Trying to work through her complex relationship with her daughter Alice, photographer Siân Davey started photographing her. It led to the wonderful book Looking for Alice. Now, Siân turns her lens onto her adolescent son Joseph to explore their changing relationship.

It was Siân Davey’s acupuncturist who told her that when you do what you love, you’ll get the support you need. She believed him. She promptly packed up her 15 year long private psychotherapy practice and, in her forties, began her photography career.

She went on to study an MA and an MFA in photography. This is where she realized she’d been making pictures in her mind since childhood, but that taking photos allows her to reproduce these images for others to see.

Siân shoots life around her in Devon, England. Her intimate images center on family – mostly her own. “My family is also a microcosm for the dynamics occurring in many other families – all the joys, tensions, ups and downs that go with that territory of being in a family,” she says.

While pregnant with her youngest child Alice, Siân found out that she would be born with Down’s Syndrome. “Alice did not feel like my other children and part of my response was to pull away from her,” she says.

To counteract her initial reaction, Siân started photographing Alice from when she was one year old. The images capture Alice snuggling with her siblings, having her fringe cut and just being a little girl. “The result was that my fear dissolved, I fell in love with my daughter. We all did,” she says. Looking for Alice became her first photobook.

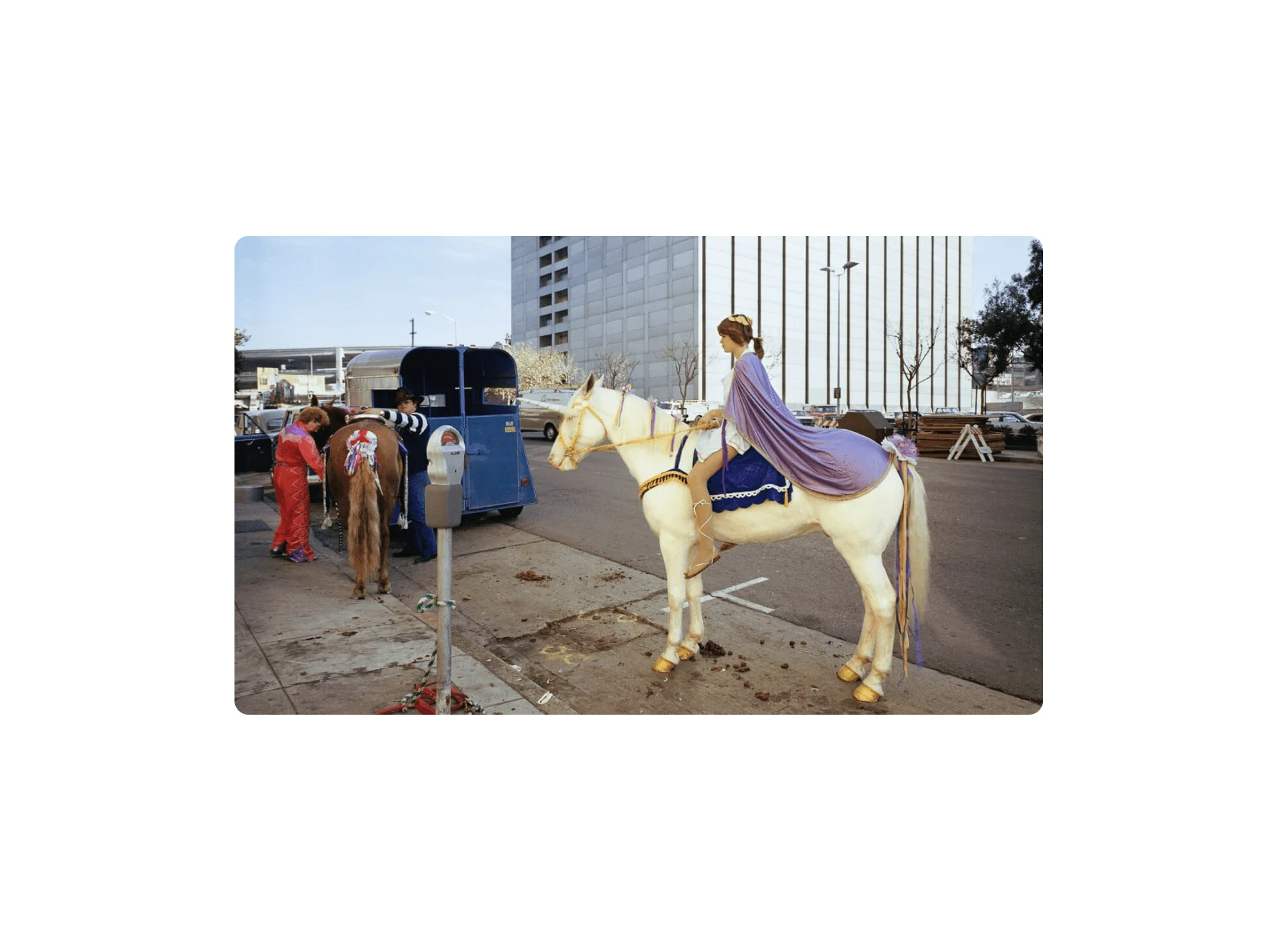

One day Siân’s 16 year old stepdaughter Martha asked why she didn’t take photos of her anymore. The enquiry launched a new project, simply titled Martha, which documents the teenager becoming an adult over the next three years.

Unusual for a parent-child relationship, Martha allowed Siân to follow her with her camera everywhere – when she met up with her friends in the park, went swimming in the river or spilled out of clubs in the early morning hours. The series captures bittersweet moments as Martha and her girlfriends grow up, begin dating and become young women.

Now she’s focussing her lens on her youngest son Joseph in his early years as a teenager. Each project she sees as a collaboration with her children. “I think there was an unconscious collaboration between me and Alice,” she says. “And with Martha, it was conscious, because of her age and the way that we spoke about the work.”

