Rui Tenreiro was a boy when the Civil War in Mozambique finished in 1992. “Growing up it was quite an isolated country,” he explains. “It was very hard to get cartoons or comics or music.” After the war, all sorts of influences started to flow in as the country opened up, and for the young Rui, it changed everything.

“When I was finally exposed to something like Japanese anime, it was like wow. What is this?! The same happened when I came across a copy of A Clockwork Orange in my local video shop. I think I was 11 years old and I don’t think my parents knew that I was watching it.”

These formative experiences grew into an insatiable appetite for new things, Rui believes. In his career he has worked as an art director, illustrator, writer, publisher, puppet-maker, filmmaker and animator and he likes to be defined by this restless creative wandering. “I know I am not easy to sum up, and I am glad about that,” he says. “I don’t just want to do one thing and I get a lot of pleasure from discovery.”

At heart he sees himself as an art director, his first career when he left Mozambique to work in advertising in South Africa. His skillset, and his natural creative impulse, comes in zooming out to see the bigger picture.

“I am often bought in to create a world, a feeling of being inside something,” he explains. “I like when you are reading a book or watching a film and you have the feeling of being inside a particular world that is self-contained to that thing, whatever you are experiencing.”

When I was a teenager I didn’t know it was possible to make a living from drawing.

Part of creating these worlds is a focus on details, and craft, but he sees his role as more conceptual than that. “What I think is often overlooked is the emotional side of something – to always have in mind the emotional charge that is contained within a book or a film or a story. You have to be aware of that positive energy you can transmit.”

As a boy in Mozambique, Rui first turned to drawing, “when I realized I couldn’t play football to save my life.” He’d sketch little scenes and characters during break-times at school, but it was some time before he realised this could grow into a career. “When I was a teenager I didn’t know it was possible to make a living from drawing. That just seemed strange. It still does!”

After his stint in the ad industry he moved to the UK to study illustration, then to Norway with an ex-partner, back to Mozambique, and then to Sweden for a Masters in Storytelling. He’s been in Stockholm ever since – 11 years and counting.

Recently he has been drawn back to African themes and stories and believes the continent has rich creative potential, if you know how and where to look. “In Europe, commissioning an artist is easier,” he explains. “They have a portfolio and you have a good idea of what they are going to create. Often with African creatives, they have very interesting work, but you have to fish it out here and there – sometimes it’s on Facebook, sometimes it’s on Instagram or Tumblr. It makes it more interesting because you get things you don’t get anywhere else, so it’s more satisfying, but it’s more complicated too. It’s more like an investigative project.”

That said, he is quick to warn against thinking about Africa as a homogenous whole, especially when it comes to its creative scenes. For example in Tanzania, he explains, there is a very localized comics scene – katuni – with a locally-produced anthology that has been published since the 1970s. “They have created a stock cast of characters, and a very specific set of stories, about status and women and cars and wealth. It’s complex, but it’s very interesting to look at what’s going on in these different places.”

