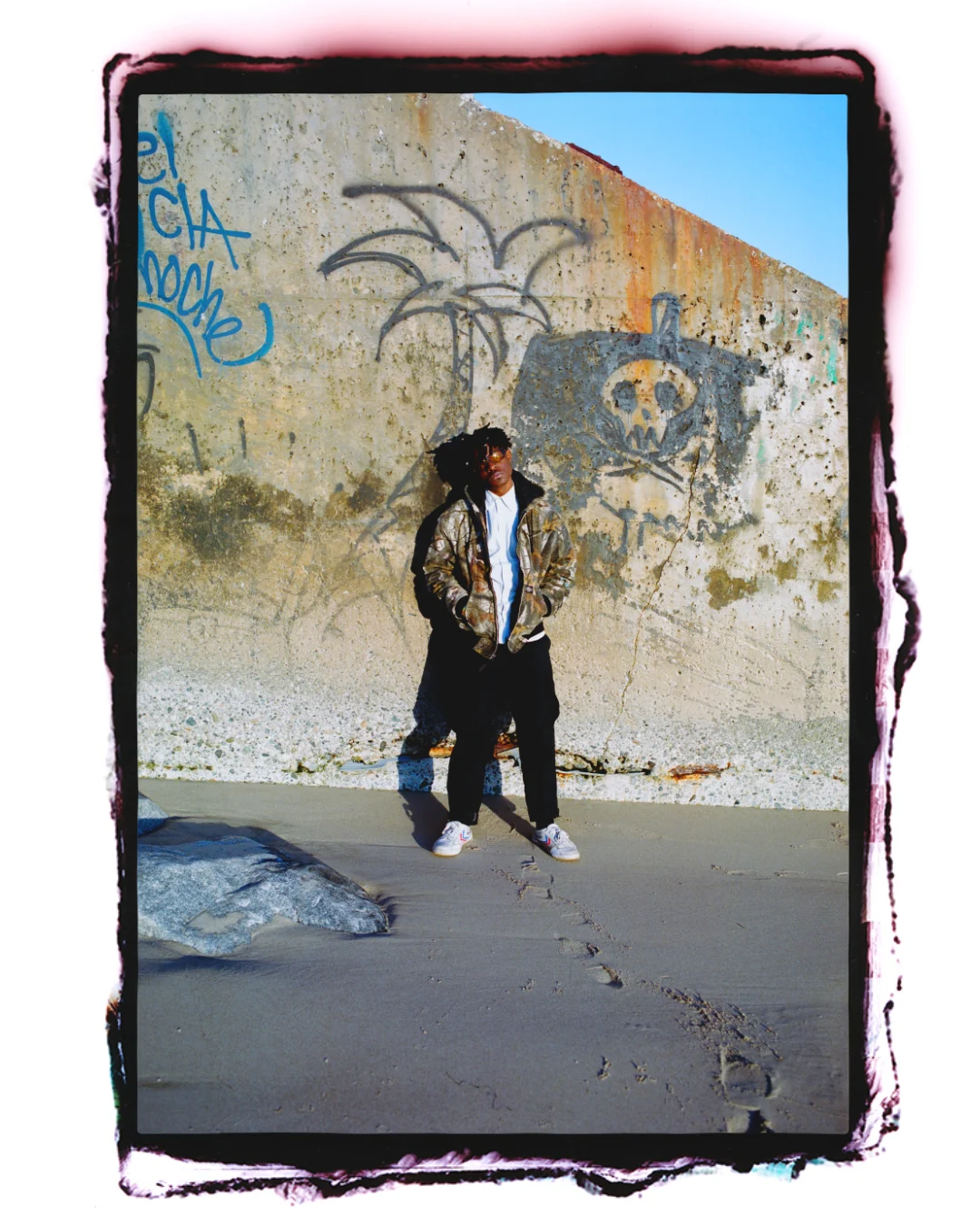

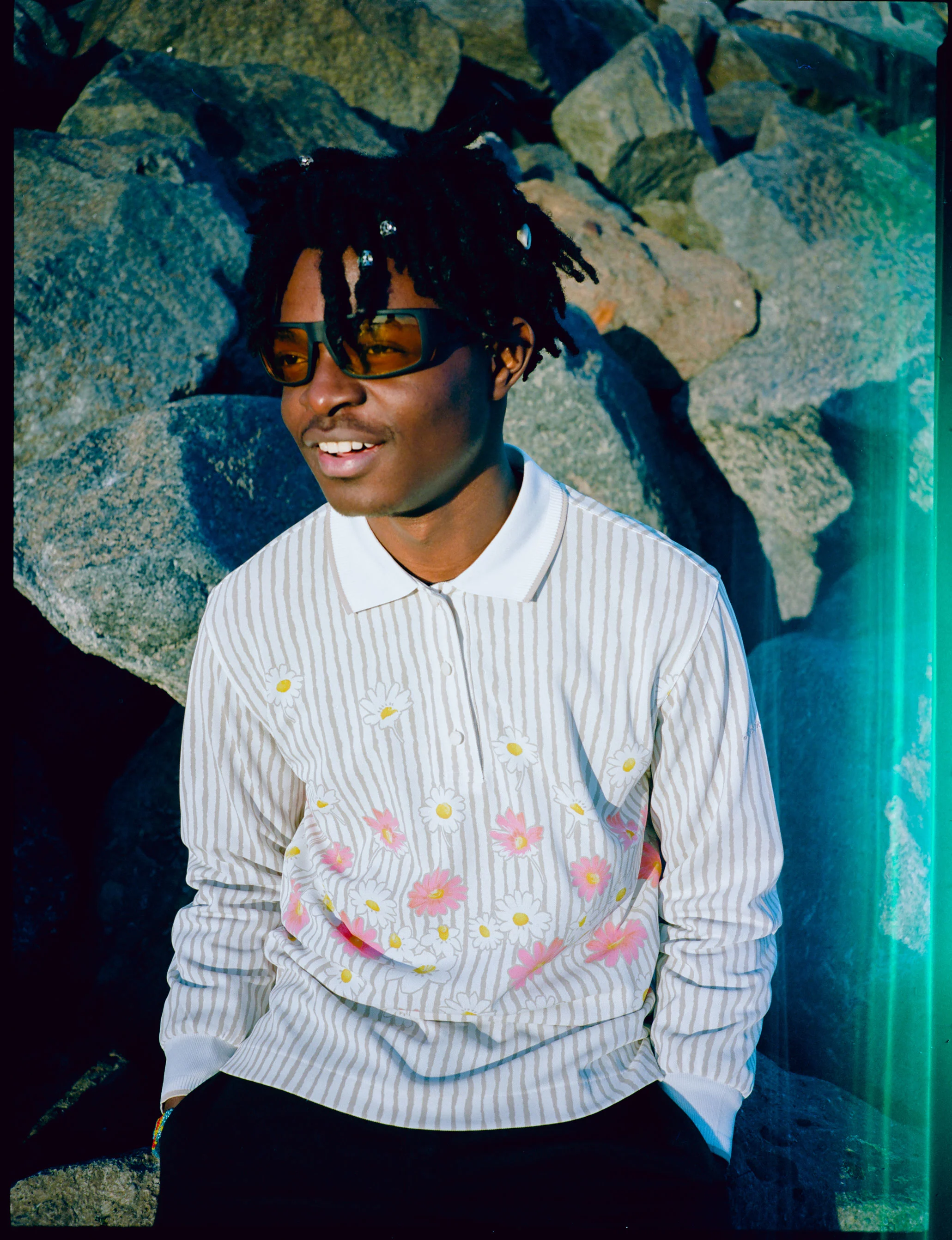

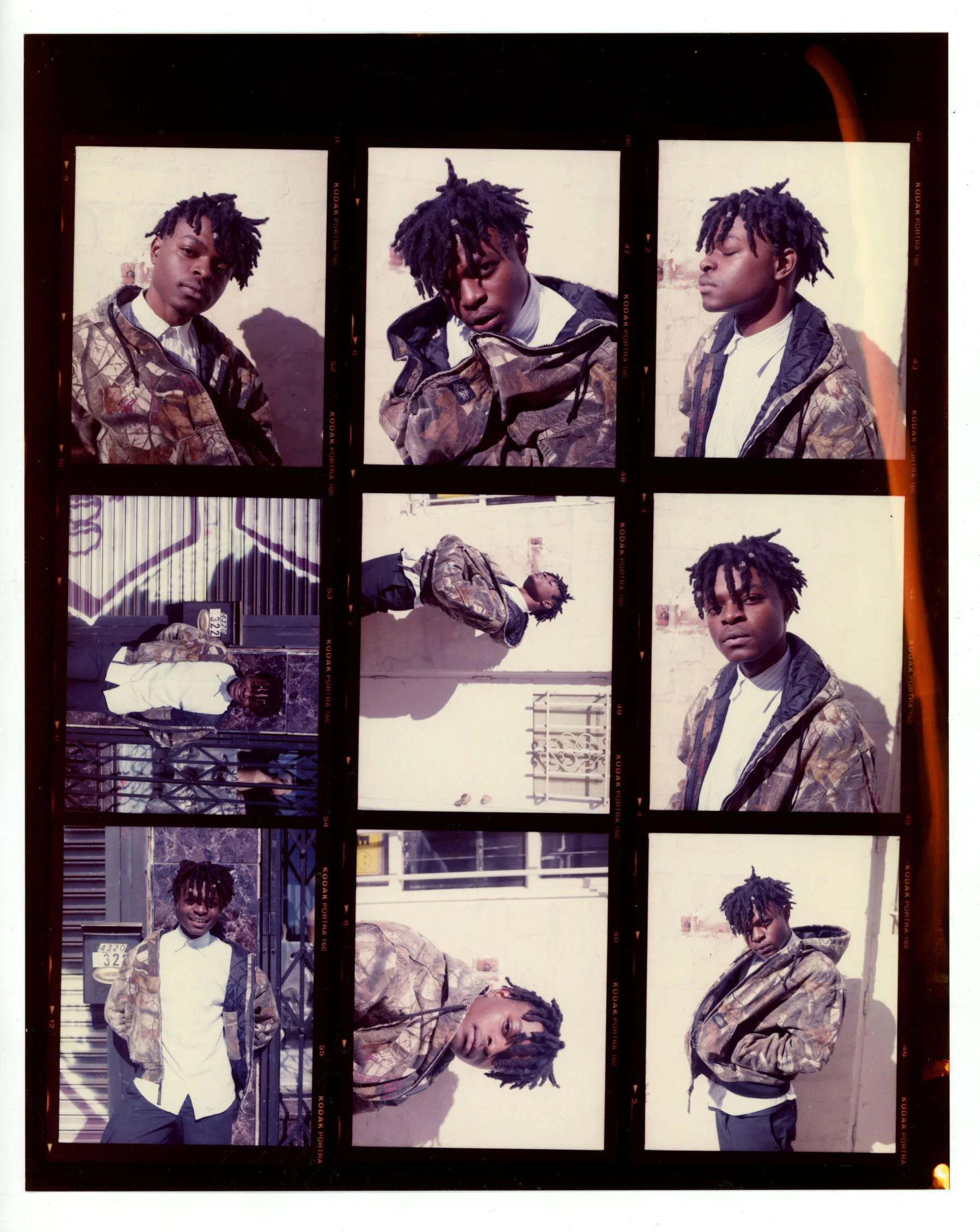

From a young age, singer-songwriter Bobby Kabeya – who performs under the name Miloe – was encouraged by his parents to follow his artistic passions wherever they led. And now, at 20, he’s followed them to a burgeoning career making dreamy bedroom pop, subtly infused with the spirit of the Congolese rumba he grew up with. Ahead of the release of his debut EP, “Gaps,” Kabeya opens up to Tara Joshi about his creative upbringing, his musical evolution and creating songs that “can bring you to a place outside of time.”

Bobby Kabeya, aka Miloe, has a poster of the Grammy-winning pianist and producer Robert Glasper stuck to a wall of his bedroom in Minneapolis. In the striking image, Glasper stares down the camera lens, toothpick perched from his lips, as a tattoo gun marks the words “FUCK YO FEELINGS” onto his bicep in heavy black strokes. “I found that poster on the inside of his vinyl,” Miloe explains. “I like the energy that it’s embodying.”

