These days, it’s hard to imagine navigating your way through a city without using your phone. Maps have become part of our daily lives, easily accessible at the touch of a button (or the swipe of a finger).

But map-making, part art, part science, has a venerable history, and it’s the classic maps of the 19th Century that inspire the work of artist Malala Andrialavidrazana.

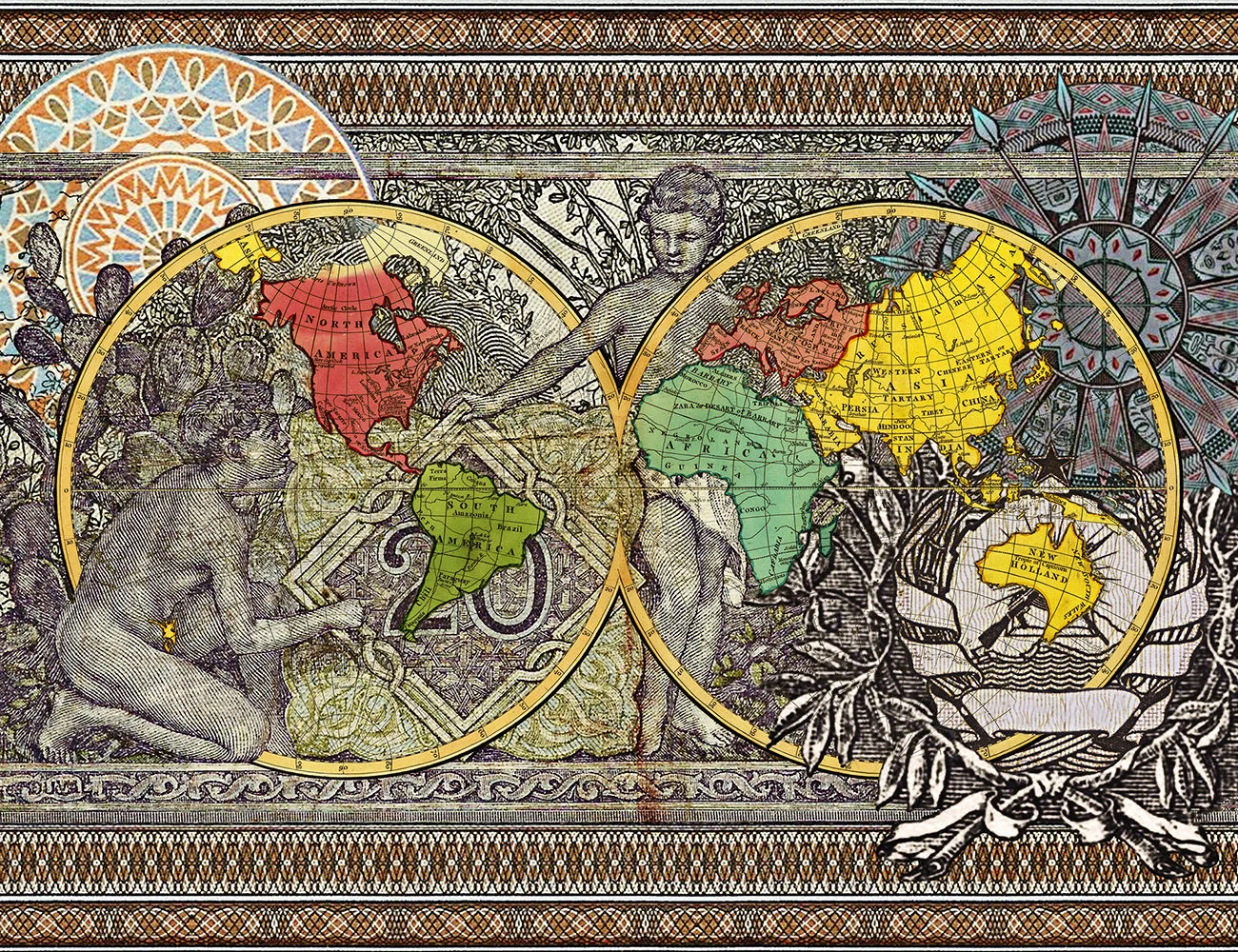

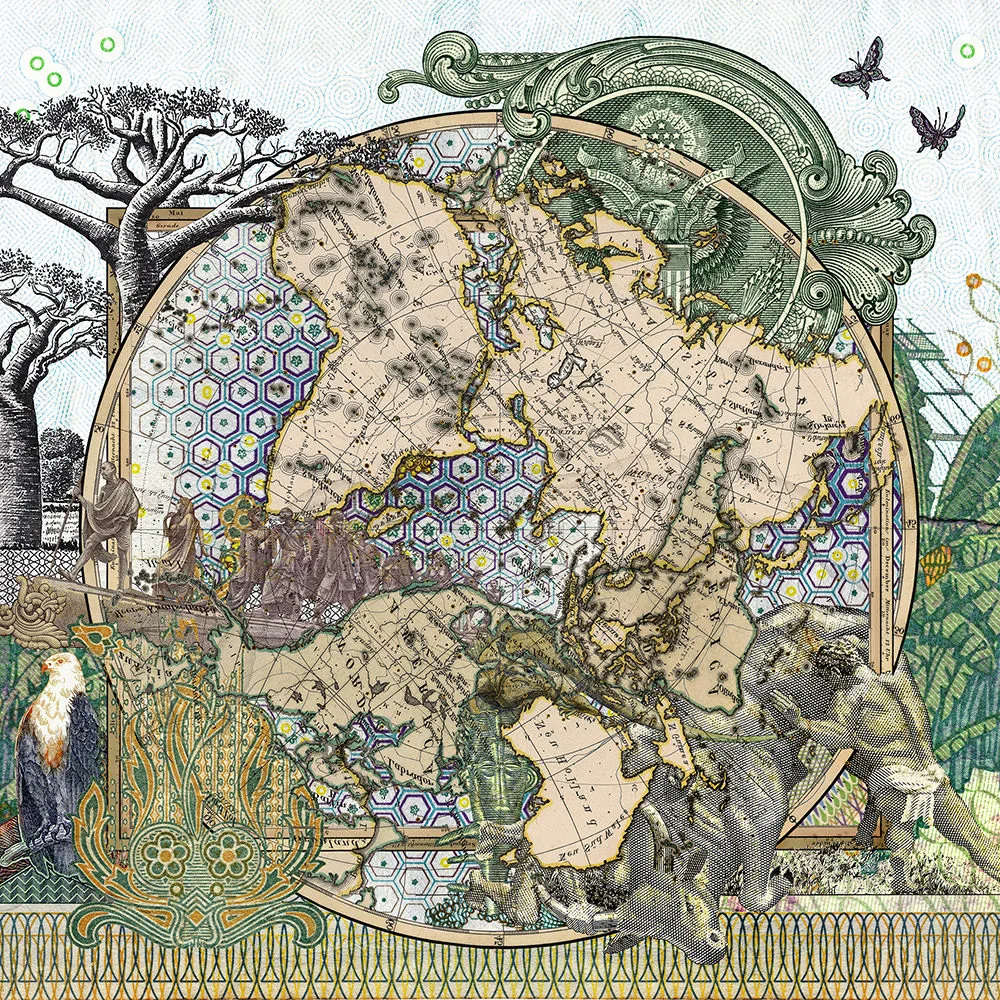

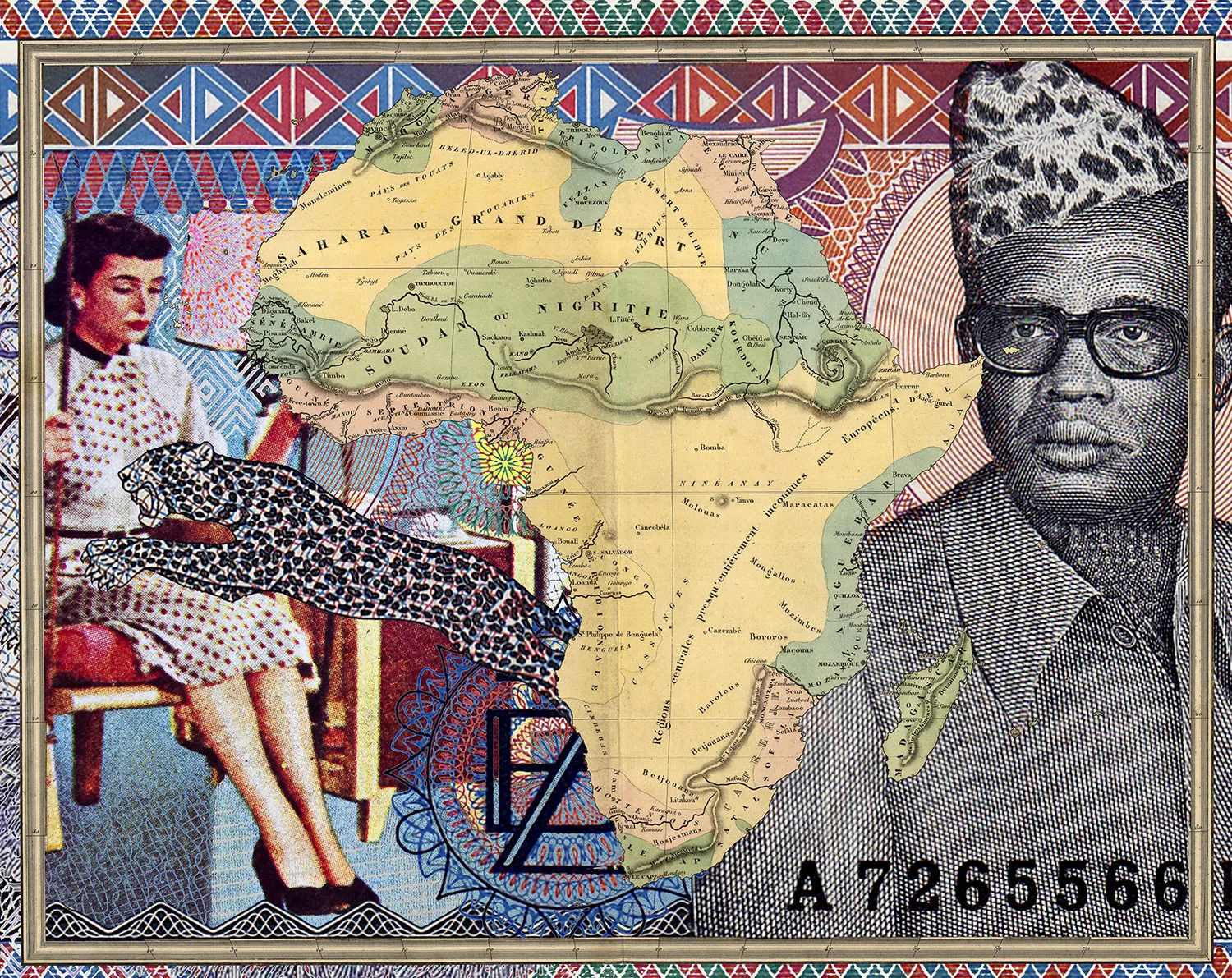

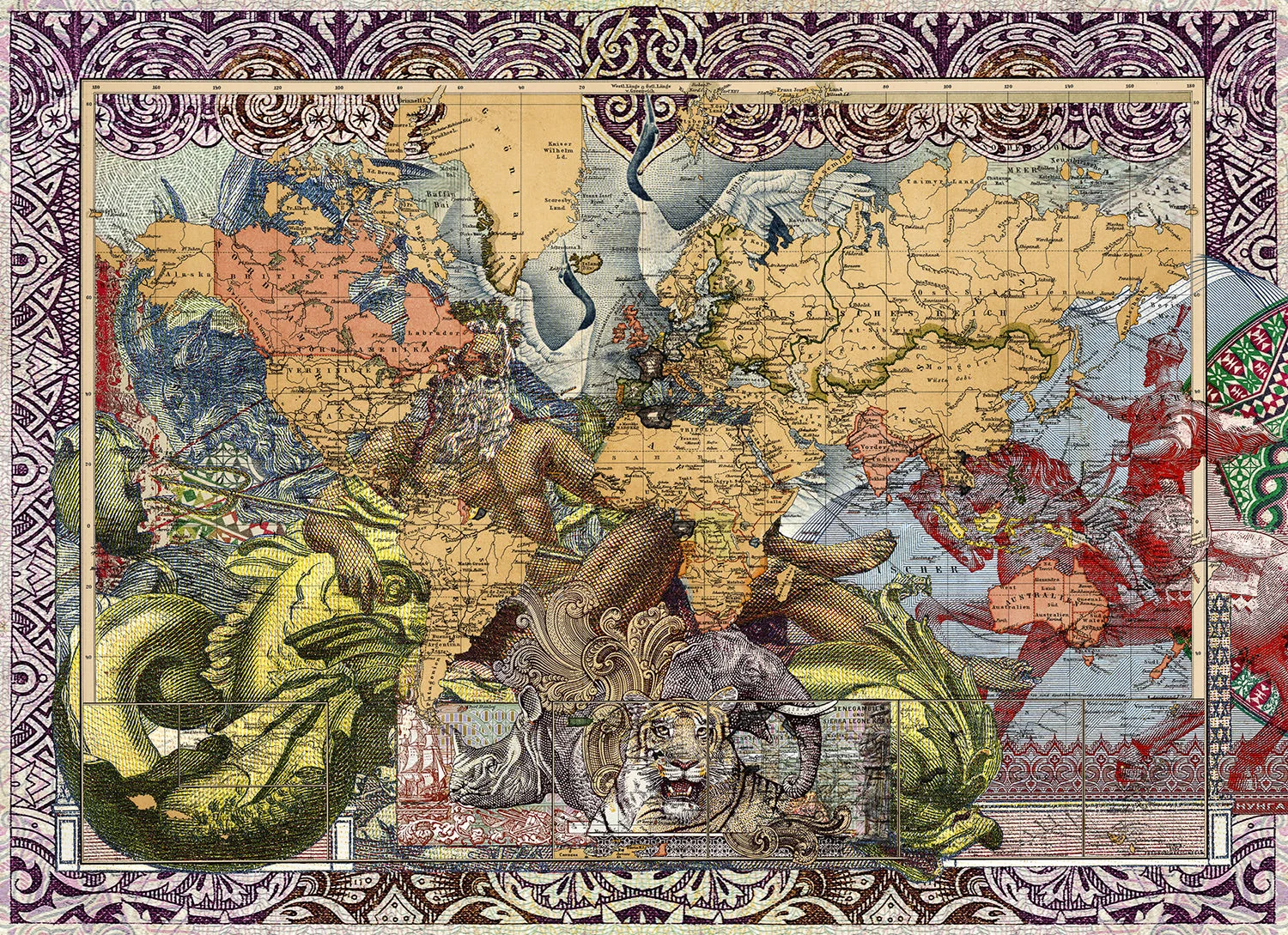

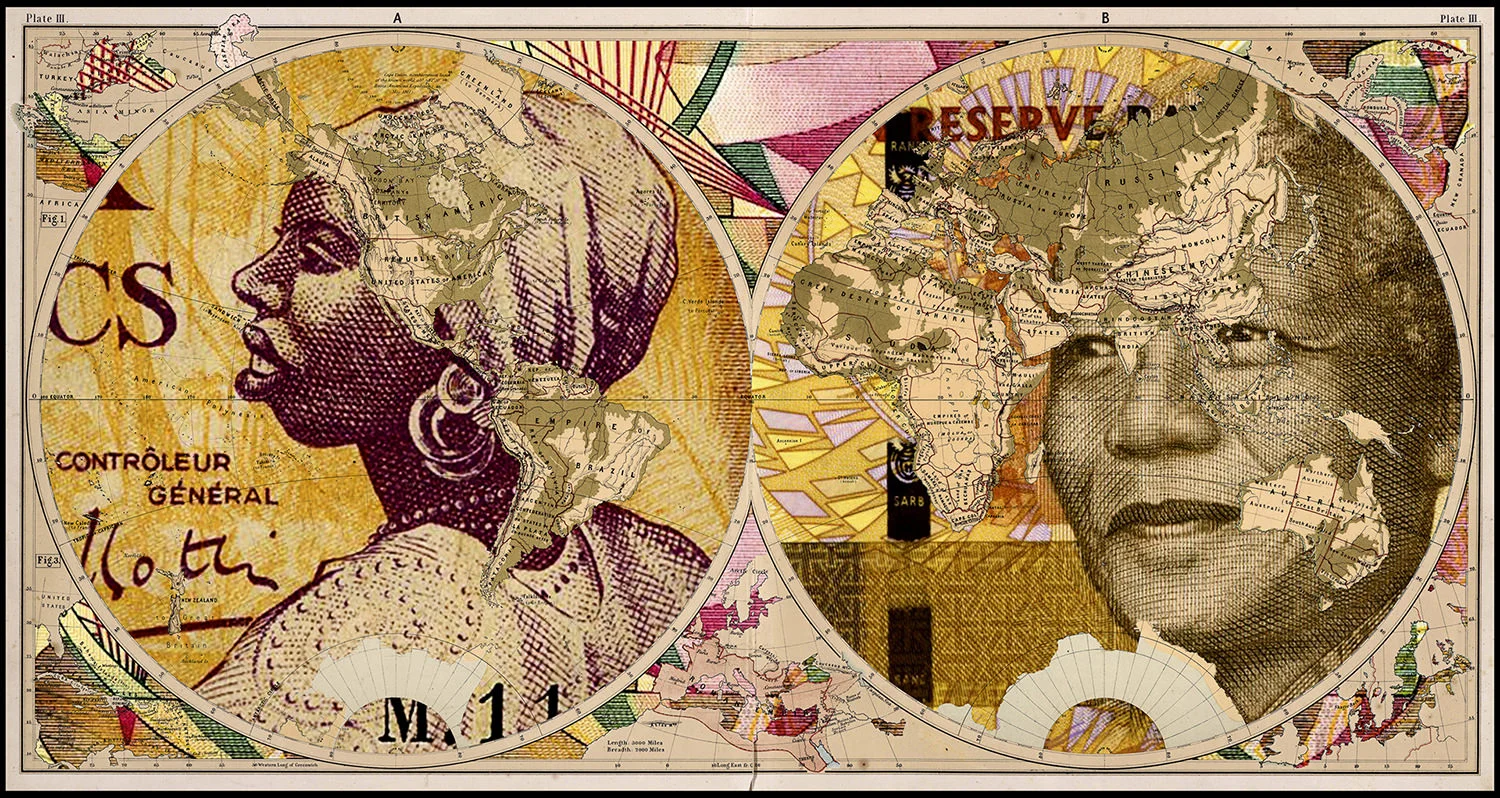

