As Thato Toeba says, just because a person is not present in the archives of their country, that doesn’t mean they weren’t present in the place’s history. The artist and researcher tells Makella Ama how their mixed-media collages combine pieces of images new and old to question the accuracy of historical archives, and to celebrate the ways the tenderness and the hardships of life intertwine.

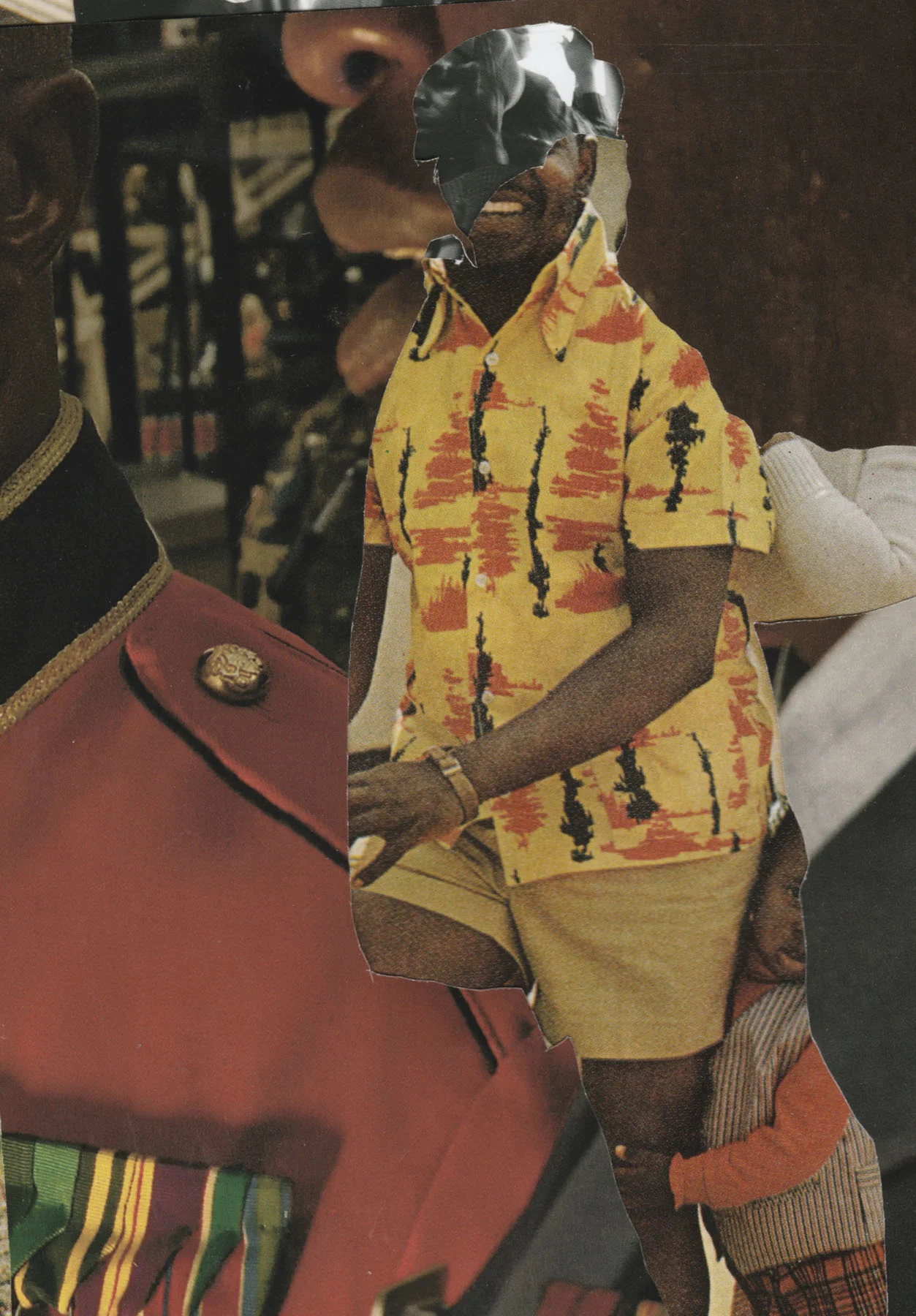

Thato Toeba is an artist and researcher from Lesotho, whose collages touch on personhood, politics, propaganda, nationality and globalization. Influenced by a “suspicion of things such as politics and institutions” which can intrude on the emancipated joy of life, they use photographs to convey “how much of what is socially obeyed is hallucinated.”

