Quitterie Ithurbide has been teaching sculpture in her Paris studio for years. Among her students, there was one woman with a serious illness who began to gradually lose her sight. Quitterie noted the way the woman’s approach to everything around her changed. “I observed how her fingers began to replace her eyes,” she says.

Years before, as a child, Quitterie spent time with blind children who continued to live like everyone else, but differently. “For example, they cycled, but in tandem, they skied, but accompanied,” she says. “And I understood that it’s crucial for people with disabilities to be included in society and to participate even if it’s in a different manner.” With this in mind, ten years ago she began making sculptures of well-known artworks for the visually impaired.

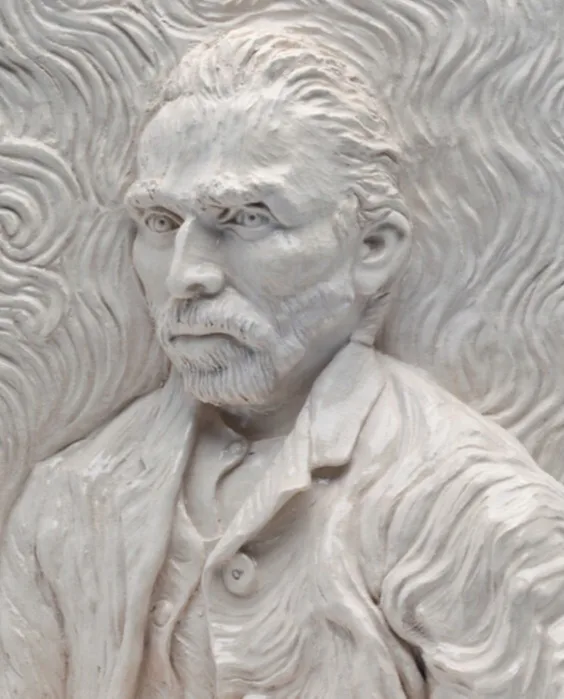

Like 3-D paintings without color, the sculptures are meant to be placed alongside the original artworks in museums. “The aim of this project is to fight the exclusion of blind people from the world of art by allowing them to discover famous paintings through touch”, Quitterie says. “It's like a promenade into the painting.”

Her interest in sculpture began at 18, when she attended the School of Fine Art in Paris, but she soon realized she was more interested in the three dimensional. She left to join a school of art and technology, graduating in stage and set design, and began to paint, sculpt and exhibit. Quitterie was already fixated on recreating things using models, and even set to work sculpting family photos. She completed three years of training in contemporary ceramics in order to bring this latest project to life.

Sometimes the visually impaired have the advantage of touching what we cannot see.

She works in collaboration with a cultural mediator at the Geneva Museum of Art and History, and they discuss which details of each painting are most important to emphasize. This is part of Quitterie’s attempt to depict the scenes as they were intended by the artist, with all the depth and the different layers in the paintings communicated. “I am always trying to make the painting comprehensible for the user without distorting the subject too much. It's very interesting to do. It's a mind game.”

Quitterie goes back and forth between the painting and the model, trying to establish this balance. “I also try to translate the style of the painter, the technique used, pastel, oil, the thickness, the brushstrokes,” she says. Although the sculptures are monochrome, she uses different glazes to translate the light and shadows shown in the original painting – the smoothest glaze for the brightest parts, and the least smooth for the darkest.

Quitterie’s sculptures enable those with visual impairments to better understand the composition of paintings, but there are still some limits. “For instance, the concept of perspective is harder to catch for people born blind,” she says. Indeed, the experience will differ between those who are born blind and those who have lost their sight in later life. “Hence, each new meeting with a viewer tends to bring different feedback.”

Touching the ceramic, unlike the resins or 3D printing, can be sensual.