In her series Figures, maps take center stage, but she modifies the maritime parts by adding stamps, banknotes, album covers from her teenage years and iconic cultural figures like Nelson Mandela.

The result is a wonderful display of Malala’s views on the influence of globalisation – so detailed they dazzle the spectator.

Now living in France, Malala was born in Madagascar, an island where Asian as well as African cultures collide, cohabit and collaborate. This very naturally led to an interest in how different people see the world.

For Malala, vintage maps are snapshots of our history. “In the beginning of the 19th Century, big parts of the world were unknown,” she says. “But with the increase of exploration and globalization, more and more detail emerged.

“I started making these pieces to get a better understanding of our world. To me it is interesting to look at them closely and read all the information embedded, and also get the possibility to tell other stories with them.”

This specific period fascinates her because it was the age of empire building. “Cartographers were mostly commissioned by the Western powers,” she explains. “So maps were used as political tools, to claim territory – cultural aspects as well as superiority.

“Right now, we use them to orient ourselves and move around, but during that period they were used by the main powers to say – this is our’s.”

By adding new elements like stamps, foreign currencies or cultural references, the artist wants to transcend the idea of borders and ownership. “These maps tell the story of the whole world. Even if they were made by a specific power, the territory belonged to all the populations around the world. It is a shared global story. The world belongs to everyone.”

And so her version of our planet is one that moves beyond those early cartographers’ interpretations – she wants to give the viewer the freedom to rethink their own story.

“I always wonder how I can picture the world as I see it. The focus of my art is about how to get out of the cliche. How can you change people’s minds when there are so many stereotypes?” she says.

“Even if you build a picture full frame, it is important to step out of that frame to leave a possibility for any individual to recognize himself.”

And Figures does exactly that; by taking inherently political elements like maps and completely repurposing them, the artist erases traditional borders to tell our world’s story.