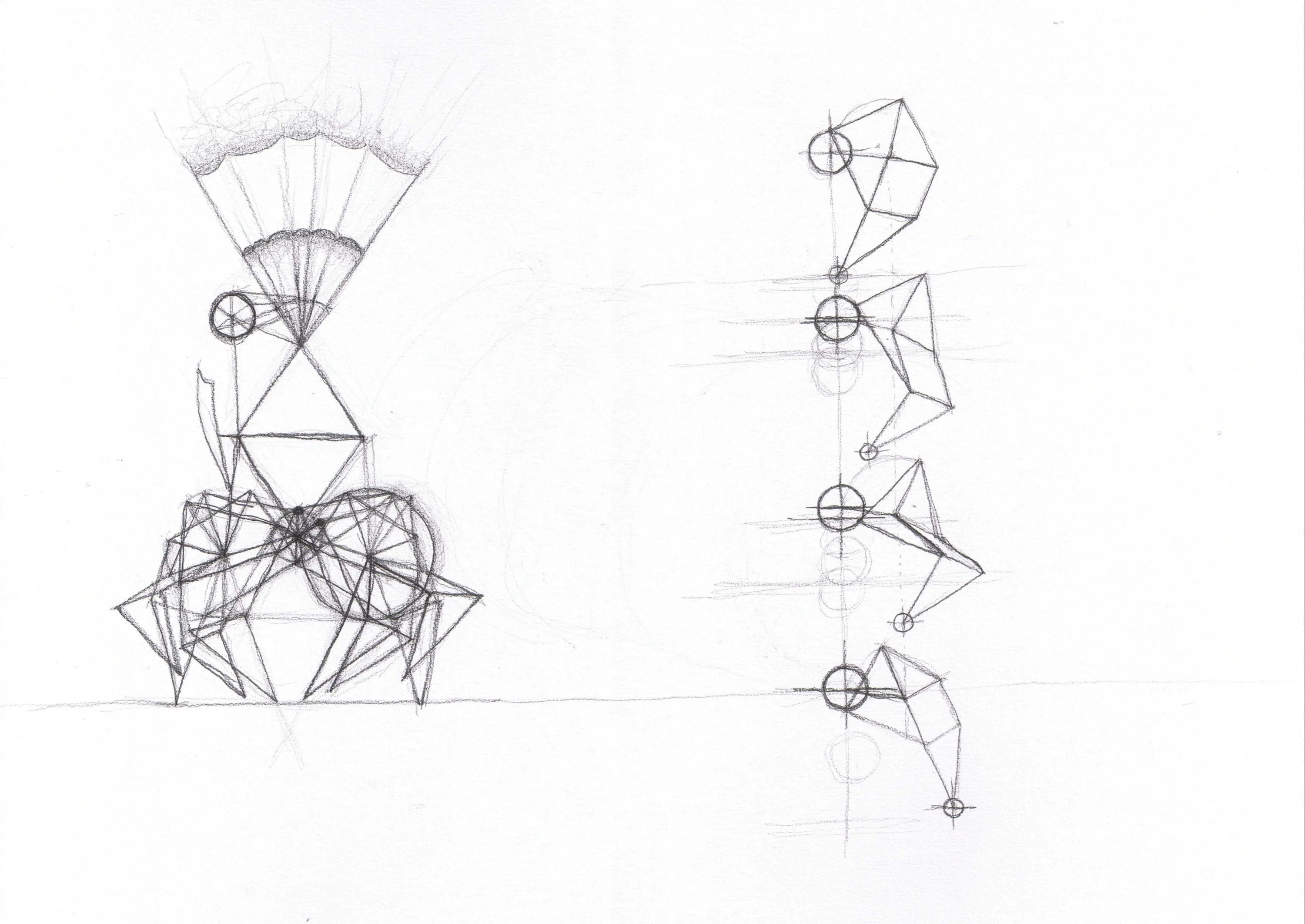

In the 1980s, Theo Jansen wrote a regular column for a Dutch newspaper. “Usually, these stories were excursions in imagination,” he says. One of them involved an idea to help protect The Netherlands’ coastline from rising sea levels. Theo imagined wind-powered skeletons placed on a beach. Driven around by the wind they would gather sand to create dunes which would act as dams. “That was just a sort of fantasy,” he admits.

