When Dutch-Colombian artist Raquel van Haver was in Lagos in 2017, she came across the Area Boys, a group of petty criminals who run the streets. She was desperate to document them. Their reputation preceded them and Raquel’s fixer told her to stay well away. “They are criminals. They will kill you,” he said.

Raquel’s perseverance, though, wore down her fixer’s patience, and a few hours later she was sat among their camp.

Photos by Gert Jan van Rooij.

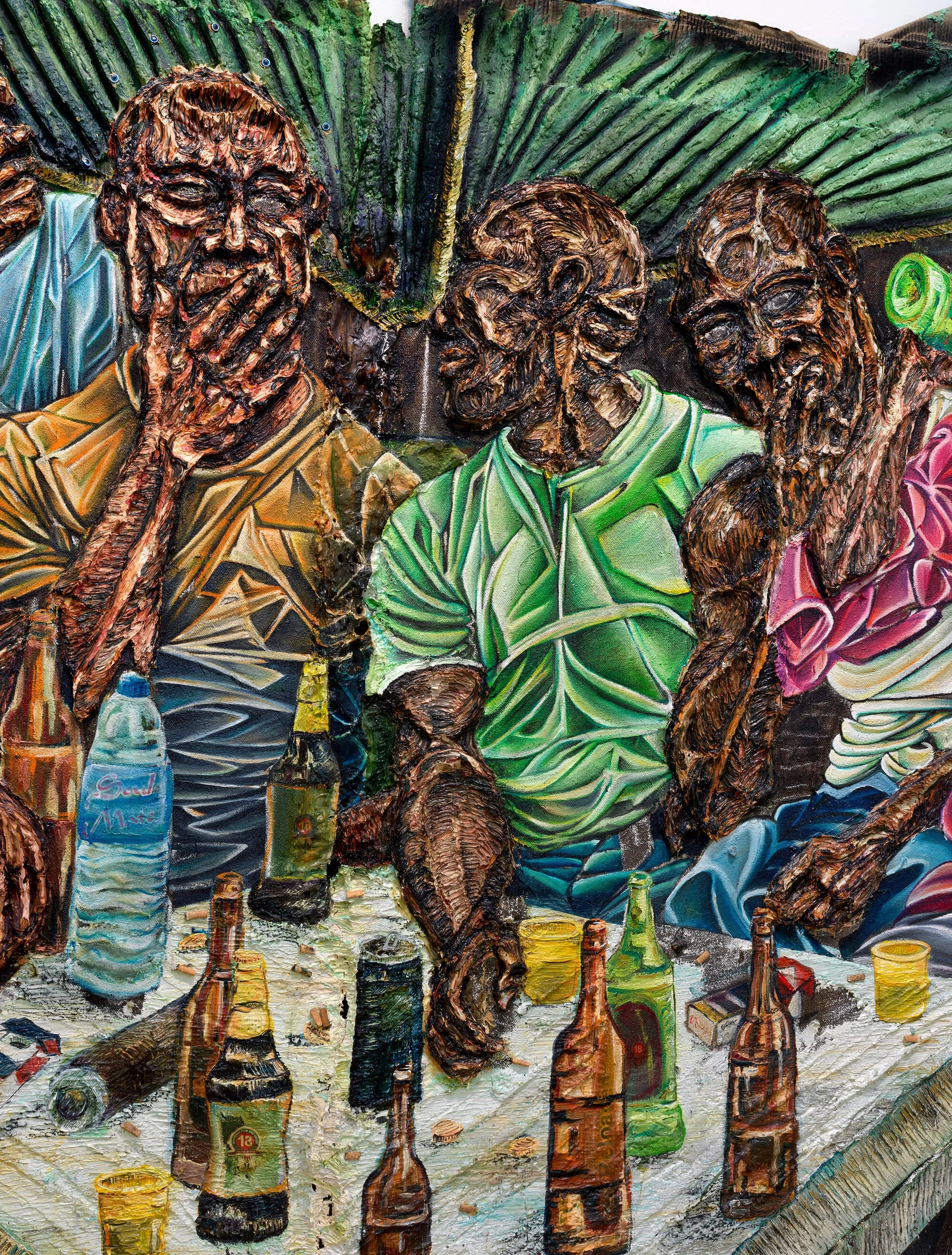

“I became so enchanted by them, because everyone was talking so negatively about them,” she says. The Area Boys had built a compact base, made up of DIY-brick walls with a green tent draped overhead acting as a makeshift roof. A group of men sat around in chairs smoking and drinking, with the television blaring and a fan blowing air around the humid room. People could only enter and sit if their status within the group was deemed worthy enough and so Raquel was met with glaring eyes.