When we speak over a video call, the 20-year-old singer-songwriter exudes quite a different energy. Calm and affable, he drifts from small talk about the frigid Minnesota weather and the supplements he’s taking, to deeper ruminations on his work – dreamy bedroom pop that he’s put out under the name Miloe since 2018.

At this point, we’re a few months away from the release of his third EP, “Gaps.” The six-song collection exudes an expansive warmth through sweet pop melodies and tender lyrics looking at relationships, exploration and displacement. It’s a record about music as release and creativity as a “flow state” from anxiety, he says, and songs “that can bring you to a place outside of time.”

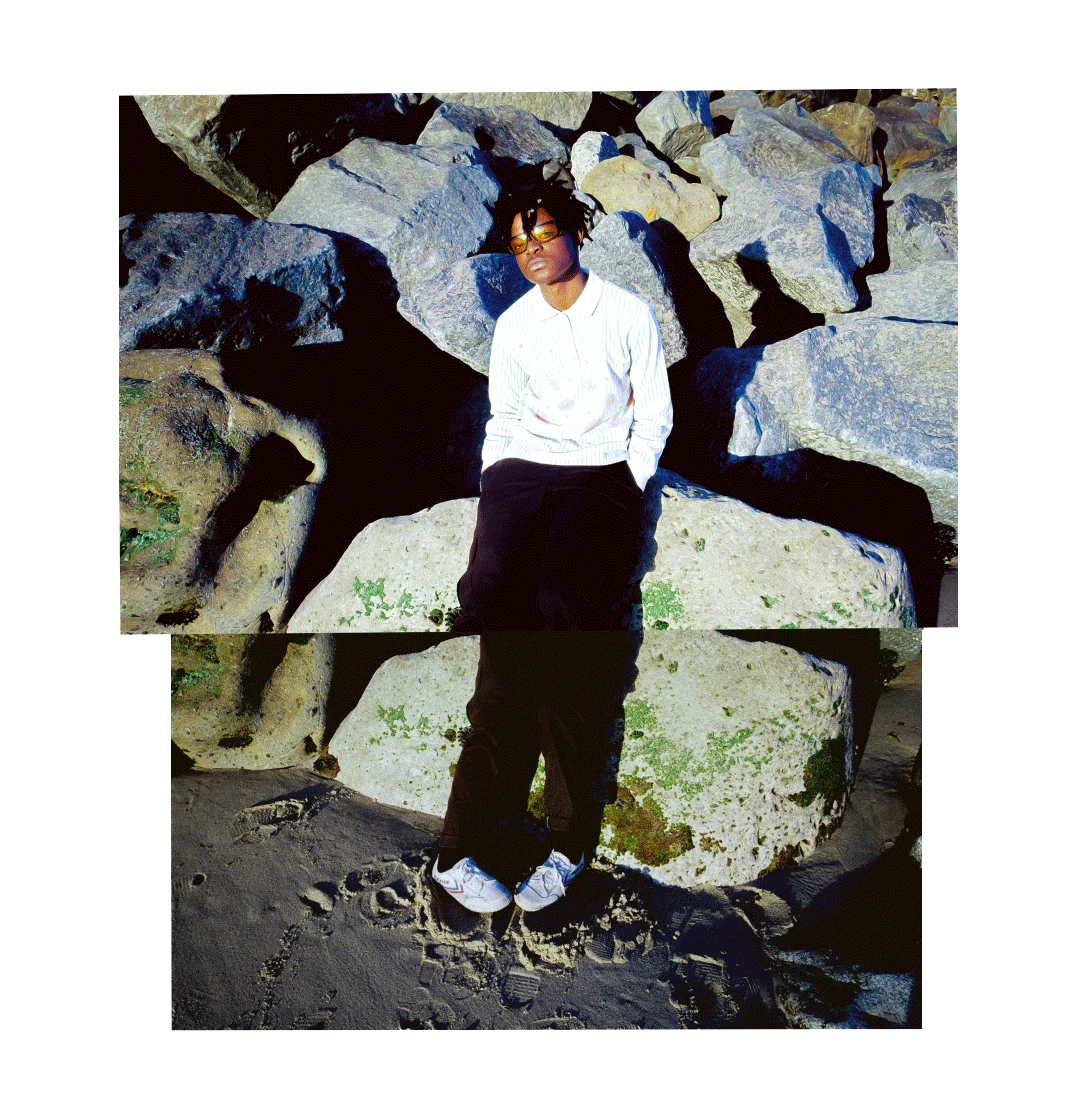

“For ‘Gaps,’ I’ve been really inspired by photos from the Hubble [Space Telescope] – these vintage photos of deep space,” he says. “The way the stars have this cool lens flare, the textures are really nice. In my head, it matches the textures of the songs.”

