Dancehall was born in Jamaica in the 1970s, but its rhythms have spread around the globe in the decades since, with energetic events taking place across Canada, the US, the UK, Japan and beyond. In “Art of Dancehall,” Walshy Fire and his community of archivists, experts and collectors trace the evolution of the culture, via the event posters that drew fans in as its sound traveled from Kingston to the world. Here, Walshy and a host of other contributors tell Nicolas-Tyrell Scott about their love for the visual culture of dancehall, and highlight the legacy of the earliest design trailblazer of the field, the late Sassafrass.

You can purchase Art of Dancehall here.

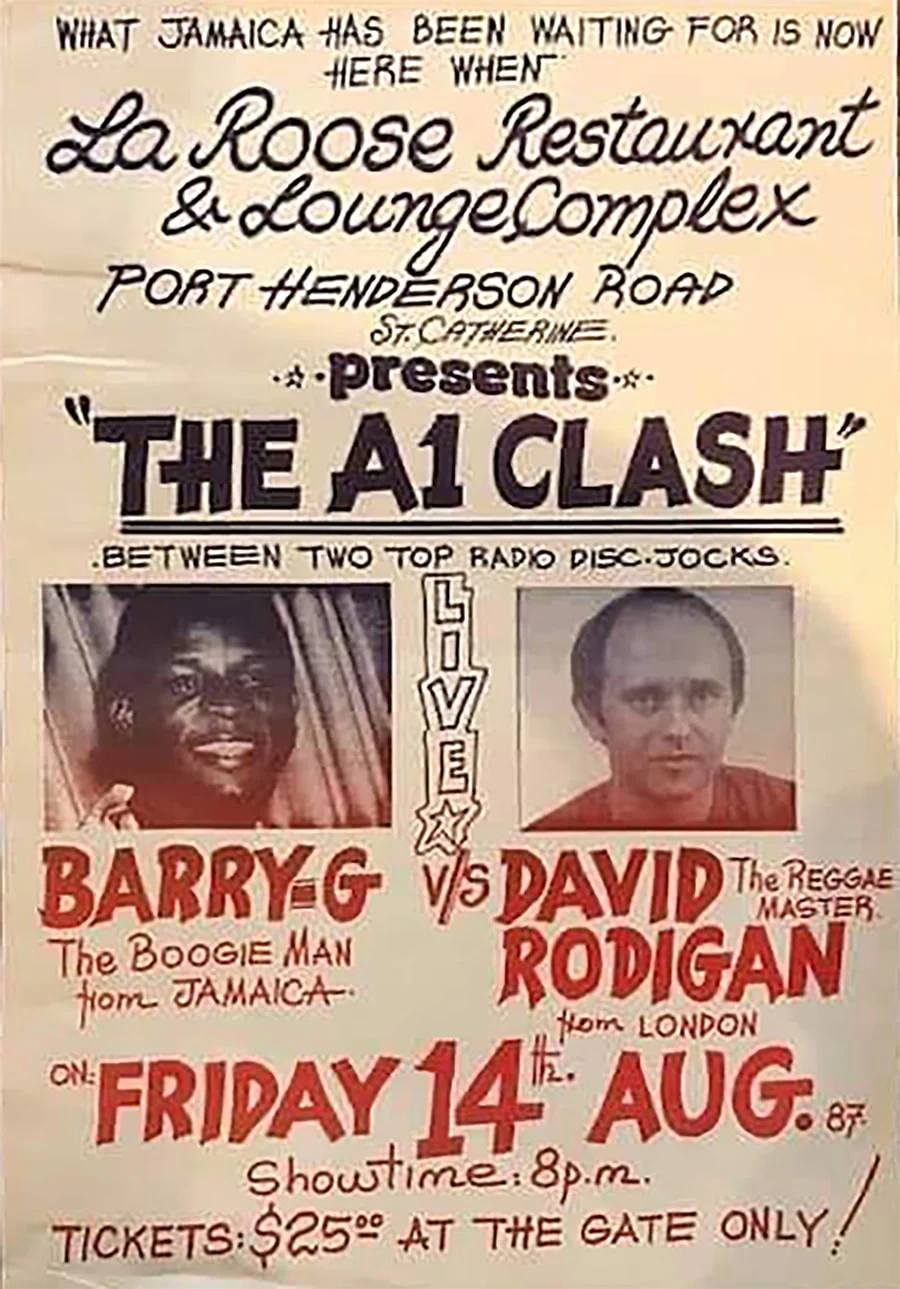

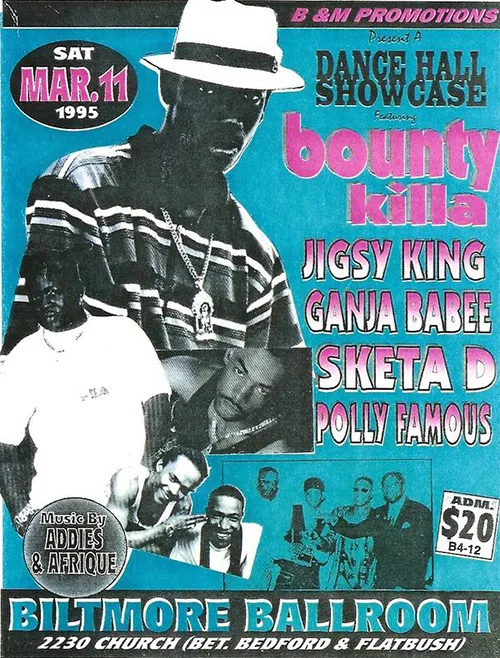

Years before his role as MC of Major Lazer, or as a soloist, Floridian native Walshy Fire would traverse many a soundclash, from the origins of the culture in Jamaica to those run in Miami, New York and London. “One time, I went to a Killamanjaro versus David Rodigan clash at Mahi Temple, and Bounty Killer came out,” he recalls. “He performed as a surprise guest for one of their sets and as soon as he stepped out, gunshots ran everywhere.” “Gun shots,” in this context, doesn’t signify violence, but endearment. Dancehall, which soundclash culture grew with, facilitated this eternal form of jubilance—the riddim, the tempo, the artists, MCs and/or DJs, the attitude, flair and ultimately the wickedest dubs being the name of the game, enthralling listeners in real time.

