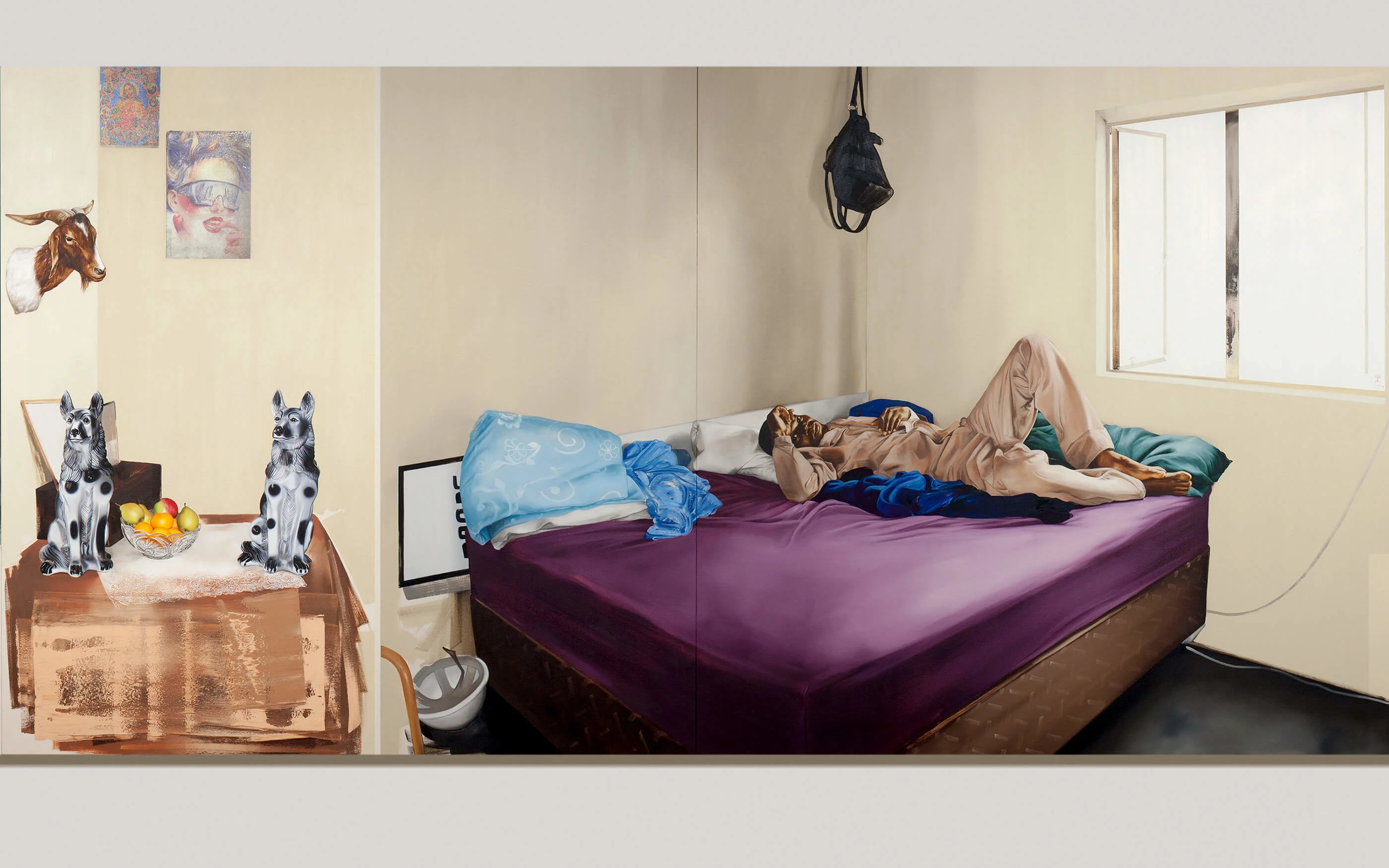

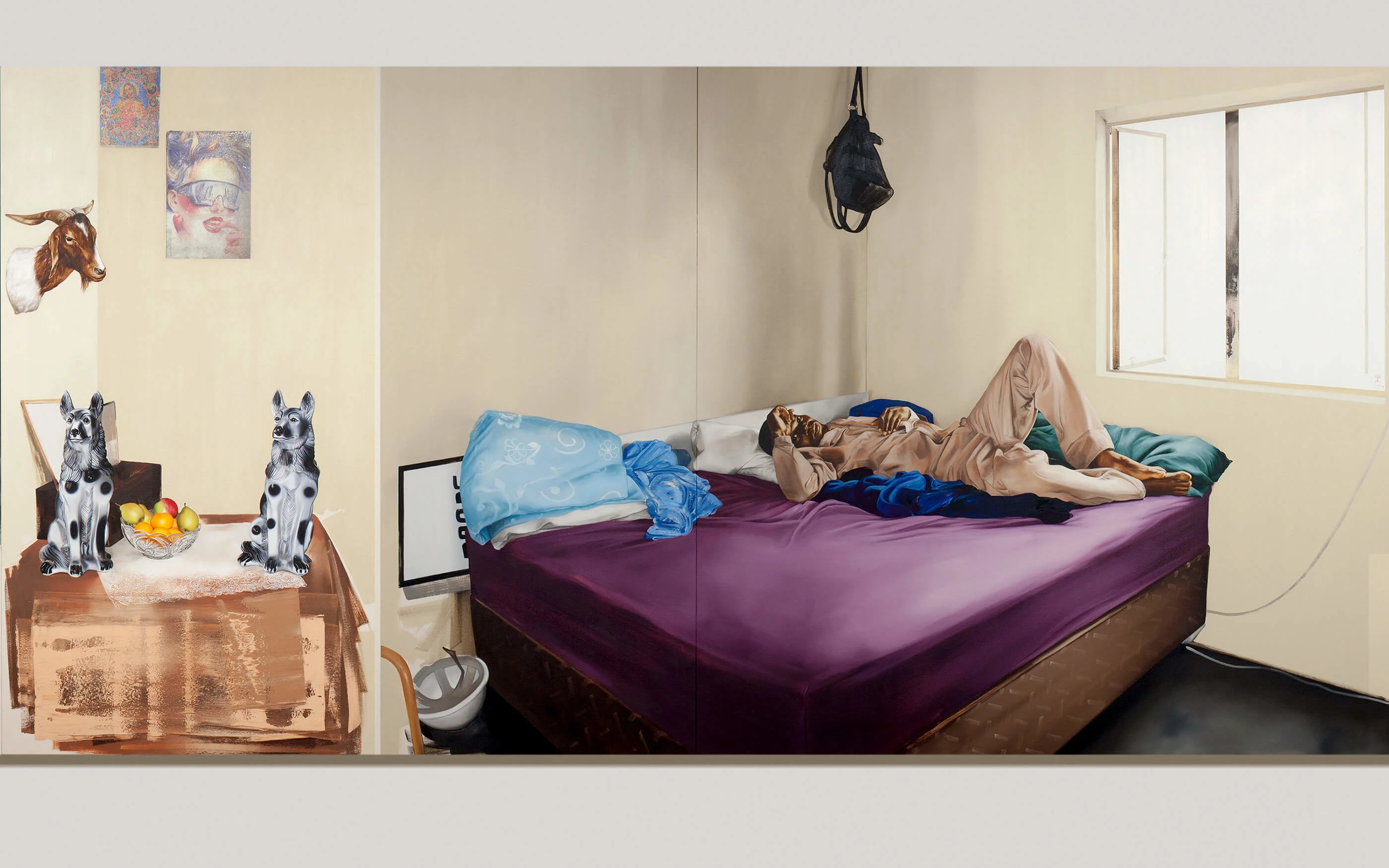

In one of the scenes from Motswana painter Meleko Mokgosi’s exhibition Bread, Butter, and Power a man lies on his back on an unmade bed in a sparse bedroom. His dusty backpack hangs from the wall and a hat lies on the floor. Across the gallery hangs an image of high school students grouped together for a photo in their maroon and white-striped ties and blazers.

