Music has long been a key medium for activism, with artists through the decades using their lyrics to share powerful messages of protest. In an age where these messages now play out on screen too - whether that’s at some of the world’s biggest festivals or simply the screen in your hand – those voices are connecting with audiences like never before. And for many artists, when they need these amplified they turn to Tawbox. David Renshaw meets the creative studio helping the likes of Stormzy and Dave bring politics to the stage.

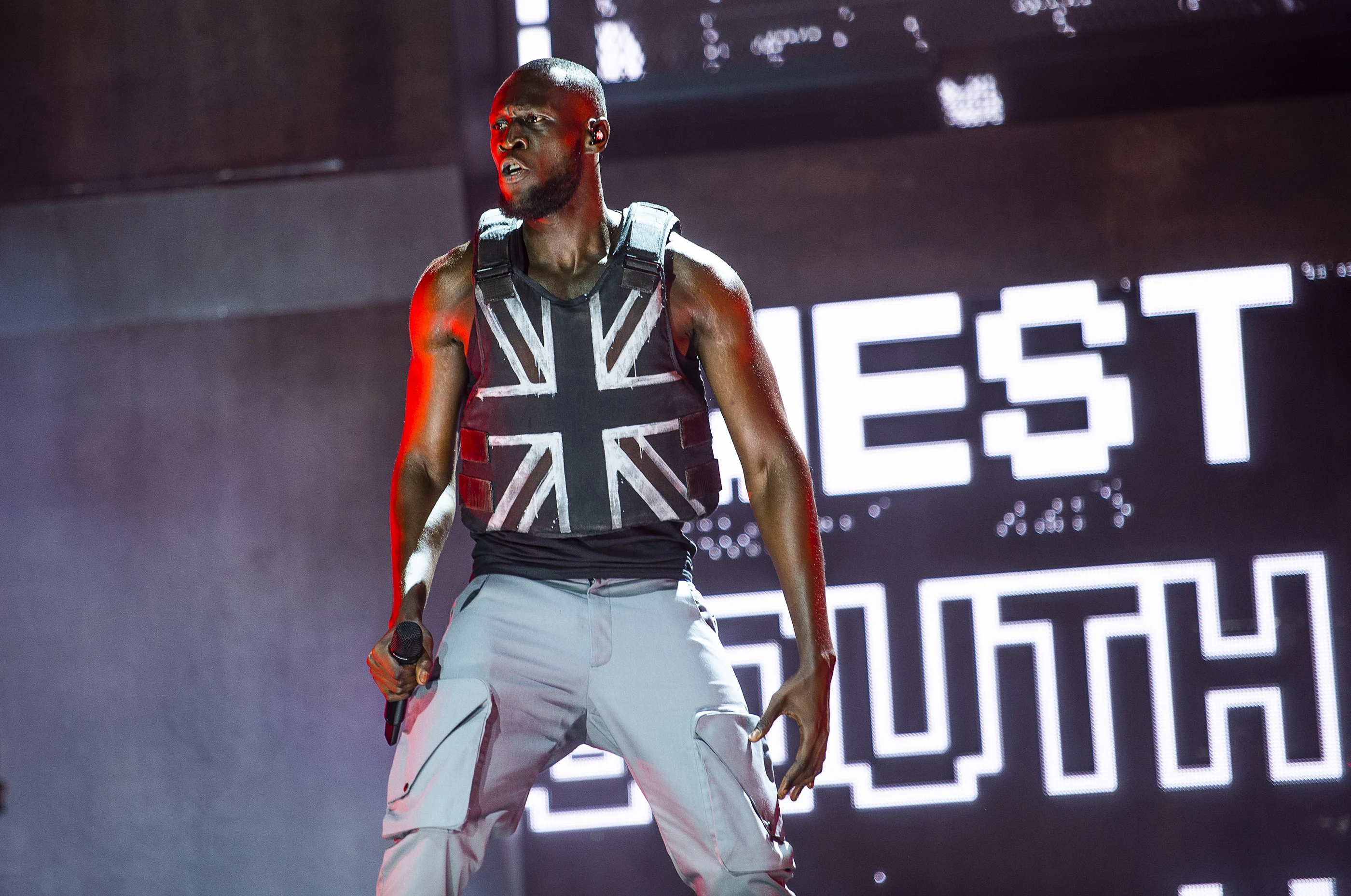

When Stormzy was announced as one of the 2019 Glastonbury headliners he knew it was a momentous occasion in his career. Not only was he the first grime MC to headline the festival, he also became just the second Black British artist in history to do so (Skunk Anansie, fronted by Skin, were the first in 1999). Naturally, he needed to reflect this and he knew just the people to call. Tawbox is the brainchild of Amber Rimmel and Chris “Bronski” Jablonski and together they have established a creative studio behind some of the most memorable, and politically-charged, moments in recent live music history.

