If you’ve ever stayed to watch the credits at the end of a movie, you’ll know how extensive the list of its makers can be. Expensive, time-consuming and risky for investors, filmmaking is one of the most difficult mountains to climb as a creative, especially when you’re just starting out. Here James Cartwright meets people who did it, to find out how.

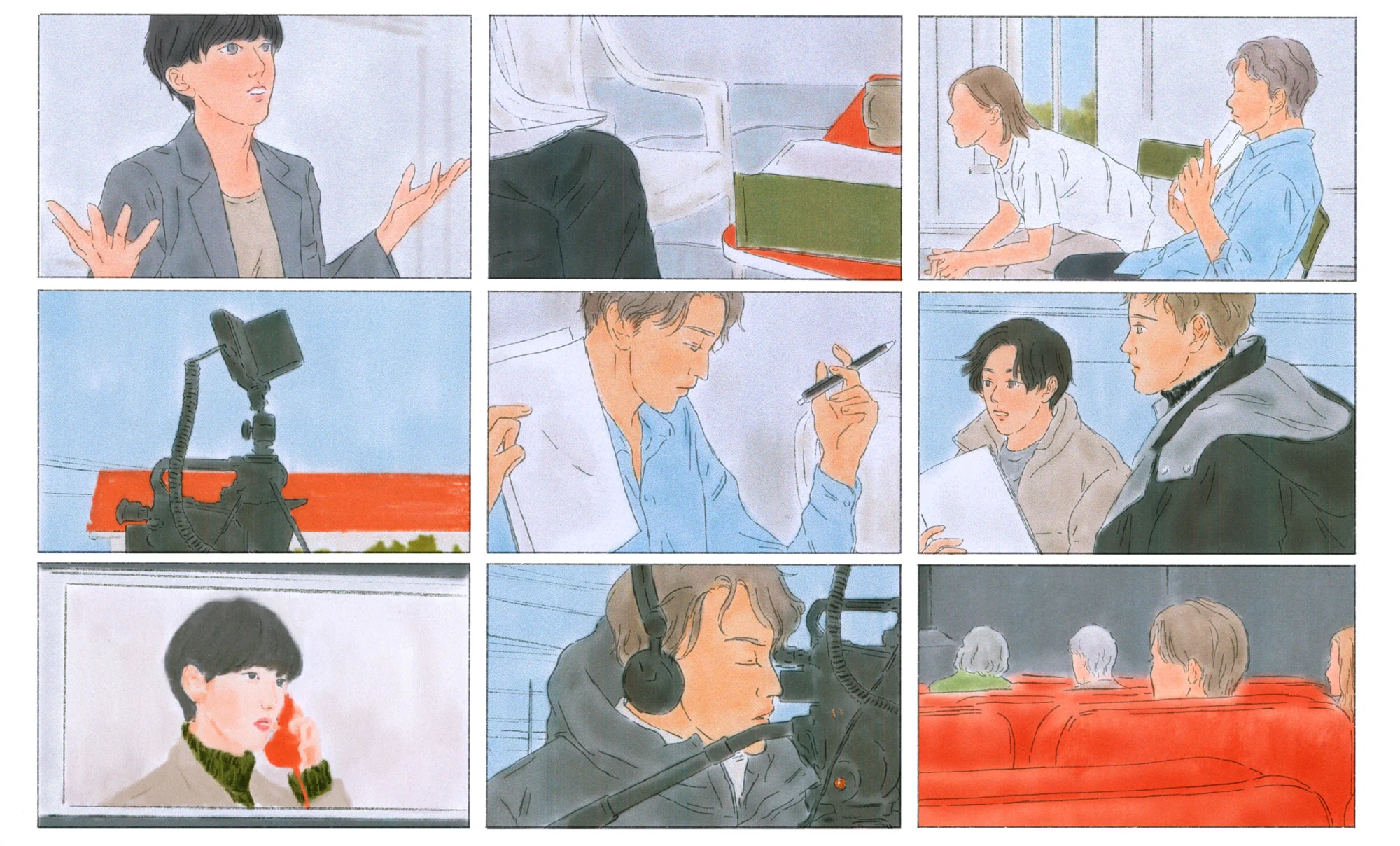

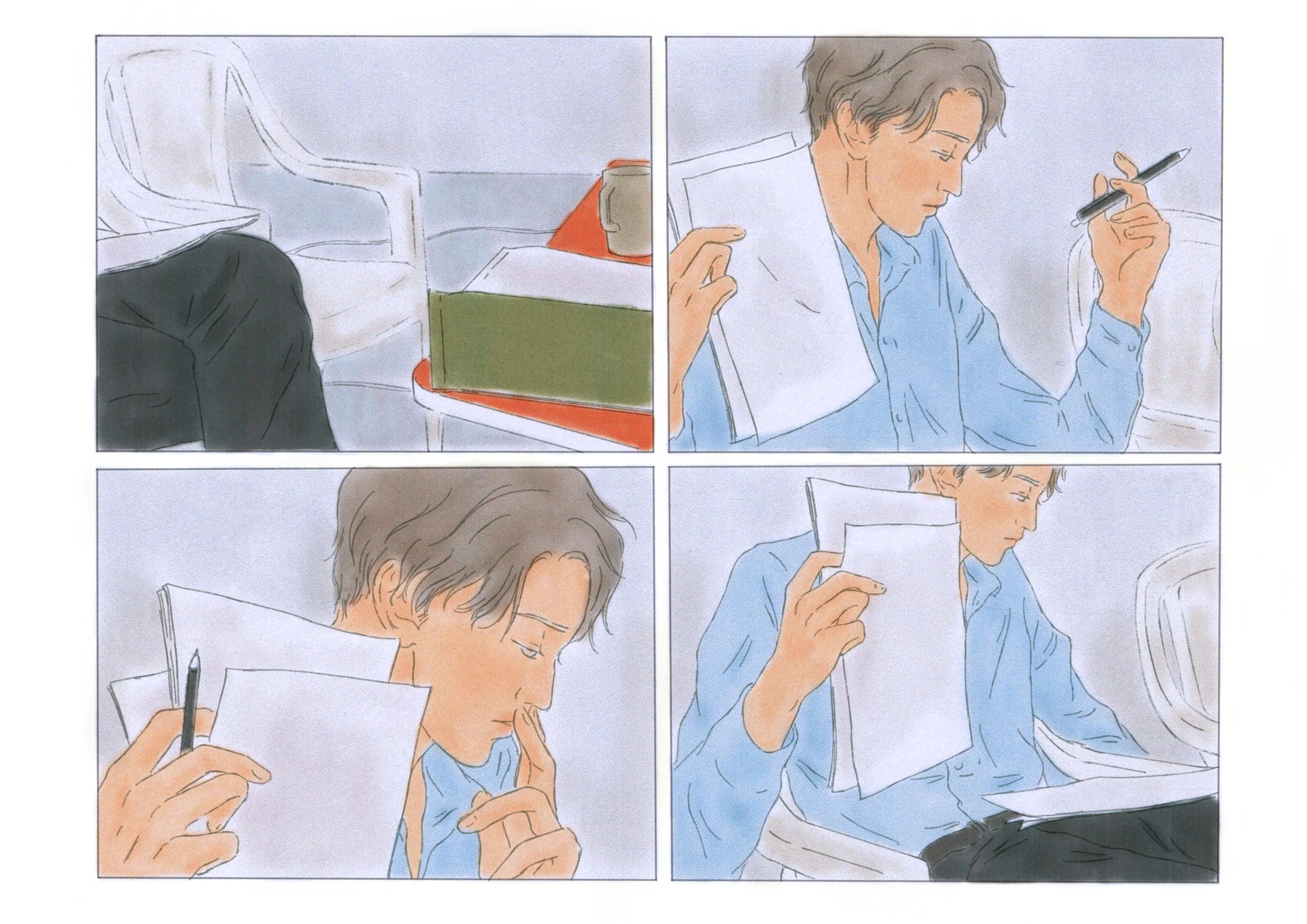

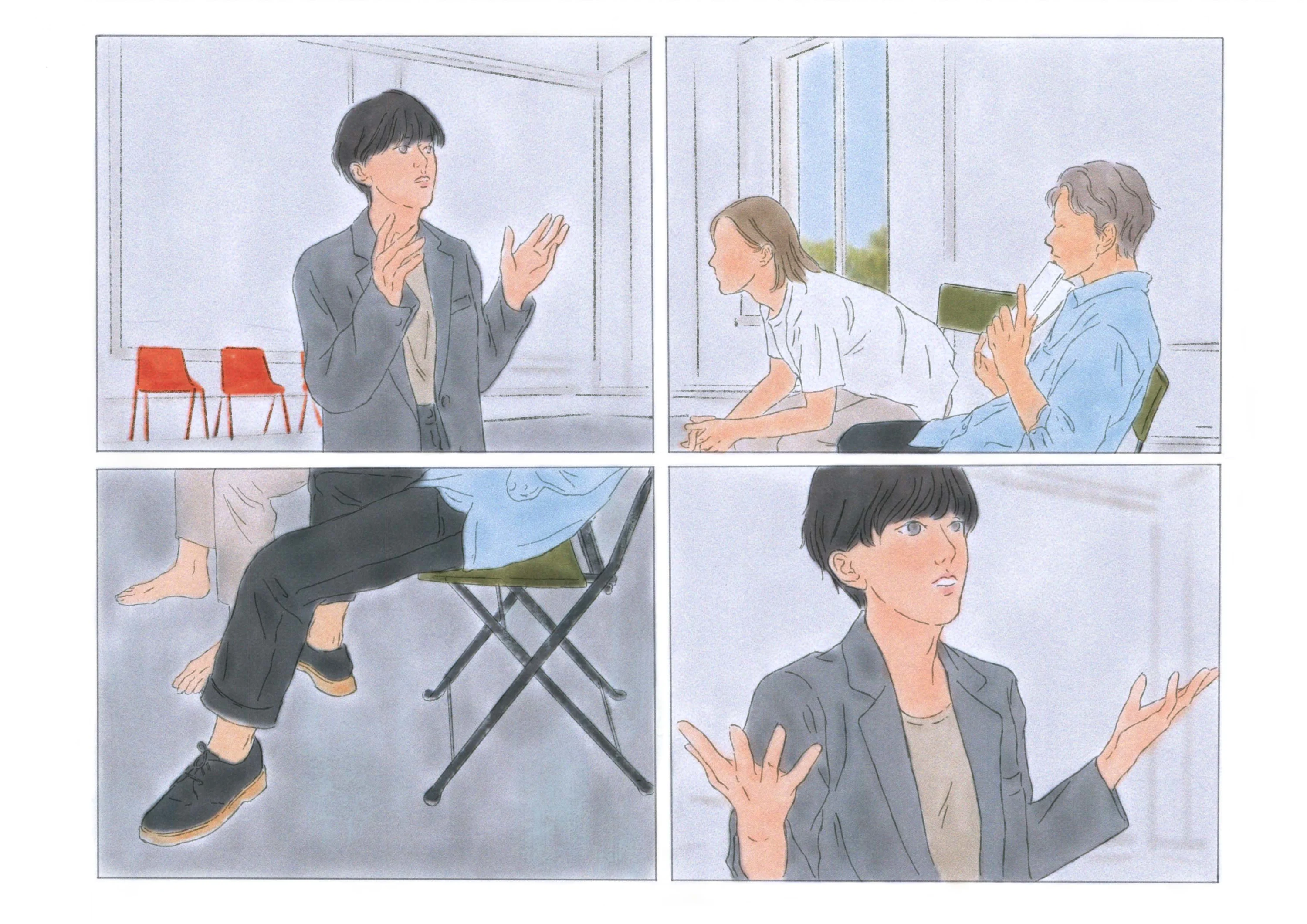

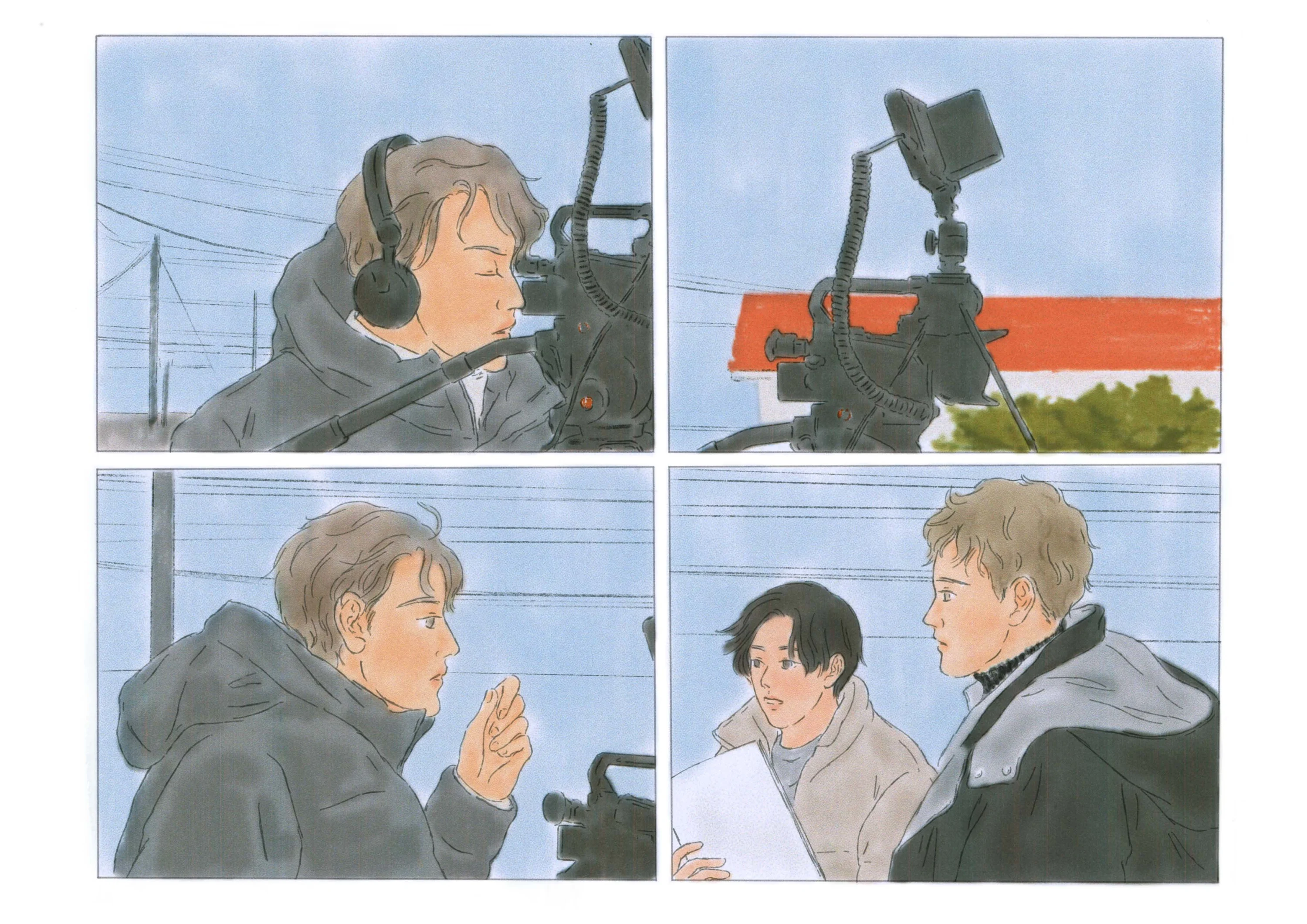

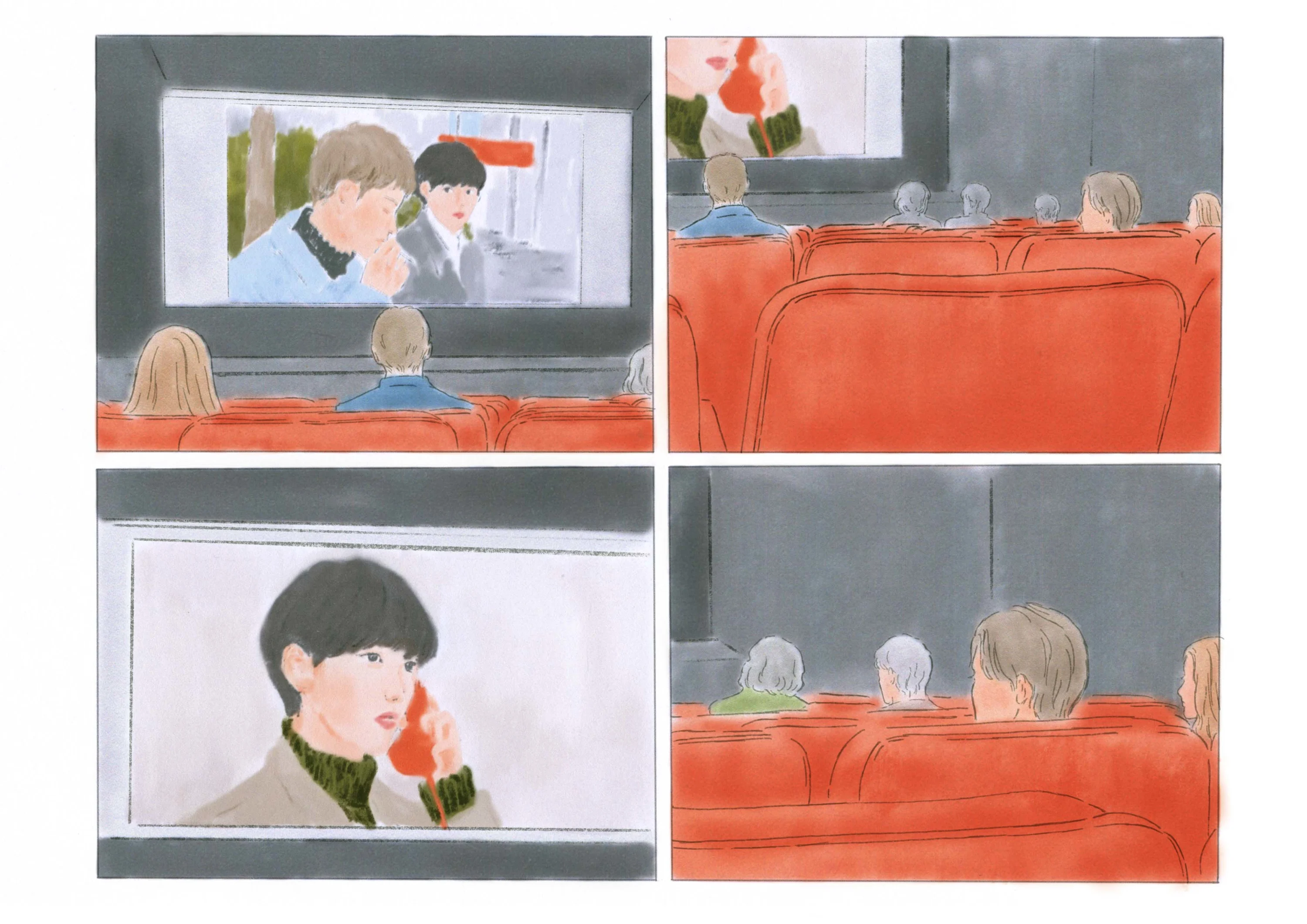

Artwork by Sun Bai.