“I felt really feminine at that point. All these guys were big and macho, they were just thinking “why is this girl sitting here?”

Raquel knew the group loved football so she immediately worked to find common ground. She told them she lives next to Ajax’s Johan Cruyff Arena in Amsterdam and they invited her to join them the next day to watch a game. From then on she returned repeatedly to spend time with them. “Everybody was still scared for me. Scared I would be hurt or killed.”

This is emblematic of Raquel’s commitment to immersing herself in a culture before she begins to paint it. She steps into sticky situations in which danger supposedly lurks just around the corner and makes sure to take a good look for herself.

“I had a feeling it was bullshit,” she says, “talking about a group of people like that. Generalizing about them.” Having been in such close proximity to her subjects, Raquel dives into capturing the truth as she sees it.

A lot of people look at my work and see poverty, but it’s actually just practicality.

Raquel takes photographs and uses them as visual cues for her paintings. She doesn’t show specific scenes from any particular place in her works – instead each piece shows a hybrid society made up of references taken from Zimbabwe to Spain, from Lagos to Amsterdam’s multicultural Bijlmermeer, where she lives and works.

“These are all moments of photos I made during 18 years of traveling,” she says. “So I’m just finding the connecting points between the whole diaspora. Things I’ve seen in Europe, in Africa, in the Caribbean.”

These places have found their way in to Raquel’s first solo exhibition, which opened in November 2018 in Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum. The smell of oil fills the air of the exhibition rooms; Raquel created these pieces specifically for this show and some were finished not long before the opening.