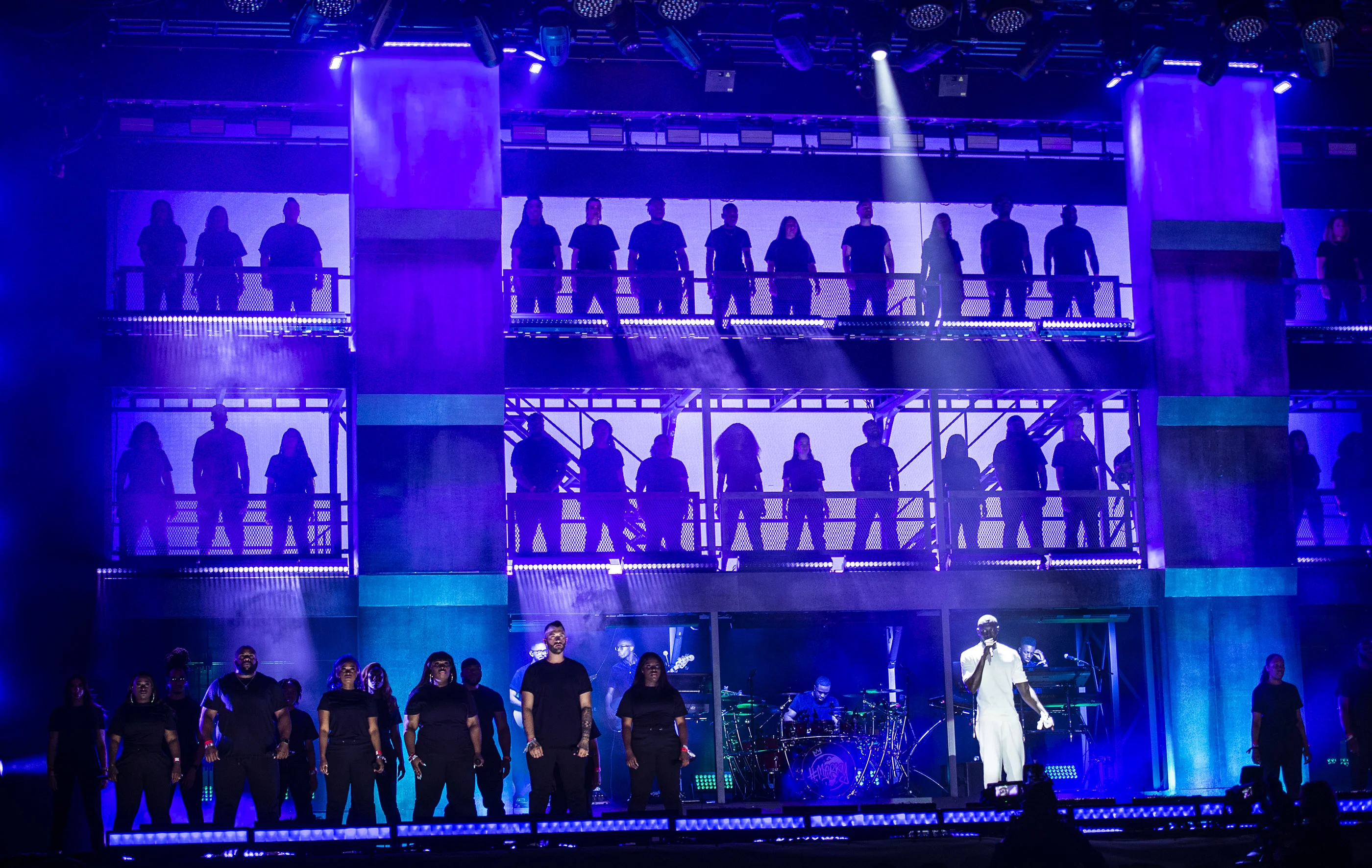

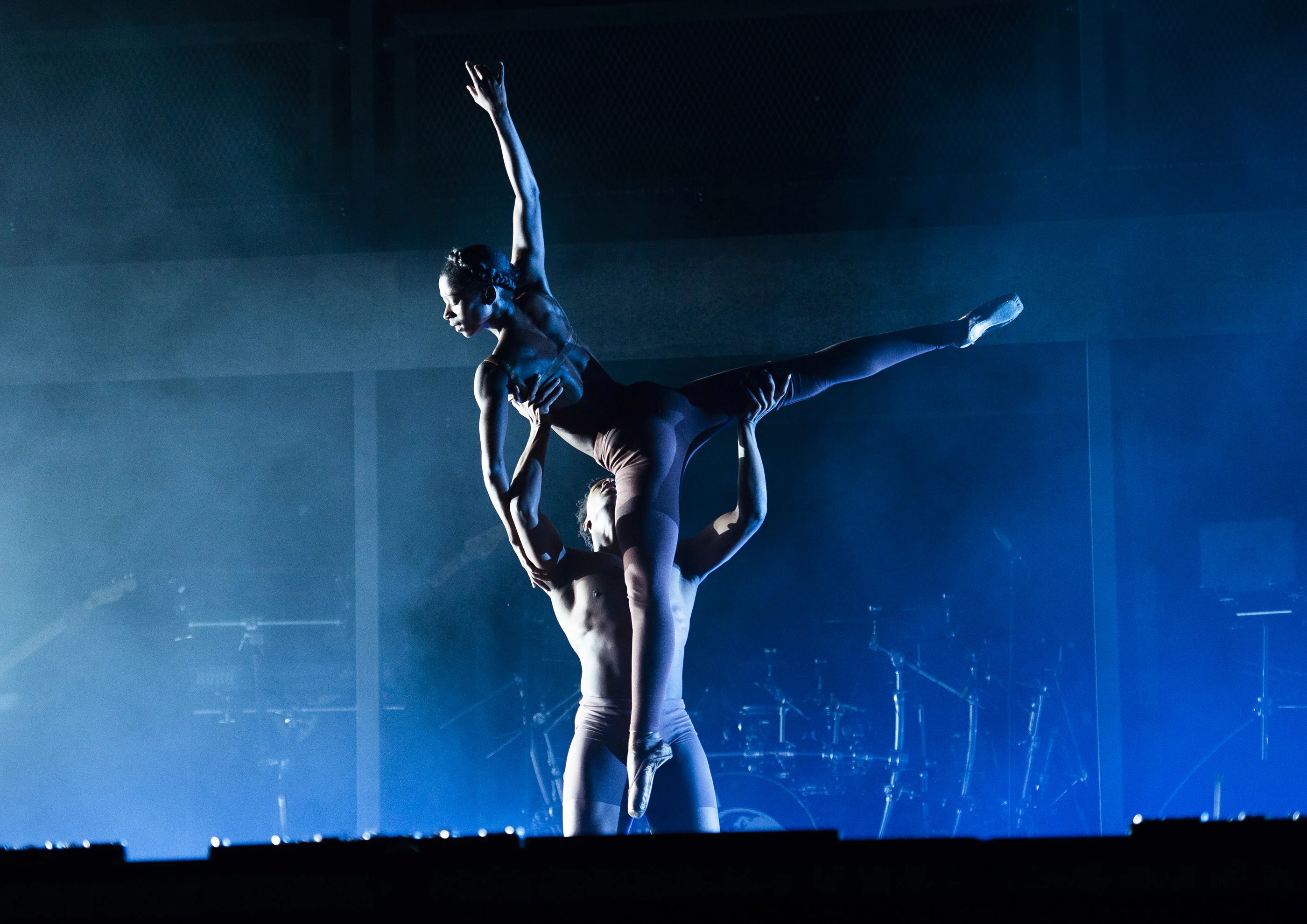

Tawbox had worked with Stormzy in the past on his 2017 UK tour, a run of shows that culminated in three nights at London’s O2 Academy Brixton. Glastonbury, with a capacity of 250,000, is significantly bigger though and the south London rapper knew that his position on the festival’s Pyramid Stage had to reflect something more than just his musical career. Throughout his set Stormzy highlighted the best in Black British culture, from shouting out his grime peers to highlighting the struggle of Black ballet dancers buying shoes in their natural skin tone. Early in the set Stormzy used audio of a speech given by David Lammy in which the MP for Tottenham spoke about the injustice of young Black people being criminalized in a biased and disproportionate justice system.

Bronski and Amber knew that there was a balancing act in filling the show with this content and not making a Friday night headline appearance into a lecture. “We could have taken the David Lammy speech and used it at the end of a song and that would really be saying, ‘I am making a statement,’” Bronski explains. “However, we put it at the beginning to set up a tone of the misrepresented Black british youth that we wanted to shine a light on.”

When you’re in the euphoria of a concert any messages that are given to you are very powerful.

