How does one gain the nickname “The Bead King”? Sanaa Gateja knows all too well, as he’s long been called it in his home of Uganda. Sanaa is a mixed-media artist and jewelry designer, known for his use of recycled and sustainable materials – largely paper beads – to create large-scale, intricate works that send messages of hope for our environment. Writer Sarah Souli hears his story, and learns about the incredible impact he’s had on the arts and crafts movement in East Africa.

Images courtesy of Afriart Gallery.

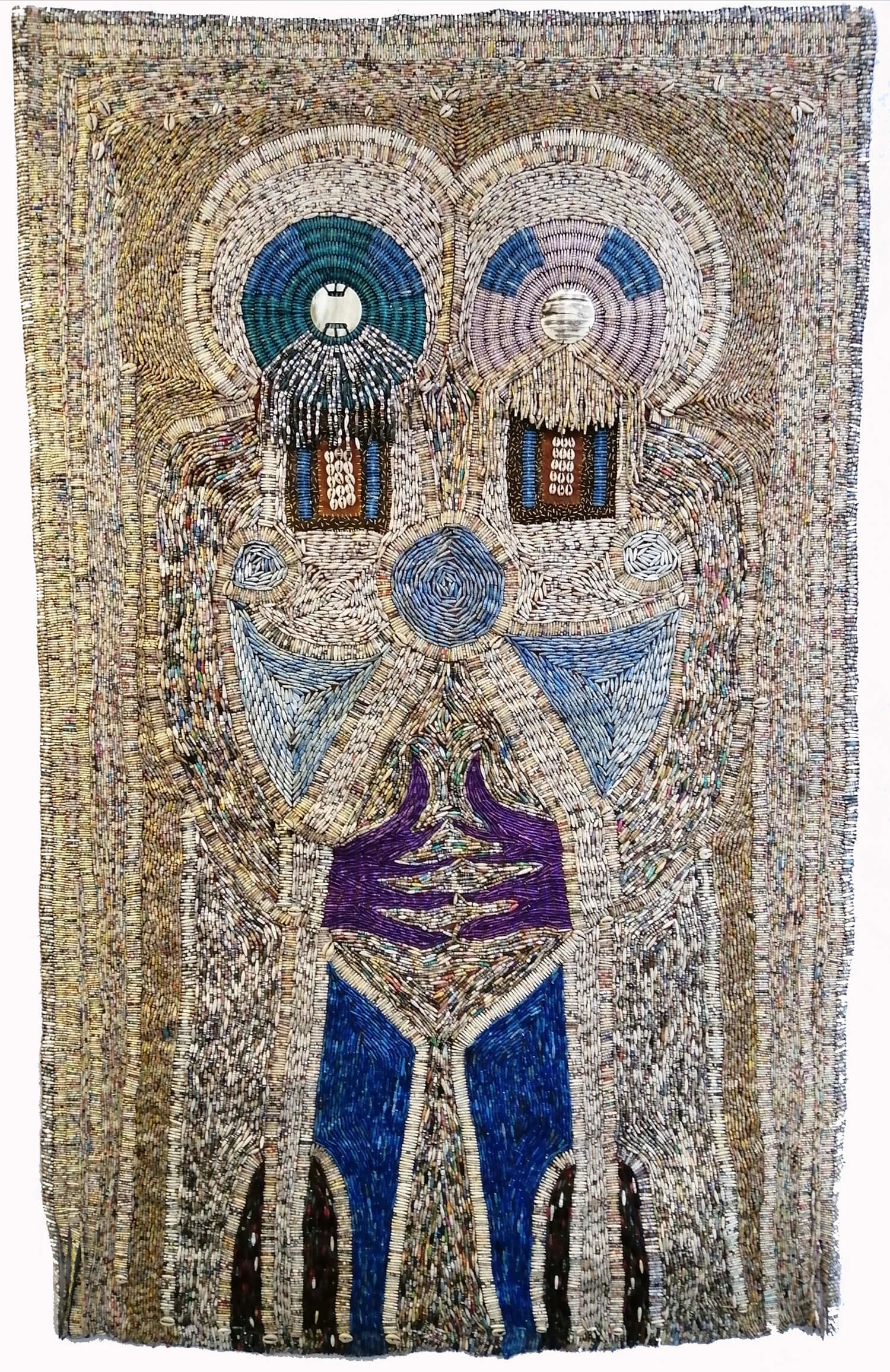

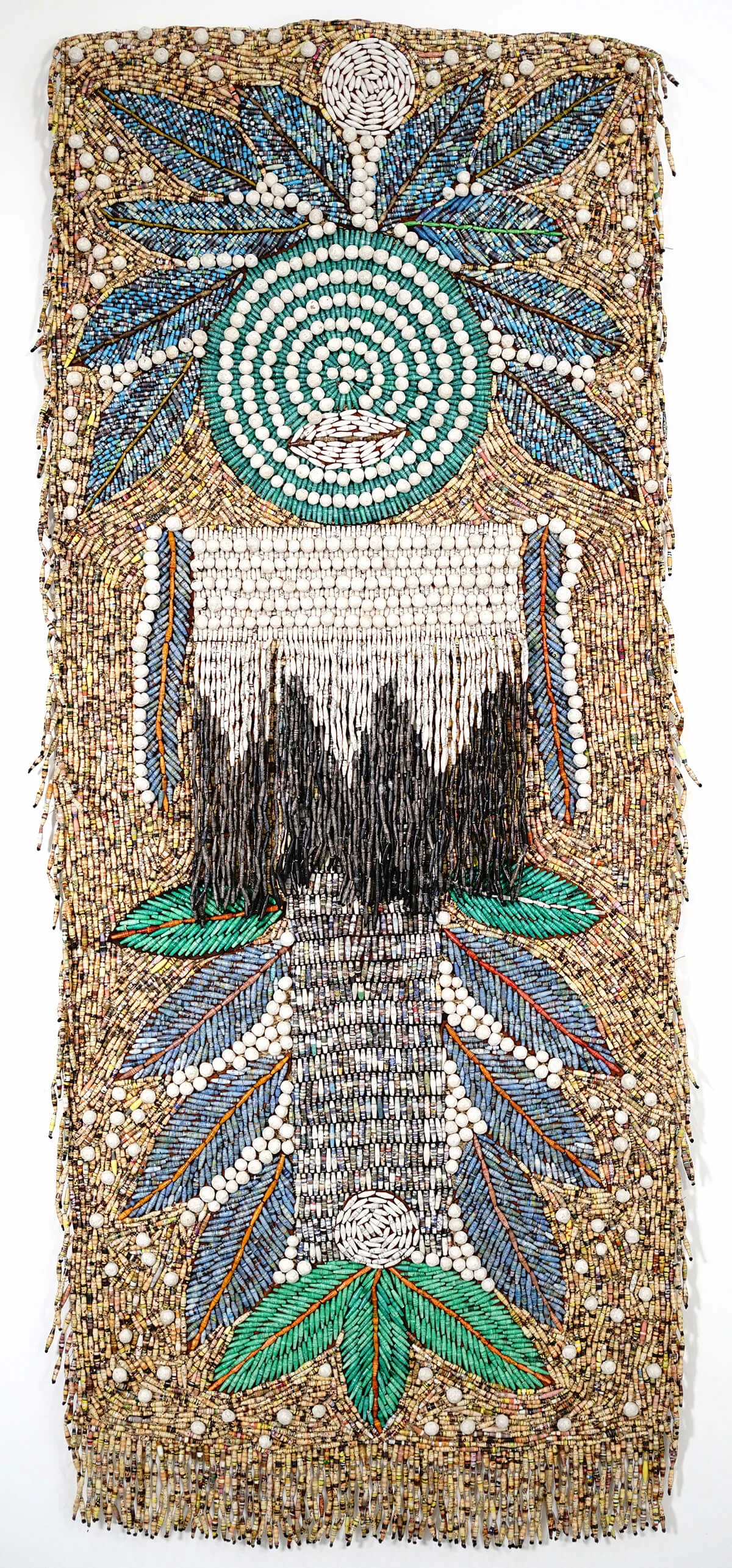

“In all traditions, especially African, a bead is a tiny sculpture with a unique form whose purpose is to keep and preserve messages within the material,” says Ugandan mixed-media artist and jewelry designer Sanaa Gateja.

As an artist, I want to discover secrets within materials.

Magatama Japanese beads, Islamic glass beads, Mauritian Kiffa beads, Tibetan dzi beads, Native American Heishe beads,Nigerian powder glass beads—humans, nearly everywhere in the world, have long had an affinity for beads. Multi-functional in their essence, they’ve been used as jewelry, decoration, currency, games, calculators, anti-tension devices, or for religious purposes (like the melodic, meditative snapping of beads on an Eastern Orthodox komboloi).

Known as the “Bead King” in his home country, Sanaa has been working with beads for decades. Born in 1950, 12 years before Uganda would gain its independence against its British colonizers, his first encounter with beads was on the people around him: men, women, and children who adorned their limbs with these small, shimmering sculptures. “I was fascinated by their power and beauty,” he says, and an obsession was born.