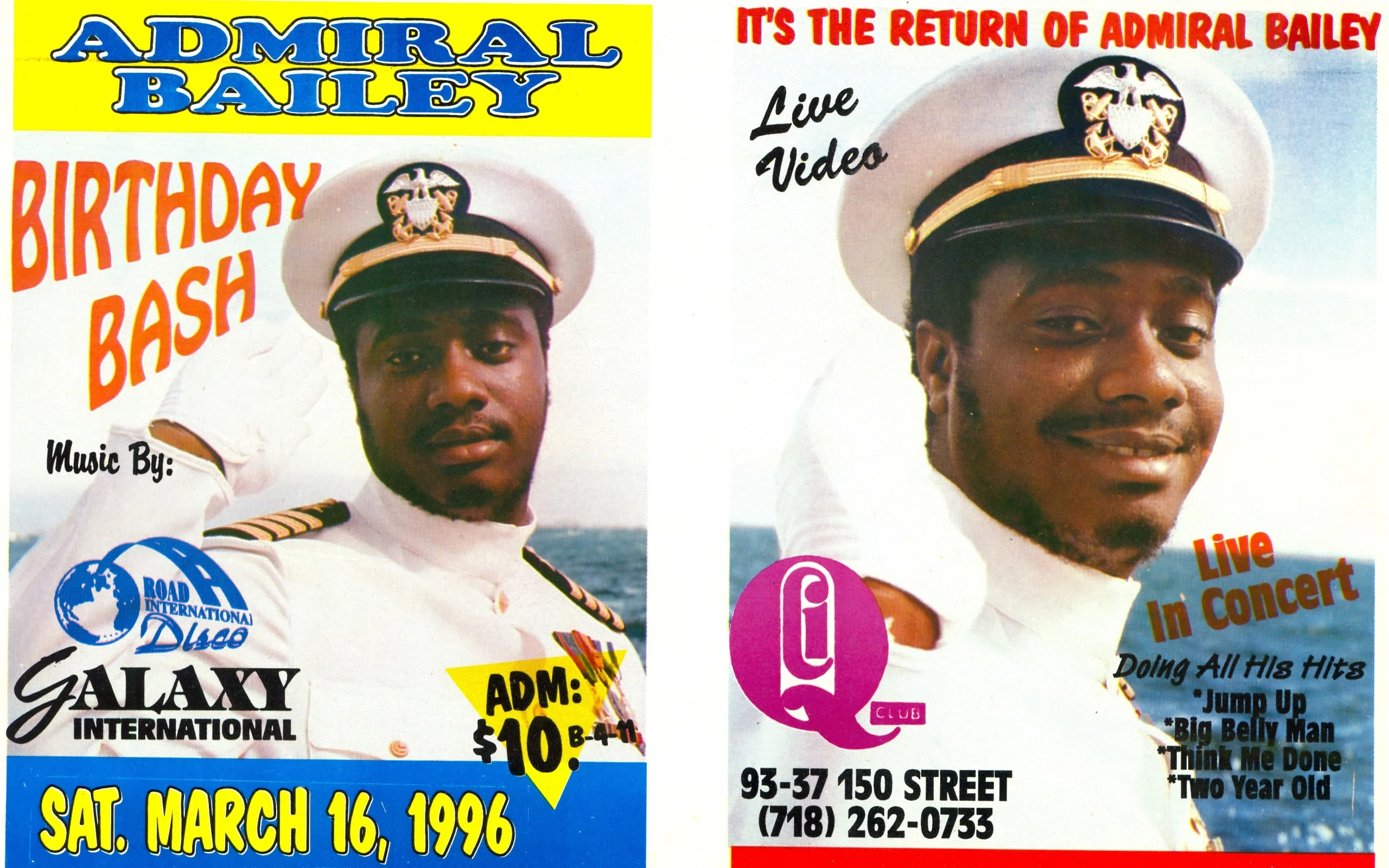

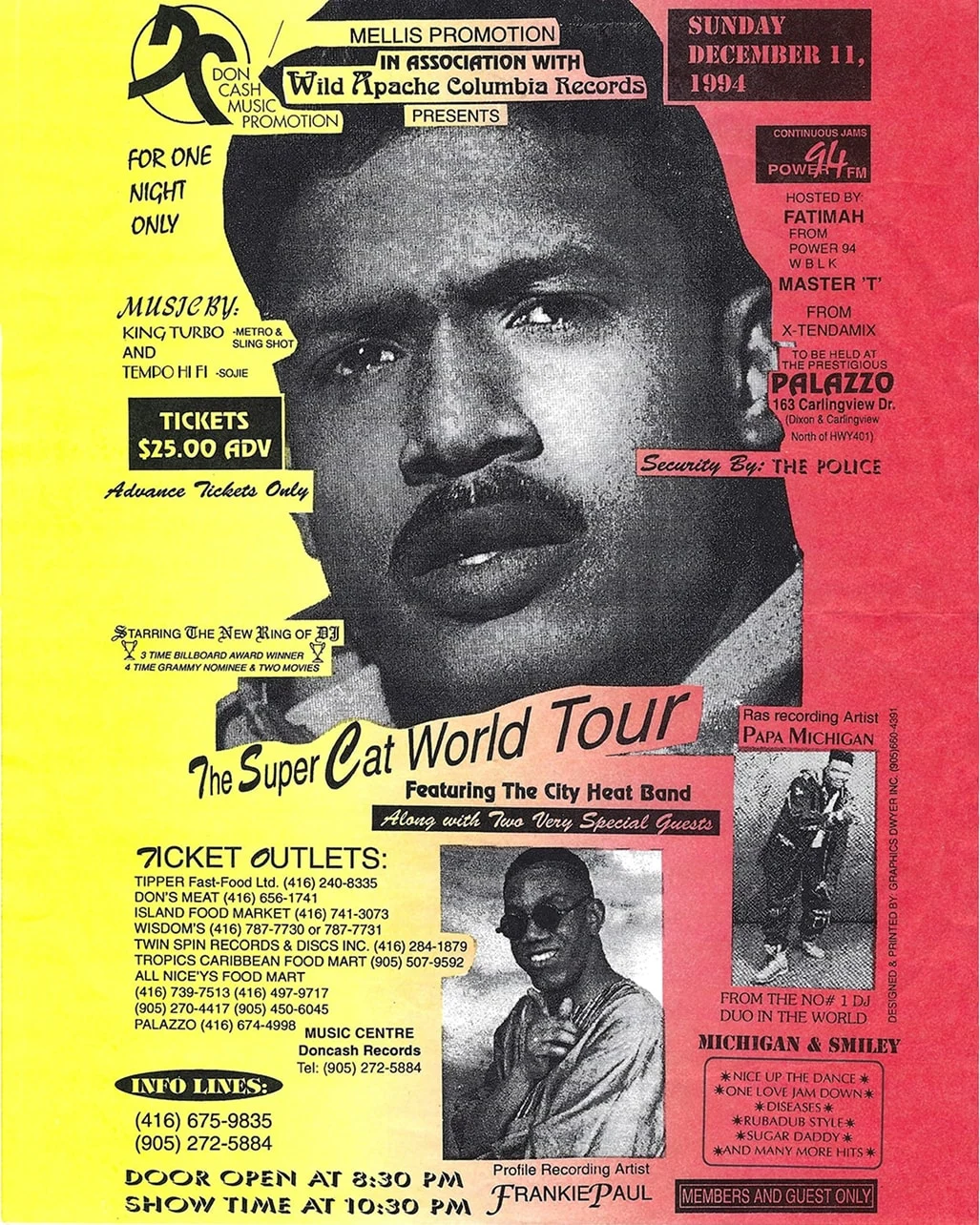

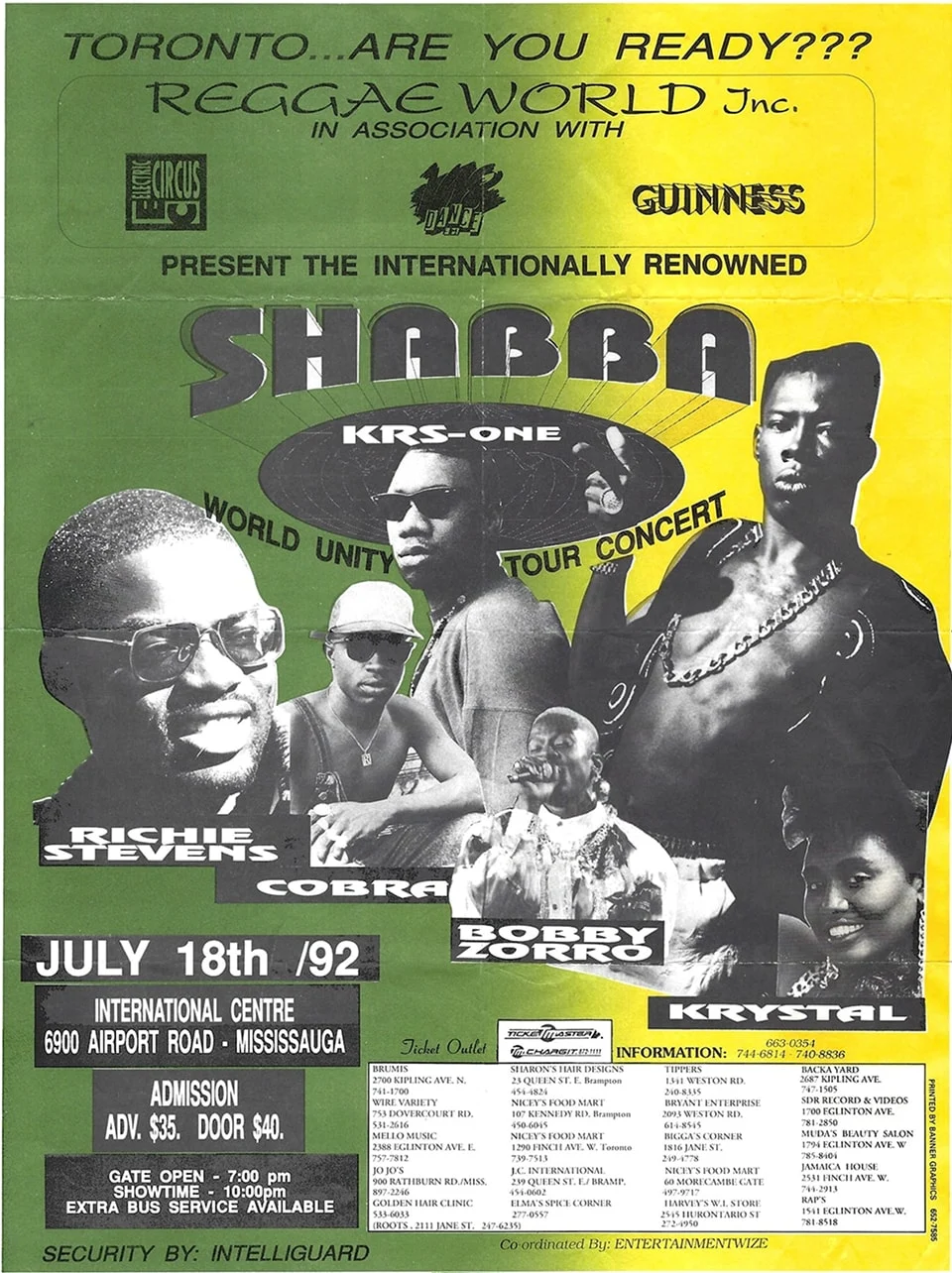

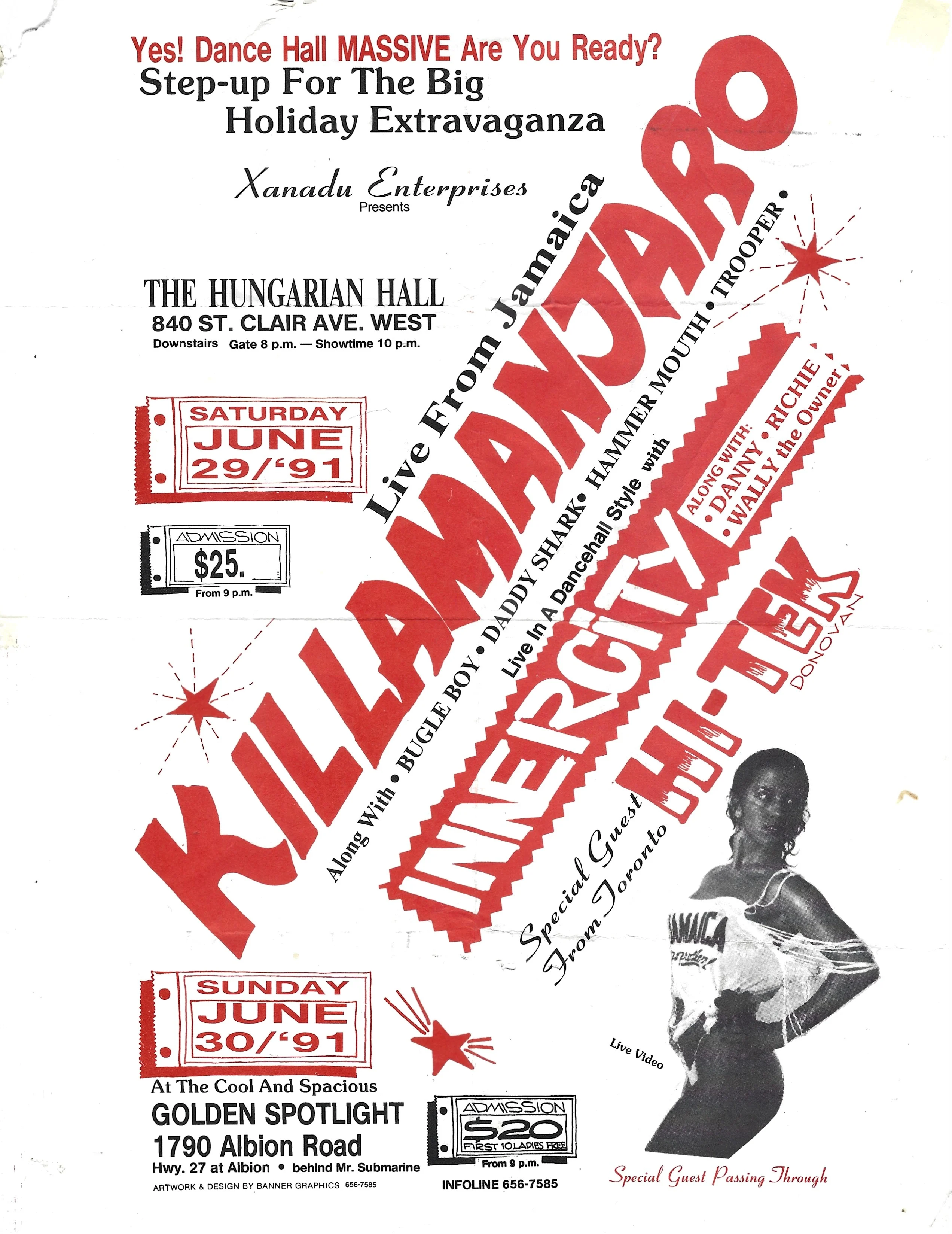

