Painter Shirley Villavicencio Pizango grew up between Lima and a small village in the Peruvian Amazon, but spent much of her adult life in Ghent, Belgium, and it was that separation from her home country that allowed her to fully appreciate its beauty. Her work is influenced by her experiences in these two disparate places, with many of her abstracted subjects depicted before colorful backdrops filled with flora and fauna. She tells writer Chloë Ashby that she’s responding to the way art has historically exoticised and subjugated people of color, by painting people with darker complexions posing with pride and strength.

There’s a reason why some writers leave their books in a drawer for a while after finishing the first draft. Space away from something—away from anything, really—lets you see it with fresh eyes. When it comes to her intimate portraits of family and friends, Belgium-based Peruvian artist Shirley Villavicencio Pizango often works on several paintings at once, giving them room to breathe and herself time to reflect. “I’ll leave one to rest for a few days while I work on another,” she says, “and then, when I return to the first, I’ll have new ideas and be ready to go again.”

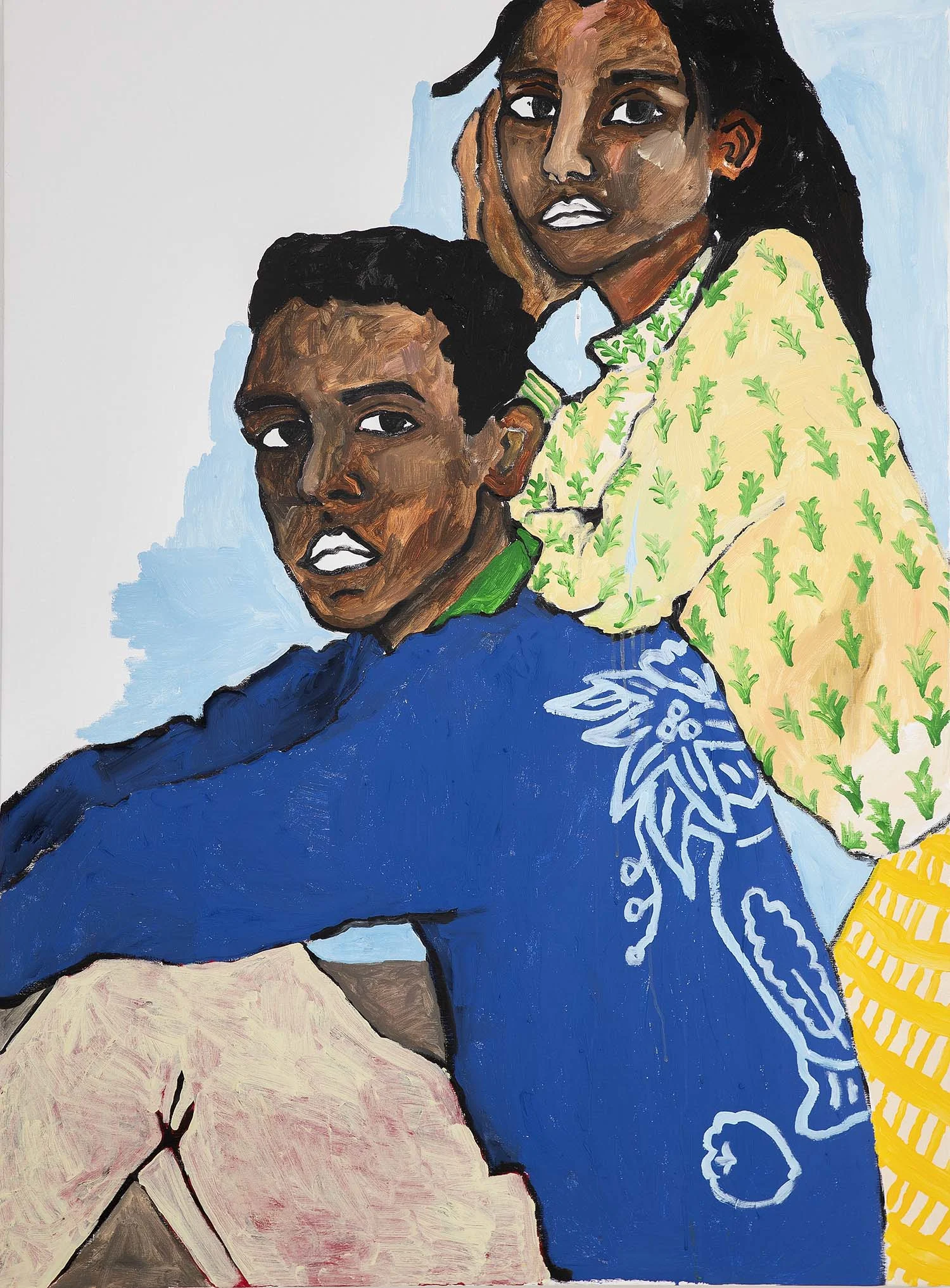

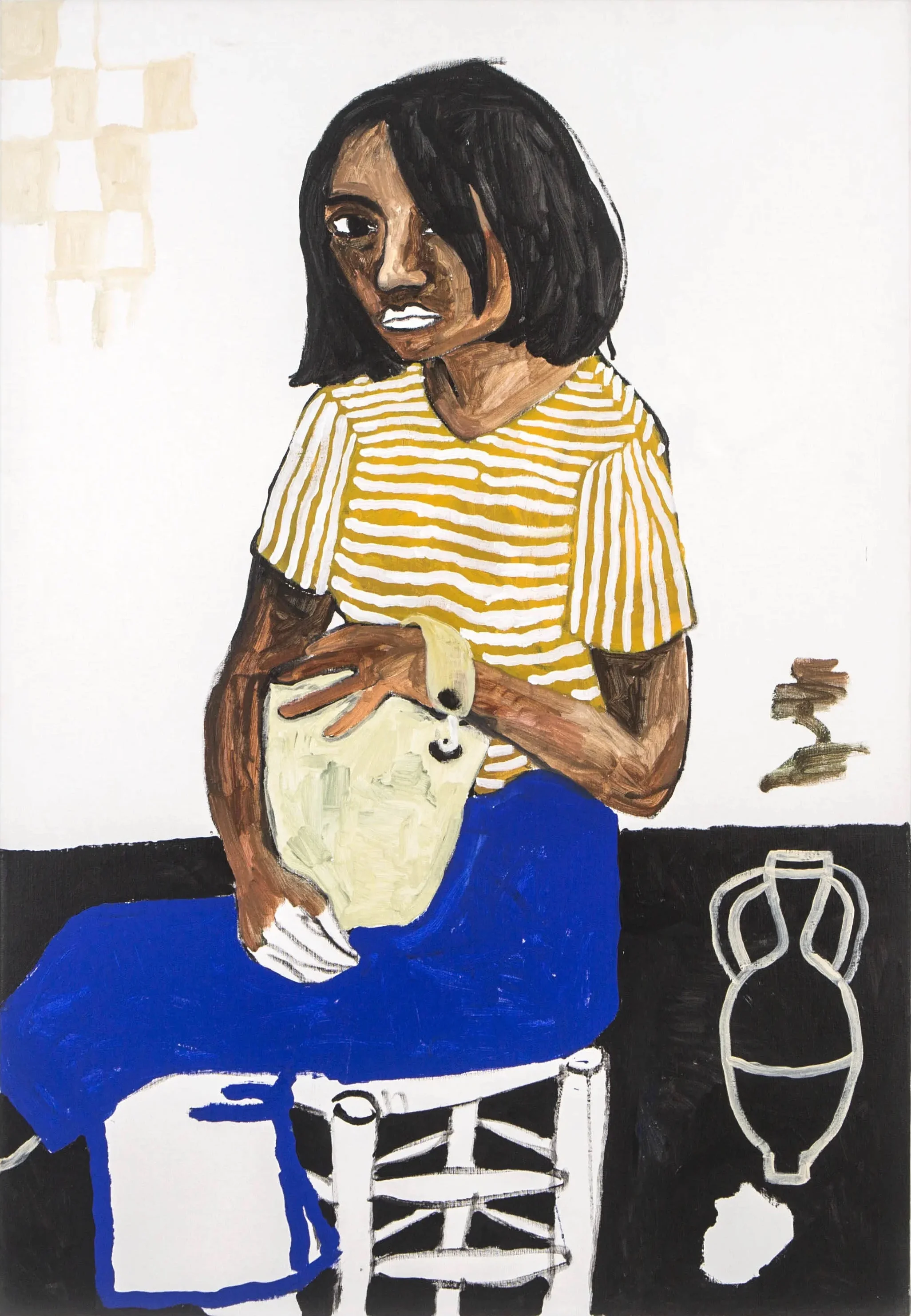