I always feel intimidated during those five-10 minutes when the credits roll at the end of a movie. Executive producers, regular producers, key grips, best boys, DOPs, hair and makeup specialists, VFX producers, stunt people, music supervisors, heads of finance, accountants, catering teams, retouchers… Each production seems to require the establishment of a brand new staff at least two to three times the size of most small companies, and the amassing of the kind of funds that could keep me living in extravagant style until my dying day. To be in the director’s chair then, and to take responsibility for those people, that cash, that final creative product, must feel like an intimidating task, particularly when you’re starting out.

Emma Seligman, whose debut feature, “Shiva Baby,” was released to critical acclaim in 2021, talks openly in interviews about the impostor syndrome she felt while shooting the movie. She told Refinery29: “I called my friend Annie who had directed her first film a year before me…and I was like, ‘I can’t do this. I don’t know why they’re going to listen to a child telling them what to do.’ I had a panic attack and was like ‘We need to cancel the movie.’ We gathered all this money, all these people are here, and now I’m not going to be able to direct them.”

Ultimately, of course, she got it done, initially shooting the most intimate scenes with the smallest number of cast and crew and gradually increasing the number of people on set as her confidence grew. By all accounts the technique worked. The film was beloved by critics and audiences alike (it has a very respectable 96% on Rotten Tomatoes) and has led to plenty more opportunities for its director and cast.

But we’re getting way ahead of ourselves. Before Seligman could even take her seat in the director’s chair—in fact, before any director is able to start the film rolling—there are an awful lot of steps that need to be taken first, from script-writing, casting and financing, right back to simply developing a concept for a film. For some directors, the drive to make feature films arrives fully formed at college and doesn’t take too long to realize. (“Shiva Baby” started out as a short produced while Seligman was an undergraduate.) For others, the process is a little more protracted.

