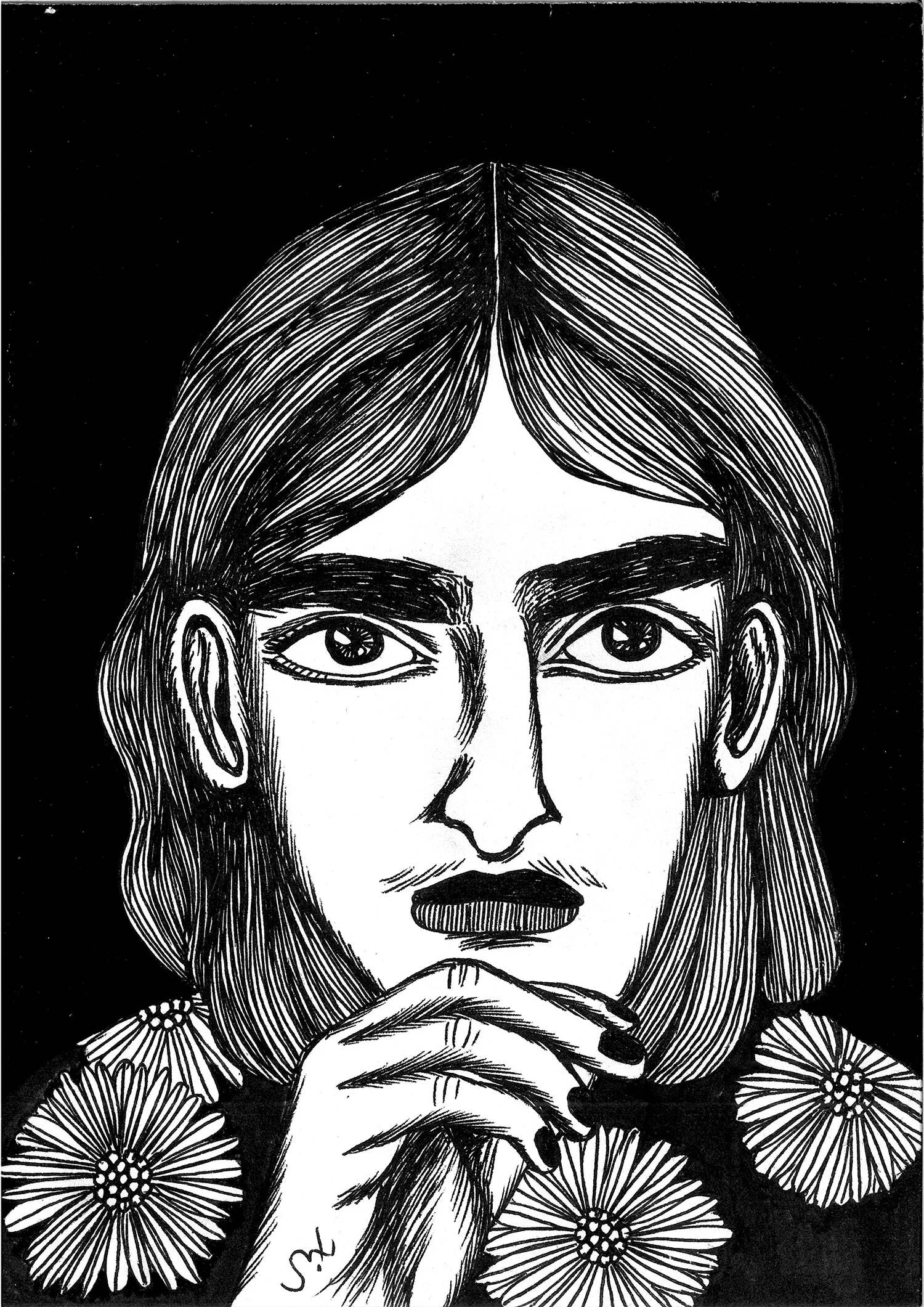

Artist and activist Moshtari Hilal works exclusively in black ink pens. “I like to think of my black lines as a homage to black-haired bodies,” she says.