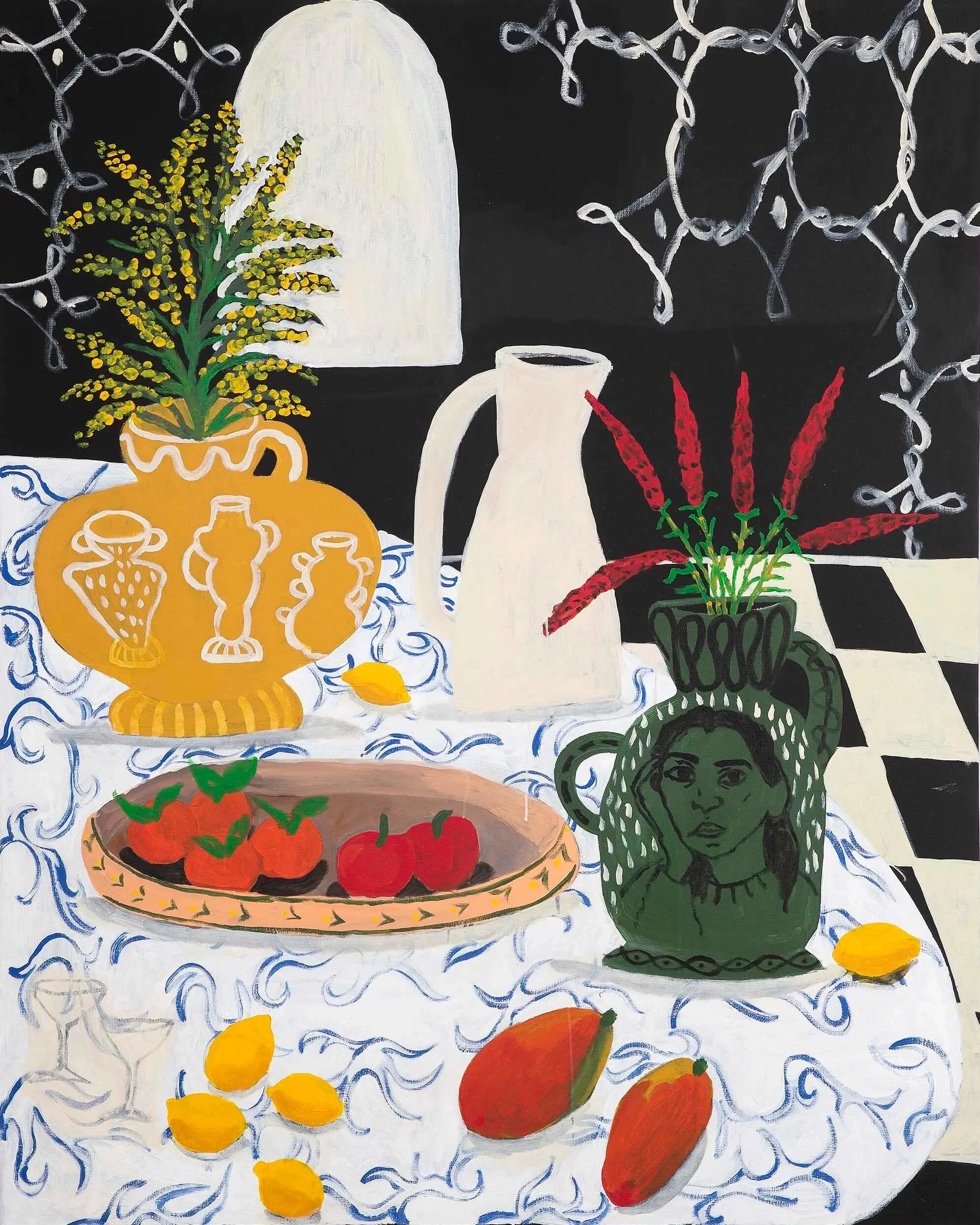

Right now, as she prepares for a solo show at Steve Turner in LA, her studio is filled with works-in-progress. Dark-skinned faces beam out from conspicuously blank canvases. Typically, they belong to fellow Peruvians and other people of color, their skin composed of subtly graduated shades. “I like to start with the face, partly because I’m often painting from life and I want to get it done before the sitter starts talking,” she laughs. Next come vibrant clothes and the inklings of an imagined background: decorative wallpaper, geometric tiles, lush greenery, potted plants.

