Music can act as medicine in times of unrest. In the spring of 2020 when writer Sharine Taylor watched news coverage of the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Regis Korchinski-Paquet and countless others at the hands of police, and the protests and marches that followed, she found solace in the nostalgic sounds of soca. Here she documents how this music has long been the sound of rebellion and imagination and explores how its qualities can be applied to how we approach the future moving forward.

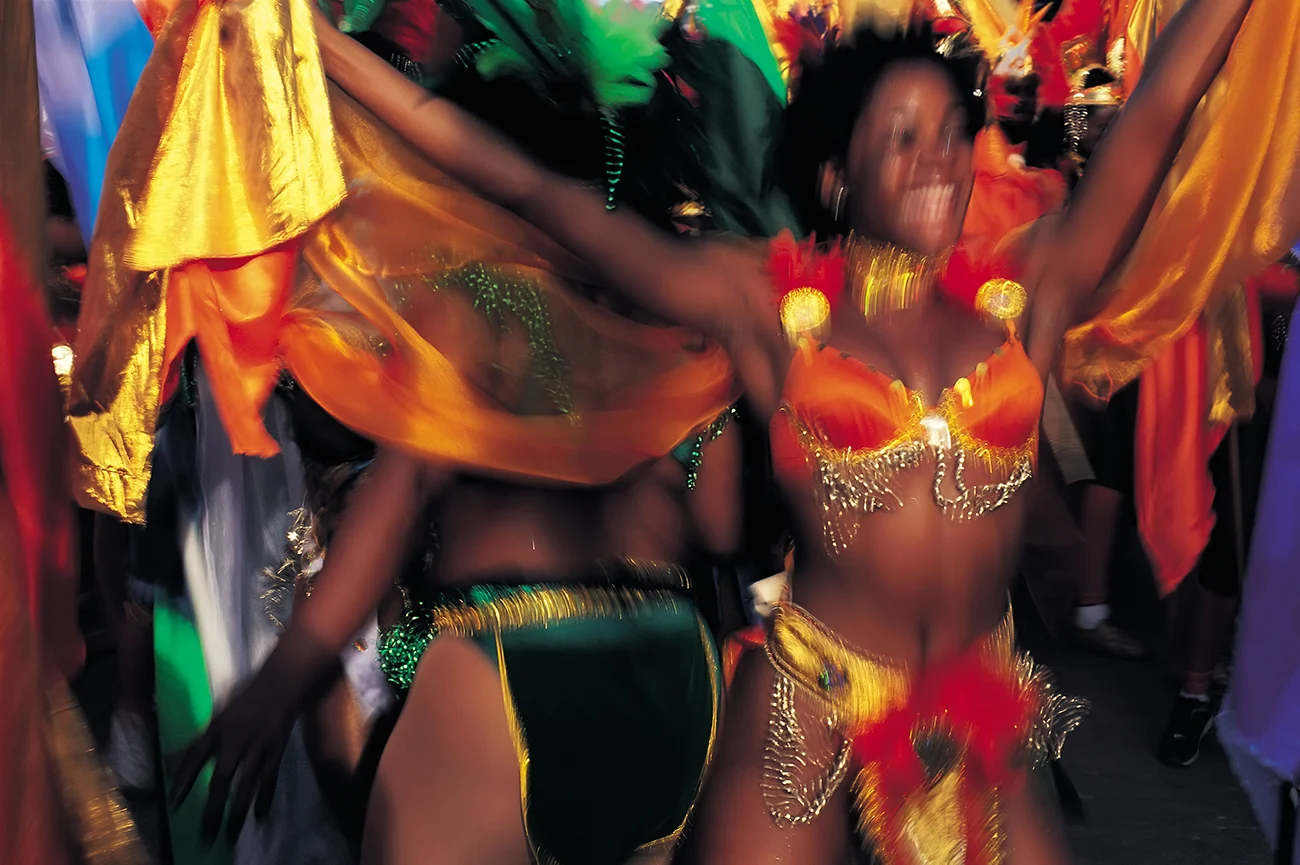

Cover image by Peter Adams via Getty Images

I spent May glued to my phone screen watching my timeline refresh with news and footage of the protests happening in my city of Toronto and across the nation in the US. Sparked by the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Regis Korchinski-Paquet and countless others, and in response to anti-Black racism and a storied history of police brutality, frustrations boiled over and people began mobilizing and demonstrating in their city’s streets. This was all in the midst of a global health pandemic that made otherwise bustling roads, avenues and boulevards bare. Calls for defunding and abolition were made and people righteously raged against the systems and institutions that failed them in a myriad of ways, prompting discussions on what a “good” and “bad” protestor looked and acted like.

