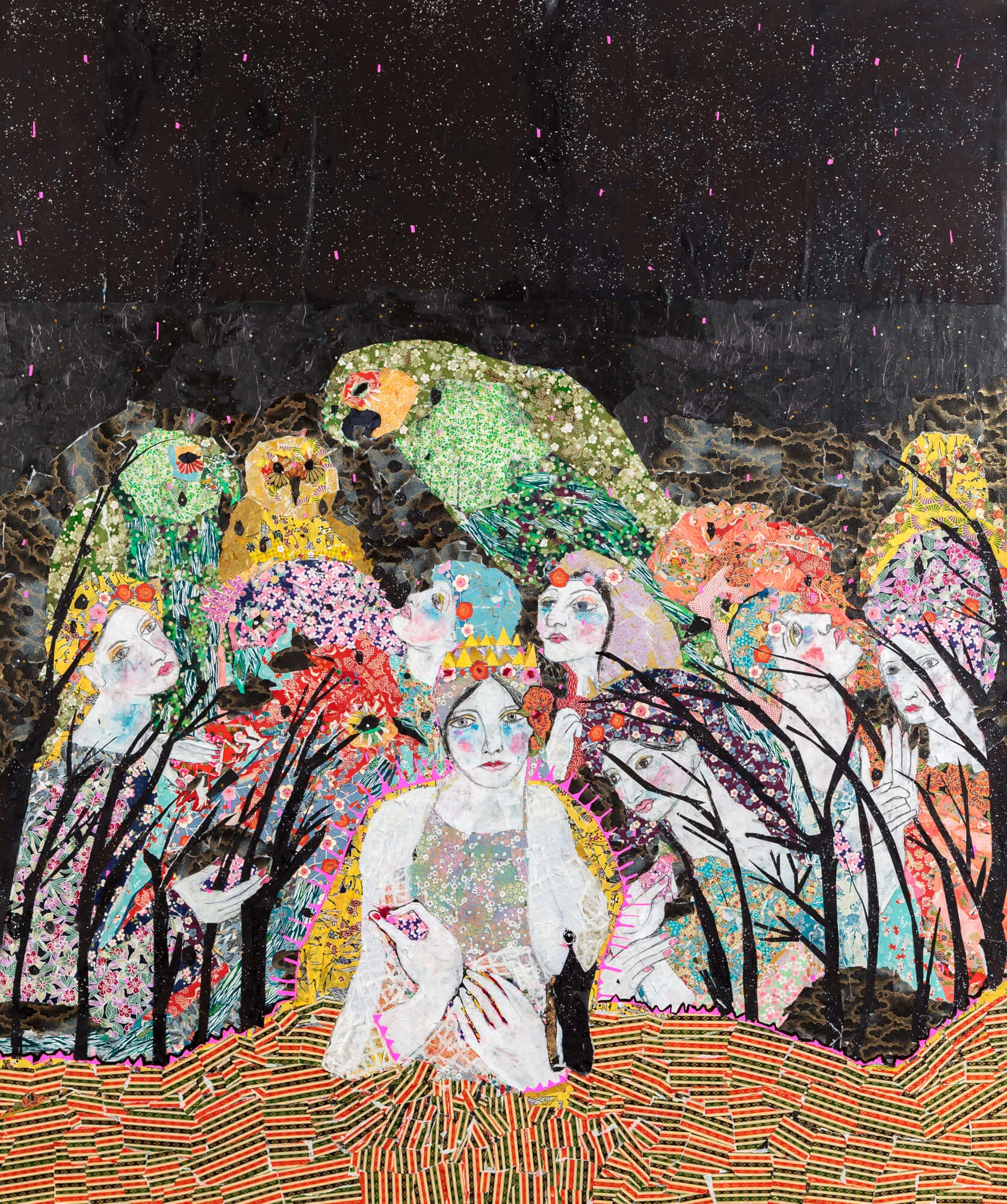

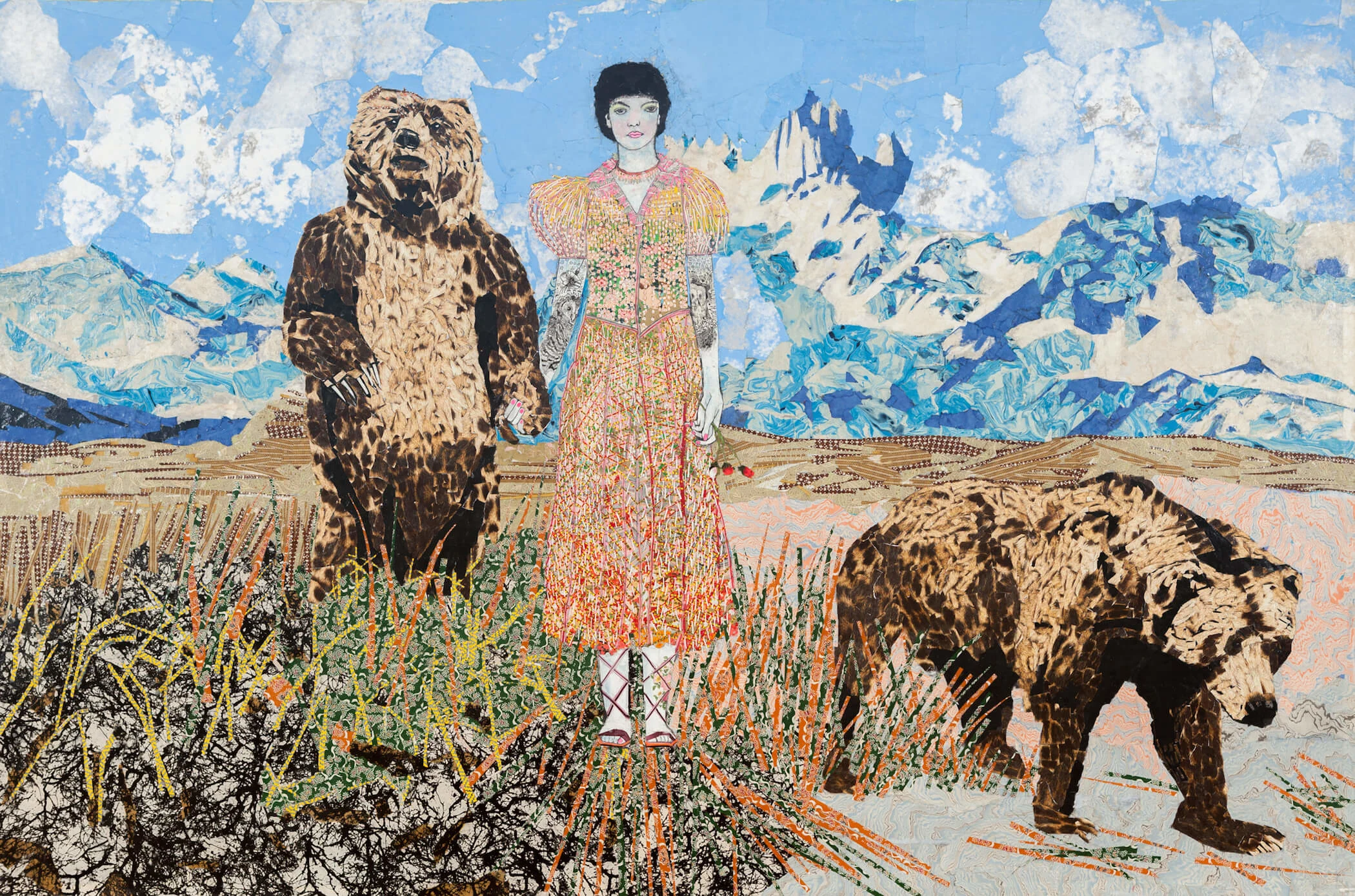

Maria Berrio wants to push collage to its limits. She cuts and tears small scraps of patterned paper to build abundant worlds on canvases bigger than herself, where tribes of women and children live in harmony with nature. “With each series, my goal is to discover even more possibilities,” she says.

