Hear the word tavern and you’ll probably imagine bars or pubs or inns where alcohol is sold and bought and the (mostly) good times roll. Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo’s experience of growing up in one was very different. For him, it was an unsettling place to be. He’s always struggled to process the things he saw as a child, but his photography project Slaghuis is a step on the road to doing so. He tells Alex Kahl about his story, and how he captured it so vividly in this series of burned, beaten, eerie photographs.

When South African photographer Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo’s parents were made redundant, they decided to open a family business in their home: a tavern. It was the first of its kind in the township, Lawley, at the time, and it was soon frequented by all kinds of customers. The tavern would get uncontrollably violent, to the point where people lost their lives. “Waking up to a dead body in the yard marks the day I was overwhelmed by the desire to disappear,” he says.

In his artist’s statement, he describes some of the things that would happen in the tavern. Thembinkosi saw things that no person should see, let alone a child, and he’s felt the impact ever since. “I walked around the streets heavy with guilt and shame,” he says. “Home couldn’t be my safe haven like most children. It was an extension of the tavern. My mind began to have violent thoughts and wishes.”

The infamy of the family business meant it was given the name Slaguis, literally translating to slaughterhouse or butchery. “I would find it hard to breathe whenever that term was thrown around in conversation as people recounted the latest violent happenings of the place,” Thembinkosi recalls. When Jabulani Dlamini, a mentor and friend of his, suggested that he title this project Slaghuis, he was petrified. “And because of that feeling I knew I had to call it that.”

Thembinkosi had always been fascinated by the idea of communicating your own world visually, and he saw photography as a way of understanding his thoughts about his childhood. He thought a series about his early years might allow him to have a conversation with himself that he previously hadn’t been able to have. Like many people, Thembinkosi found that there was only so much progress he could make by talking to people or to himself about his experience.

Writer Terry Sullivan once told the story of a mass shooting that happened on a train, when he was just two carriages away. He speaks of the often unmanageable trauma it caused. He had always used words to explore his thoughts, but after this event, he “felt as though words had lost their efficacy.”

He began to paint still-life works of train cars and commuters as a way to ease his mind, and he spoke to Dr. Robert Ursano, professor of psychiatry and neuroscience and a founding director of the Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress, about why this might be helping him. Dr Ursano explained that “we know recounting the story can be a valuable part of recovery” and that “those elements – the recalling and setting to rest, and putting it in a meaningful context – are part of the recovery process.”

Home couldn’t be my safe haven like most children.

As he explains, the value doesn’t solely come from recalling the events and from considering their weight, but also from taking these negative memories and using them to create something that can mean more to you. Art can allow you to recall old memories and assign emotions to them, and can also be used as a way to give these memories a beginning, middle and end in the pursuit of closure or moving forward.

It’s a process that often requires a confrontation of some kind, or a meeting with memories that may not want to be met. Terry started to create his art just a year after his experience on the train, but Thembinkosi needed more time to prepare himself. “It was only in 2018 that I was finally ready to confront the tavern space, to have a conversation with it, to show how it impacted me, how it had made me a butcher in my mind,” he says.

He created the series in the space he grew up in, and this is often another important factor in overcoming trauma. “You can finally have a sense of control over that space,” Dr Ursano explained to Terry when he started to paint scenes from trains. In depicting his childhood home, Thembinkosi was chasing that same sense of control. “It was a space that marked me, and so I created the series from these markings,” Thembinkosi says. His series speaks to his own experience of the tavern, the silent moments when the customers were gone and when the space had to be used as a home again. It's a raw and uncomfortable series that perfectly captures his lasting sense of hopelessness.

