Are you into puppets? You probably think you’re not. But take a minute, and you realize your relationship with puppets and animatronics goes deeper than you think. Have you ever enjoyed Star Wars? E.T., Alien or Jaws? Thunderbirds or Captain Scarlet? The Muppets, Bagpuss or Sesame Street? The Dark Crystal, The NeverEnding Story, Gremlins, Return To Oz, Labyrinth or Team America? Maybe you are into puppets after all.

Liv Siddall looks at the past, present and future of this intriguing world, and speaks to some of the characters entrenched in it. It's a lot bigger and broader than you might imagine, but no less weird…

In the documentary The Muppet Guys Talking, Frank Oz remembers hanging out with legendary Muppet creator Jim Henson backstage in a TV studio.

They opened a cupboard to find some dirty, grey pipes. Jim Henson shrugged, looked at his watch and said to Frank, “Well, we’ve got some time. Let’s paint ‘em.”

So they collected supplies from their studio, came back and spent three or four hours painting colorful faces onto the pipes in the cupboard. “Then afterwards we just closed the door, did the show, then we packed up and we left,” Frank says. “This is the spirit of The Muppets,” he explains. “This is the spirit of Jim.”

Puppets, creatures and animatronics have been filtered into our lives since we began consuming TV and film. It’s a very pure art form, created by labor-intense craftsmanship and a dedication to a strange combination of acting and artistry. And it was Jim Henson who drove the inescapable puppet renaissance of the 1970s and 80s.

The spike occurred off the back of the pilot episode of Sesame Street which was broadcast in 1969, followed by the launch of The Muppets in 1974, and then – of course – the Star Wars trilogy that blasted onto our screens in 1977, and has continued to smash box office records right up to the present day.

The intense popularity of The Jim Henson Company’s output and the otherworldly success of Star Wars encouraged a raft of new filmmakers to plough time and money into puppet and creature-based movies. In just six years between 1982 and 1988, cinema-goers were treated to The Dark Crystal, The NeverEnding Story, Gremlins, Return To Oz, Legend, Labyrinth and Beetlejuice. What a time to be alive!

But outside of TV and film, puppets have played a key role in our culture way back before these heady decades. For thousands of years now, we haven’t been able to get enough of them. The Ancient Egyptians used marionettes as part of religious ceremonies, while the Greeks used them in their theaters. In different forms and in different places, puppets continued to play a part in popular culture, from the shadow puppets of Japan (bunraku) to the cheap, cheerful and brilliantly violent Punch and Judy shows beloved by the British.

Even new technologies couldn’t displace their popularity. The inventor of television, John Logie Baird, tested his new device using two terrifying “dummy” puppets named Stooky Bill and James (he couldn’t use humans as the lights he needed were too hot). By the time most people had Logie Baird’s TV sets in their homes, they had puppets in their lives too thanks to programs like Watch With Mother.

A few of those puppets, and even some of their original puppeteers, are still around today: in theaters, archives, permanent exhibitions and, in some cases, personal collections. For example, if you peered through a living room window at the end of a noiseless suburban lane in south west London, you’d see Lady Penelope Creighton-Ward. She’s wearing a sequinned evening gown, accessorized with her trademark demure expression.

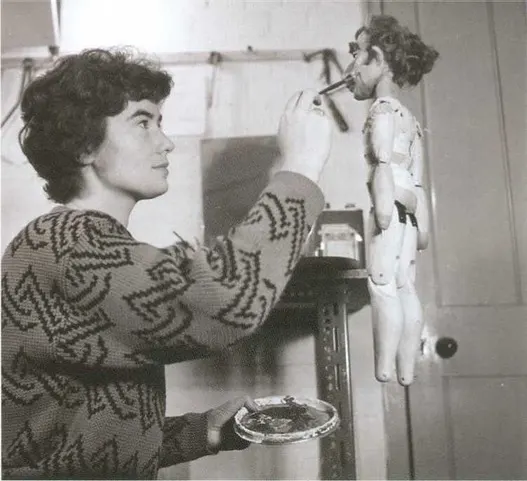

“I haven’t touched her face since the 1960s,” says Mary Turner, looking affectionately at Penelope. “She’s made of fibreglass, her hands are rubber. Her hair is a professionally-made wig. Her eyes move, but her mouth won’t. It’s electronic.”