People would just laugh and say, ‘Oh, you guys are so creative. But what do you really want to make?’

Directing duo Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert—aka Daniels—have just enjoyed a few months at the epicenter of the movie industry’s press cycle promoting their sophomore feature “Everything Everywhere All at Once,” but their journey into movies was circuitous. “It was all just a slow-motion accident,” says Kwan of his working relationship with Scheinert. “I feel like we were collaborating with the algorithm: YouTube, Vimeo and Google were telling us we should work together.”

Kwan and Scheinert met while studying animation at Emerson College in Boston, and slowly, almost reluctantly, found themselves collaborating on projects, releasing camera tests and comedy shorts on YouTube and Vimeo, “without nearly enough thought or curation,” says Scheinert. One of their earliest, “Swingers”—a homage-in-the-loosest-sense to the 1996 feature of the same name—sees Kwan (as John Favreau) pushing Scheinert (as Vince Vaughn) on a swing until a strange accident causes their faces to switch bodies in an emotionally charged climax of mock-horror screaming. It’s puerile and they weren’t expecting much from it, “but people started to respond to it,” says Scheinert. then Vimeo chose it as one of their staff picks, “and we’ve just been chasing that ever since.”

Comedy shorts evolved into music videos and eventually people with budgets started to approach them to make commercials. Kwan stresses that there wasn’t a method or a plan; their first foray into music videos was done for free, “for a band that didn’t really need it because they’d already released a music video for the single two years before.”

British writer and director Raine Allen-Miller came to movies via a similarly indirect route. Having dropped out of an illustration degree, she took a job as a modeling agent, project managed some advertising shoots and eventually landed a role directing commercials at London creative agency Mother. But she found herself burned out from the pressure of advertising in her late twenties, and decided to use her recovery time to try something different.

“I had the worst breakdown of my life and ended up in hospital from the stress and the hours of doing advertising. I knew that directing was what I wanted to do, but the pressure of doing ads was killing me. So I wrote this short film that I didn’t think would ever come out, just because I felt the need to write something for myself. I sent it to a friend, someone whose opinion I really value, and they told me it was terrible and I just thought, ‘Fuck you, I’m gonna make it.’”

The short, “Jerk,” traces the story of an elderly Jamaican man living in south London who begins to struggle with his mental health, all the while maintaining a sunny facade to his friends and family. It premiered at the London Film Festival and led to Allen-Miller’s first feature film, but it wasn’t an easy process to get the thing made.

While she had experience writing commercials, Allen-Miller had never touched screenwriting before and she wasn’t entirely sure how to approach the process. From her time in advertising, she had a contact at the BBC who liked her first draft, and told her to send her script to Film London, where it was picked up as part of a young writers program. Programs like these are set up specifically to support aspiring filmmakers in the early stages of their career, and offer mentorship from experienced producers and writers to help get debut projects off the ground.

For Allen-Miller, this support was vital. Having never worked with characters and dialogue before, she was used to seeing her actors as props to move around a set. “Directing for advertising really isn’t about stories and human beings and emotions,” she says. “It’s about a product, so the character aspect just isn’t as important. But without character development, you can’t really direct a film, so that part of the Film London experience was really important for me.”

Kwan and Scheinert also scripted their debut through a writers lab, sending the first draft of what they called a “superpowered corpse buddy comedy” to the Sundance screenwriters and directors lab to see if they’d bite. Like many of their previous career moves, it wasn’t one they’d planned in much depth.

“We weren’t technically doing any TV or film at the time,” says Kwan, “but we ended up doing a lot of general meetings with a lot of different production companies and studios, and everyone would ask us what kind of movies we wanted to make. Everything we’d pitch them was just so absurd and out there that there was no connection and the meetings ended up being like really bad first dates where you just know it isn’t going to work out.”

Eventually, after a heavy year of shooting music videos and commercials, the pair took some time out to write something of their own. “All of our music videos were us just jamming a story in,” says Scheinert. “Sometimes too much story. But we were itching to do dialogue and really get into the writing process.”

They set to work on a revenge hostage musical penned specifically for Jackie Chan—working title“Codename Operation Heist-school the Musical…4?”—which sadly never saw the light of day. But the second script they wrote captured the imagination of a producer at one of their regular awkward meetings. It would later become their debut, 2016’s “Swiss Army Man.”

