While studying fine art in Johannesburg, painter Zandile Tshabalala was struck by the way art history would omit and marginalize Black women. Since then, she’s made it her mission to place them in the foreground of the frame, and to let their clothes, make-up and posture show the ease and strength that defines her vision of Black femininity. She tells Allyssia Alleyne how she hopes what started as a way to make herself feel more confident can now have the same impact on other women.

Zandile Tshabalala likes to keep her clothes where she can see them. Ferrying her laptop through her spacious Johannesburg studio – an artist’s dream with high ceilings, big windows and white walls – she turns its camera to the makeshift wardrobe she’s installed near the entrance. It is an overstuffed rail and wire drawers bursting with clothes, handbags and shoes. Busy prints, fur and iridescent sequins peek out between hanger after hanger of black.

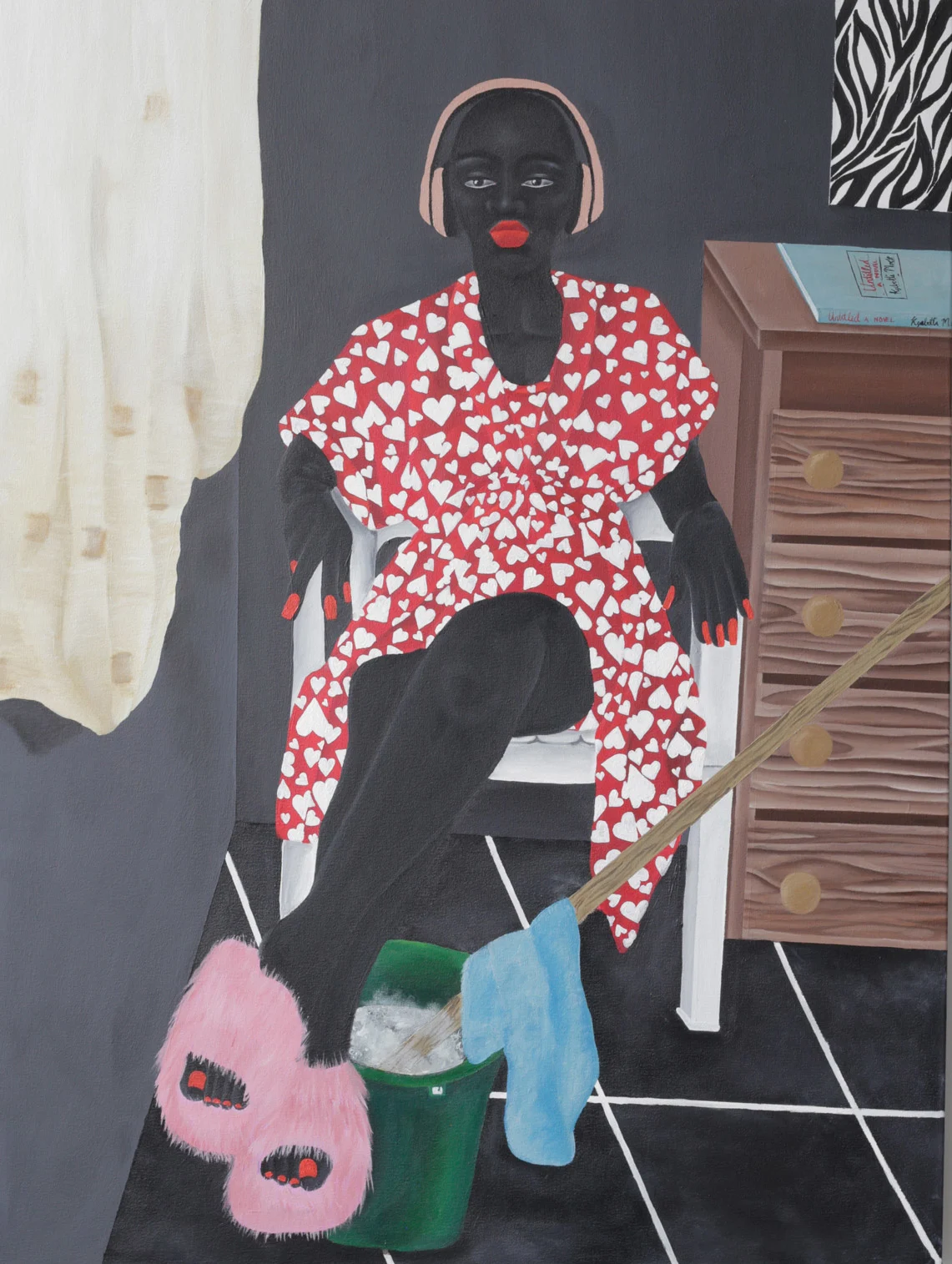

It seems a fitting set-up for a painter who, as a child growing up in Soweto, dreamed of a career in fashion rather than art, and customized her friends’ clothes for extra cash. Now 22, she dons pink ruffles, structured leather and statement earrings in her studio portraits. Zandile’s appreciation for the pleasures of dressing up seeps into her canvases. Her female figures – painted in flat, black licks of oil and acrylic – are dressed in leopard-print slips, clinging mini dresses, fur coats, orange pumps. Even when nude, they never feel truly naked, with crimson lips, fingernails and toes popping against dark skin.

“Some of the clothes are clothes that I actually have – I recently purchased a fur coat and was like, ‘It’s for a painting!’” she says. Occasionally, life imitates art too: It’s only after she made red lipstick an artistic signature that she started wearing it herself. “I like the work to have a very particular attitude and confidence, and I think works very well to achieve that.”

For Zandile, fashion and beauty are visual markers of an aspirational spirit of self-possessed Black femininity she’s made it her mission to capture. This spirit goes beyond appearance alone; it manifests in her figures’ direct gazes, and the ease with which they seem to inhabit their bodies, whether stretched across a sofa, sat next to a mop bucket, or posed against a leafy backdrop. “The attitude that I’m chasing in the work is being yourself without diluting anything – being whomever you desire to be and being unapologetic about it,” she says.