Thick brows accentuate the dark eyes of the women in her works and prominent noses rise between them. Black hair lines their upper lips and grows down their forearms below their sleeves. These black markings stand out in sharp relief against the white of the paper she draws on, as deliberate as her desire to create a space where people who look like her are visible and celebrated.

Born in Kabul, Moshtari and her family moved to Germany when she was two, so she grew up immersed in a Eurocentric beauty ideal regurgitated on billboards, in magazines, on TV screens and in museums.

When the body positive movement started to gain ground and diversity became a buzzword, Moshtari was disillusioned to watch how poorly it lived up to its promises.

“Somehow those responsible managed to cast people who still looked very similar; the closest to what a caucasian face was expected to look like,” she says. “So you would have campaigns about diversity in beauty, and the ‘ethnic’ tokens would still have a European button nose — not too wide, too big or too flat.”

I felt like an alien — absent in most of the visual content that was produced.

It wasn’t just noses. Faces were never too round or too long. Skin was smooth and hairless, “as if body hair was a total aberration in nature,” Moshtari says. “This narrow image of facial beauty deeply affected me as a young girl.

“I felt like an alien — absent in most of the visual content that was produced. Specific faces would be either invisible or singled out for negative character traits.”

Moshtari’s response is #embracetheface, a portrait series and social media movement encouraging people to appreciate their own facial features. On the internet she found her audience in the Afghan, Muslim, South Asian and Middle Eastern diaspora.

“Embrace The Face is about understanding that we internalized years and years of colonial propaganda about what is supposed to be beautiful and good,” she says. “Our self-hate became someone else's profit. Just look at the market in the Global South and its population: we are being offered highly toxic bleaching products, both for facial hair and skin. Companies like Fair & Lovely are selling the most in South Asia and Africa. There is also a huge market for rhinoplasty targeting ‘ethnic noses’, and these are only two examples of many.”

Using her pens as a tool for change, Moshtari draws a variety of faces that she doesn’t see in the arts and mainstream media. She started with herself though – one of her first art projects was a series of self-portraits, inspired by Frida Kahlo’s radical approach to the art form.

“My early work is mainly learning about myself – as an artist and object of artistic practice,” she says.

“To what extent is my visual imagination restricted by the beauty standards that flood all media every day? How can I resist, or even reclaim, my sense of aesthetic?”

In her latest work, which she describes as semi-autobiographical, Moshtari is inspired by members of her family. She draws crowded scenes of different generations huddled together on a couch or around a birthday cake for a photograph. The intricate patterns on the tapestries and scatter cushions she draws, and the traditional dress of some of the subjects, mix cultural heritage with recent history. “Most of my research is based on family photographs from the early 1990s and 2000s, during the civil war and our collective escape as refugees from Kabul,” she explains.

I learned how art made it possible to bond with people.

While there’s power in making sure all kinds of faces are seen, Moshtari’s work is also concerned with making voices heard. Frustrated by the lack of refugee perspectives in the debates about immigration that have played out in recent years, in 2016 Moshtari staged a political public art performance in Hamburg called #Refugeetoo. On a busy street, she gradually unrolled 11 metres of black paper and with a white marker, wrote out ideas she’d gathered from former and current refugees — the people at the heart of the matter.

Encouraged by the rich visual history of her country of birth, Moshtari has recently started AVAH, short for Afghan Visual Arts & History, together with Shogofa Wafa, Yasmeen Gailani and Muheb Esmat. The collective of artists, art historians and curators are working on an online index of Afghan artists past and present and publishing a zine.

Her own artistic awakening happened in Kabul, during the summer of 2012. She joined a group of artists to paint murals around the city. “During this time I learned how art made it possible to bond with people, and how I felt so much more visible and understood through my work,” she says.

But when she got back to Germany she was disturbed by the apolitical attitude of local art students. She studied social sciences and taught herself art on the side.

This gave her the freedom to develop her own visual language which mixes the directness of graphic novels, the rebellious, DIY spirit of zines and the urgency of cheaply printed pamphlets. It’s this energy, more than anything, that drives her messages home.