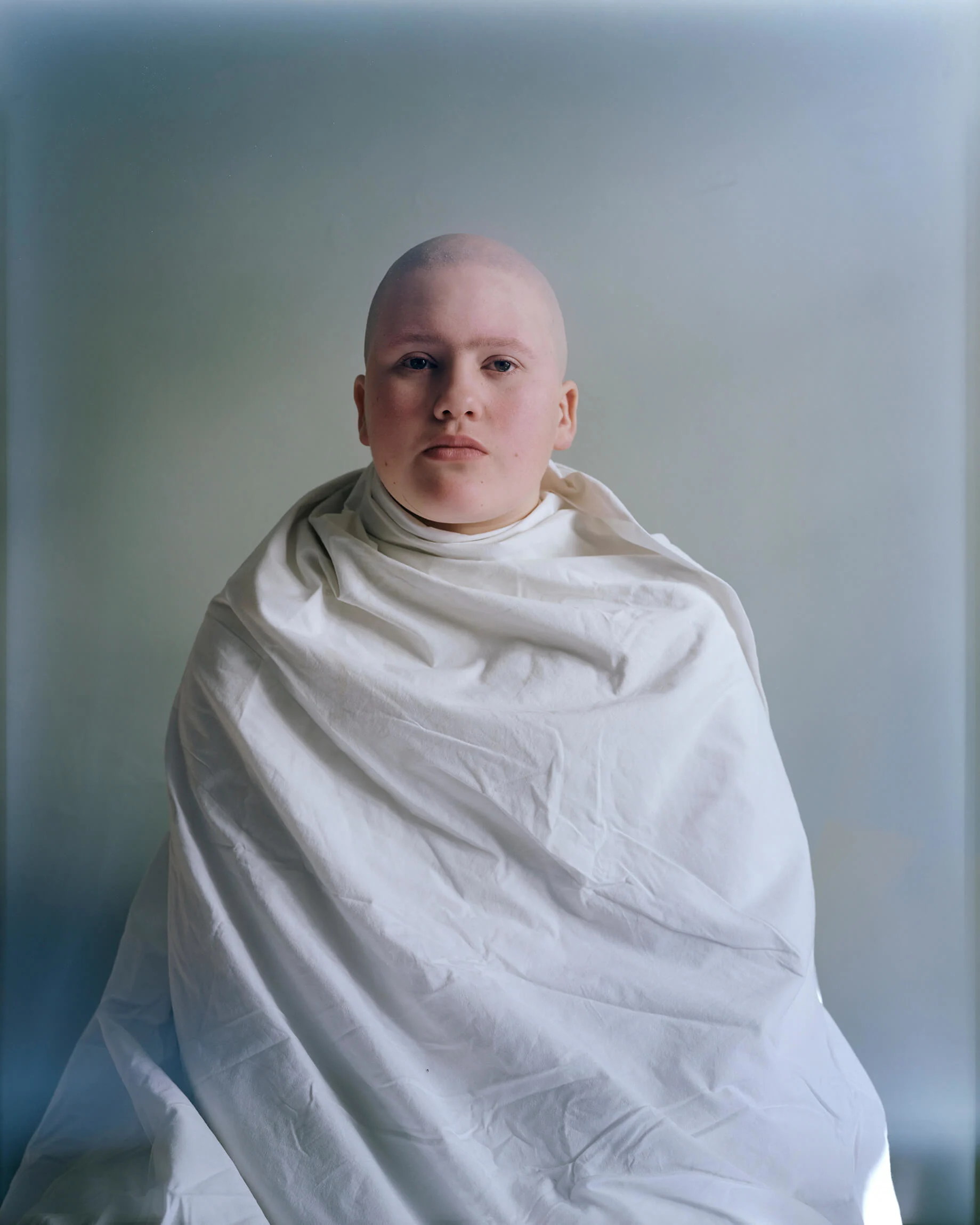

The images she takes with and of Joseph call for a different kind of approach. Although each child has been the focus of their own story, they’re photographed amongst family and friends; tangled and together at home or out in the world. The portraits of Joseph are a departure from this. In them, he sits alone.

“He’s beginning to separate from me,” Siân says. “He needs that to be known in the wider world. He doesn't want my camera around him. He doesn't want his mother around him. He doesn't want to be the focus of his mother. So actually that was the shift: to work only at home with him. His personality demanded that I work in this way with him.”

For example, when Joseph was 13 years old, Siân shot a series of images of him during one sitting, covered by a white sheet and bathed in gentle natural light streaming in through an adjacent window. The shots capture him at various stages of having his brown locks shaved off; the haircut a symbol of the transition he’s making from boy to young adult, with his mother as hairdresser in between takes.

Usually shooting life as it happens, it was new ground for Siân to arrange sittings with her son. “It feels really scary,” she says. “Alice and I had a very clear narrative that I was setting out to communicate. And with Martha the narratives presented themselves as she changed developmentally over the years. In this project with Joseph, all I have is us. And I don't know what that means yet. So there aren't going to be any complex narratives in terms of people coming into the project necessarily. It's just going to be him and me. And that's quite scary, because it feels like a complete kind of deconstruction of everything. And it's about us in our purest form together, and I don't know what that is.”

I had to get out of my comfort zone.

Having photographed Joseph every week for the last two years, recently Siân felt stuck, unsure how to move forward. “I kept repeating these images of Joseph and I felt nothing,” she says. “I work very intuitively and I felt that I’d stopped engaging.”

A visit to an exhibition turned out to be a revelation when she saw a print by the early 20th century German photographer August Sander. She switched from her portable 6x7 camera to a heavy 10x8 large format camera with glass plates that Sander would have used. Siân had always seen this type of camera as quite a macho instrument to be mastered, most often by men, but she’s enjoying using it imperfectly, not knowing what the outcome will produce. “I had to get out of my comfort zone.”