It remained a fantasy until six months later, when he passed a tool shop and saw PVC tubes used to cover electrical wires. He played with them for a day and saw so many possibilities that he promised to spend a year working with them. “That was in 1990, and then it got totally out of hand.”

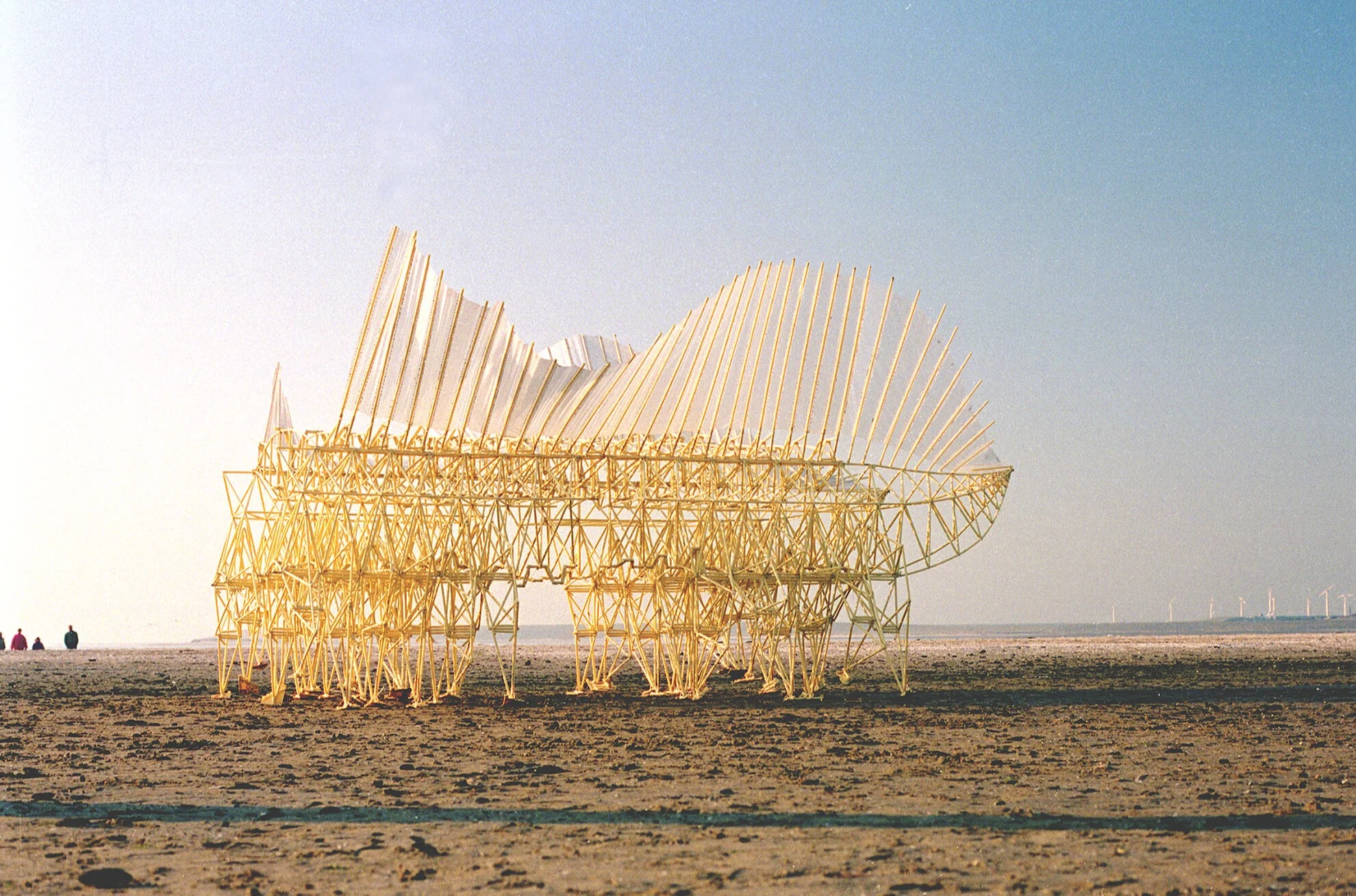

Theo’s Strandbeasts were born. Stunning PVC lifeforms that move of their own accord, they’ve been seen by millions of people across the internet and exhibited around the world.

Born in The Hague near the beaches he wrote about, Theo comes from a scientific background, having studied applied physics at Delft University of Technology. But he admits he was never too dedicated to his course; he was already dipping his toes in the art world, and one day he decided he liked painting more than studying.

I had to adjust my imagination and wonder how to make things stronger.

