Thanks to the impact of British colonialism, artist Sinalo Ngcaba remembers her upbringing in the coastal South African city of East London being “very English.” In response, she chose to soak up and celebrate elements of Black culture, all of which she brings together in the energetic worlds she creates with her pastels and paints. She tells writer Yaya Clarke that she hopes to offer some “much-needed escapism” by finding new ways to depict Black joy.

After a deep dive into the Instagram profiles of many of today’s emerging artists you will find a chest full of artworks portraying well known figures. South African artist Sinalo Ngcaba’s genesis is the same, with a series of digital works made in 2020, depicting the likes of George Floyd and Black power figure Kathleen Cleaver. “As an artist it’s my responsibility to talk about what’s happening,” Ngcaba says. And the last two years have changed nothing in the way of concept, but everything in style. With a master stroke she lends her pastels, paints and ink to bolder and broader representations of Black life. “I decided it was better to take an icon’s pose and give it to ordinary people,” she explains.

Raised by her grandmother, who was a nursery manager and freedom fighter during the apartheid, she was exposed to an especial mix of art materials and human rights. “Maybe that’s where I get it from,” she says. After laughing at her home province being often mistaken for the United Kingdom’s capital, she is serious about the effects of British colonialism on her upbringing.

“My childhood was very English without ever going to England,” she reveals, a reality that led her to soak up Black music and art from around the world, and present us with the one she’s built in her practice.

Growing up in the eastern cape city of East London, she describes her hometown as "small”, and her exposure to institutional art even smaller. But that only grew her affection for the small town painter, small town sculptor and small town maker. In the piece “Just Me and My Beach,” a woman with a blue painted face is seen sitting on a chair in a body of water no larger than a splasher pool, oblivious to her surroundings on fire.

Ngcaba describes this as “much-needed escapism” for Black people worldwide. The painted face becomes a growing theme throughout her work, with tribute to the Xhosa people and their use of Letsoku (red soil) for cosmetics, art and symbolism. “I use it [in my work] as a sunscreen, but with more playful colors,” she says.

For Ngcaba, commissions and personal work hold no thematic difference. Recently creating the promotional artworks for Native Sound System’s debut album NATIVEWORLD, she uses Nigeria’s seasons – harmattan, rainy and festive – as a backdrop, further showcasing the painted face as both a literal protection from the elements and metaphorical shielding from the troubles of the outside world.

For Ngcaba, this is all in alignment with her purpose of sewing counter representations of Blackness into art, after years of seeing Black suffering throughout visual media. “I’m building a world of joy outside of our pain,” she says. On the Native album cover, she combines the seasonal themes and connects the figure’s hair to the clouds, toying with our perception of background and foreground, all in the effort to “build a completely new world for the album.”