Zandile dates a turning point in her practice to late 2019, when, during the third year of her studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, she found herself searching out a visual vocabulary to help her come to grips with her own self-image and counteract the omission or marginalization of Black women in art history. She remembers being particularly struck during a lesson on Édouard Manet’s Olympia, where a nude white woman looks out at the viewer from the foreground, while her Black servant practically disappears into the drapes behind her.

The attitude that I’m chasing in the work is about being yourself without diluting anything – being whomever you desire to be and being unapologetic about it.

“That image and similar images made me realize that there was a pattern of Black women being placed in very specific positions if they were present, or else not being present at all,” she explains. “I wanted an image I could constantly go back to just to gather myself: an image of confidence and strength to encourage you to find joy and happiness in your space and within yourself.”

Zandile began using herself as her model and her surroundings as settings, moving the Black woman from the background to the fore while challenging existing standards around representation, beauty and desirability. Call it vanity; she’s unfazed. “Vanity, for a Black woman, is long overdue,” she says with a laugh and a shrug. “We’ve reserved so much of our time and effort for other people, so I don’t see why we shouldn’t in ourselves.”

Her current painting style is a melange of influences: Kerry James Marshall’s emphatically Black skin tones; the glamorous, powerful femininity celebrated by Mickalene Thomas; Henri Rousseau’s tropical dreamscapes; and Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s intimate domestic scenes. Zandile says she also looked to women who embodied the confidence she hoped to harness – Beyoncé and FKA Twigs, but also her own mum and grandmother – and channeled their energy into her depictions of beauty rituals, rest, leisure and undisturbed existence in nature.

Just interacting with other people, it seems that it’s an image that other women need as well.

“There is a bit of interest in the mundane, the everyday activities that you do in your own space to take care of yourself,” she says. “Those moments are just as important as those that are confrontational a comfort with the self.”

Zandile is in no rush to commit to her current style or thematics – there are still some months standing between her and her degree, after all, and she relishes the freedom to keep experimenting and evolving, venturing into new territory “when the time is right.” But being able to revel in and represent the beauty of Black femininity has been transformative.

“Making these works has played a great role in shifting my own confidence and self-esteem, and my ability to communicate my message,” she says. “Just interacting with other people, it seems that it’s an image that other women need as well.”