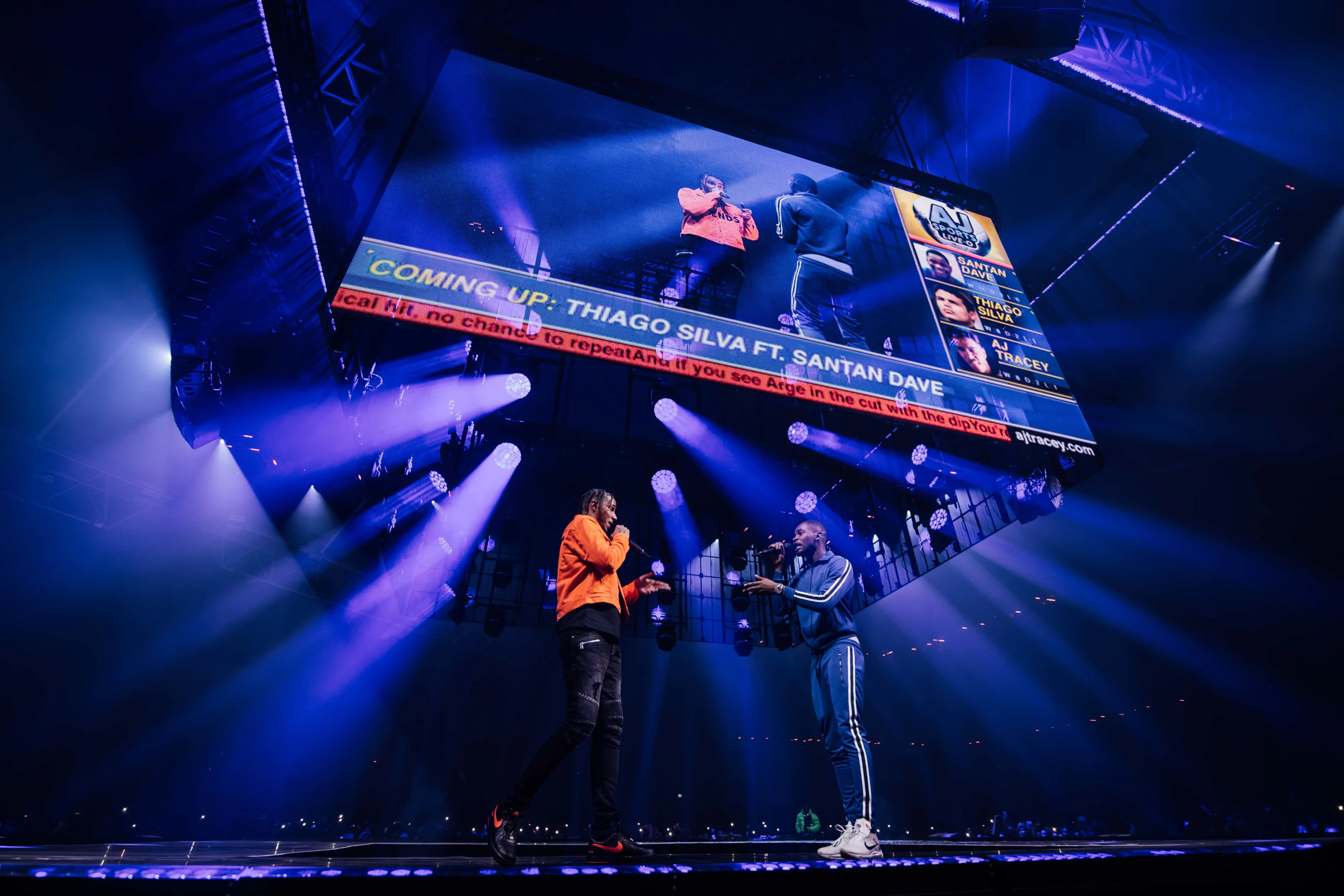

Throughout their career Tawbox have worked with both artists that like to make a political statement and those who don’t, but in recent years it's their work with the former that has grabbed attention. Having first met while working separately with UK trio N-Dubz, the real life couple first joined forces as creative directors on a 2018 Rita Ora tour. Since then they have built up a client list including AJ Tracey, Mabel, and Weezer. Amber began her career as a dancer and choreographer while Bronski has a history with the production side of live shows.

“I was the punk kid at school who had a ticket for everything,” Bronski says of his early gigging adventures. He fondly remembers seeing Marilyn Manson perform in front of a backdrop with the word “DRUGS” in 10 foot lettering. “That blew my mind. I’ll never forget that.” Those unforgettable experiences are what Tawbox aims to bring to the stage no matter who they work with. “We always think of the experience and the deeper meaning,” Amber explains. “How can we take the audience on a journey for the 90 minutes their favorite artist is on stage?”

Like Stormzy, many artists are increasingly using the stage to make overt political statements. Live performance has long been a platform for sharing your message but, as technology evolves and social media elevates people’s reach, the physical elements of live music are being utilized to amplify messaging and make it more viral and, arguably, more vital. Whether it is Kendrick Lamar walking out as part of a chain gang to perform The Blacker The Berry at the 2016 Grammys or Beyoncé paying tribute to America's historically Black colleges and universities at Coachella two years later, the biggest artists know that if they have something to say then the stage is the place to say it.

Notably, televised events are where these statement performances occur most often. Jennifer Lopez and Shakira’s 2020 Super Bowl half-time show, viewing figures for which reached hundreds of millions, featured images of immigrant families from Puerto Rico and children in cages. Meanwhile, to a smaller audience in Britain, rapper Slowthai made his feelings about Boris Johnson clear when he took to the stage at the 2019 Mercury Prize ceremony carrying a fake decapitated head of the Prime Minister.

The way Dave and Stormzy express themselves will inspire the next generation, too.