Now 72 years old, Sanaa continues to have a prolific career, and is considered one of Uganda’s most important living artists. His large-scale, intricate multi-media pieces are primarily made from colorful, recycled paper beads and bark cloth, and have both a social and environmentally positive impact. “I’m a self taught artist who rejected the way art was and still is taught in our schools and institutions, so I looked back at our traditions and skills,” Sanaa explains. That backwards glance, particularly the attention to craft, is tangible in his pieces. While the tiny beads that make up his tapestries and hangings shape-shift in front of the viewer’s eyes, taken in as a whole the works are undeniably powerful.

We had a vision to spread the message of creativity and awaken the sleeping giant that had fallen under colonialism.

Art and craft are tightly interwoven in Sanaa’s work, and the delineation between the two forms feels purposefully non-existent—it’s natural, then, that Sanaa got his start in the late 1960s, working for the Ministry of Culture, where he was sent to manage their crafts shop in Uganda’s pavilion at International Expo in Osaka in 1970. A year later, at only 21, he opened Mombasa's first art gallery, in the city's Old Harbour. With an eye now fine-tuned for the intersection of art and craft, he began selling objects and works primarily from the East African coast, highlighting artists and techniques from countries like Tanzania and Somalia. Encounters with European tourists who were searching for interior designs with “African accents” led to commissions, which prompted a deeper self-study into design and art history.

“The more I saw myself as an artist, the more I saw myself as a designer,” Sanaa says of that time. By 1982, itching to explore more, he had sold his gallery, and took his wife and two children with him to Florence, where he spent a year studying jewelry design before moving to London. It was the early years of the British Black art movement, a radical political art movement that boldly highlighted and promoted the work of Black artists, and it was a profoundly exciting and historical moment.

“The minority communities in London were lobbying for recognition and funding for a better life,” notes Sanaa. “I joined the Black art movement, and our exhibition in 1985 New Horizons at the London Festival Hall was a great success. The politics in Africa influenced us to look back and see where we could contribute as artists.”

History was also in the making back home in Uganda. In the early 1980s, the country was going through a civil war, and the same year as the New Horizons exhibit, a military coup d’etat overthrew President Milton Ubote. It was also the year Sanaa opened Safari Studios, a gallery to exhibit his work and that of other artists within his circles. The name had a double meaning: “I called it Safari Studio because I had decided to return home when I was ready, and this was the project to facilitate my going,” he explains.

The ticket home came from an unlikely source: paper. Uganda has a rich tradition of recycling, and back home, Sanaa was used to seeing recycled products from rubber, metal, plastic or paper. But the sheer amount of waste paper in London – from advertisements, letters, bills, leaflets, newspapers, magazines – was astounding. It was also a breakthrough moment. “As an artist, I wanted to discover secrets within materials sparked by the carelessness of the way modern people handle their waste and our destruction of the environment,” says Sanaa.

At the time, Sanaa was making beads cast in gold or silver for his jewelry clients in Europe. He knew this wouldn’t be tenable back in Uganda, where precious metals are exorbitantly expensive—but recycled paper was not. Long driven by the power of community, Sanaa searched for a way to connect local Ugandans with his artwork. Along with his close friend, Nigerian-British artist Joseph Olubo, Sanaa formed Kwetu Africa (kwetu is the Swahili word for home.) “We had a vision of spreading the message of art and creativity, to awaken the sleeping giant that had fallen under colonialism,” he says.

Though Olubo passed away in 1990, Sanaa was able to realize their shared dream. He returned to Uganda and began training a group of 10 young men and women to work with local materials like bark cloth (which is traditionally used to embalm the dead), bamboo, and recycled paper to make ornamental items, particularly beads. By actively engaging the local community, Kwetu both elevates the creativity of the individual and also provides structural, economic support: people, mainly women, are taught to make paper beads to generate their own income. The process is simple enough that once trained, artisans can pay it forward and teach others in their home towns and villages to make paper beads. Sanaa estimates that 100,000 people have been impacted through Kwetu, and in 2016 he was awarded the Bayimba Honours for philanthropic work.

Today, paper beads are a cottage industry in Uganda, but Sanaa has also elevated them to another artistic level. Utilizing his pioneering method for making beads out of paper (glossy Chinese propaganda magazines were abundant in the 1990s), Sanaa evolved his artistic practice, incorporating beads into his multi-media work. Sometimes the paper itself carries meaning, like a half ton stock of 2008 Obama campaign materials that were destined for the shredder. Instead, it was sent to Sanaa, and the ensuing “Obama Beads” were exhibited at the Museum of Art and Design in New York in 2010.

But most of Sanaa’s pieces are more universal. Largely experimental, his abstract pieces touch on themes like nature, family, nourishment, and caring, all important facets of cultural life in Uganda that still transcend national boundaries. Sanaa’s pieces also seem to echo his own ethos. On its own, each bead is beautiful but nothing more – their true power and beauty comes from the collective.