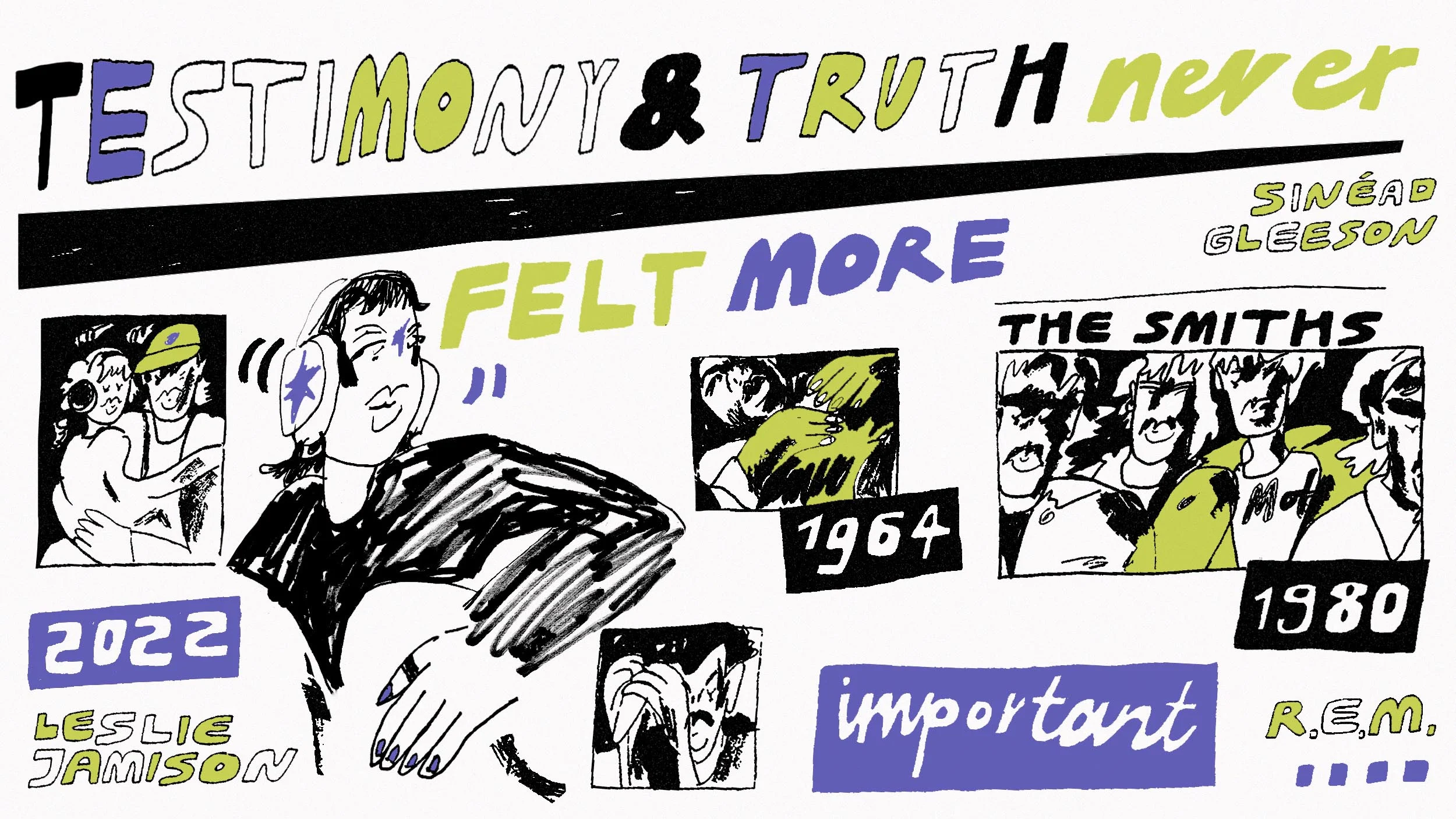

From a young age, Sinéad Gleeson took refuge in music. But as a music writer navigating the male-dominated industry in her twenties, she was painfully aware of the lack of female critics and journalists—and the hostility that seemed to follow what few female voices there were. With her new anthology “This Woman’s Work: Essays on Music,” co-edited with former Sonic Youth bassist Kim Gordon, Gleeson shares the mic with 16 women (including Maggie Nelson, Juliana Huxtable and Leslie Jamison) to rectify that imbalance. Here Sinéad explains why the process of collecting stories from women, what she learnt from the process, and why sharing them with the world is so important.

Illustrations by Luci Pina.

In the summer of 2019 on a hot, sweltering day, I found myself, of all places, inside a cinema. I wasn’t there to see a film, but to moderate a talk with Kim Gordon: musician, artist and ground-breaker.

I had seen Kim play with her former band Sonic Youth several times over the years, including twice one year apart when I was a teenager. The first show was in a venue where the crowd was sardined together, sweat dripping from the ceiling. The second gig had a support act I was keen to see, having bought their first album directly from Sub Pop in Seattle. Most of the crowd had never heard of Nirvana, but then this was a year before “Nevermind,” before global success, before Kurt Cobain’s tragic death.

Those same gig years were blighted by illness and immobility. A lot of my time was spent bedbound, or in hospital, with the dual axis of books and music to keep me sane. I could drown out the ward’s constant soundtrack of beeps and footsteps with a Walkman; or imagine myself somewhere—anywhere—else, thanks to the geography of each book I stepped into.

Women may have been edged out of historical timelines, but we gain so much when we bring them back out for an encore.