Jazz saxophonist Shabaka Hutchings’s work with Sons of Kemet is notable for its heartfelt politics. Their 2018 album Your Queen Is A Reptile is a post-Brexit confrontation of British nationalism and the monarchy. During a 2019 performance at London’s Somerset House the band projected racist language used by Boris Johnson, in which he referred to Black people in Africa as “flag-waving piccaninnies,” alongside the simple message of “RISE UP.” Speaking now, Shabaka says the words were put there as he understands that “music is something that disarms you. When you’re in the euphoria of a concert any messages that are given to you are very powerful.” He wanted to contrast the image of masses of African people in colonial times with those that had gathered to see him perform and consider themselves related.

Sons of Kemet, who operate on far stricter finances than a Glastonbury headliner, took the Somerset House performance as a rare chance to utilize a performance budget. While he acknowledges that not everyone can take those “financial risks,” Shabaka argues that it is worth it in the long-run. “I want that feeling of spinning the audience around and shoving them into another place,” he says. “It’s about connecting with individual hearts and minds. There might be one person there who has never thought about post-coloniality. As long as it reaches that one person, then the job is done.”

Putting your beliefs into your music and stage show is inherently divisive. Shabaka says that artists must be “mentally stable and aware of the need for self-care” when putting their politics on their sleeve. One layer of Stormzy’s Glastonbury appearance touched on this same fact. He took to the stage in a vest, designed by Banksy, daubed with a Union Jack. Bronski jokingly reveals that the priceless item “arrived in a Lidl bag” while Amber goes on to suggest its meaning was misinterpreted by some. “People described that as bullet-proof or stab-proof but I saw it as him protecting himself from political damage,” she says, highlighting the insidious presumptions that can slip into even the most well-meaning critics mind.