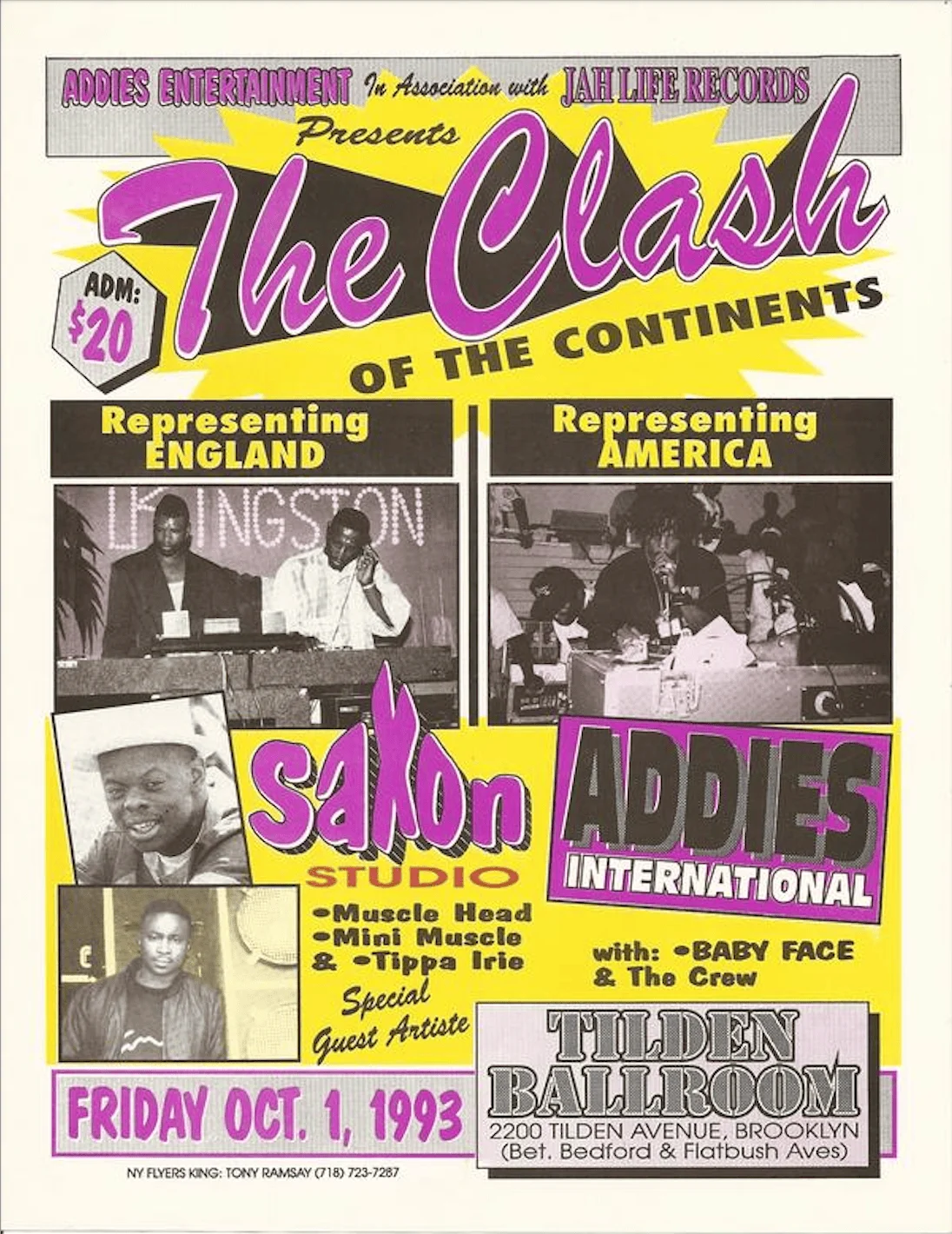

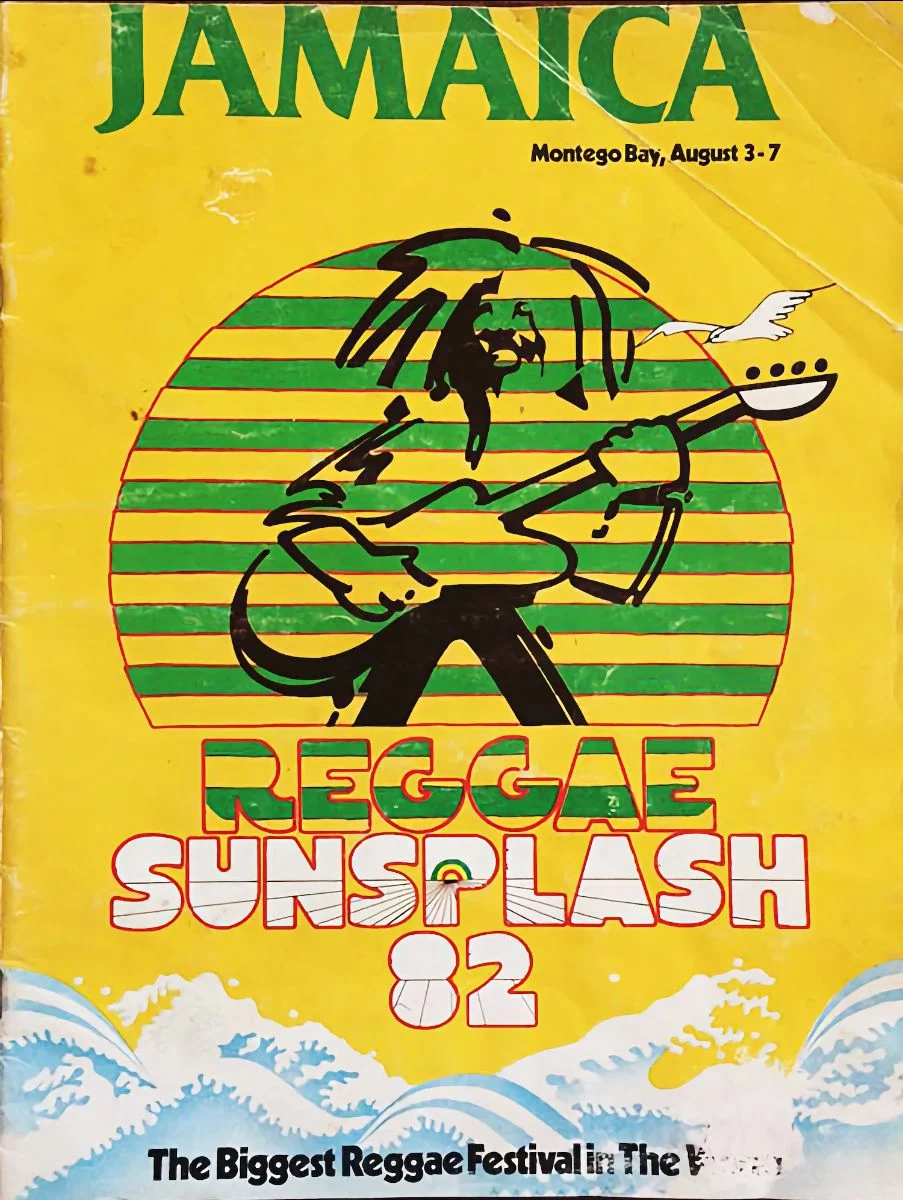

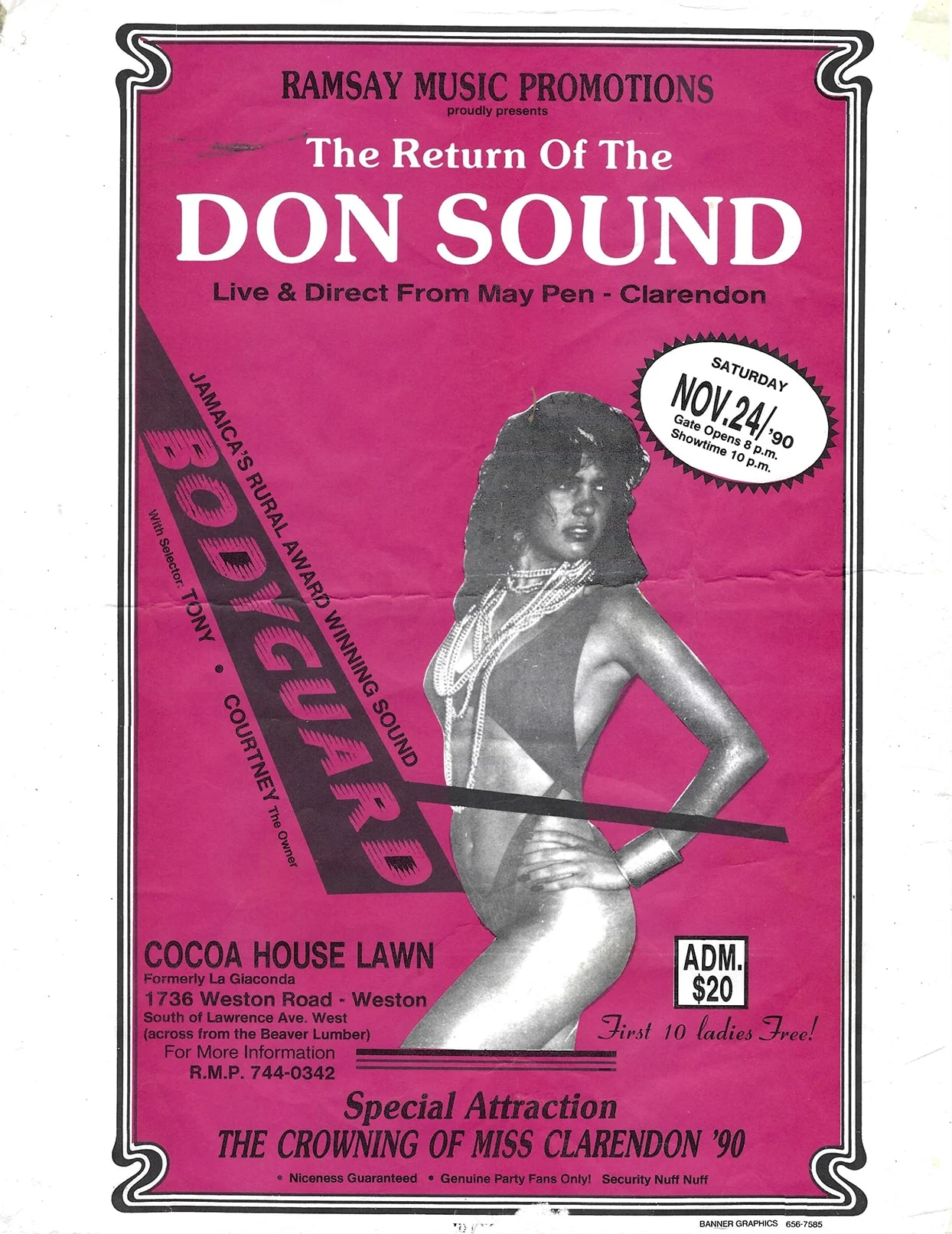

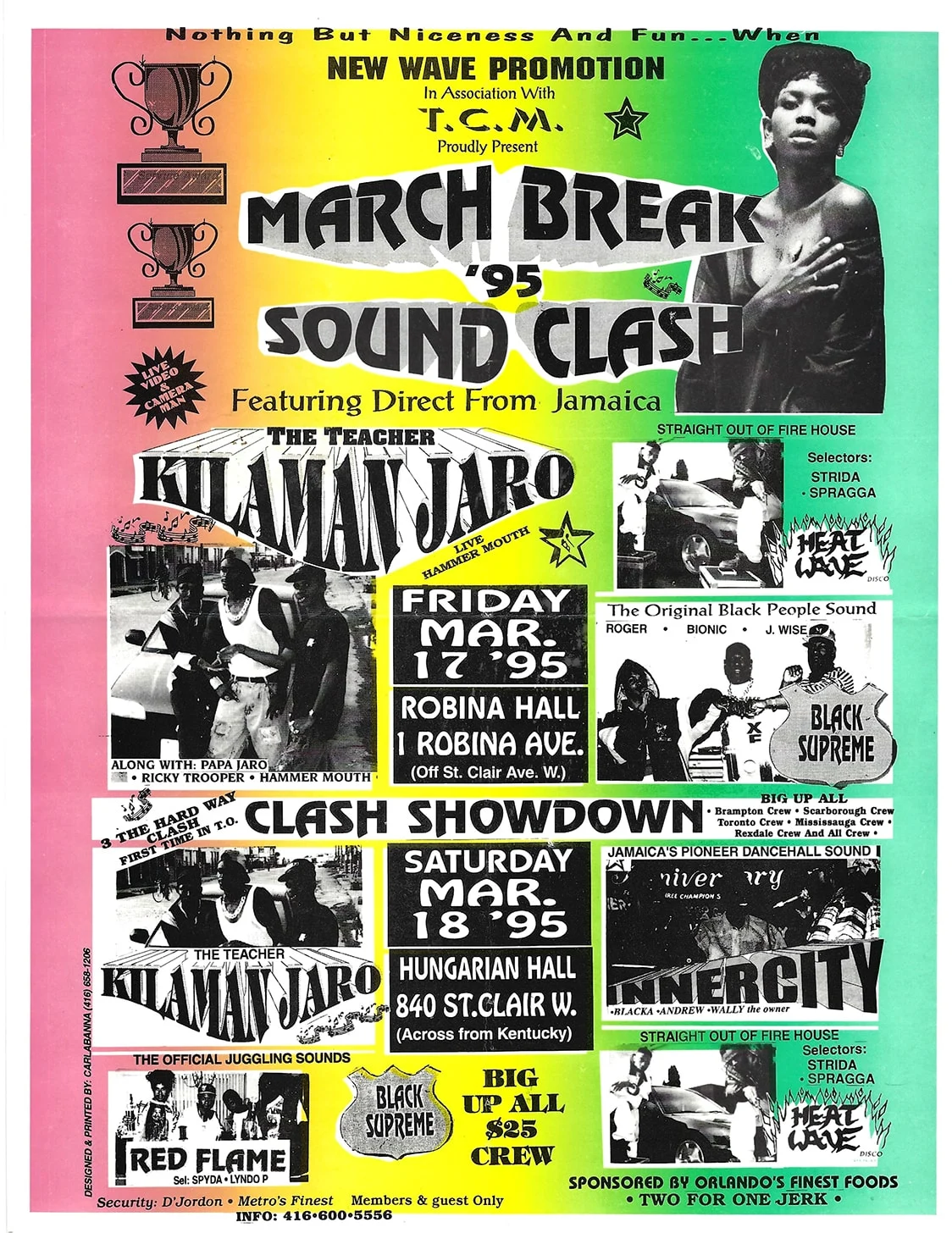

Now, Walshy’s book, “Art of Dancehall,” acts as a tangible archive of the history of dancehall—and by proxy, reggae—via the posters that drew fans to the events around the world. The publication spotlights the who, what and where of the culture, displaying prolific sound systems including Killamanjaro, figures like Madoo and venues like Carib Continental Club.