Everything we’d pitch them was just so absurd and out there that there was no connection, and the meetings ended up being like really bad first dates where you just know it isn’t going to work out.

“We’d been pitching the idea in meetings for a long time,” says Scheinert. “But people would just laugh and say, ‘Oh, you guys are so creative. But what do you really want to make?’”

Then one day, nobody laughed. Instead, says Kwan, the producer leaned forward and very quietly and sincerely asked, “If you really want to make this movie, why don’t you have a script yet?”

“That bit us in the ass,” says Kwan. “And he kind of bullied us into writing one.”

The script got them into Sundance, where “we talked to a bunch of terrifyingly smart, talented filmmakers one-on-one about it,” says Scheinert.

“The more we talked about it the more interesting and philosophical it became,” says Kwan, and the farting corpse script evolved into something with real emotional depth.

For so many movies, this is where the story ends. After development, perhaps a script gets turned into a short, or a few producers show an interest. But nothing is certain until checks are written and deals are signed.

This is where writers labs and mentorship programs are vital for rookie filmmakers. For Kwan and Scheinert, having the Sundance seal of approval was the first step towards getting “Swiss Army Man” greenlit by a studio. The second happened around the same time, when their music video for Lil Jon and DJ Snake’s “Turn Down for What” went viral. Finally, Paul Dano and Daniel Radcliffe agreed to play the lead roles and the pair had a complete package (Sundance-approved script, plus viral video, plus two hot celebs) to show investors when asking for what Scheinert refers to as “a modest amount of money.” ($3 million.)

For Allen-Miller, financing happened slightly differently. While her short, “Jerk,”was entirely funded by Film London, the team behind her debut feature, “Rye Lane,” was already scouting for finance when she was approached for the job. After a year of development in which she “changed a lot” of the script, Allen-Miller sent it to another contact at BBC films, Eva Yates (now director of BBC Film), who was able to secure a portion of the funding for the film. The remaining money, which came from the British Film Institute and Searchlight Pictures, was secured by producer Damian Jones—a huge figure in the British film industry with more than 40 production credits to his name.

“Having someone like Damian around was amazing,” says Allen-Miller. “He’s just great at getting shit made.”

Directing for advertising really isn’t about stories and human beings and emotions. But without character development, you can’t really direct a film.

Of course, with money comes conditions, and once “Rye Lane” was funded, there were serious discussions about the team Allen-Miller could hire to make the film. Initially it was suggested that seasoned cinematographer Robbie Ryan would be brought on as the director of photography to take some of the risk out of working with a debut director. But Allen-Miller was confident that the collaborators she’d worked with for commercials would be more than capable of creating feature films. “I wanted to work with people who I knew would hear and respect me,” she says, “so everyone—hair, make-up, costume—were people I’d worked with on commercials. But I had to fight for that a bit and be like, ‘Piss off, I know what I’m doing.’”

Kwan and Scheinert also work with the same teams across their projects wherever possible, so the whole team gets to hone their skills and develop their craft together. “We’ve always done our best work following our own selfish interests,” says Scheinert. “And we really appreciate being able to work with our friends.”

So we’ve done the writing, the script development and the financing. We’ve hired the team, shot the movie and spent months in the edit. Now the film is ready to release, right? Well, not quite. The final stage in this laborious process is the test screening—the first time that anyone in the general public will get to see the movie. These rightly make first-time directors nervous. When Wes Anderson’s debut “Bottle Rocket” was test-screened, nearly all the audience left the theater before the credits rolled.

“I’ve never sat through a film and been so uncomfortable,” says Allen-Miller the test screening for “Rye Lane”. “It’s a comedy, so you need to hear the laughs, or it’s just going to be mortifying.”

Thankfully, the response was positive, and now all she has to do is wait for the general release. “I’m really nervous about that,” she says, then trails off a little bit. “Yeah. I’m really, really nervous about that.”

She needn’t be. If Kwan and Schneierts’ experiences are anything to go by, her feature debut will only open more doors for her. In fact, it already has: next up she’s working on a TV series with Two Brothers, the production company that made “Fleabag.”

Kwan and Scheinert are similarly overwhelmed, with three TV series in development, the outline of their next movie underway, and commitments to guest-direct various other shows—all jobs that came along before their latest movie was released. “It's a wonderful problem to have,” says Scheinert. “Tell everyone how hard life is when your movie's a hit.”