While watching all of this unfold, I was grappling with something else. The weeks prior were spent coming to terms with a recently-cancelled trip to Jamaica for carnival and my response was to drown myself in the sounds of soca: a genre of music originating in Trinidad and Tobago but produced throughout the Caribbean that often scores carnivals in the region and its diaspora abroad. In an attempt to flatten the curve and limit the strain on an already-strained health care sector, Jamaica had closed its borders cancelling all major gatherings, and consequently postponing its carnival. Listening to my soca playlist was a means for me to cope.

Power soca, a highly-energized sub-genre with a faster BPM than its groovy soca counterpart, acted as something of a balm. The music I had been listening to would have been what I would’ve played for myself and my friends to get us pumped up before heading out on the road or to a fête (Caribbean parlance for a party). Trinidad’s Voice, Wuss Ways and Travis World’s Pandemonium had lyrics that said, “It’s a riot in here, oh Lawd/Man, I hope they can take this.” St. Lucia’s Motto and Barbados’ Fadda Fox teamed up to tell us to “shell dung dat.” Grenada’s Lil Natty and Thunda made calls to, “Get in your section, Get in your direction” on a record that shares the same name as its instructions.

Though crafted with carnival and fêtes in mind, there was an illuminating parallel between the energy in these songs and the energy I was witnessing in these demonstrations. Despite the obvious, differing, visual optics of Caribbean-originating carnivals and the protests that touched nearly every major city in the US and select cities abroad, they were all bound up in the same thing: Black liberation. With calls in contemporary soca to have “no behavior, total disorder” and to ramp up the bacchanal as a means to talkback to respectability, code of conduct and order, both the genre of soca and the traditions of carnival are a reflection and extension of the Caribbean’s own history of riots and movements that spoke to state-imposed violence and then-colonial rule. Understanding the roots of Caribbean carnival and listening to soca provided a soundtrack and means of digesting this pivotal moment of liberation for Black people in America and the world over.

Soca and carnival follow the traditions of Black cultural production around the globe. Born of circumstance, but bound up in rebellion and imagination.

For the unacquainted, carnival is a historic tradition that has evolved into the magnificent display of Caribbean culture – albeit commercialized – that we know today. People from around the globe, otherwise known as masqueraders, venture to their city of choice within the Caribbean region or a carnival in its diaspora to play mas in their colorful, dreamlike costumes, with massive headpieces on their crowns and marvelous, sky-kissing feathered backpacks. Masqueraders assemble themselves on the streets within their band of other masqueraders wining waists, dancing and losing themselves in unhinged euphoria with the sounds of soca powering their revelry. One can look to processions like Trinidad’s Carnival – aptly called The Greatest Show on Earth – or Barbados’ Grand Kadooment parade that wraps up its three month long Crop Over festival, to see exactly what the excitement of being on the road is all about.

Pageantry and glam aside, carnival’s roots are not to be forgotten. They were often forged by the fires of riots and resistance, were the product of celebrations of emancipation or chronicling the end of a harvesting season. Think of Trinidad’s Canboulay Riots: during the country's pre-emancipation period, freed colored people and French planters with then-enslaved Africans in tow participated in a ball. These balls involved its attendees wearing masks and the freed colored people and French planters mimicking each other from mid-December until Lent of the following year. After the British passed the Emancipation Bill in August of 1833, the country’s African-descended people decided to participate in a celebration of their own as a symbolic gesture of their newly-acquired status. Afro-Trinidadians kept particular elements of the European carnivals they witness – mimicry and masking are chief among them – but incorporated elements into their own iteration like calinda (stick fighting), added some traditional African practices like chantwells (a West African griot tradition which took the form of interactive call-and-response), but most importantly, they placed their celebration in the streets of the country and observed during the night opposed to confined spaces in the day like the Europeans did. This new practice was called cannes brûlées (which translates to “burning cane”), later anglicized to “Canboulay” to “commemorate the putting-out of cane fires during slavery” and the preamble for carnival as we know it.

