In many ways, the art world is more inclusive than ever, with artists and audiences of different backgrounds given more access and opportunity to engage. Yet its exclusive private members’ clubs, funded and frequented by elites, show no signs of slowing down—and with countries facing crippling cuts to public arts funding, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Here, London-based critic and curator Rianna Jade Parker reflects on her own first-hand experience of the clubs in the UK, and muses on the value of these kinds of rarefied spaces in general.

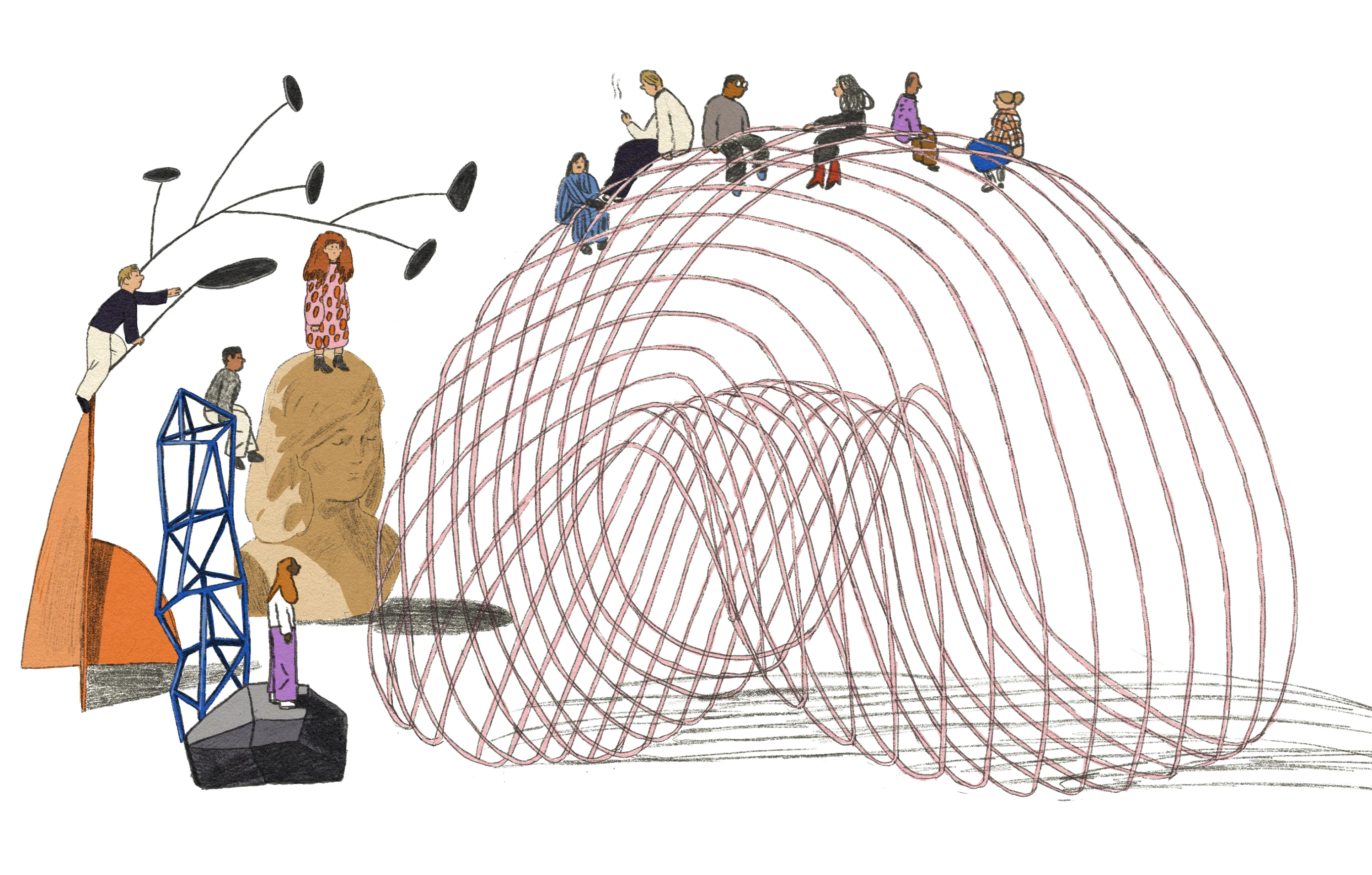

Illustrations by Karlotta Freier.

Today, the argument is not simply whether the arts are virtuous and intrinsically valuable to individuals, communities and society as a whole, but whether it is still too virtuous for everyday people. We now confidently assume the right to be in contemporary art spaces, public and commercial, and to enjoy meaningful art experiences and peer-to-peer expressions of thoughts and feelings. Any barriers of access faced by the working class are largely practical, not perceptual.

But exclusivity has always fueled this industry, in part justifying the loose regulation of the art market and the promotion of lavish, Instagram-ready social lives; and most participants and audiences, younger and older, aren’t explicitly concerned with art’s monetary worth. Instead, its significance is measured through its social currency, timeliness, and relatability. The high esteem and cultural value associated with belonging to this conglomerate widely understood as the art world is measurable and desirable, and so the stakes are high.