Born in 1990, Toeba, an artist, lawyer and (occasional) researcher, traces the beginning of these intentional thoughts to their time spent studying law at the National University of Lesotho. Attending lectures during the time of the FeesMustFall movement in South Africa, they began to consider what it means to exist in a world where juxtapositions exist in abundance. “The university was literally burning because people wanted a decolonial approach to education,” Toeba says, “and we were studying the colonial rhetoric about the world. I always found that contradiction interesting and it made it very difficult to do research within that convention.”

Toeba describes their work as emerging out of a counterintuitive impulse to their academic experience; it’s a raised eyebrow at the concept of “reliable sources,” something they think about often as someone studying criminal law in South Africa. Recently, they founded the Lesotho Archives, which they describe as “an open source for anyone interested in the history of Lesotho…a country that can be “very specific about who it glorifies and who it ridicules.” Here Toeba acknowledges inherent biases—some intentional, some unintentional—that exist within ethnographic records of people.

People like me with my background and sexuality are not in the archives, but we are there in history.

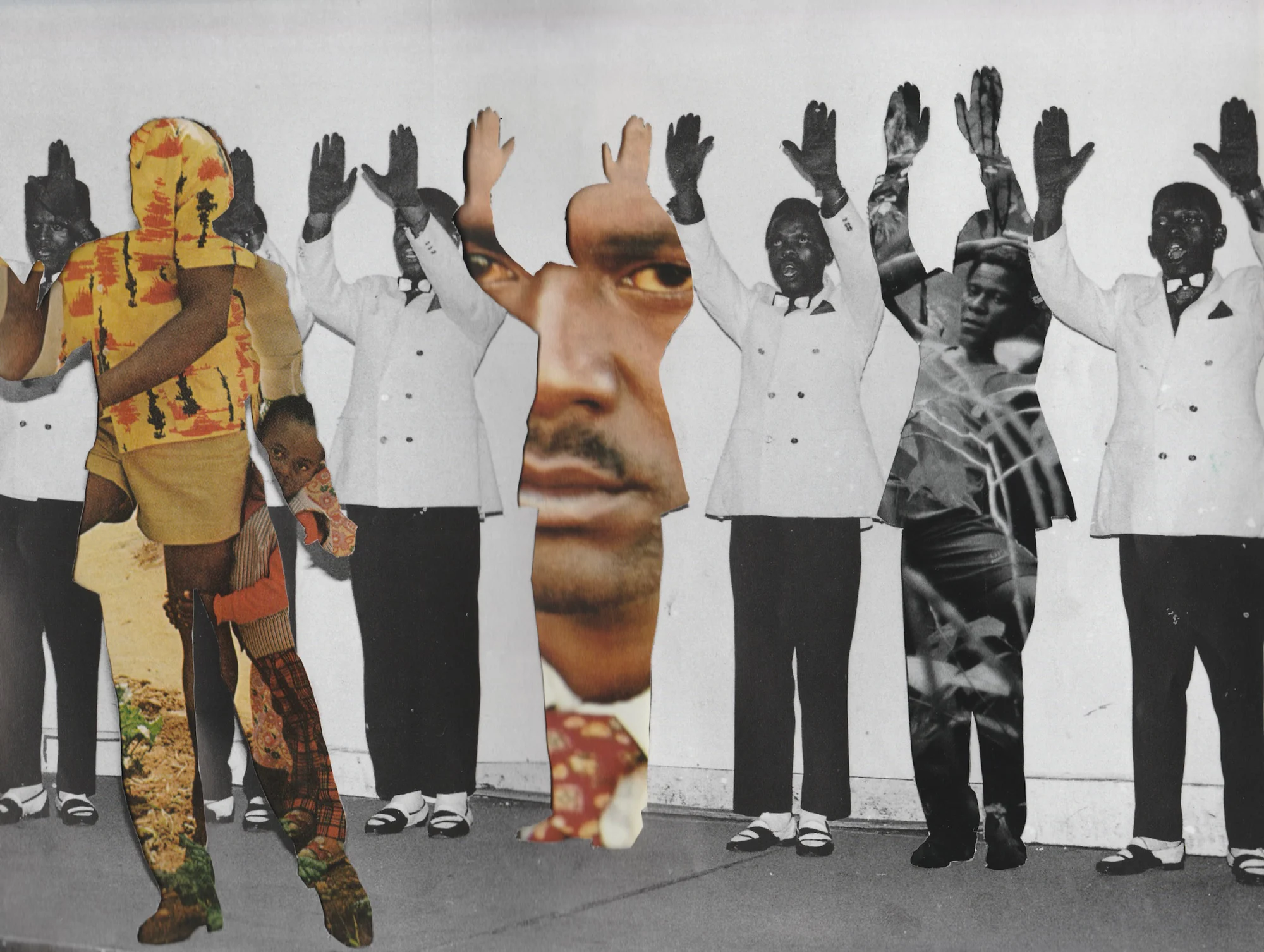

One of the impacts of this reframing is how Toeba now considers the sources of materials used while collaging, such as archival photographs. “When we think of questions like ‘should we leave the archives alone,’ it already isn’t alone,” Toeba says. “It’s a very metaphoric preposition about the presence and absence of people in the world. I am not in the archives in Lesotho. People like me with my background and sexuality are not in the archives. We’re not there, but we are there in history. The people that are excluded from the archive are nonetheless present in the history of the place.”

Throughout Toeba’s works, we see inclusion; of age, of life, of sexualities and of gender. Despite this, they consider the ethics of manipulation and world-building using other people’s stories. “I always have questions, like do they even want to be here? Do I have the right to liberate you? Is this liberating? There’s a lot of politicking that happens in my mind,” says Toeba. “But then there’s also the question of whether you can just let the archive be, without commentary? Without any type of intervention? I don’t know whether all archives are better left alone.”