Lady Penelope is the Lady Penelope of Thunderbirds fame. Mary designed, built and brought her to life in the mid-1960s while working for the show’s famed creators, Gerry and Sylvia Anderson. Since then, Mary – still working at 85 – went on to become one of the most revered people in the puppet scene.

Mary was one of the key players in AP Films (later Century 21) which helped define the popular image of puppets after the Second World War. In that strange grey time in the UK, Mary watched as the adults around her began taking up leisure activities again; hobbies and creative pursuits which had been (understandably) put on the back burner since 1939.

Her mother, an artist, began a puppet-making class at the local college and when Mary was old enough, she recruited Mary and her sisters to be part of a traveling family marionette troupe called The Kerry Puppets. Mary continued to draw and make, despite the effects of rationing. “There just wasn’t much you could do,” she recalls. “Paper was in short supply of course. There was plasticine, so I would make things out of that.”

Mary went on to study sculpture, did a brief stint as a teacher and then joined AP Films through a contact, Christine Glanville. Originally, the company worked out of a ballroom in a Victorian gothic mansion called Islet Park House, before eventually moving to the slightly less romantic Slough Trading Estate. Mary spent time in both locations working on Thunderbirds, Four Feather Falls, Captain Scarlet and Stingray among others.

This estate would later find fame as the home of Wernham Hogg, the fictional paper merchant featured in the original, British (and dare we say better?) version of The Office.

“You’d have a stage for the puppets with the scenery at the back, and over the whole thing you’d have a bridge on which the puppeteers worked,” Mary remembers. “Back then, the puppet wires were about eight feet (250cm) long from where you were down to the stage, but we had a monitor so we could see what we were doing.”

Imagine for a minute how difficult it must be to use your hands to control small puppets from eight feet above, while simultaneously watching a monitor and listening to a script. Interestingly, although Mary was trained in the use of more traditional string marionettes, AP Films used wire to run electricity through the puppets, enabling Mary and her colleagues to control their facial expressions. “The pulse from the tape had to be connected to the puppet at the top and come down the wire,” Mary explains. “There was a solenoid valve inside the heads which worked the mouth.”

After her work with AP, Mary and producer John Read set up their own studio, working on wonderfully-named shows from another era like Mumfie and Cloppa Castle. They also began building meticulously-designed, intricate wooden children’s toys to supplement their entertainment work.

In 1980, Mary and John took part in an event at the British Puppet and Model Theatre Guild in which they displayed the puppets they had made. In the audience, sitting with his father, was a young man called Darryl Worbey.

“Seeing the puppets in the flesh was to have a lasting impact on me,” Darryl wrote in an article for the Guild.

“I was a pretty regular kid, until I caught an episode of Thunderbirds on our black and white TV set,” he recalls years later in his living room. “I was fascinated because whilst what you were watching looked real, you were instinctively aware that it wasn’t. That’s really the first time I had encountered anything like that. I wanted to discover more.”

Fast forward 40 years and Darryl is an award-winning puppet maker who runs his own independent puppet design studio in south London. He’s worked with some of the best-known puppets on some of the most famous movies and TV shows of recent decades. From Basil Brush to the leprechauns on the BBC’s Live & Kicking, Star Wars to classic Muppet remakes of A Christmas Carol and Treasure Island (not to mention Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and The NeverEnding Story 2), Darryl’s career has covered all and he’s still hugely in-demand, working non-stop on TV shows, films and live events.

In his hand-painted, striped living room he’ll show you stacks of photo albums filled with visual evidence of his long, fruitful career. You won’t find photos like these now; documenting anything backstage is forbidden and studios insist workers sign contracts which forbid any spoilers leaking out. But in Darryl’s albums you come face-to-face with what puppetry productions really look like.