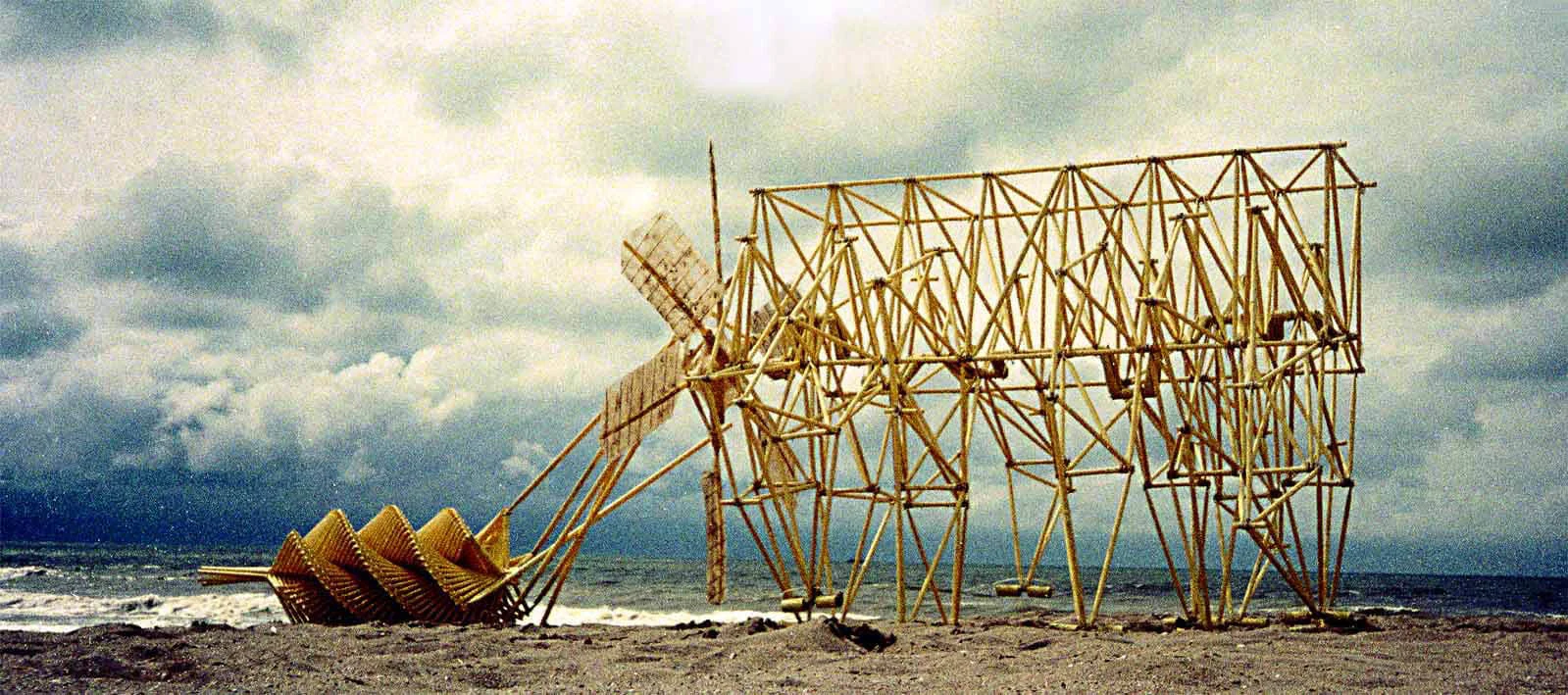

Despite his interests moving away from science, his background helped him as he began work on the beasts. The first one took him a year to build, and it couldn’t stand up, or move its legs while laying on its back. “I’m not surprised now. Looking back it was a bit optimistic,” he says. “It just looks so clumsy. The joints were made of sellotape.” Despite this disappointment, Theo learned a lot that year. What fascinated him most was the idea that his creations could be improved.

He had just read Richard Dawkins’ The Blind Watchmaker , which tries to counter the main arguments against Darwin’s theory of evolution. “I was just so inspired by that book. It gave me so much information about our origin,” Theo says. “I had sleepless nights thinking about all the animals in the world and how they came about.”

With the theory of evolution firmly in his mind, Theo learned to take early disappointments in his stride. “Every time something went wrong, I would see the beast as a mutant, and most mutants fail,” he says. “There always comes a moment when something will happen, usually unexpectedly. You’ll make a mistake and you’ll learn something very useful. And then you can climb up the ladder.”

The early beasts were stiff enough to stand up to the wind, but their weak joints were a problem. Theo would often overestimate the strength of these joints, and sometimes their backbones would even break. “I had to adjust my imagination and wonder how to make things stronger,” he says.

You can see the parallels between real-world evolution and Theo’s practice. “Once a tube breaks, you replace it with a thicker tube, and there comes a moment when they don’t break anymore,” he says.

Although he is technically their creator, Theo has a complicated relationship with the beasts. “I’m not a god who has a very intelligent design in my head,” he says. “Normally my ideas don’t work, and these tubes always seem to want something else. I have to find out what they want.

“The path I walk is very capricious and unpredictable, and in the end, when it’s finished, it turns out the tubes have better ideas than I do.” He is the maker, but he doesn’t feel in control. “It’s a dialogue. The tubes start talking to you after a while if you listen.”