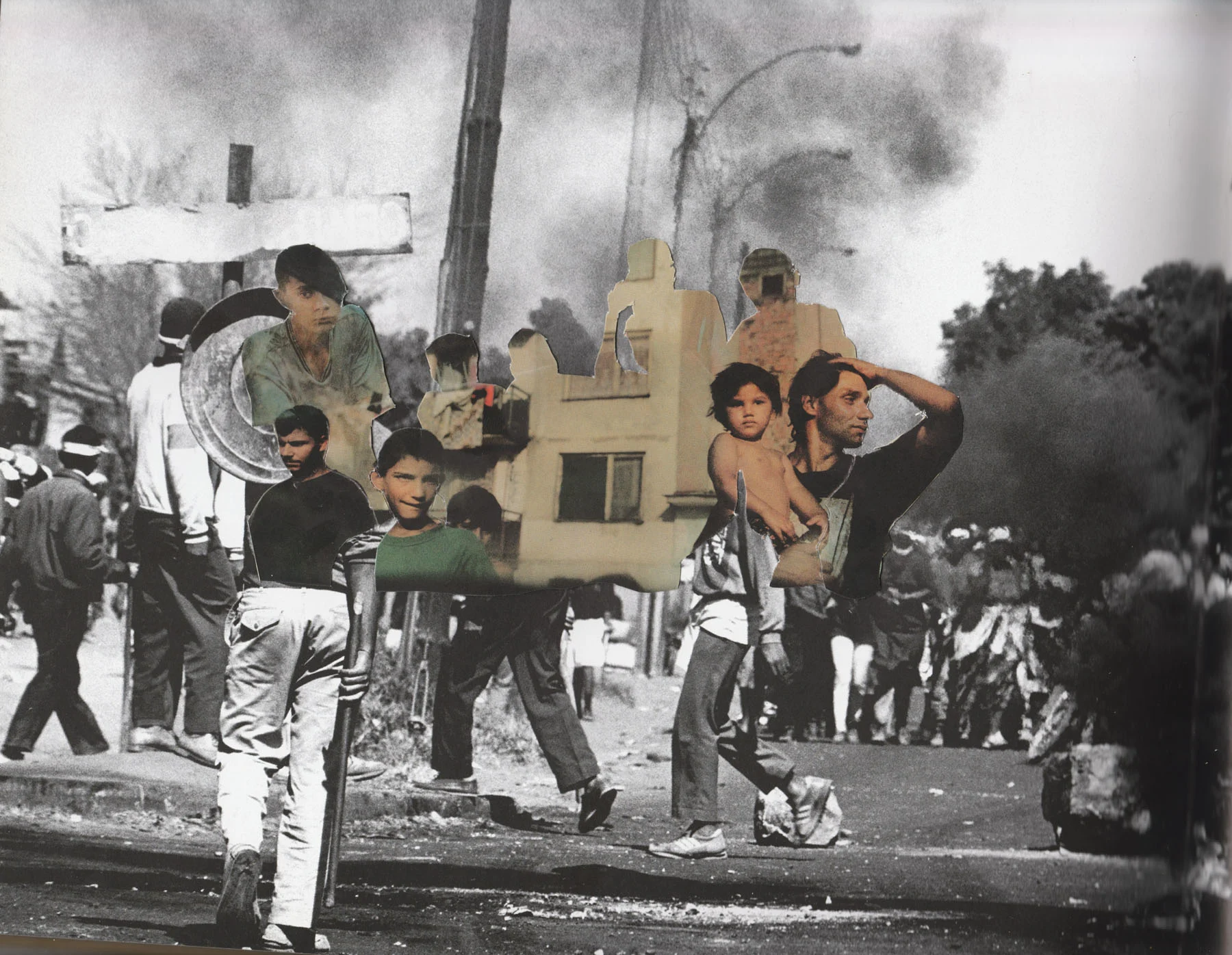

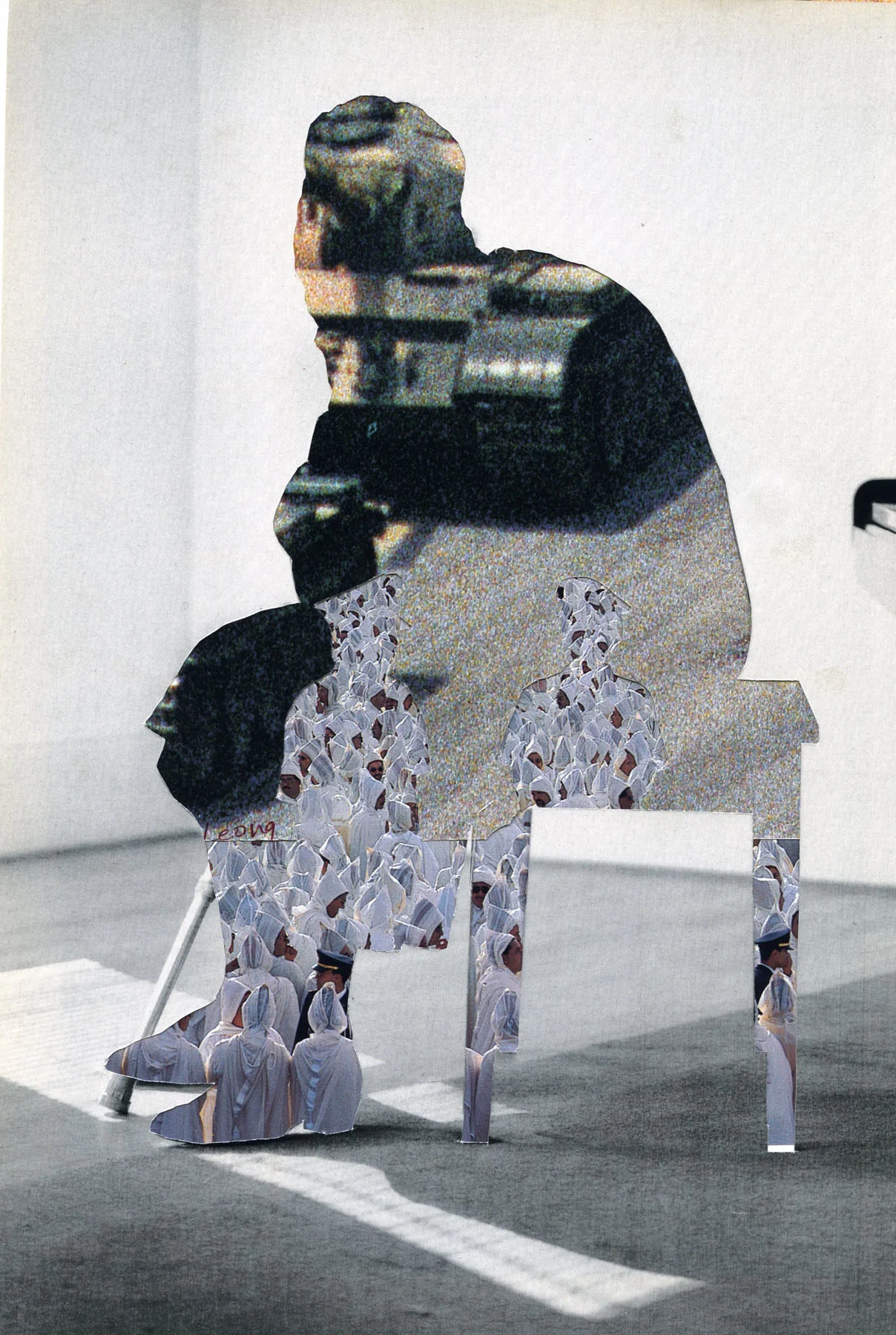

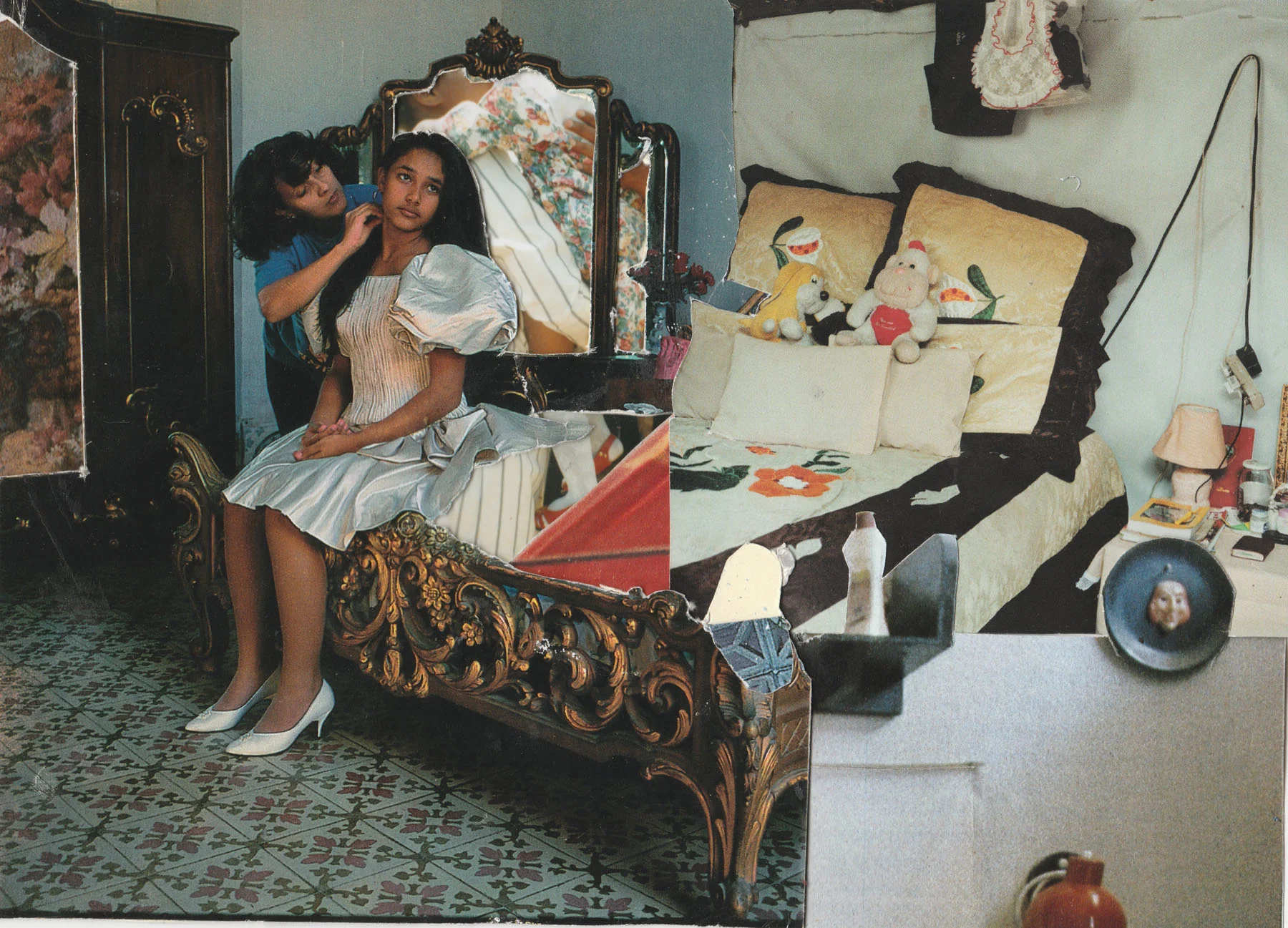

In works like “Ka ha ka ka mona ha se ka mantloaneng” (don’t play in my house), we see a textured, pieced-together bedroom filled with fragments of sentimentality. Stuffed teddy bears, a bronze bed, a flower-embroidered blanket. In the center of all this sits a daughter, head turned to the side as her mother does her hair. Meanwhile, in works like “I’m alive, and I will have to live” we see collages of fleeing men and silhouettes of army tanks.

“I understand that sometimes, we just want to see beautiful things,” Toeba says. “But the world is not always beautiful. At the same time, I know that life is not hideous, so I’m always trying to contrast brutal things like war with tender situations like someone doing your hair.”

Even in moments where it feels like the world is falling apart, someone is making food, someone is doing someone’s hair.