Always drawn to pattern, Maria used to conjure designs with wallpaper and fabric samples before she discovered decorative Japanese craft paper and began to collage with it. “It was challenging in the beginning, to contend with all of the possibilities and adopt a new way of thinking,” she says.

The majority of her paper collection comes from Japan while the rest is sourced largely from the global south – Brazil, Thailand, Nepal and Mexico. For some artworks she’ll seek out a certain pattern that fits her vision for a piece, for others she lets the beauty of the paper inform what she creates.

“Serendipity has always played a part in my art,” she says.

My scenes are set in the moment of an imagined story, but never in a specific time, and always in a fantastic utopia.

The designs which appear on Japanese paper were based on the motifs of kimonos. In Maria’s works, the patterns find their way back into clothing in the technicolor dream dresses that grace her women.

But instead of using a pattern as it exists, Maria manipulates its symmetry by cutting it into shards and reassembling it, so it’s less neat and more organic.

She also draws on and around the patterns with charcoal, color pencils and inks to make them even more intricate, dense and detailed.

Her ink-stained skies are created in a wash of watercolor. Maria’s artworks – which she refers to as paintings – are set in lands of blue-marbled mountains or forests of mottled bark, where folk tales play out and reality is smudged.

“My scenes are set in the moment of an imagined story, but never in a specific time, and always in a fantastic utopia/dystopia,” she says. They could be scenes from long ago, when humanity lived at one with nature, or they could come from the future, where civilization has crumbled leaving only a few artifacts of human infrastructure — the last-standing wall of a crumbled house or an abandoned train carriage.

There’s a wildness to the women who inhabit these jungles, mountains and strange dwellings where golden creepers climb the walls. They wear flowers and reeds in their hair, tattoos on their skin and shawls made of bluebird feathers. They hold hands with bears.

“While my work isn’t really autobiographical, I paint idealized parts of myself in the women I create.” Maria says. “These are women I want to be: strong, vulnerable, compassionate, courageous. I aim to represent these idealized notions of femininity, and to explore what that means.”

In Born Again a woman stands in tall grass with a jaguar draped over her shoulders like a docile house cat. A tiny bird is perched on her fingertips. “The animals serve as companions to this journey of womanhood,” Maria says. “They have different significance depending on the painting.”

Their relationship is reciprocal: at times the women are the protectors of the animals and at others the beasts are their guardians. In Nativity, new-born babies are visited by an elephant, a wolf and a flock of birds rather than three wise men. Birds, specifically parrots, play an important role in Maria’s work, as symbols of freedom.

The themes and sources can be as disparate, cut-up and reattached into something as new as the paintings themselves.

Born and raised in Bogotá, Colombia, her homeland too informs the worlds she creates in her work. “I grew up in a country of natural splendor, of lustrous colors and rhythms, of warm people, a rich culture and history,” she says. “But it’s also a land of breathtaking violence and disparities of wealth.”

Now based in New York, she sees Colombia in a new light and has worked themes of place, home and migration into her recent pieces, ideas which have both personal and political significance.

“The imagined people in my paintings are displaced and are seen in preparation for their travels, in moments of transition, and in states of uncertainty,” she says. “I incorporate an eclectic range of symbols, rituals, and myths into these scenes to imbue the figures with hope and power during times of upheaval.”

Real or imagined, borrowed or retold, Maria mixes mythologies in her work as layered as the pieces of paper that create them. Her reading and research shape her ideas, and, “my own invented histories fill in the rest.”

“They’re a hybridized hodgepodge of ideas I mixed together. The themes and sources can be as disparate, cut-up and reattached into something as new as the paintings themselves.”

Lately, Maria has been moving away from frenzied pattern towards something calmer, but the ambition for her art remains undimmed. “It isn’t providing answers, but the sense there’s a deeper answer just out of reach,” she says. “All worthwhile art does this.”

Words by Alix-Rose Cowie.