The scenes are normal sights in southern Africa, but by choosing to reproduce them in paint, Meleko suggests there’s more to consider. He raises questions about past and present politics, and the systems of power at play in everyday life. Where does western education fit in a post-colonial southern Africa? Who benefits from the labor of black mine workers?

Based in New York where he teaches at NYU, Meleko travels home to his family in Botswana at least once a year. He paints from the photos he takes on these trips. But while his reference material renders his style realistic, he doesn’t want to label it as realism.

“My argument has always been that we can never trust any interpretation of reality,” he says. So instead, he gives the viewer room to question their position in the system they live in, without taking it for granted.

Good ideas take time to arrive, but slow and boring is in many ways a privilege.

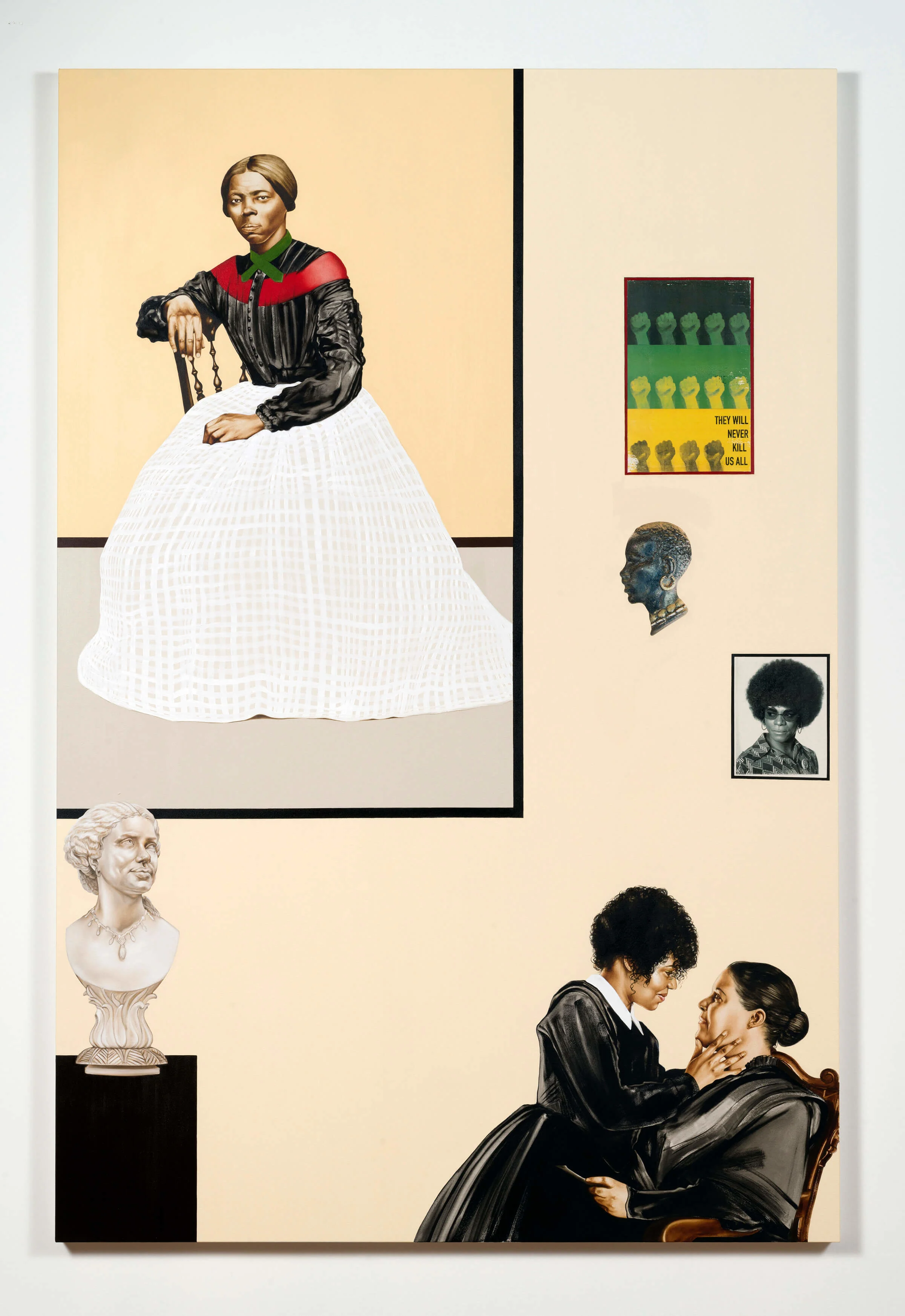

In his long-term project Democratic Intuition for example, started in 2014 and released in eight chapters, he looks at how democracy shapes the daily experience of the black subject.

In one of the chapters, Acts of Resistance, a young woman lounges on a couch in front of a TV showing freedom fighter Winnie Madikizela-Mandela raising her fist in apartheid-era South Africa.

In another, a young man in blue workers' trousers sits below the famous 1955 image of glamorous South African singer Miriam Makeba, shot for the cover of Drum magazine (an important publication known for changing the way black people were represented in society.)