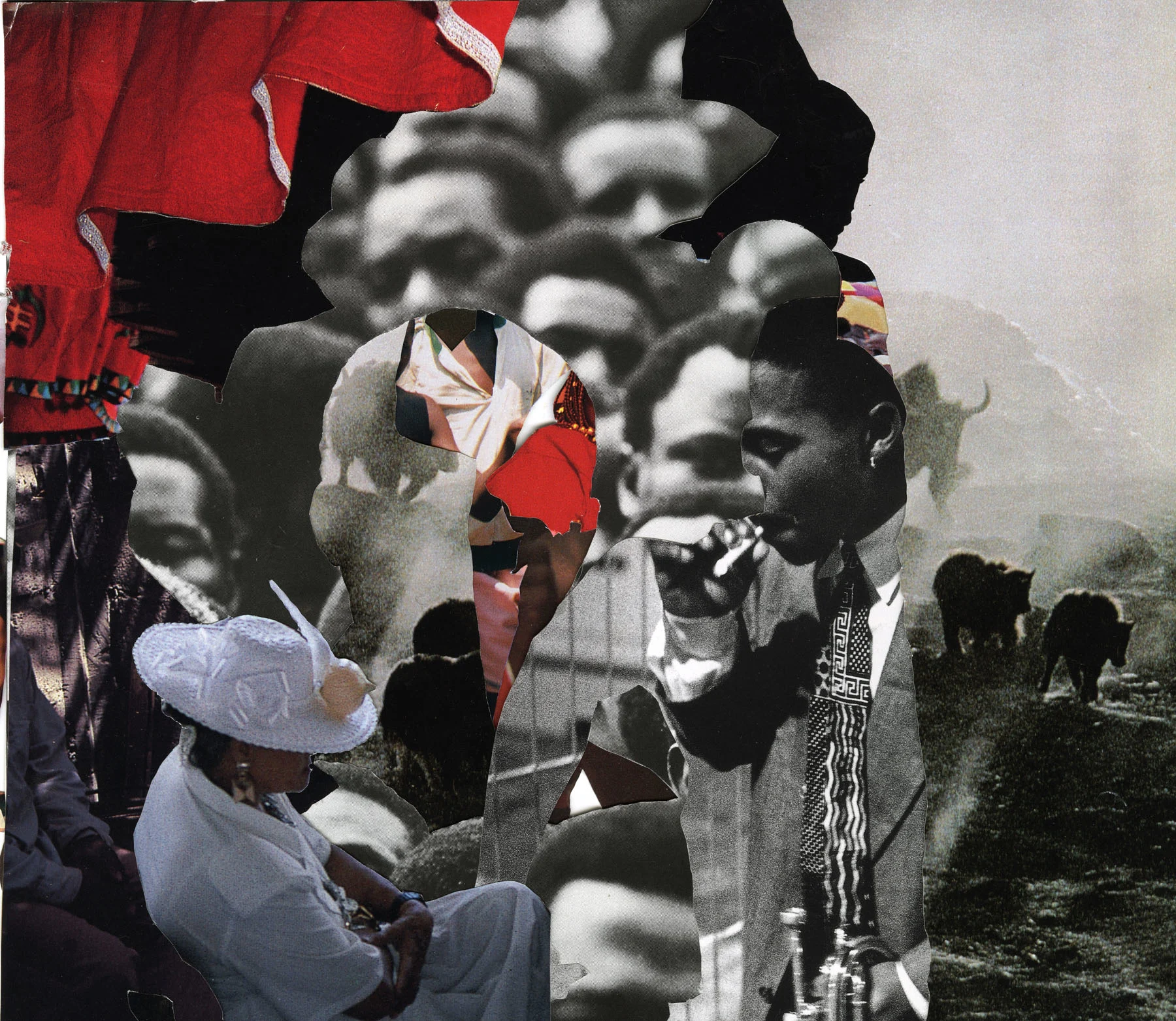

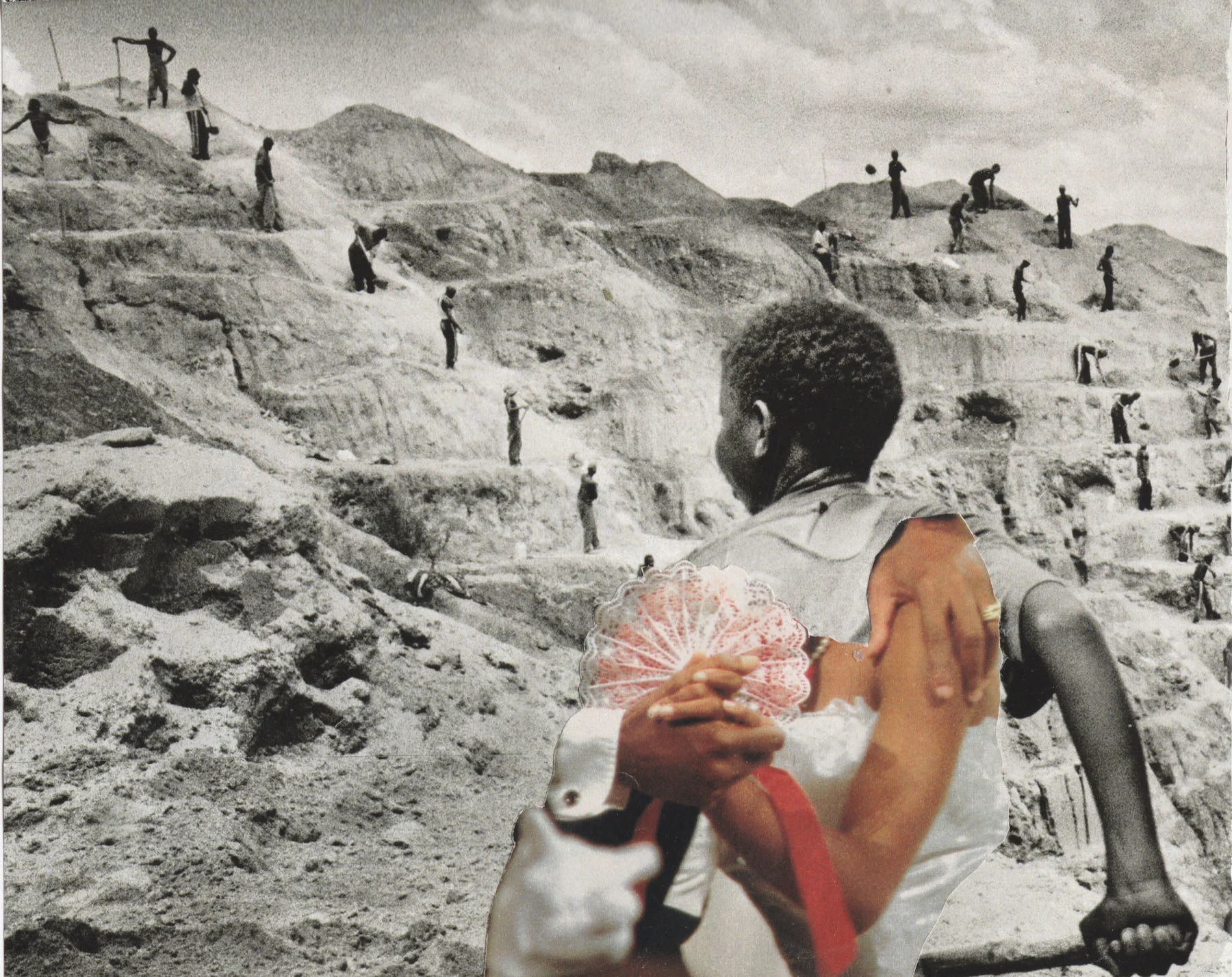

Seemingly contrasting themes come together again in “E-motionz.” We see elements of tenderness and compassion through the dismembered clasping of hands and arms placed into the silhouette of a boy. His body is turned towards what seems to be a sand mine occupied by laboring men. Here, we grapple with the idea of what it means to be held during moments of hardship. Although the hands may signify tenderness for one viewer, they could embody feelings of confinement for another.

Toeba explores difficult and painful themes without forgetting the often beautiful mundanities of everyday life. There’s a sensitivity in the way they merge these two disparate yet very connected things. “Even in moments where it feels like the world is falling apart, there are always things that are just ‘things’ happening,” Toeba says. “Someone is making food, someone is doing someone’s hair. In spite of bigger political moments, life continues to happen in its small ways.”