With Afro-Trinidadians now mimicking the elite (this practise also birthed the creation of Carnival’s traditional characters like the Moko Jumbie and Trinidad’s Jab) tensions began to rise. Multiple laws were made overtime in an effort to curb its operations but that was met with little success. The newly-minted emancipation celebration was moved closer to European’s ball in February until 1880 when it was banned. On February 28, 1881, 150 police officers lead by Captain Arthur Baker, then-Inspector Commandant and chief of police in Trinidad for the British Empire, decided they were going to end Canboulay and in an attempt to cease its operation in what is now known as the Canboulay Riots: a bloody, three hour battle that resulted in a number if deaths and many injuries (to-date, this is still re-enacted every year as part of Carnival’s practise).

But from Canboulay came the emergence of the music genre kaiso which was the precursor for Trinidad’s social-and-political-commentary-filled calypso music. This also became foundational in the creation of soca as we understand it (some perspectives advance records like Lord Kitchener’s 1977 Sugar Bum Bum and Arrow’s Hot, Hot, Hot were soca before having been formally been dubbed soca), however soca had a slight twist. “You get in this party influence coming from what was happening in North America and that type of pop music influencing the calypso to become a more dance type music with commercial motives,” shares Dr. Kai Barratt, lecturer and carnival researcher at Jamaica’s University of Technology.

A record that I couldn’t erase from my mind was Ultimate Reject’s 2017 single Full Extreme whose infectious lyrics said “Di city can bun down, wi jammin’ still, wi jammin’ still/The building can fall down, wi jammin’ still.” Footage from the frontlines of the 2020 protests were bountiful in their expressions including rightfully angry people, but inclusive of those who were able to carve out moments of joy through music. Barratt contextualizes its lyrics with Trinidad’s social and political climate at the time saying, “There were a lot of things going on in the Trinidad and Tobago economy, the murder rate was quite high, crime was escalated and so on. This is how it was on the plantation. Things were bad, but they still found those spaces to celebrate and to enjoy themselves. This is still what we have and that is what soca does too.”

There was an illuminating parallel between the energy in the songs and the energy in these demonstrations.

MX Prime, one third of The Ultimate Rejects, didn’t originally pen his verse of the single with that kind of resistive interpretation in mind, but given that the pressures and the toll of living and existing under the thumb of capitalism, racism, classism and any other barrier that aims to keep us stifled, it does the same kind of labor. “This had nothing to do with destroying the party or anything like that,” he shares. “This was just about me feeling good about me! Celebrating my life. My fire was burning regardless of how you feel. It's not gonna stop me from feeling good about myself. It's not gonna stop me from fulfilling my purpose.”

For MX Prime, it was resisting the bad vibes around him, but for Jessica Baker, an ethnomusicologist and assistant professor of music at the University of Chicago studying the ethnomusicology of small island nations in the Caribbean, it’s part of an embodied spirit. “Caribbean music has always been about resistance in some way. There's always been a sense of music being one of the few ways that then-enslaved Black people and then-newly emancipated Black people could enact some sense of resistance against a particular kind of white supremacist, colonialist regime,” she says. “Even though music isn't necessarily actual, material liberation, it was a way for enslaved people to really take account of their own time.”

Knowing this, Nasty Up, a record by St. Vincent artist Problem Child, took on a whole new meaning. The powerfully exhilarant single starts off with punchy synths and a harrowing yell from the artist that commands the attention of anyone within earshot. “One setta crazy people jumpin up de band/All kinda different thing dey have in dey hand/Dey jumpin up and down dey doh give a damn/Carrying on like them is some hooligan...We go mash it up and buy back/Tear down and build back.” It wouldn’t have been uncommon to hear Nasty Up blaring from a speaker at a fête or during the road march to get masqueraders charged up for the remainder of their route ahead, but with the protests at the forefront of my mind it reminded me of the conversations about the politics of protesting and looting. The shedding of behavior and decorum that would be called for in a j’ouvert (a street party that begins at night and spills into sunrise of the next day with powder, paint or oil) was the same politic that informs the varied ways of any given protesters expressions.

Soca and carnival follow the traditions of Black cultural production around the globe. They were born of circumstance, but are bound up in righteous subversiveness, rebellion and imagination, and is that not what’s required when we think about a future where all Black lives matter? Watching the past few months unfold was, admittedly, daunting. Hopelessness often lingered in the air, but I remembered the spirit of resiliency that was part of what powered the movements of the past to lay the framework for the future. Though geography separates the location of these movements, it’s all an extension of the same Black politics for life and for liberty.