Music is so important to Congolese culture because it’s where we really get to express ourselves.

Miloe credits his devotion to music in part to his upbringing in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). “Music is so important to Congolese culture because it’s where we really get to express ourselves,” he says. Around the country, Congolese rumba music – a form of dance music inspired by son cubano, with bright, bluesy guitars and big bands – is a particular source of pride (“We have a distinct style that we brought to Africa and the world”), and with this project, Miloe has dug deep to express these roots. You can hear nods to it in everything from the intricate rhythms and swoony guitars to the dense vocal harmonies.

Miloe was born in Mbuji-Mayi, the country’s second biggest city, and later moved to the capital, Kinshasa, with his family. But his time in the DCR didn’t last long: when Miloe was five, his journalist father, who had been reporting on government corruption, fled to Minneapolis to escape the threat of persecution and, three years later, Miloe, his mother and his two siblings moved over to join him. “[The prospect of] the move was a source of hope in the harder times when I missed my dad, or when the climate in the country felt more unstable,” he recalls.

The reality of the move was more complicated than he’d expected. “I'm fortunate to have highly educated parents – they spent a lot of years in school back home, and achieved a lot – but I had to watch them completely restart from scratch in America. Capitalism is unforgiving in the ways it makes people overwork with little return. One of my biggest motivators is to provide them with a better standard of living, just like they did for me.”

Still, contrary to much of the mythology surrounding first- and second-generation immigrants, Miloe’s parents encouraged him and his siblings to pursue creative fields. They themselves met in a choir, and some of Miloe’s earliest memories are of watching his mother perform. They even named him “Bobby” after Bob Marley.

Miloe had already been studying piano for two years before he arrived in the States, and when he did, he was surprised to find that his father had taught himself GarageBand and recorded a couple of demos. “This very much made my brothers and I want to make stuff with him at home,” Miloe says. “We formed a sibling boy band called the K Boyz and recorded a song about waiting for the school bus in the cold.”

In the States, Miloe began playing drums in his church choir, and later played in high school pop-rock bands, inspired by the likes of Cage The Elephant, Imagine Dragons and Alt-J. After graduating, he enrolled in Minneapolis Community and Technical College, and played raucous gigs with various bands in people’s basements, before striking out on his own. In 2018, an initial plan to make a jazz EP turned into a SoundCloud page of original lo-fi bedroom pop and the occasional cover. He chose the stage name Miloe as a subtle reference to the 2011 Coldplay album Mylo Xyloto, which Miloe credits with widening his interest beyond the Top 40. (“‘Whatcha Say’ by Jason Derulo was one of my favourite songs when we moved.”)

Live shows are where the Miloe project has felt most tangible to me. They’re instrumental to how I write and how I continue to progress.

Soon after, he graduated from playing house parties to proper Minneapolis venues, with a few friends playing backup. “Live shows are where the Miloe project has felt most tangible to me,” he says. “They’re instrumental to how I write and how I continue to progress.”

The last couple of years have been surreal for the artist. He signed his first deal with record label Loma Vista in 2020, and toured across the US the following year as a support act for Beach Bunny. While his stature grew, his family was never far behind: in 2020, his parents even directed the fuzzy, colorful video for his summery bop “Winona.”

I want to express myself in a way that’s most true to me.

And now, he’s excited to get “Gaps” out into the world. “I’m really proud of it,” he says, smiling. “I feel like I pushed myself on it. They sound good quality, not – bedroom quality.” In pushing himself on this record, Miloe hopes “Gaps” represents his life and its roots, but also his own artistic intuition – something his father always encouraged him to trust in. “I want to express myself in a way that's most true to me,” he says. “Hopefully others can see themselves in that work.”