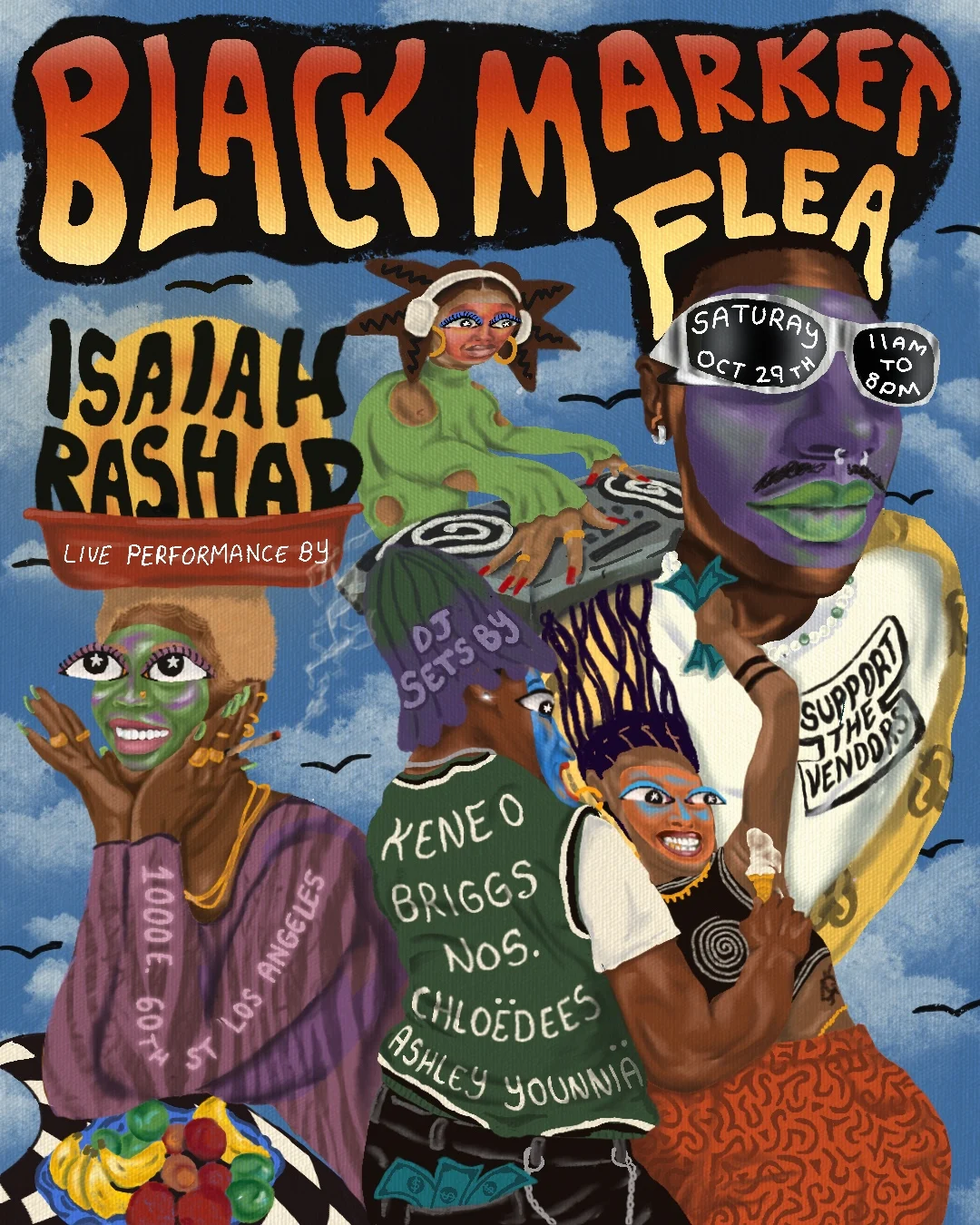

Like many creatives today, Ngcaba’s beginnings included an internship, a crack at a career in advertising and a soul-destroying corporate job. Much of this work was futile to her artistry, but it was a life jacket, and now she has a growing list of clients including Comedy Central Africa and Nike. Recently illustrating a second poster for Black Market Flea, she’s further built her relationship with the Los Angeles based community (that started with a direct message on Instagram), and their event partner Frequency, leading to commissioned work from the internationally touring day party, Everyday People.

This experience informs Ngcaba’s philosophy of “put your best work out there.” She describes being able to create the “intentional work” in the past year as something that is only possible with sharing and “making work that’s true to you.”

When explaining what it’s like to create “intentional work that aligns,” she opens up about treading the line between passion projects and earlier briefs that warped her artistry and morals. “When I started, a lot of brands would see my style and ask me to apply it to their ideal. I still took the jobs even when our morals didn’t align, because I needed to. But now I’m fortunate enough to only say yes when it’s right.” And when it comes to pricing her work she experiences a dilemma with her audience that may not be as easy to solve: “I price my work quite low, because people who most appreciate my work can’t afford to buy art. I can’t afford to buy art!” she says. Ngcaba describes this as “unfortunate” but sees it as a lesson for emerging artists to consider client-based work and build relationships with those that have a similar mission.

Now living in Johannesburg, she’s surrounded by a heap of diasporic districts and a booming art scene. A shift that has also taught her that for people like those in her hometown, the only way into the art world—that “pretentious and elitist” world, as she calls it—is to play the game. But Ngcaba has her own game plan and high hopes for the future, hoisted by the internet, Black culture and her ever growing motif.