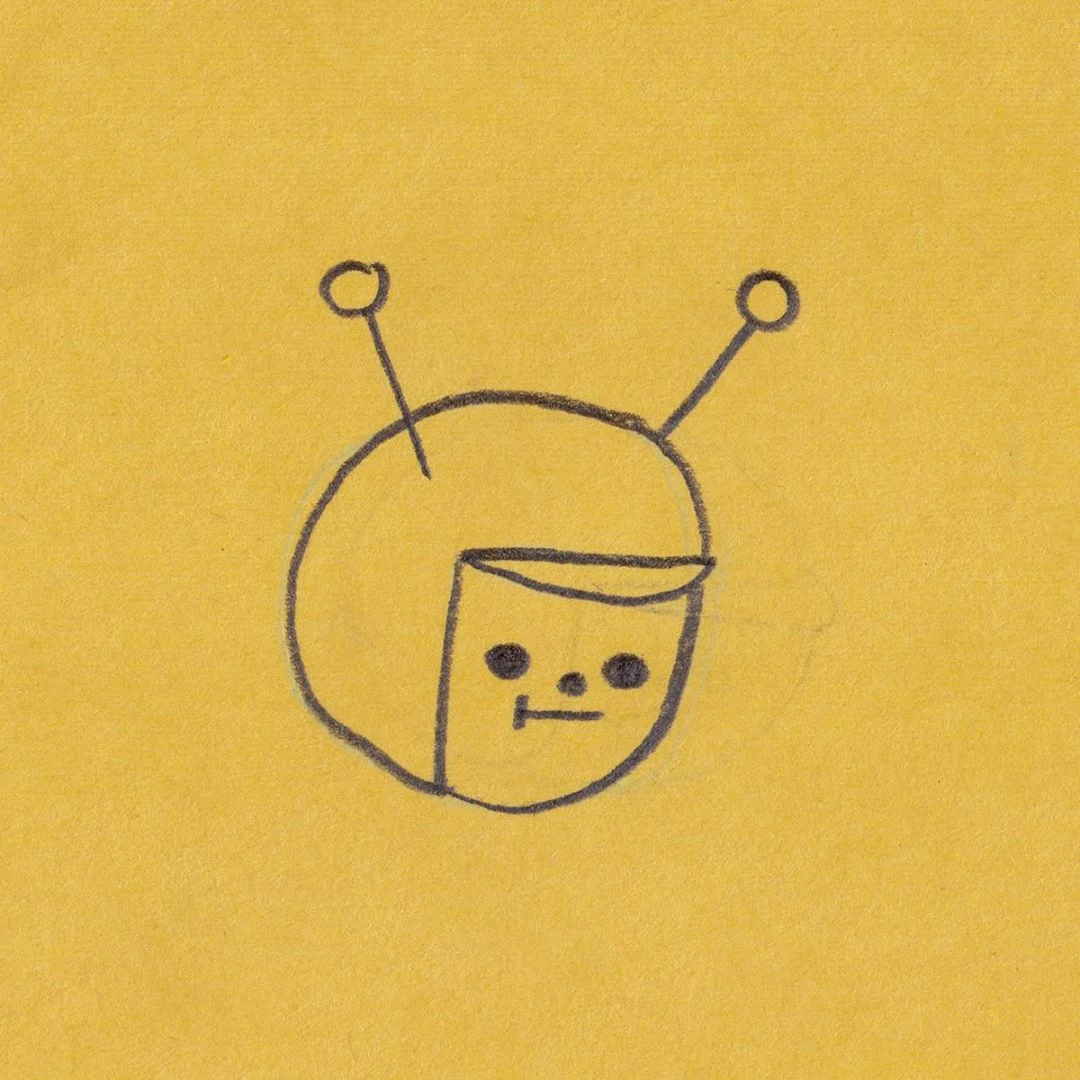

Nowhere is the power of minimalism and restraint better demonstrated than in the work of Hiller Goodspeed (@hillergoodspeed). How heartening is it that in these “break the internet” times of overstimulation, a black and white, 2D pencil drawing of a guy in a space helmet (complete with half-rubbed-out previous attempt) can draw over 15,000 Likes? I put this to Hiller. “Yes, that guy is great! Sometimes all we are looking for is a simple thing and it's nice when you find it. I think we could all use less words, in general.”

Hiller was artistic as a kid, but started drawing a lot more when he moved to Portland, Oregon in 2010. The fact that he was living out of a suitcase meant he didn’t have a ton of art supplies and needed to keep things simple. “It was okay if my drawings were simple and weird and dumb, because I had fun making them and that was all I cared about.” Hiller has since moved to Vancouver and works in a library, “generally quiet, peaceful places that have been a good compliment to my illustrative career.” Though Hiller’s also interested in sculpture and woodworking, currently churning out toy sticks of butter (“I don’t know what I’m doing but I keep doing it”), he’s known for his clean and uncomplicated drawings, which are often paired with Holden Caulfield-esque lines of wisdom and have been tattooed on people’s bodies the world over.