In my early twenties, I figured that it was possible to turn a hobby and the things you love into a job. I wrote about music, interviewed singers and reviewed gigs. It was all I knew and loved. What I didn’t love was the need to justify all I came to know about it. When I started reviewing music for a national newspaper, I was frequently grilled—only ever by men—about why I preferred one album over another, why three stars were awarded instead of four, why I had compared the influences of one band to an earlier act. “Why?”, in that particularly sneering tone, was the “Well, actually…” of the day.

A few years into that music journalism career, I interviewed Kim Gordon about her memoir, “Girl in a Band.” The title holds its own irony, but summed up the experience of so many of my female friends who played music, and demonstrated to those of us who were fans or writers how male the industry gatekeepers were, from A&R to managers, sound engineers to music magazine editors. Growing up, I’d seen only a handful of women writing about music in Ireland. The internet has helped democratize whose voices are heard, but given the gains made, it feels more important than ever to have women not only writing about music, but also running record labels and booking major music festivals. And we need to make sure that all kinds of women are included, or we risk excluding marginalized voices.

That cinema meeting happened because Kim was in town for the opening of “She Bites Her Tender Mind,” an exhibition of her art. (Long before Sonic Youth, Kim went to art college, as so many musicians did.) In my introduction, I spoke about what a figurehead Kim was for women who liked music, but especially for my female friends who were in bands. The conversation weaved in and out of inequality, the sense that we need new narratives, and broader voices speaking up.

The following day Kim went to London to meet the editor who had commissioned “Girl In A Band,” and he asked if she’d like to edit an anthology of essays about women in music. She said yes, but only if she had a co-editor, and mentioned that she’d just been interviewed by a writer in Dublin, who loved music, had previously edited anthologies before and had gotten on well with. It was a fluke, or fate. And without that luck, or the planets lining up, there’s a good chance that “This Woman’s Work: Essays on Music” may not have happened.

Music was all I knew and loved. What I didn’t love was the need to justify all I came to know about it.

Canonical music books have a tendency towards hagiography and chronology; books that pivot on gossipy reveals or deconstructed deep dives into how the music was made. From the start, Kim and I knew we wanted something else. After gathering a wishlist of writers, we decided against giving them each a strict brief, and instead invited them to write about a subject that meant a lot to them, or that they had a lot to say about. A blank page offers possibility, but such an unfettered remit can be terrifying for an editor: will the piece be too broad? Too niche? Not what we’re looking for? We took a leap.

It paid off: even when the submitted essays were about familiar names or subjects, each one taught us something new or alerted us to some truth we’d forgotten.

Juliana Huxtable’s piece is a “praise poem” for the singer Linda Sharrock, a Philadelphia-born jazz singer who had worked with Pharoah Sanders in the 1960s. On her seminal 1969 album “Black Woman,” produced in collaboration with her musician husband Sonny, Sharrock’s voice is outside of language, bending notes in exploration of ecstasy. For Huxtable, Sharrock’s work represents black female experience, sex, and the possibilities of expression. When I listened, it was a reminder that music is rooted in the body; that rhythm and sound are buried in our cells.

There’s a similar echo of mortality in Maggie Nelson’s writing about her musician friend Lhasa de Sela—a rising star in world music before her death from cancer at 37. The essay is a memento mori as much as a lament; a metronome hint that life is always counting down, and we should make it count.

Music has its elevated, public joys and deeply, private sorrows, but it can also be political and subversive. Fatima Bhutto, niece of Pakistan’s former leader Benazir Bhutto, was born in Kabul, but moved peripatetically with her father, who was in political exile. She writes of how music both reminded her father of his homeland, and was a source of sedition for those who spoke out against the regime. Similarly, Chinese-American writer Yiyun Li notes the power of propaganda in Chinese anthems, which she sings on a cross-country car trip to stay awake, aware that she had once rebelled against these very songs.

We need to make sure that all kinds of women are included, or we risk excluding marginalized voices.

Leslie Jamison documents how her brothers and boyfriends influenced her musical taste, until finally realizing that it was the music introduced by her two queer aunts that left the most an indelible mark. It made me think of my own early influences – my father, who played nights in a band to make extra cash, introduced me to Roy Cooder, Stevie Wonder and Talking Heads; while my guitar-playing older brother indoctrinated me into The Smiths, REM and countless jangly guitar bands through repetition and thin bedroom walls.

Indeed, there is something about the culture we discover when young that never leaves us. The watermark remains, like Proust’s madeleine, linking back to memories, moments, people. There are many mentors throughout the book: Ella Fitzgerald showed Margo Jefferson the ways of Black womanhood; while Ottessa Moshfegh’s violin teacher, Valentina, taught her that she had “the capacity to feel and to think and make, and to move others with what I make.”

When it came to write my own essay, I was faced with the tyranny of choice. There were so many women I could have chosen, and in the end it was lockdown that presented my subject. Wendy Carlos, was a composer and pioneer of synthesized music, working with Bob Moog on the development of his Moog synths. In lockdown, my husband and I listened to the ululating, eerie track she composed to open “The Shining.” It suited the mood of isolation (a writer holed up with his family, unable to go anywhere) and the sense of fear that Covid brought. It struck me, again, how music finds ways to exclude women, or not pay them their due. Carlos should be as well known as John Barry or Delia Derbyshire.

What’s at the heart of the book is the realization that there are so many musical stories that I – we, you – don’t know yet.

An essay is never about a single subject, no matter how hard it tries to be, or persuades a reader that it is. There are multitudes and mirrorings in “This Woman’s Work” many accidental, welcome overlaps. What’s at the heart of the book is the realization that there are so many musical stories that I—we, you—don’t know yet.

Bringing these stories to light makes us more willing to look beyond the big names and curated playlists to the lost voices. Women may have been edged out of historical timelines, but we gain so much when we bring them back out for an encore.