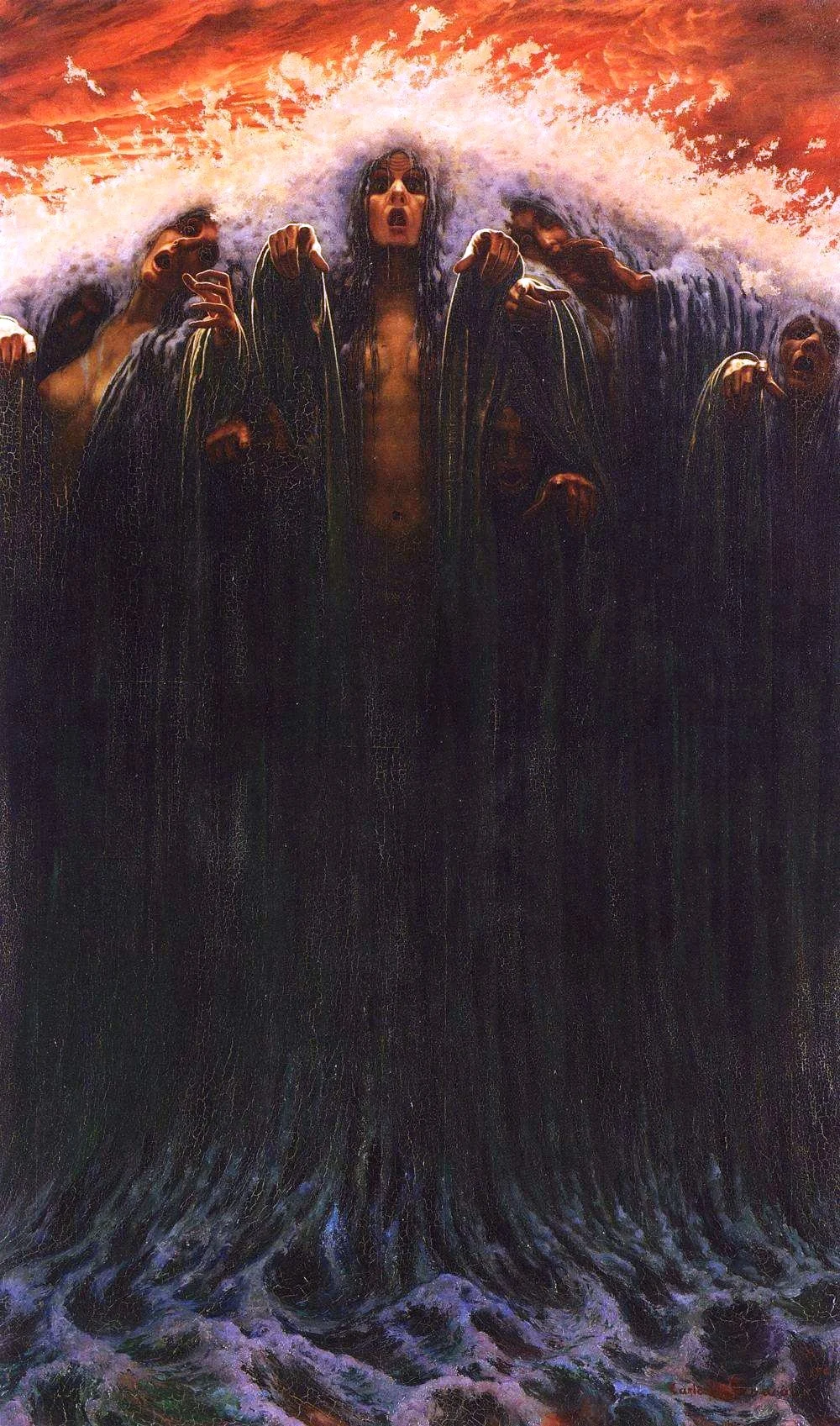

On the other hand, though, there are some aspects Quitterie’s target audience can notice which the sighted may not. Recently, she made a model of Carlos Schwabe’s La Vague. The painting, from 1907, has worn over time, and some parts are filled with shadows. “By brightening the painting on a computer, multiple features I hadn’t seen before appeared on their bodies,” she says. She wondered if she should copy what a sighted person would see in the real, faded version, or try to recreate the original piece closely. “In the end, I integrated those features, so the visually impaired have the advantage of touching what we cannot see.”

Even with a painting that is not so worn, the touchers may still notice something that most viewers do not see. For example, in Munch’s Scream, many never notice the village in the background.

She feels that these models are works of art by themselves, because they offer an emotional experience equivalent to what sighted people feel when viewing a painting. “Touching the ceramic, unlike the resins or 3D printing, can be sensual,” she says.

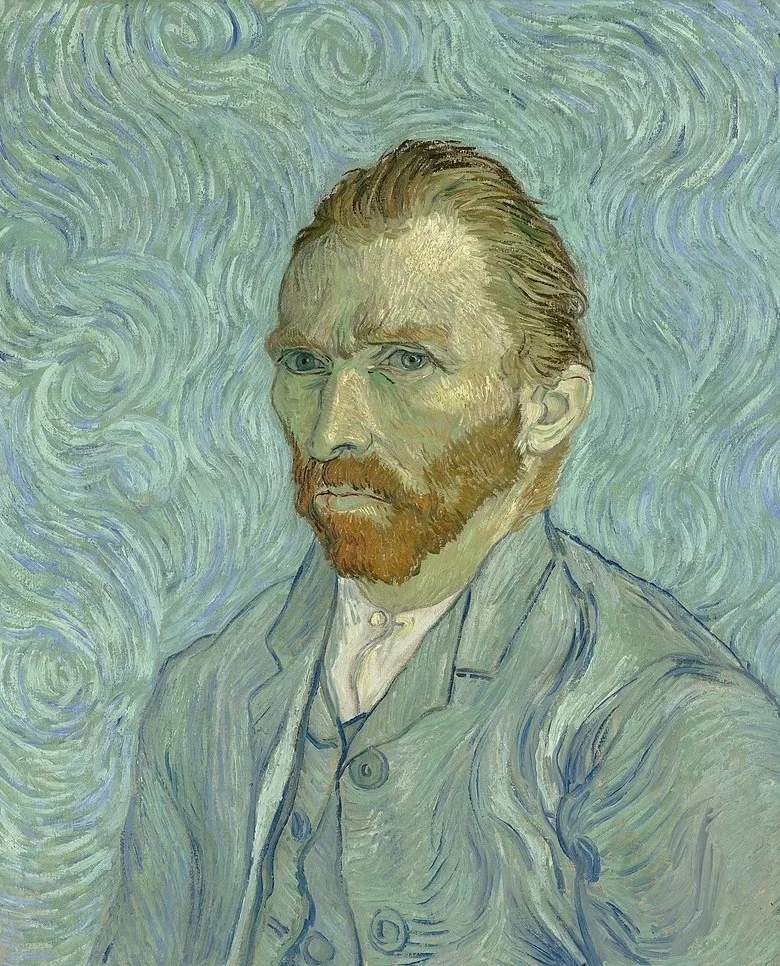

Indeed, towards the end of Quitterie’s video showing the responses to her work, one woman comments, a quiver in her voice, “It really moves me, to be able to touch Van Gogh!”