This listening process has now been going on for three decades, and the beasts have come a long way. Theo works on them throughout the autumn and winter, while the summer is reserved for testing on the beach. “At the end of the summer I declare the animals extinct. They all go to the boneyard, and I become a little bit wiser about how the next ones can best survive,” he says.

When he does test them in the summer months, he always draws a crowd. Often, people have no idea what he’s doing, but he feels like they somehow understand. They’re popular around the world too, especially in Japan and the US.

People respond in different ways. Some feel romance as they float across the beach on YouTube; others are obsessed with the technical details and the way they work. Some just find them funny. “Yes I’m quite democratic,” Theo says. “I try to give everybody something.”

I always like to show how they work myself, because they’re my children, you could say.

Having been fixated on this project for such a long time, has Theo’s feeling towards his beasts changed? “I think the love is the same. Still I am expecting a lot and I’m seeing a lot coming back in return, just as I did in the beginning,” he says. “In 1990 I was an irrational optimist,” he says. “It’s a lot easier to be positive now.”

And even though he has assistants who take on some of the technical work, if someone drops by his studio it’s always Theo who shows them how the beasts work. “I always like to do it myself, because they’re my children, you could say. I’m still very intrigued by both the existing beasts and the future beasts.”

Theo is not sure if his creations will ever fulfil the original purpose he mapped out in his column all those years ago. “I became so intrigued with the evolutionary process that I forgot to save the country,” he laughs. “Studying the principles of life and evolution is so much bigger than just saving the country. I’m over 70 now, so it’s about time I get a bit wiser.

“In the end, I would like to put all of this knowledge into one group of animals that can survive on their own, so they don’t need me anymore. Then I can quietly leave this planet, and there will be a new species on Earth.”