Shirley was born in Lima, Peru's capital, and grew up between there and Santiago de Borja, a small village in the Peruvian Amazon. She was raised Catholic, with a strict sense of right and wrong. When she was 18, she moved to Belgium to study law—a respectable choice, according to Peruvian convention. “Belgium opened my eyes,” she says. She became close with a family who, for the first time, asked what she wanted to do with her life. “I told them I wanted to be an artist.”

I’m aware now of the power that I have as an artist when it comes to representation.

In the same way that stepping back from a canvas helps Shirley see it clearly, distance enabled her to take a more objective look at her home country. She appreciated its flora and fauna, bristled against its unattainable beauty standards, and realized just how conservative her upbringing was. Thrown into a new and more liberal way of life in Belgium, she grappled for a sense of belonging.

This crossover between her childhood in Latin America and her life in Europe plays out in her work, which marries a Peruvian palette with a Belgian way with words, as she uses language to subvert a straightforward reading of her paintings. “When someone sees them, and how bright and colorful they are, they assume they’re happy,” she says, “and then they read the titles.” For example, “Shadow of Absence” (2019) draws attention to the male figure at the center of a group portrait, his face ghost-like and obscured. The atmosphere of “Promise You’ll Come Back” (2021) shifts from tender to apprehensive when you notice the slender arms of one woman clinging tight around a younger girl.

It was after completing her masters in Belgium that Shirley landed on her style: candid portraits that toggle between realism and abstraction. Oversized men, women and children sit and stand in front of flattened backdrops, from domestic interiors to the great outdoors. As in old master portraits, they’re accompanied by still lifes: bulky ceramics, glossy clementines with waxy leaves, a scraggy cockerel. She has an affinity with Matisse’s use of color, and his ability to create solid images with just a couple of lines, and appreciates Picasso’s zest for painting everything in his life.

There’s a frankness to Shirley’s work, which is partly a result of the way in which they’re painted—directly onto the canvas, with loose strokes. “I like to be spontaneous and to play,” she says, hence her preference for fast-drying acrylic. Some portraits consume her for days, while others are completed within a single sitting. Many teeter on unfinished, among them “Memory of a Forgotten Future” (2021), with its stunted tiles, patchy wicker stool, and unpainted fingers. Somehow, such gaps enhance the sitter’s wholeness.

I want to represent my people as proud, to show their worth.

It’s the gaps in the so-called canon that Shirley seeks to fill. “I’m aware now of the power that I have as an artist when it comes to representation,” she says. “It wasn’t something I thought about in the beginning; I was just painting what I knew.” As soon as she began to engage with the history of art, she noticed the sense of pride afforded to white westerners versus the exoticism and subjugation of people of color. “I want to represent my people as proud, too, to show their worth.”

Which is why the women in her portraits are almost always clothed. When she does paint a nude, it tends to be based on herself. During the making of her first self-portrait, she caught herself thinning her face and lightening her skin tone. In time, she stopped worrying about what other people think. “I began to paint for myself, and to paint bigger and bigger,” she says. “It’s OK to be a muse, but women aren’t only muses—we’re also people who think and who act and who are strong.” “Tame the Horse, Ride the Power” (2020) shows a bare-chested woman astride a steed, her torso turned towards the viewer, her gaze fixed firmly on ours. The portrait is based on a photograph of Putin, and it was part of an exhibition named “A Tear for Power,” about how narcissism is something most often associated with men. “I put a woman in the place of this narcissistic leader, giving her the power of a man,” Shirley says.

That woman on the horse could be Shirley, but contained within her gaze is the same sense of determination found in all her sitters. In her art, she wants to tell another side of the story, to shift power into the hands of others. Her biggest hope is that people—and above all children—see themselves in her paintings. “I start with the personal, but by the time I’m done with a painting I hope it’s universal.”