Take the scene in The Muppet Christmas Carol for example, when we're first introduced to Ebenezer Scrooge. The streets are suddenly taken over by what seems like hundreds of puppets all singing in unison. Of course, if the camera panned down just a meter or two, it would reveal dozens of fully grown adults in something of a scrum, clambering around each other, eyes locked to mirror-screen monitors while also concentrating on whatever creature sits on their arm.

“For every frog and chicken, there is a puppeteer," Darryl says. "A big part of the technique is making sure no one can see their arms."

“Some puppets are very complex," Darryl explains. “They become finely honed over time and bespoke to the person playing them, almost like an instrument."

As well as performing, Darryl’s job also involved looking after the puppets and repairing any wear and tear that might show up on screen. Messing around with the puppets in any way – let alone sticking one’s hand up someone else’s puppet – is strictly forbidden.

But he also had to look out for the other puppeteers as it can be physically and mentally draining to keep a puppet in shot for hours at a time. “Puppeteers are focusing on giving a performance, getting their hand and puppet to perform to the camera, watching the camera, and maybe even delivering lines of dialogue. It’s a bit like doing three different jobs at once. And rubbing your stomach.”

These days, Darryl is back in the real world after spending two secretive years working on Star Wars – specifically, assisting in the recreation of Yoda for Neal Scanlan’s Creature Effects department.

Some puppets become bespoke to the person playing them, almost like an instrument.

It’s an intense process just to get to the point you can begin building a puppet for a blockbuster franchise. “ is completely made by hand, including the eyeballs,” Darryl explains. There are concept periods and prototypes and meeting after meeting after meeting to sign off the puppet with each relevant person on the production team.

Some jobs though can be less demanding – like the time he was hired to fly to Australia with Basil Brush (the latest iteration of which Darryl created). “He was huge in Australia,” Darryl explains. “There’s a lovely picture of Basil somewhere on Bondi beach. Then a week in Melbourne. Flying first class. Fantastic.”

But as culture changes, puppet-making changes too. It ebbs and flows with trends, demands or the arrival of new technologies. The pace of this change can feel overwhelming, but it’s energizing too.

Like any good craftsman, Darryl’s job relies on skills developed over many years, combined with a knack for embracing and exploring the new. In the puppet and animatronics world, that could be anything from new software to motion capture techniques. Luckily for someone like Darryl – who cheerfully describes his life as “hectic, ever changing, always varied and colorful” – he enjoys the idea that it’s up to each generation to make puppetry its own, just as he did, and Mary before him. “I think that’s really important,” Darryl says. “It’s always reinventing itself.”

Just three years after the 9/11 attacks on New York, Team America: World Police was released in cinemas. Directed and written by South Park creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone, and puppeteered by the Chiodo Brothers, it featured a Broadway actor recruited into a secretive US anti-terrorism unit. It also featured Kim Jong-il – who later turns out to be a cockroach in disguise – a moronic Matt Damon and an extremely graphic puppet sex scene (complete with a memorable 69).

Considering the film was inspired by chaste puppet classics like Thunderbirds and Captain Scarlet, it’s eye-watering how wildly Team America reimagined the art form. And yet, it was part of a wider cultural trend. Long a staple of children’s TV, from the 1990s onwards puppets, Muppets and other creatures began to crop up, or rather were sent up, in naughty, smutty TV, film and theater very much aimed at adults.

There was Avenue Q – a Broadway smash-hit that featured foul-mouthed puppets downloading porn, and songs like Everyone’s A Little Bit Racist. There was Kidding, a Jim Carrey and Michel Gondry series starring Carrey as an ageing, struggling kid’s TV show host. Even The Jim Henson Company got in on the act with The Happytime Murders.

But before this rebirth it looked like puppets might become a thing of the past. Audiences wanted CGI and its mind-boggling special effects. Motion capture brought a sense of reality to films like Lord of the Rings and Avatar, while Pixar pioneered a new type of animated film that had no use for actual models.

Puppetry was going to have to move with the times. As Oscar-winning special effects artist Chris Walas put it, “The future is defined by the innovators. When someone finds a new way to present puppets to the world in the way that Jim Henson did, well, that’s going to be a fun future!”