The now veteran DJ and presenter David Rodigan appears across multiple chapters of the book, the first of which serves as an announcement for his “A1 Clash” against Barry G in 1987 in Jamaica. The collection of posters from Jamaica act as one of the most playful of all regions featured, the odes to wrestling advertisements prominent across this clash poster specifically. Even in the language used—“showtime,” “v/s”—dancehall and reggae lovers’ excitement was nurtured. The posters and their iconography would informally enthrall those old enough to attend, while making kids eager to catch a glimpse of the festivities.

Early Jah Love Muzik advertisements would call attention to the island’s strong ties to religion, specifically Rastafari convention, with Bible quotes at the top of each poster—a poignant note of the times and a distinct marker in this segment of Jamaica’s roots reggae posters. 1984’s Children of Emperor’s Ball references God living in Ethiopia’s former emperor Haile Selassie through its green formal font featured at the top of an invigorating poster. His visit to Jamaica in 1966 is considered quintessential in modern Rastafarianism, acting as an event that mobilized and re-energized the movement.

Walshy enlisted a whole host of contacts to contribute posters and expertise to the book, among them Toronto-based dancehall enthusiast, podcaster and archivist Sheldon “Muscle” Bruce and DJ, archivist and vinyl collector Mark Professor, as well as fellow collectors Lee Major DeBoss and StranJah. He also reached out to the dancehall and reggae communities he has stayed close to for years, asking for posters, and began building a collection. “It was easy, but hard to do,” Walshy says. “Everyone has bits and pieces, but doesn’t realize how valuable that is to the documentation—it’s been a communal effort.”

“I was 12 or 13 when I saw my first poster,” says Muscle. “My sister’s boyfriend bought a poster back from London for me.” Immediately fascinated, Muscle became immersed in the dancehall community surrounding him in 1980s Toronto. “I’d see that a few of them were happening in Scarborough specifically,” he adds. Dancehall began a decade prior to Muscle’s introduction to it at the turn of the 1970s, with records formally produced and recorded for the first time by the mid-1970s thanks to the likes of Henry “Junjo” Lawes.

At 14, Muscle attended his first dancehall event. “I think this was 1988,” he says, laughing. He got to witness a prominent sound system of the time, Renegade, playing every Friday and Saturday night locally. Muscle would witness toasters like Gregory Culture, Selector Chicken George and more rap alongside dancehall productions.

In London, dancehall had found in-roads, too, thanks to the West Indian diaspora, including Jamaicans, who had migrated from the 1950s onwards to the British capital, as well as cities like Toronto and New York. Constantly in touch with their homelands, their mother tongue and other cultural artefacts would follow them. After all, “Jamaica was always the hub of dancehall,” as Muscle explains.

Mark Professor remembers the expansion of dancehall in London, and the clashing culture that followed. “1981, 82, you’re beginning to really see this whole dancehall phenomenon take over here,” he recalls. Pointing to prolific figures like Yellowman, Mark remembers beginning to buy records on British soil. “Brigadier Jerry, Gemini Sound System, you’d hear them all then.” Mark, who was immersed in the scene, sees Brigadier Jerry’s “Pain” as a seminal record. Records and soundclash recordings, like posters, allowed for the Caribbean diaspora to follow dancehall, and contribute to its migration to other parts of the world as they consumed it.

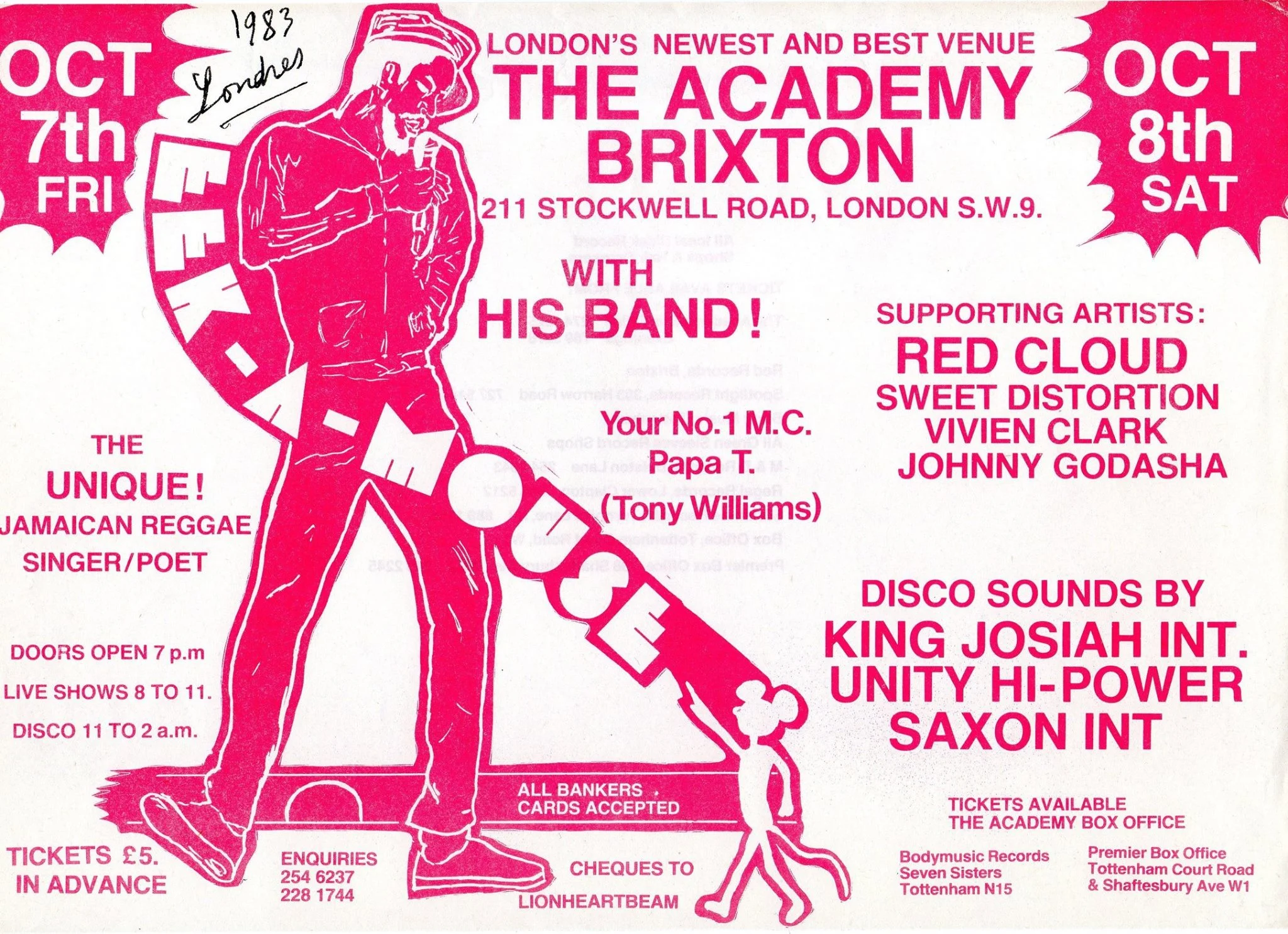

1983’s Eek-A-Mouse poster shows the Jamaican titan boldly, explosions atop the right and left hand side corners with pink capital letters describing him as “UNIQUE!.” It departs from the usual UK aesthetic, in its more playful presentation of event details.