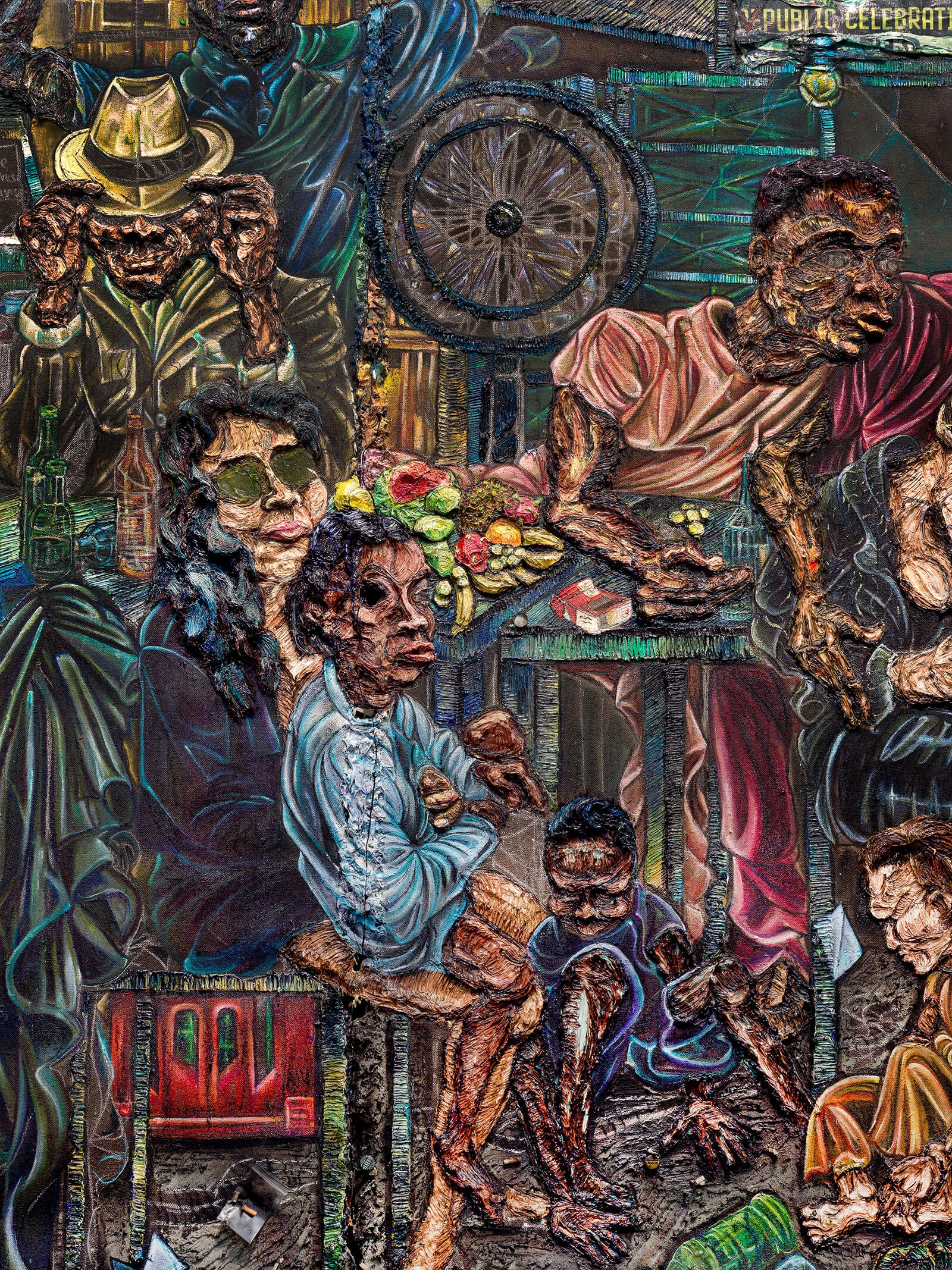

The works leap off the wall with noise and texture. In the huge We Don’t Sleep As We Parade All Through The Night your eye is drawn to every corner. A dog stands chewing scraps to one side. Children sit in the center playing a game on the floor. The 15 adults around the table point, shout, stare and gesture to one another.

It’s a feast of vibrant life, and its vastness – at five by nine meters – means it functions like a life-size window into these cultures.

Raquel uses oil on burlap. She always starts with a sketch as the base of a painting and adds more layers as she goes. Her inventory of materials has gradually grown over time, to the point where she now incorporates hair extensions and other three-dimensional objects into her pieces. It gives great depth to each painting.

For example, in The Eyes Must Be Obeyed, a beer bottle is simply sketched, while the hand holding it is raised and detailed with thick layers of paint. Much of the added texture is focused on the human body in this way, making people the focal point of her paintings.

“The texture of the skin, it needs to be something you want to touch,” Raquel explains. “Something you feel you can hold. You can see the movement in it, and I cannot get that with just a lot of paint.”

Something you don’t understand can be really beautiful and positive – something you can embrace.

Above all else, Raquel wants viewers to look at something, everything, in a different way. “I always want to show the other side, and that has to be real,” she says.

Not everyone enjoys being artistically provoked in this way, but much of that has to do with preconceptions. For example, she finds Western audiences often see chaos and disorder when she depicts people on the street, even though in hotter countries life is often lived outside. "They think of poverty; it’s actually just practicality,” she says.

She finds our collective aversion to disorder strange and unsettling, especially when she looks at The Netherlands from a plane.

"All the fields, the houses, the roads – structure, structure, structure." But life is messier than that, and much more interesting.

“Things get shared and separate lines fuses together and can become so much more than just their individual culture. Europeans influenced Africa, Africa also influenced Latin America and vice versa – there’s always a connection.”

So by painting these scenes from different cultures, Raquel wants to not just normalize our differences, but celebrate them.

“People freak out over something they can’t control,” she says. “But when you bring things to the table and let people discuss these cultures and traditions and learn about them, the hope is that eventually they will change their minds.

"It can be something really beautiful and positive – something you can embrace. It won’t happen with everyone, of course, but I want to show some people they are stuck inside a bubble.”

Words by Alex Kahl.