As the world has progressed at a wild pace, many things in our lives have changed, but the way we process death and loss doesn’t seem to be one of them. Polish artist Marta Klara has noticed this, and her solution is a virtual reality memorial experience, “ini,” which brings the concept of a funeral hurtling into the digital sphere. She tells writer Joe Zadeh how she took influence from the traditions and rituals of the past and repurposed them into a forward-thinking approach of the future.

Death, despite being commonly referred to as such, is not a taboo. Our lives are constantly littered with confrontations with death. The daily coverage of war, disease and disaster ensures that the death of humans, animals, plants and ecosystems constantly permeates our attention. The most popular TV shows, documentaries and podcasts are those that concern themselves with the most brutal and mysterious of deaths. Against this backdrop, the idea that death is a taboo in 21st century western culture is ridiculous. If anything, we’re due a breather from daily death.

And yet in some ways it is a taboo. Death on a personal level—our own death, or that of those we hold closest—is a far more terrifying and existential thought to wrestle with, and one we’re inclined to ignore until it explodes into our lives and smacks us in the face. “When I worked in a funeral home in the UK, everyone wanted everything over in like 15 minutes,” says Marta Klara, a Polish artist and filmmaker, and an artist-in-residence at Sarabande Foundation.

When I worked in a funeral home, everyone wanted everything over in 15 minutes.

Klara’s practice explores the intersection between art and technology, and experiments with ways in which the line between the digital realm and the physical world can be blurred. Her latest work, “ini,” is described as a “digital farewell concierge”; or, as Klara more casually calls it: “digital mummification.”