And so in 2017, in a bid to bring back the spirit of Jim Henson (not literally), Netflix announced a prequel to his puppet and animatronics-filled classic, The Dark Crystal. It would be a ten-part series directed by Louis Leterrier with Jim’s daughter Lisa as executive producer.

The news came as a surprise. Henson had been very open about the challenges of making the incredibly labor-intensive original; challenges made worse when it flopped at the box office.

Little information about the prequel was forthcoming until September 2018 when Louis and Lisa appeared on a panel at New York’s Comic Con. Asked how the new technologies of the past 40 years had changed the story they might tell, Louis suggested it wouldn’t. “Listen, I love CGI,” he said, a smile flickering across his face. “But we’re not using CGI in this one.” The crowd erupted.

Does Netflix ploughing money into a series like this suggest a new era of puppets and animatronics? Perhaps we are acquiring a new taste for them, and we want them darker and weirder than ever before. That appetite seems obvious when looking at the popularity and devout following of Don’t Hug Me I’m Scared (DHMIS).

For anyone not familiar with it, the web series, launched in 2011, features three main characters – Red Guy, Yellow Guy and Duck. The first is a human dressed in a costume, but Yellow Guy and Duck are puppets designed and built in a familiar, friendly, Henson-esque style. Duck has a barely noticeable deranged squint. Yellow Guy is helplessly gormless. Both possess a very subtle, something’s-not-quite-right aspect too.

The characters live in a house made of felt that looks like the set of a children’s TV show and, in each episode, they are led on a journey by a new character (including an overbearing notepad and a slightly evil clock). In every episode the main characters learn something – about time or dreams or love – but things escalate quickly, and comically, into horror.

Creators Becky Sloan and Joe Pelling made DHMIS for the purest reason art can be made – because they felt compelled to. Both graduated art school in the wake of the 2008 financial crash and cast about for what to do; Becky signed on for unemployment benefits to buy herself some creative time. Then she ran into a similarly-lost Joe on a bus, and they decided to make something together.

With the help of friends and collaborators – notably actor and writer Baker Terry – they made a short film in which Muppet-style puppets struggled with dark thoughts and anxieties. “What’s interesting,” Joe says, looking back on the scenes in the first few episodes, “is when you don’t know why it’s unsettling.”

And if tech was challenging the future of puppetry as an art form, it was also opening up amazing new ways to get a stranger sort of content in front of lots of people. That first episode has racked up an astonishing 53 million views (and counting).

Six episodes and seven years later, the duo are now working with Blinkink and pitching a new pilot to TV production companies in the hope of landing a full-length series. They just found out it has been selected for Sundance 2019; clearly puppetry still has a pull.

In order to make this pilot, things had to get serious. Back in 2011 they were filming in whatever spaces they could borrow with whoever they could enlist to help them. “It was just done with no clue,” Joe recalls. “We hired lights and stuff, but we melted the roof and the fire brigade came. They walked in to find us playing with rotten meat on this kid’s show set.”

The new pilot – made with the now-defunct agency Super Deluxe – was a full-blown shoot with dozens of professionals bringing their mad ideas to life. It took nearly a year of intense writing, shooting and puppeteering to make it happen. Sometimes the absurdity of it all got to them.

“There’ll be moments when you’re like, I can’t do this anymore!” Becky says. “You look around at this room of 30 people who haven't slept, and you're all filming something that's so dumb and stupid.”

One of those they called on to help was Lesa Gillespie, an actress, puppeteer and motion capture artist from Belfast. “I love kids TV, but I’ve been doing it for nearly 15 years and I wanted something a bit meatier and a bit darker,” Lesa says. “So when my agent phoned me about Don’t Hug Me, I watched it and thought, this is right up my street.”

Nobody cares if it’s you. It’s the character that matters.

In the mid-2000s, Lesa was up for a puppeteering role and the person auditioning her was the legendary Martin “Marty” P. Robinson, AKA Snuffleupagus in Sesame Street. You’ll see Marty in any of the show’s behind-the-scenes photos; he’s got a huge Brian May-style mane of curls and a gigantic grin. He met his now-wife while working on the show and they got married on the set, the ceremony heckled by Oscar the Grouch.