Working in this large format ignited a new lust for the project. “I was kind of sent in another direction,” she says. “A new relationship began, a new kind of love affair began.”

The camera requires Siân to be still and to wait for the moment to present itself to her. “I give myself over to something in this work,” she says. “It feels like all I'm doing is pressing the shutter, and that's it. I'm not running around the countryside and running into nightclubs. I'm just sitting and being present and pressing the shutter.

“My conceptual mind says, well what's that going to do? What's that going to communicate? But then obviously, there is something else going on too. The moment that I press that shutter often tells me something about my own history, something I need to resolve or understand clearly.”

The large format begged for Siân to print the images by hand; a process that has been breathtaking for her. “I’ve literally gone ‘ah!’ when I’ve seen the prints,” she says, “It's like, oh God, you know. And it was always a quiet ambition of mine to see this.”

Considering how working with this camera is different, Siân has come to the conclusion that the camera scrutinizes life in the moment. “That kind of scrutiny or interrogation became really exciting for me, particularly as a psychotherapist. I somehow resonated with that. It just shines a bright light on life, what's in front of you and everything else.

“I’d say working on this format feels slightly overwhelming, because I don't know what we're going to produce or how it's going to work. I just have to have faith that photography, once again, will show me everything I need to know about us, me and Joseph, in this space together.”

Images courtesy of the Michael Hoppen Gallery.

This story is part of Refocus, an initiative to showcase photographic talent from under-represented groups. This time we focus on age, to challenge an industry which too often prizes the newest and the youngest. We gave three grants to three photographers who've seen the industry change over the years, and whose talent is all the better for it. See the whole series here.