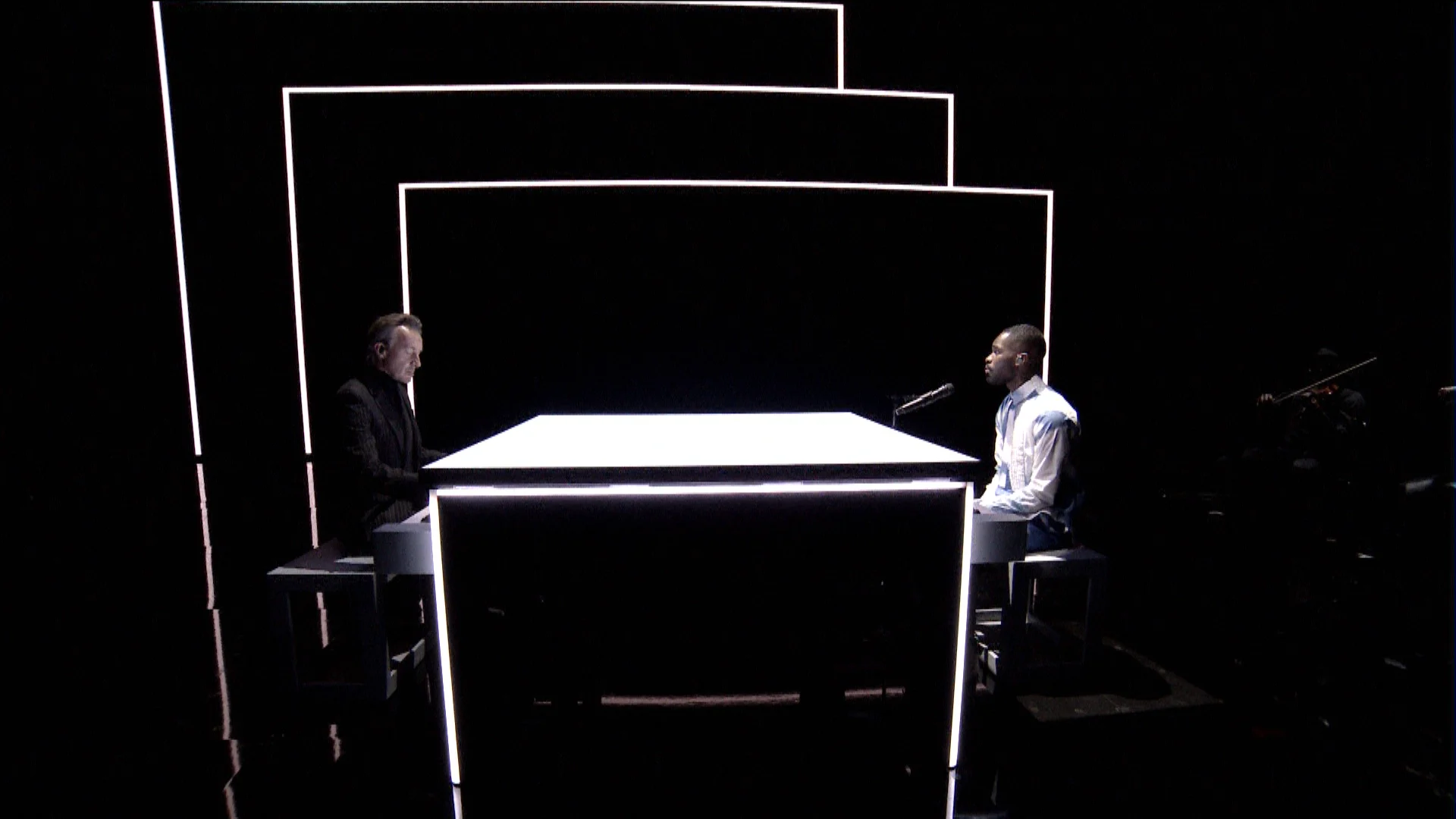

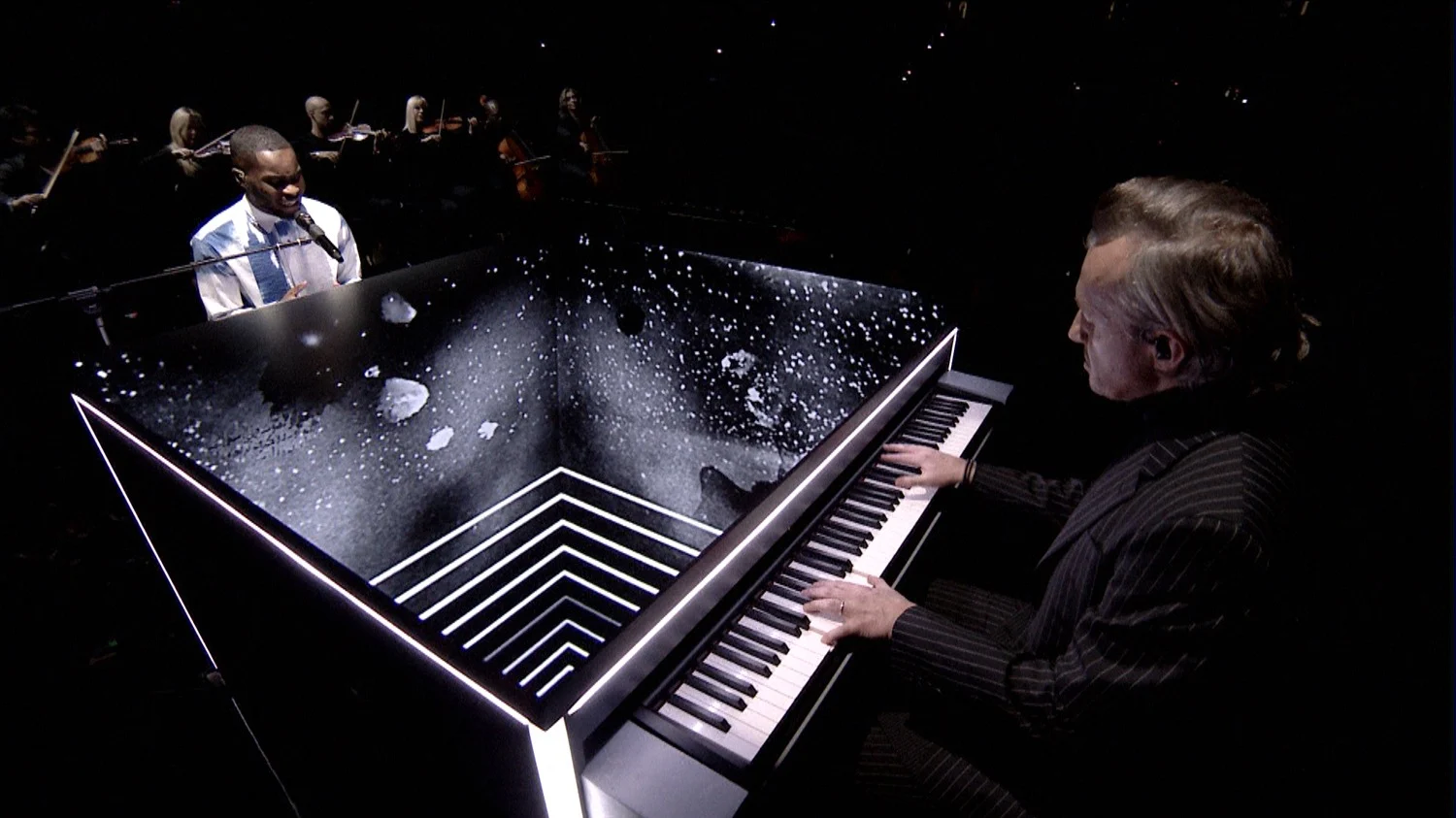

Amber and Bronski both agree that the audience at home is often as important as the one directly in front of the act on stage. “The first thing we always ask is ‘what is the canvas and where is it situated?’” Bronski says. “With Glastonbury that’s the Pyramid stage but it’s also the TV audience at home. It wasn’t just about the people in the field for us.” This approach became more explicit when they worked with UK rapper Dave on his performance of Black at the 2020 Brit Awards. Dave performed the song, a wounded but hopeful track about Black pain and brilliance, sat across from producer Fraser T. Smith while 3D images of prison bars, slavery, and the graffitied phrase “Go Home” were projected onto a piano they were both playing. “We had to send the pitch with a proof of concept,” Bronski recalls. “Imagine this double-ended piano with the deeper meaning that two races can share the same table.”