Meeting Marty at the group interview changed the course of Lesa’s career. “This crazy American fella comes in and said, ‘Put all of those puppets away because I’m going to teach you something that you’ve never been taught before’,’” Lesa remembers.

“So the 30 of us went in, stood before a mirror and we were all given little eyeballs on the back of our hands. Then he just taught us the basics of lip sync. You had to learn how to do it all with your thumb.”

“The more you push up through your shoulder or arm, the more clearance you give your puppet, so the more freedom you’ve got to be able to do stuff with the character,” she explains. “It keeps your head out of the frame. The thing is, it’s really painful.”

This level of professionalism wowed Becky and Joe, but Lesa too was impressed with DHMIS, and particularly the lack of ego on set, compared to other projects she’d worked on.

“You get to that point where you’re just about to do something that’s really interesting, and the main puppeteer will come in and go, ‘Oh I’ll do that.’ It’s because they want that moment in front of the camera, even though nobody knows who it is!” Lesa says, clearly exasperated.

“That level of ego I find really interesting,” she continues. “Nobody cares if it’s you, and nobody cares if it’s somebody else. It’s the character that matters. No kid on the planet looks at Elmo and goes, oh that’s Kevin or that’s Ryan. They go, that’s Elmo!”

Back in the 1970s, growing up in North Yorkshire, Peter Brooke wasn’t your average teenager. In his spare time he’d labor over masks, models, puppets and plaster casts. “I made ape suits, I made a troll head, I learnt how to make a plaster mould and pour liquid latex in to make a halloween-style slip mask,” Peter recalls. “You’d have to find household objects and materials and figure out if you could make it do something.”

Peter’s teachers were less enthusiastic about his creative career plans.“I’d say, ‘I want to do special creature effects!’ And they’d say, ‘What are you talking about’?” They suggested he become a fireman or a doctor.

But a few years later Peter graduated from Manchester Polytechnic and swiftly began working in Jim Henson’s Creature Shop. He’s still there, 30 years later, in the role of creative supervisor working on projects such as the new Dark Crystal Netflix series. For someone like Peter, who grew up tinkering with puppets and mainlining Henson films, he’s basically won at life.

His studio is a room full of workbenches, extraction booths, boxes of fur, fabrics, odd sculptures, moulds and containers full of eyes and noses. Next door there are lathes, drills, 3D printers, cutting machines and tools with which you can create custom builds for animatronics.

“It’s art school, times ten,” says Peter. ‘We really make an effort to make a nice creative atmosphere, because oftentimes there’ll be 30 people here who are tasked with having to come up with something that’s never been done before. You need to make sure the environment is conducive to that.”

Peter’s journey – from odd, glue-fingered teenage boy to one of the creative leads of the most influential puppet studios in the world – comes down, he believes, to education.

Every Monday at his school, the whole morning was dedicated to art. His teachers pushed him to try new techniques – mould-making using bronze powder, fibreglass resin and a whole load of other stuff which wouldn’t be allowed these days.

“We did ceramics and glazing; we went out on field trips photographing things; I was part of an orchestra and a jazz band,” he recalls. “It saddens me to think that kids nowadays don’t have those opportunities. Even if you don’t bother doing art ever again in your life, there are aspects which – to a developing mind – are really important.”

Around the world the stats make for grim reading. Things like art, design and music get squeezed out as the so-called STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and maths) take center stage. In higher education, creative courses too are under pressure as student debts skyrocket and people look for degrees that will help them pay off their loans as quickly as possible.

There is now only one place left in the UK where you can study puppetry, the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama. The university, tucked away on a leafy avenue by London’s Swiss Cottage station, offers a course called Puppetry: Design and Performance and is headed up by Cariad Astles, a stalwart of the UK puppet scene.

The puppet studios at Central are very much like the environment at Creature Shop that Peter Brookes described. There are boxes of foam and fabric and plastic bags of jointed limbs. There’s a store cupboard in which you can find old puppet detritus, such as the head of polar bear Iorek Byrnison from His Dark Materials (donated by the National Theatre after the show in 2004).