“Sometimes, promoters could play with conventions,” Mark adds. “But the UK did have that simplistic form of presentation at first.” Eek-A-Mouse’s poster is also a sign of the birth and growth of London’s event spaces—in this case, Brixton’s now prolific Academy, platformed as the “newest” and “best” spot in luminous hot pink text. “So many venues are gone now, I check all the time,” Mark continues. “The ones we do have left are a blessing.”

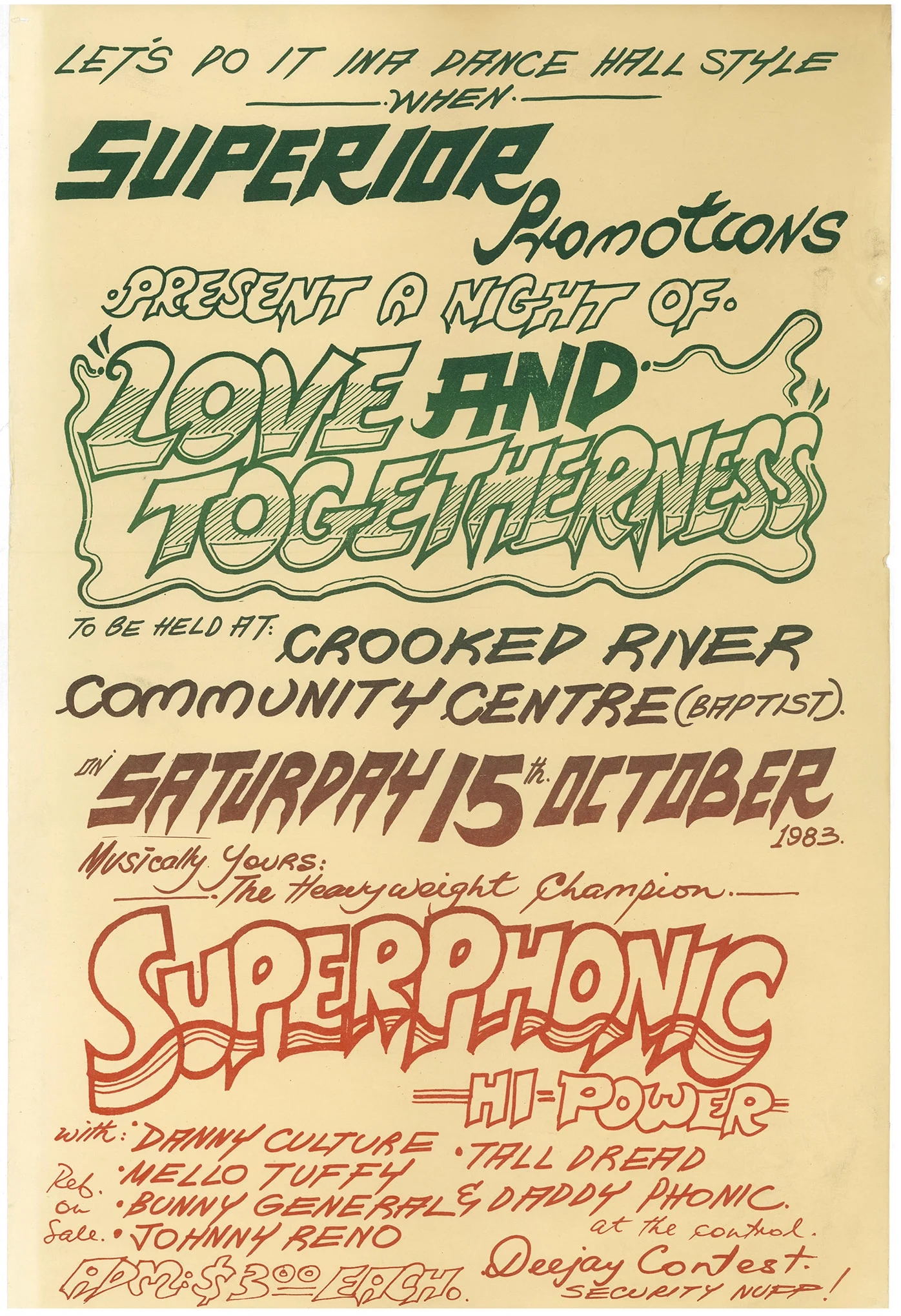

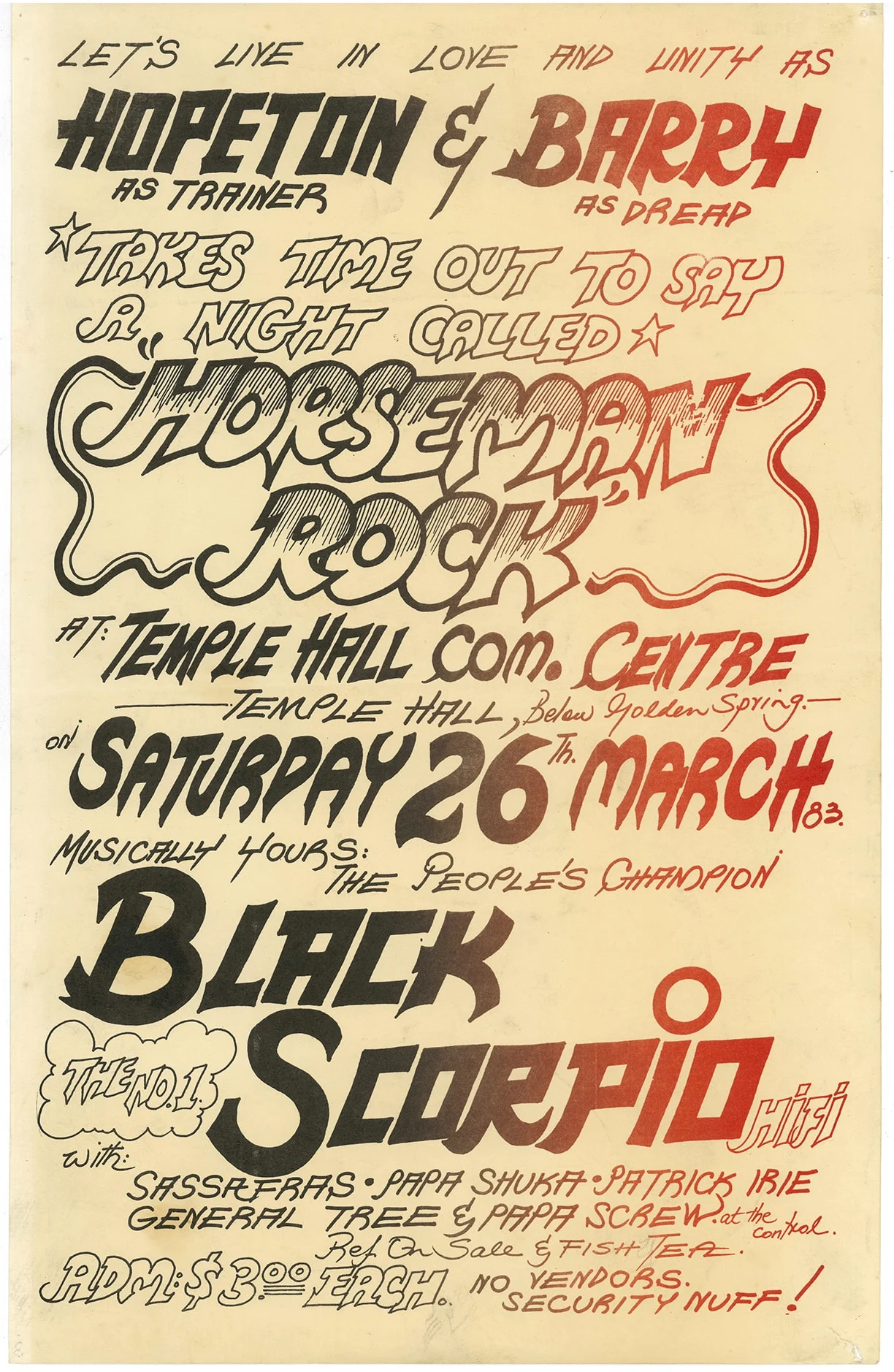

Split across Canada, the US, the UK and Japan, “Art of Dancehall” showcases stylistic references and notes across each region. It highlights the documentation of dancehall and reggae festivities as both grew across the world. From London’s typography mirroring that of newspaper designs at times, to New York taking influence from hip-hop’s DIY posters, each region had specific cultural markers that uniquely influenced the design principles of their posters.

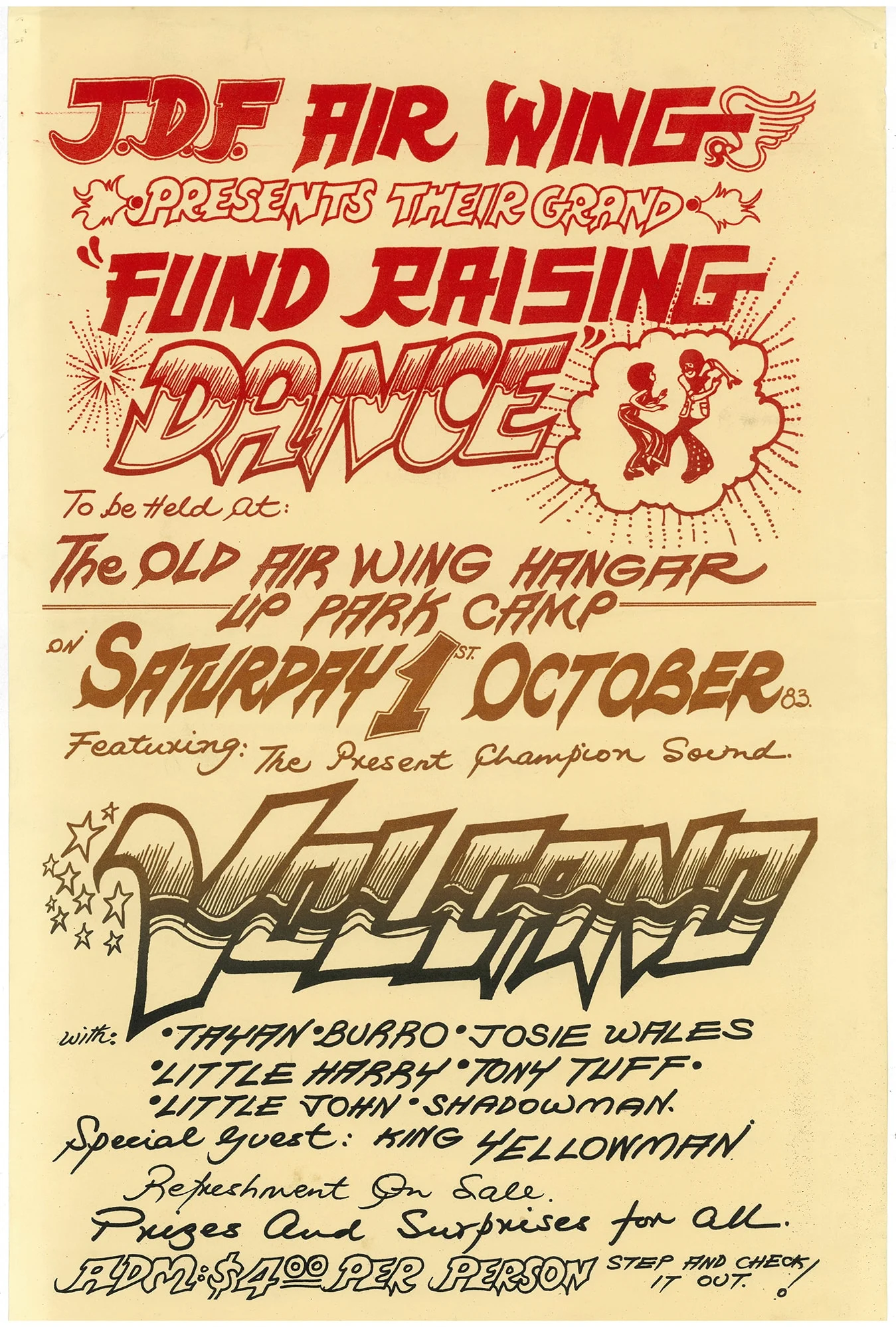

Some of the most significant designs shown in the book belong to Jamaican dancehall graphic artist Sassafrass, or Denzil Naar. Going by the names “the mechanic” and “the technician,” he became a cult Jamaican figure in dancehall poster design. His signature sharper take on bubble writing—often using graphics and stencil designs for each individual letter—became renowned across the island and wider Caribbean region as the 1980s and 1990s progressed.

“I kind of see Sassafrass as the first Jamaican graffiti writer, so to speak,” StranJah says. “As a [graphic] artist attacks his blackbook, Sassa attacks his blank page.” Having procured a lot of the Jamaican posters for “Art of Dancehall,” StranJah believes a lot of the references likely came from comic strips and magazines. When color bleeding arrived across the design sphere in the early 1980s, Sassafrass’ designs soared, becoming even more animated, with the red to blue bleeds he would infuse into his work.

1983’s advertisement for Metro Posse at the Tropics Club is a perfect case in point. Able to communicate the groove of dancehall through the text’s curves, bubbles and waves, the poster is an epitome of Sassafrass’ design principles. Tragically, Walshy had been in talks with the designer about designing the “Art of Dancehall” cover when he passed away in 2022. From recent Protoje single artworks to Mr Vegas’ “Sweet Jamaica” album cover art, the cultural odes to Sassafrass’ aesthetic are deeply entrenched in popular dancehall culture.

Like the legacy of Sassafrass, Walshy Fire believes that cultural preservation of dancehall is key. “Art of Dancehall” acts as his and the wider dancehall community’s tribute to, and celebration of, the culture’s lineage. “Dancehall’s always found a way to keep going,” he says, “to move people.”