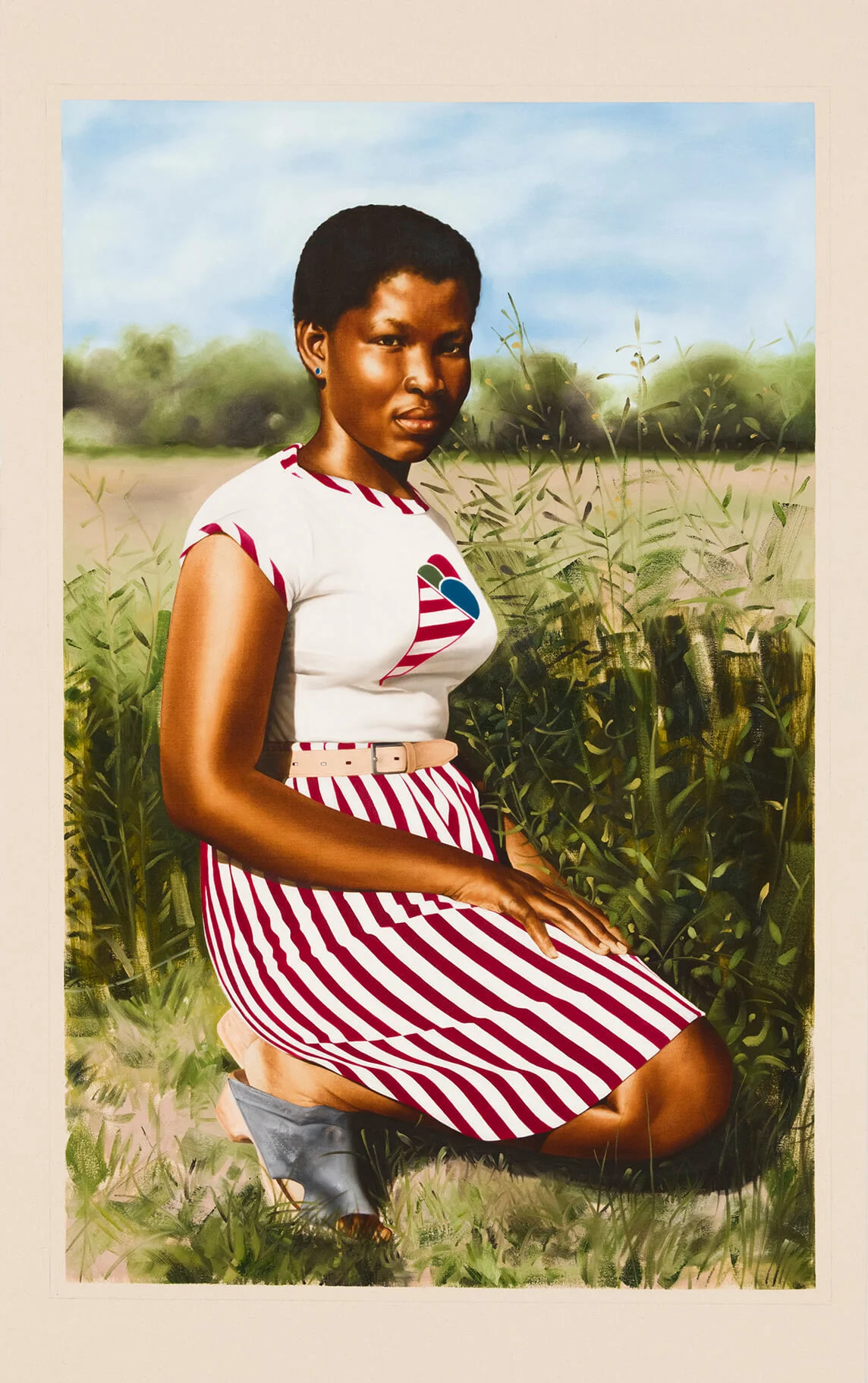

Women play an important role in Meleko’s paintings, as they do in his Tswana culture. In his chapter Bread, Butter, and Power which was exhibited at the Fowler Museum at UCLA in 2017, he addresses gendered divisions of labor in southern Africa and how these manifest in daily life.

The installation looks at intersecting oppressions and the history, meaning and practice of African feminism in a southern African context. Raised largely by his mother and grandmother, Meleko wanted to explore different generations' experiences in the workforce.

“Some paintings show children and market stands, alluding to the work women do in unregulated informal markets to provide for their families. In other interior scenes, it’s the absence of women that speaks to the hurdles they are yet to overcome. And two bleach paintings covered in Setswana text, my mother tongue, retell women’s stories that have been passed down orally for generations.”

The ways in which light reflects and refracts off the painted surface produces different and unexpected visual experiences.

Over the years, he’s developed an innovative way of painting luminous black skin. Instead of using white gesso as a base, he uses a clear priming medium to retain the beige color of his cotton duck canvas. This helps him capture the texture and color of black skin tones.

He also uses an untraditional combination of materials to make up his hues: burnt umber, raw umber, burnt sienna and raw sienna which he paints on with a specific glazing technique. “The ways in which light reflects and refracts off the painted surface produces different and unexpected visual experiences,” he says.

Standing in front of one of Meleko’s paintings you are met with a life-size subject, “to create a one-to-one correlation between the viewer and subject in the painting.”

Artistically, this also draws a comparison between his work and traditional European art. “I have always thought of myself as a historical painter that tries to create a counter-narrative about the history, legacy and effects of European imperialism, now capitalism,” he says.