With less governmental support for artistic lives, the responsibility or concern falls on individuals and small groups.

The art world makes strong strides with unexpected profits, despite a global pandemic, while simultaneously, arts education in the UK is being stalled. The true scale of the current Conservative government’s misminded and unscrutinised public spending is yet to be felt, but the fiscal squeeze and sustained attack through defunding is going to cause some permanent shifts in the arts, especially as it pertains to already marginalized groups of young people.

Last year, the Conservative government announced plans to save £20 million ($22.5 million) by cutting funding for art and design courses in universities and colleges by 50% across higher education institutions which will affect 13 subject areas, including art, design, music, and media studies. But 16 “small and specialist institutions,” including the prestigious Courtauld Institute of Art and the Royal College of Art in London, will receive nearly five times their usual funding, thus cushioning the elites and the preferred from the fall-out.

With less governmental support for artistic lives, the responsibility or concern falls on individuals and small groups. But with private money comes private interests.

In August 2022 it was announced that the above-exclusive 37-year-old Groucho Club in London’s Soho was acquired by the owners of the blue-chip Hauser & Wirth gallery for £40 million ($45.2 million) through their hospitality company, Artfarm. At the time, Ewan Venters, CEO for both ventures, said that “under Artfarm’s ownership, the future of the club is assured. We will respect the history and traditions of the club, and we look forward to engaging with its membership to create a long-term future for the Groucho that builds on its eclectic appeal and maverick ethos.”

What is the appeal and ethos of a private members’ club with 5,000 members, a 150-strong art collection, and a supplementary function as a private bar Turner Prize winners? What exactly is behind these closed doors? If you’re willing to pay, you can find out.

This is a reflection of the deepest stage of communally committed individualism we’ve seen in a generation. But it’s not the most morally debased exchange to exist in the art world, nor is the Groucho unique in its exclusivity. The original Soho House (£1,100 per year + £550 joining fee), 180 The Strand (£100 a month) and late-night events at Annabel’s (£3,250 per year + £1,750 joining fee) and The Ivy won’t be going out of style soon; and I’ve enjoyed breakfast at the Chelsea Arts Club (£688 per year) with Winston Branch, one of the last living members of the 1950s Caribbean Artist Movement in the UK, whose 30-year membership to a club never meant to include Black migrants is a marker of pride.

What exactly is behind these closed doors? If you’re willing to pay, you can find out.

Similar fractions of exclusivity, to very different outcomes, exist amongst artists too. The Bloomsbury Group, the Young British Artists, the Blk Art Group, Guerilla Girls—these are otherwise known as collectives and go mostly unchallenged. The genesis of such spaces was less to do with promoting a public interest in the arts, than responding to periods of intense social change and artistic experimentation, which required transformative cultural institutions.

Ten years ago, I belonged to a collective, the Lonely Londoners. We staged exhibitions in London and New York using our own money and resources extended to us by good people. This activity would attract the attention of higher-ups, and I was later invited to join Tate Collective (now known as Tate Collective Producers): a group of under-25s with a £5000 budget to produce quarterly after-hours programming responding to Tate exhibitions and displays. Recruitment came predominantly from local schools and alternative art programs, and I believe it was because of this limited access to the preferred art school students that, during my tenure, Tate Collective was a largely working-class and multi-ethnic group of young people.

Arts employment charity the Creative Society was introduced in one of our monthly meetings. It was open then to people under-26 living in Lambeth or Southwark who were unwaged, or being paid less than the London Living Wage—a sad catchment that worked in my favor. The Creative Society helped to sustain my access to a quality artistic practice, both as audience and participant, with free tickets to live events and exhibitions, job fairs and formal mentorship. Forever having to adapt its scope to match unstable funding, it aligns with cultural organizations that want to establish functional relationships with young people and communities, and those that prioritize paid work within the arts and across wider sectors.

It was, in fact, the founder of the Creative Society, Martin Bright, who first made the unlikely connection between myself and Frieze magazine. In 2018, after stiff encouragement, I applied for the Frieze publishing traineeship and today, I sit on its masthead as a contributing editor. Like many others, I have and will continue to advance professionally and personally through a cocktail of selectivity, influence and just dues.

It may read as hyperbolic, but I gained more critical thinking, observation, appreciation and self expression from the best members’ club in the world, Tumblr, than I did during my MA at Goldsmiths, University of London. This free, lateral and informal education on aesthetics and art history was boundless. It established a visual literacy and taste that you can’t buy or borrow, evidenced in past Tumblr-residents such as writer-curator Kimberly Drew, conceptual artist Martine Syms and photographer Tyler Mitchell—all of whom are no doubt now members of prestigious clubs worldwide.

These alignments are not necessary to shun or aspire to; and it’s futile to tie your self-esteem and value as an artist from formal memberships and media visibility, rather than your own passions and grassroots initiatives with peers. There is no club that can instill a lasting consciousness around your practice and the spirit of comradery needed to survive as an artist.