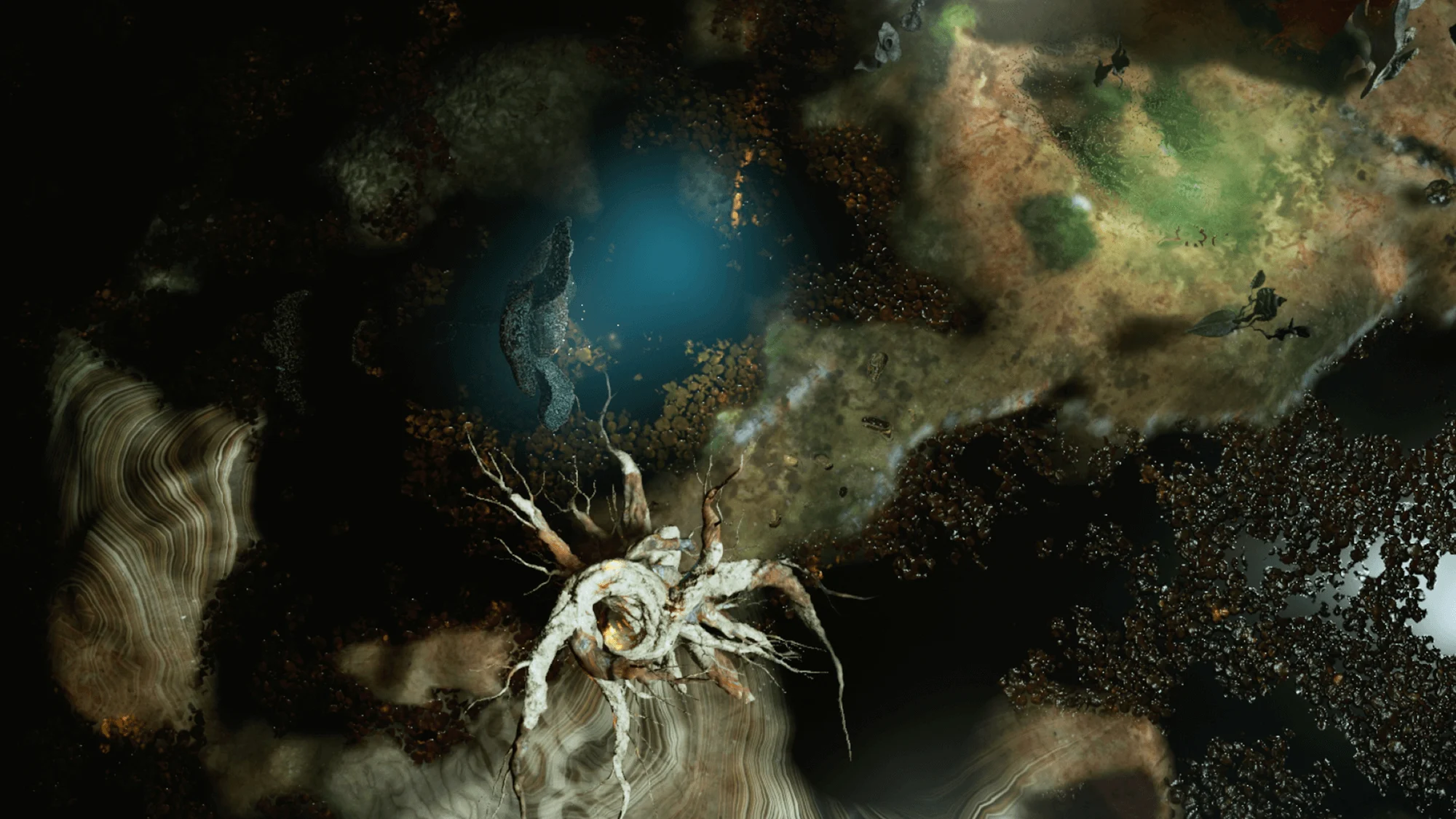

The premise is simple: a bereaved party (or someone who wishes to plan for their own death) comes to “ini,” in the same way someone would contact a funeral home. Klara would then conduct a series of in-depth conversations about the experiences, memories and details that relate to their loss—“I’d try to understand your stories and get in your shoes,” she says. From this, she creates a visual response. The crux of the response is a bespoke virtual reality environment (built using Unreal Engine), which serves as a celebration of the deceased and a place for the bereaved to explore, reflect and process.

Imagine an otherworldly VR experience in which the landscape, sounds, and colors—as well as physical aspects like smells and sensations—are all meticulously curated based on the stories and memories of the deceased. “Since before the Ancient Egyptians, whose conception of death inspired them to build the pyramids, humans have long sought to ‘create’ around death,” reads the deck that explains “ini.” “A digital afterlife aims to provide individuals and communities with the closure they seek and need, in order to forge a path forward.”

With a background in film and fashion, Klara was well-placed to design the visual aesthetic and narrative of the experience, but also collaborated with sound artists, VR specialists, animators, lighting experts, 3D modelers and even fragrance scientists to craft the environment. But the research of grief and bereavement required the more hands-on approach of getting a job in a funeral home. For a year, Klara transported and dressed bodies, built coffins and directed the funerals themselves.

“It was a slightly more progressive funeral home…” she says. “But the taboo—the feeling that you need to get over it quickly and not spend too much time grieving—was still there. I felt like families wanted closure as soon as possible, rather than getting too far into celebration or personal elements. But I think if there is anything or anyone to blame, it's the culture. It doesn't prepare individuals for that time. [Death] happens out of nowhere, and then we have no tools to deal with it.”

A digital afterlife aims to provide individuals and communities with the closure they need.

“ini” isn’t just aimed at revolutionizing funerals, but our entire approach to processing loss and moving forward in our lives. “It could be used for your final funeral, your death,” says Klara, “but I feel like it would almost be better if it was for a micro death: any shadow loss in your life, like a divorce, a pet, a job, or saying goodbye to your old digital avatar. Anything you would like to bury and move on from into an exciting new chapter. I think it's better to start with these micro deaths, so we can slowly change the mentality and discourse around loss… I want to warm people up to this idea.”

To create a prototype, Klara crafted a digital farewell for her own micro death: the burial of a digital avatar she had used as a child. It was a way to bury a part of her past, she explained, while also “acknowledging the rising value of the digital world.” The experience was displayed earlier this year at Baker McKenzie's flagship event “A Bling New World,” and included in the exhibition “Uhrformen” at the Sarabande Foundation.

Rituals, wrote the philosopher Byung Hul Chan, are symbolic acts that “represent, and pass on, the values and orders on which a community is based.” Rituals often took hundreds if not thousands of years to form, and their meaning and symbolism was rooted in ways of being. Many of them now feel alien and irrelevant to life in a hyper rational and hyper accelerated culture. Symbolic acts once imbued with meaning now feel empty and meaningless, and the biggest moments of our lives can often slip by, unprocessed and uncelebrated. It no longer feels quite so sacred when a child becomes an adult, a home is built or the last full moon of the summer rises. Perhaps the radical experimentation of “ini” is what is required to reinvigorate some of our old traditions with modern meanings.

“I think there was so much richness and meaning in the way rituals used to bind communities,” says Klara, “but just being nostalgic for that is not the way. I don’t think people should gather around a fire in a cave and pretend it isn’t the 21st century. I want to develop something that gives meaning, but is exciting and approachable for a modern audience. I believe in ideas that contain something from the past that is relevant to the here and now, but also look to the future.”