Dave added a new verse on the night for the millions of viewers watching at home on prime time TV in which he labelled Boris Johnson “a real racist” and called for justice for the victims of Grenfell Tower and the Windrush generation. It was a spine-tingling moment and one that highlighted how artists can clearly project a message on stage in an era when politicians on either side of the party divide struggle to make themselves heard. “With a track like that you get the chance to make the audience ask themselves questions,” Bronski says. “That’s when you get to that goosebump moment. Your brain is being challenged as you process what he has to say.” Both are in agreement, however, that taking overtly political statements does not work for every artist.

They know it worked for Dave and Stormzy because they directly reference the same things in their music as well as in interviews and on social media. “Glastonbury mirrored Stormzy’s growth as a person in airing his views on Twitter,” Amber suggests while suggesting these moments will pave the way for the future. “The way Dave and Stormzy express themselves will inspire the next generation, too. That’s really important.”

While Tawbox do not make exclusively political work on stage (shortly before Dave’s Brits performance they worked with Pussycat Dolls on a tabloid-titillating X-Factor performance), they believe that live shows are evolving into something more immersive than a simple performance. By drawing from the artists they work with they’re able to tailor that experience accordingly. It makes sense, then, that artists born into a more politically active and minded generation want to seize the platform and make their voices heard in a new way. There is a sense, whether talking to artists or the creatives behind the scenes, that the future of stage shows is not to blankly share a message but to punch through and loudly echo what is already in the air.