To Meleko, historical painting from Europe was more than just a particular style; it was used to communicate the “western moral” to shape the ideals of early modern society. “Those ideals included knowledge, reason and honor, but also bellicosity, the sovereignty of elites, white supremacy and the dominance of men,” he says.

By painting black African subjects using the tropes and tools affiliated with the European genre, Meleko hopes to create a sustained dialogue around aesthetics and cultural production in southern Africa. “Which is crucial,” he says, “because the art historical framework seems to only be tendentiously and periodically interested in the black African body.”

I am able to construct a space that allows the viewer to interact with the work without feeling overwhelmed.

His paintings consist of eight, 12 or 16 panels installed in sequences like film strips in dialogue with one another. He first writes the titles of the chapters and then storyboards them with line drawings arranged in order. He leaves parts of his paintings untouched, comparing the open spaces to the pauses so important to storytelling in film.

“This way, I am able to construct a space that allows the viewer to interact with the work without feeling overwhelmed by ten large paintings installed edge to edge,” he says. “In addition to allowing space for reflection and interaction, I try to use negative space to show my investment in an economy of materials and language. That is, to be strategic about painterly language.”

This strategic approach takes time though. Between his art practice, his teaching work and his love of in-depth reserach, his work can take years.

“I think good ideas take long to arrive,” he says. “So there is no point rushing and also risking a reactionary proposition. However, I do understand this approach is somewhat slow and boring; but boring is in many ways a privilege.”