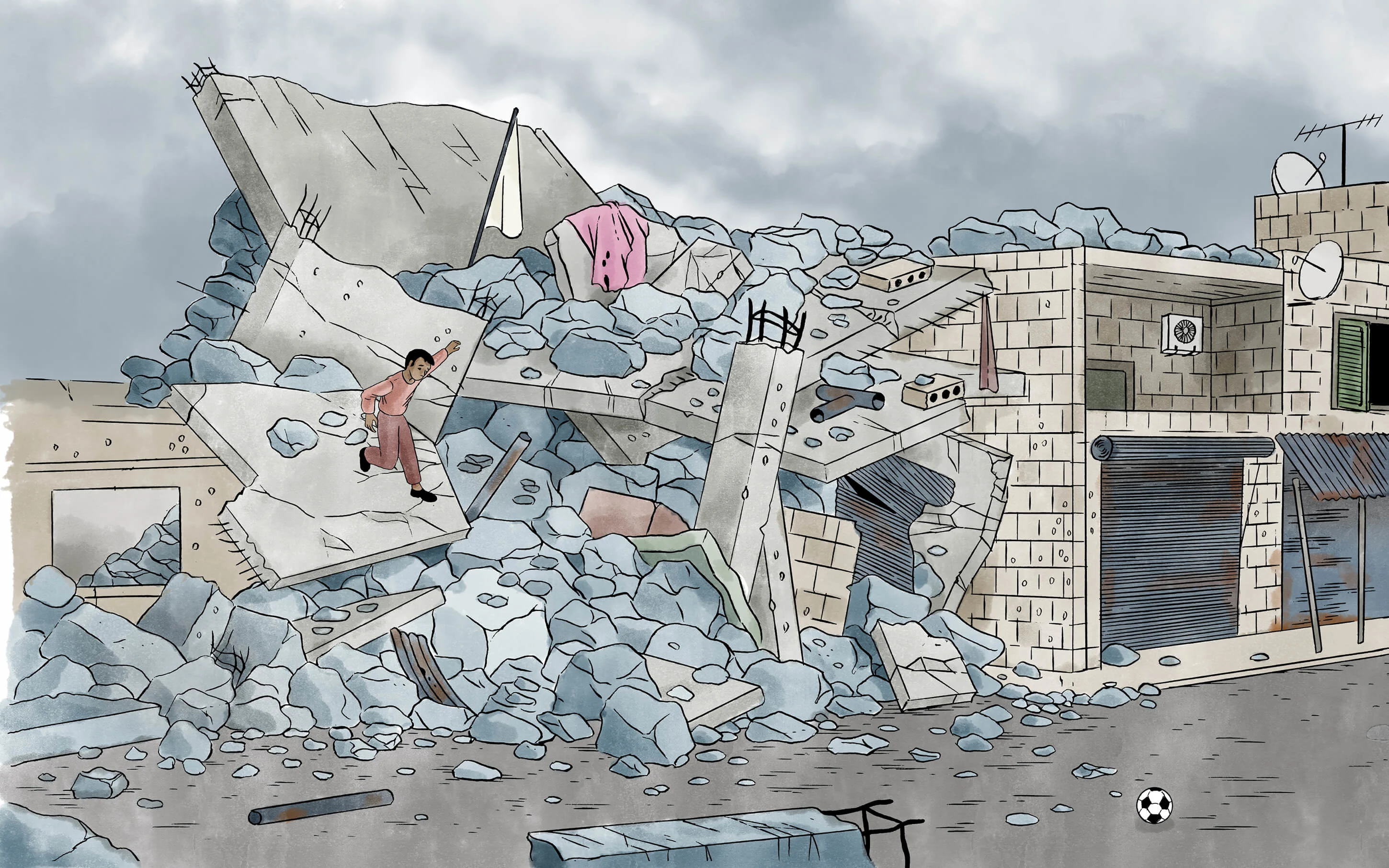

For one of his most recent projects – a 10-page comic in the July 2019 issue of McSweeney’s magazine – Rui turned his attention to the ongoing war in Syria.

Inspired by Albert Lamorisse’s 1956 featurette Le ballon rouge (The Red Balloon), Rui initially pitched the idea of a direct homage, with a red balloon floating over scenes of destruction. “But then we decided to remove the balloon – I am not sure if they were worried about copyright. We included a football instead, which I also think is hopeful, a positive symbol.”

That chance of a failure is something you have to accept from the outset.

The pictures are an unsettling mix of calm and chaos – quiet scenes of piles of rubble and buildings collapsed in on themselves. “The photos of Syria are just crazy,” Rui says. “There is something obscene about all that destruction, those piles of concrete. You can’t look away.”

He continues, “I didn’t really have any message in mind, I just thought it would be interesting to expose the readers to that. It’s not something I can usually do in a magazine, to delve into a story like this for several pages. Making every page this environment of destruction really emphasized the chaos.”

Across all the different projects he’s worked on, Rui has learned to focus on the things he can control and not waste time worrying about the things he can’t, such as how people react to his creations.

“It’s impossible to know what effect something will have,” he says. “It could be a success or it could be a failure, and that chance of a failure is something you have to accept from

the outset.

“When I was working on my last film, I turned to the director when we were close to the end and told him, you know, this could be a total flop. He just looked at me with terrified eyes, but it’s something all artists know.”

Words by Rob Alderson.