Cariad runs through some notable projects by students past and present. One created a giant, outdoor marionette of Don Quixote, another made puppets which reflected her dating history. One made a touring show about the Bubonic Plague. “They want to be able to make a living from making art,” Cariad explains. But that’s not easy and the number of students on the course has dropped in recent years.

Maybe that’s not as doom and gloom as it sounds. Over in Los Angeles, Isaiah Saxon – director of Encyclopaedia Pictura and founder of kids’ learning site DIY – believes there’s no better time to be a young person interested in puppetry.

He thinks that thanks to online communities and especially YouTube, the “more formal institutional support or lack thereof” is not a problem. “I think that puppeteering and stop motion and things like that should remain an amateurs’ art form,” he says. “It will always be something for people who get obsessed with that illusion of life that can be created, and just do it with their own resources.”

Isaiah, a big champion of the DIY maker movement, is currently working on his first feature film, The Legend of Ochi. It’s a live action fantasy adventure which will be shot in Romania in the summer of 2019. He says it’s about, “a young girl who’s into black metal and hates people but loves animals, who saves a young mysterious primate baby from a fur trap. She then realizes she can talk to it through a whistled language and decides she must find out where it’s from, and return it.”

The film is going to be live action, with puppets and animatronics for the creatures. “Pretty immediately I was like, if this is a CGI creature, this movie’s gonna suck,” Isaiah explains.

It’s going to be a long and difficult project. Isaiah, his main collaborator – London-based animatronics prodigy John Nolan – and the rest of the team will spend 18 months just on the preparation.

“This isn’t how most people approach films,” he shrugs. “But I think for something that needs to be incredibly composed and visually ambitious, that involves animatronics and effects and all this stuff, it requires this level of planning.” He is hell-bent on his animatronics being believable.

“You should never feel like, oh this is just a cute puppet. I want people to be like, how did they train this weird primate baby to act like this?” To create more fluidity, Isiah’s team will rod puppeteer the bodies and remotely control the faces. If they succeed, they can then create massively memorable moments between the creatures and the human actors.

“One of my goals is to have the scene where this girl discovers this creature to be the first time she’s ever seen it, and to be rolling on her face when she sees it,” he says. “There are certain things that are ephemeral and impossible to redo, and that’s one of them.”

Life’s like a movie, write your own ending. Keep believing, keep pretending.

But to pull this off you need to surround yourself with people who appreciate the artform of puppetry and animatronics. “A lot of film crews aren’t used to the absurd level of patience and perfectionism required to pull off the illusion of life with these things,” Isaiah says. “I’ve definitely experienced wanting to do a 50th take when the entire crew is like, why haven’t we moved on? This person is insane.”

This insanity reflects Isaiah’s passion to make a movie that steps as far away from CGI as possible. He’d like The Legend of Ochi to inspire young people to make creature effects movies, just as he was inspired by films like E.T. and Jaws when he was growing up.

He wants to show young audiences that a career in special effects might not be as fulfilling as they may be led to believe. “You end up with a lot of people who aren’t actually creatively empowered, who are becoming cogs in a machine,” he says. “The fact that puppets and practical effects are a sort of marginal art form, to me, makes it a form that attracts independent thinkers who don’t want to work in a big company and who can do things in a DIY way. The future is right where it should be.”

You can’t help feeling excited when you speak to Isaiah. He‘s a real believer – in the power of creativity, in the importance of allowing children freedom of expression, and in the level of dedication needed to make something truly spectacular.

It’s the same qualities that animated Jim Henson, the man who changed everything. “You can never have another Jim Henson,” Isaiah admits. “He found something that was so inherent to the medium – this design language, this style of puppeteering and this spirit.”

Culture may change, technology may change, education may change, but that spirit endures. Puppeteering is like any creative industry, thriving off imagination, extraordinary craftsmanship, collaboration and the drive to keep exploring. As Kermit sings in Rainbow Connection, a song written by Jim Henson himself, “Life's like a movie, write your own ending. Keep believing, keep pretending.”