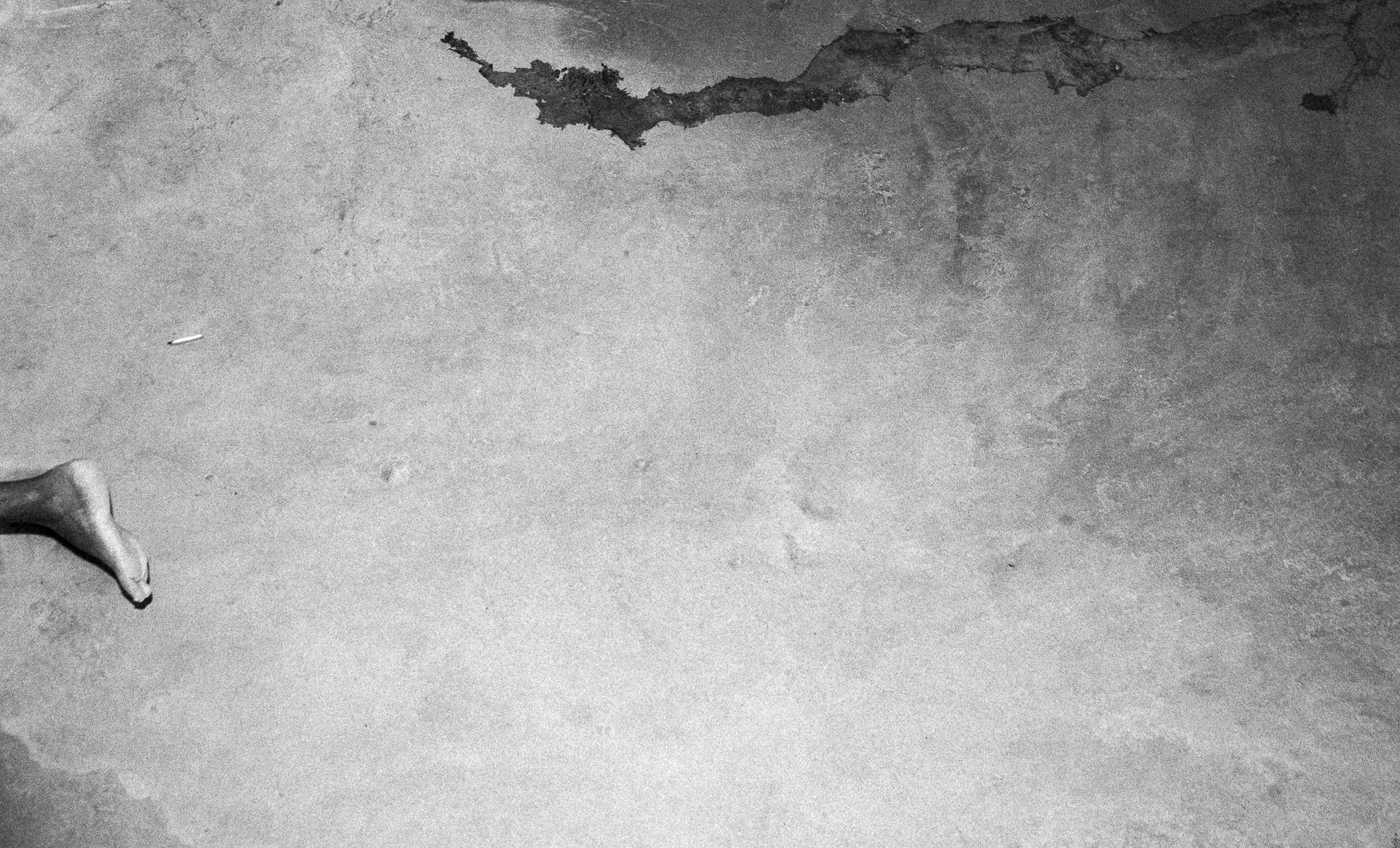

The images were informed by the sounds he remembered, the way the walls looked, the violence in the word “Slaghuis.” “All of this made me remember certain events that carried emotions that I needed to deal with,” he says. Squalid walls and floors are the most prominent feature of every shot, covered with stains and thinning paint. Some photos seem to depict some abandoned old hospital, showing makeshift beds covered with filthy cloth material. The photos could easily be lifted straight from a horror film, with stray limbs poking into the frame from random corners, spent matches strewn about the floor, and used rubber gloves slung over the top of one wall above a sink filled with putrid water.

It was a space that marked me, and so I created the series from these markings.

The images are made all the more eerie and anxiety-inducing when Thembinkosi marks them once they’ve been developed. There was an urge to get physical with the image,” he says. “I tend to do it in a violent way.” As a child, he would think about how the customers would leave their mark on the tavern when they left, and he wanted to mark the photos in the same way. He tore and burned the images as a way to put his own emotions into them. He placed a few of them back in the tavern space for the punters to use as beer mats or to ash their cigarettes on, letting the tavern damage the photos in the same way it damaged him. Once he’d done that, he’d re-photograph the prints.

He remembers that most of his earliest encounters with the violence in the tavern were seen through a window. “I’d look through the window to see if my parents were okay, but there was always something obstructing the view, like the curtains or the burglar bars,” he says. It’s because of this that he was inclined to prevent a full view of the scenes by tearing or burning certain sections.

Thembinkosi has always worried endlessly about the impact his upbringing and the things he saw will have on him, but also on his future children. He knows that these early memories mark the adults we become, and he’s scared that, if he doesn’t deal with these emotions, he’ll pass them on. “That’s why it’s been so important for me to tell and retell my story to myself, and the process of making this series has been so healing.”

“It’s interesting. If you retell your traumatic story enough, it can reach a point where it is almost no longer yours,” he says. “It becomes lighter. I think the process creates one anew, and makes you open for new experiences. It’s not about forgetting. It’s about recounting your trauma until you have this awareness that sets you free.”