The work of Hiller and his peers is a descendent of single-panel “gag cartoons” that date back to the 1840s, and more recently of the web comics that boomed in the early years of the internet. But they represent a new genre within this tradition, one that more often than not deals with the rich vein of anxiety that a life lived increasingly online has unfortunately brought many of us. The relationship between art and viewer is absolutely key here, the images often serving to throw an arm around your and say, “don’t worry, I think all these thoughts too.” The images’ physical location among all the other content that populates our feeds – some welcome, some not – is crucial too. Popping up periodically as we scroll, these simplistic artworks simultaneously create a space, a clearing away from the noise, while reflecting back the low-level dread that underlies the preening game that is social media. “Usually my illustrations start as a single feeling which can be traced back to a tense or uncomfortable experience,” Hiller explains.

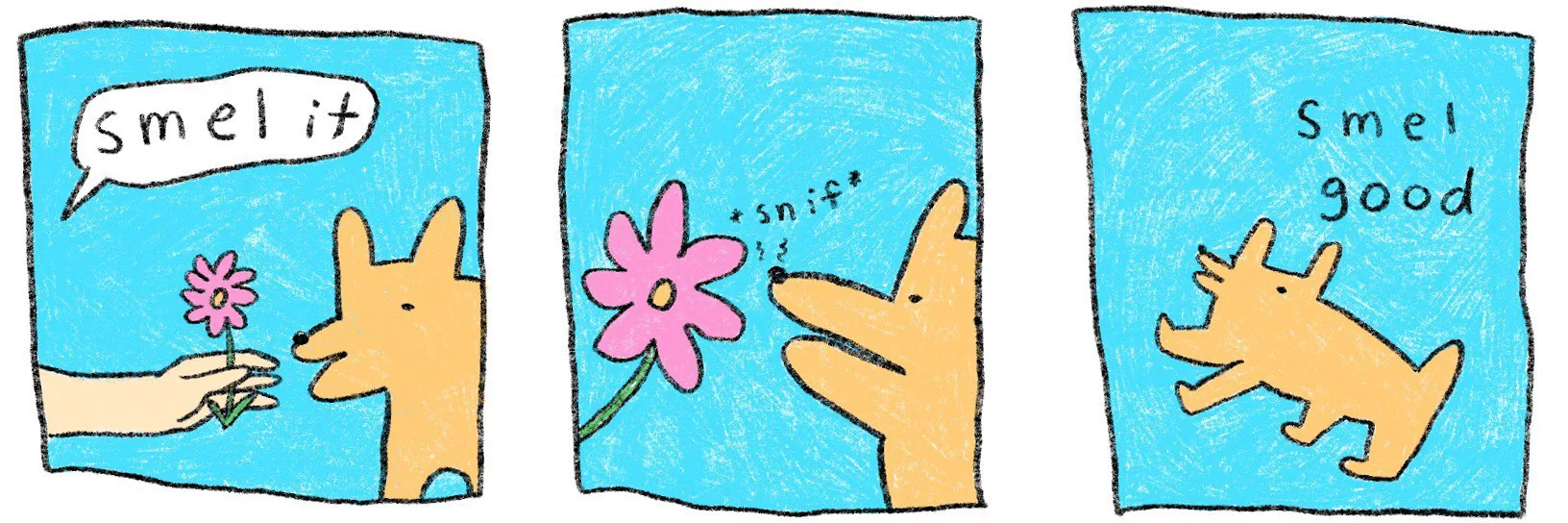

Anxiety and depression are everywhere in the work of Alison Zai (@alisonzai), whose drawings evoke TV cartoons aimed at pre-schoolers but deal with deceptively complicated subject matter, skewering ennui and probing the id. “So do u like, have opinions?” a dog asks in one image. “An unlimited supply,” the creature at the other end of the cell phone replies, while casually flipping a fried egg. In another almost Zen-like, cartoon, a character states: “I am reminding you of a memory that you otherwise would have forgotten.” “Thank you,” their friend replies, “many memories have been lost forever.”

Alison credits her work with helping cure her depression. “Not a lot makes sense to me but art and humor do,” she tells me. “I’ll have a bad experience, draw it, and now that I’ve mentally unloaded it on paper I never have to think about or deal with it ever again.”

Instagram is an incredibly valuable tool for a visual artist, enabling one to boost visibility of creations in a way that would have been much more difficult pre-internet. But in spite of their success and their clear affection for their legions of fans, Sara, Hiller and Alison all have misgivings about the platform. This uneasy relationship is woven into their work, but they all make it plain to me too.

“I think of Instagram as something I have to endure,” Hiller admits. “I use it often and it's a great way to share work, but there are reasons why any of us are creating work in the first place and I feel like Instagram can distract us from those. I hope that we can eventually develop more community-oriented institutions and get back in touch with what really matters to ourselves, as artists and people.”

“Social media has given me a lot,” Alison adds, “but in a way only being an online presence makes me feel disconnected from the real world and I’m searching for something more tangible.”

She’s not kidding about this. “Currently I’m planning on moving to the desert and trying to figure out what I’d really actually like to do with my life, because I have no idea.”

The righteous path, it seems, is to let social media hold up your work for inspection and appreciation but not to let it change it. One’s heart should always be informing the work, not Likes and comments and follows.

“I mainly keep to myself on Instagram,” Sara concludes. “I don’t look to other contemporaries to see what I should be creating. I like to do what I want to do.”