Most creatives will recognise this scenario. Feeling overwhelmed by a project and not knowing where to begin, you turn to something (anything?) else to kill some time. But in that random act, you find a spark that fires your next big idea.

That's exactly what happened to Indian designer Khyati Trehan. Challenged by her tutors at the National Institute of Design (NID) to create a poster about someone interesting, she went to the college library and ended up leafing through The Ten Most Beautiful Experiments by New York Times science writer George Johnson.

She came across a chapter about William Harvey, a 16th Century English doctor who first explained how blood flows around the body . From there, she found a diagram of a heart that reminded her of the infinity symbol, and this reminded her in turn of the letter W, bringing her neatly back to William Harvey.

“I mentally combined these two occurrences to integrate W and the blood circulation diagram he discovered,” she says. “I guess some part of my brain was still working on figuring things out when I wasn’t.”

So William Harvey became the subject of her poster, and a year later, when she was looking for a new assignment, she decided to try and complete the alphabet through a series of typograhic posters that celebrate different scientific breakthroughs.

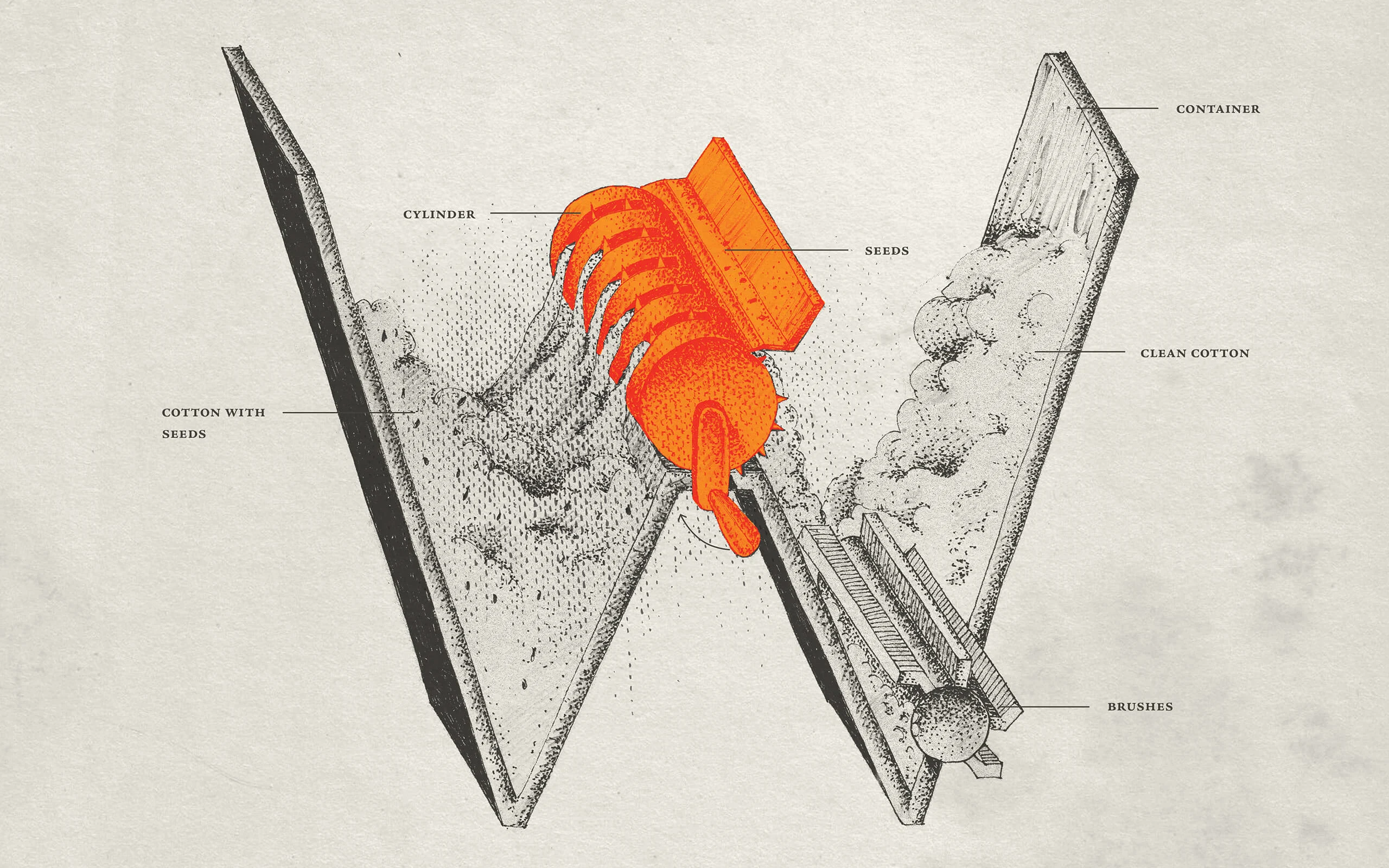

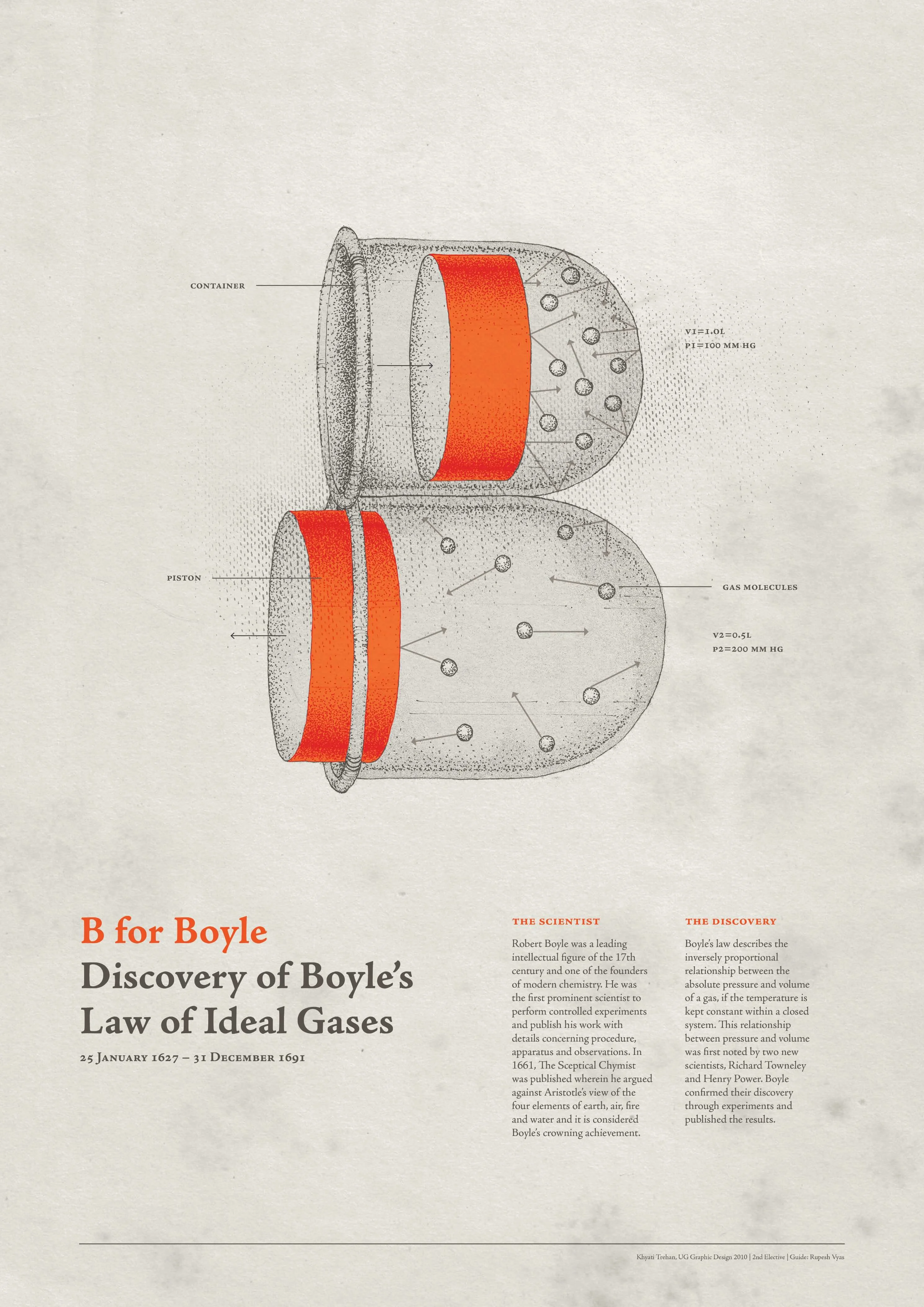

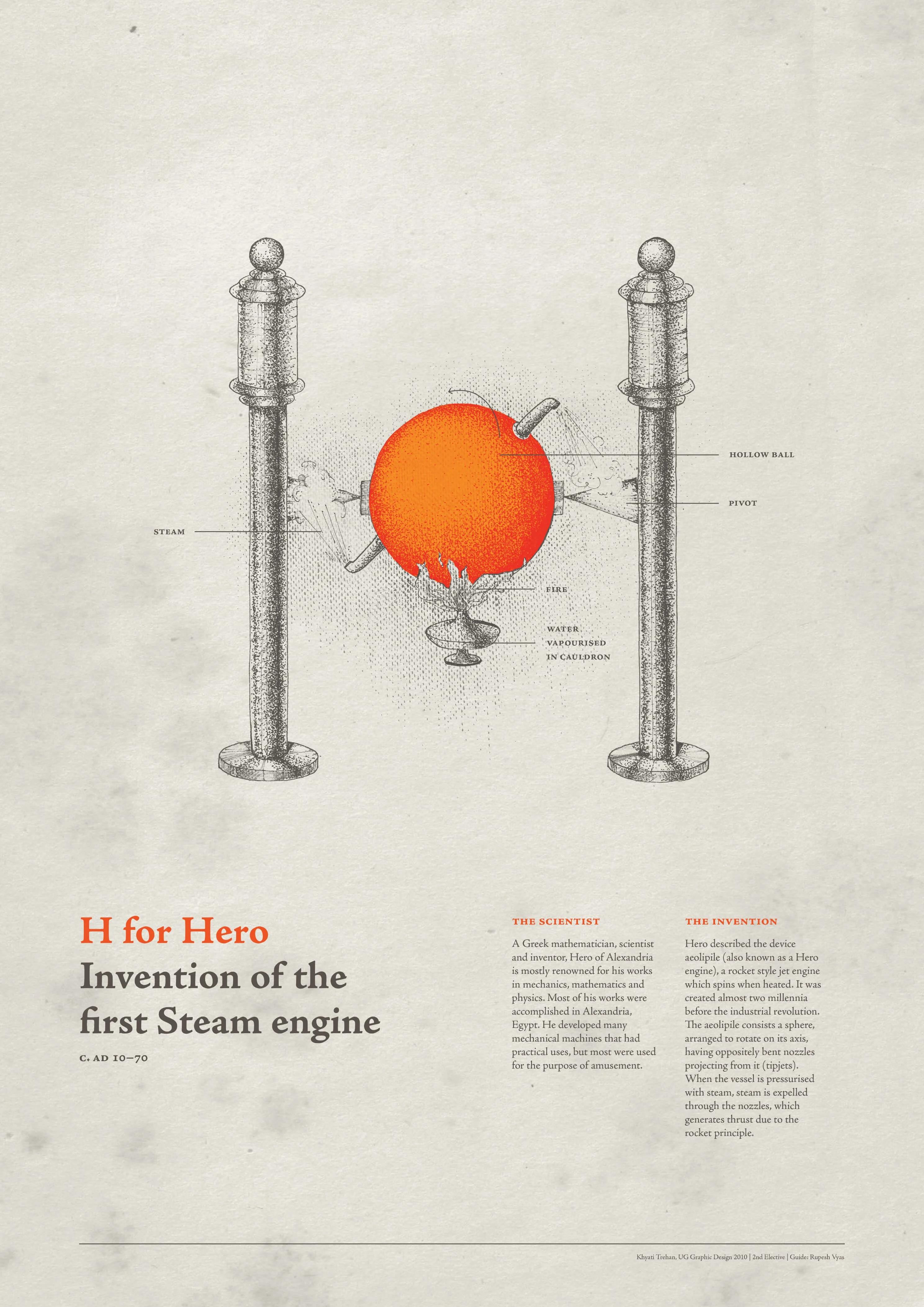

Her project The Beauty of Scientific Diagrams begins with A for Archimedes and his water screw — a machine used to transfer water from a low-lying area to a higher one — and ends with Zworykin’s Iconoscope, the first practical video tube used in early television cameras.

I wanted to make sure the illustrations didn’t sacrifice scientific accuracy for aesthetics.

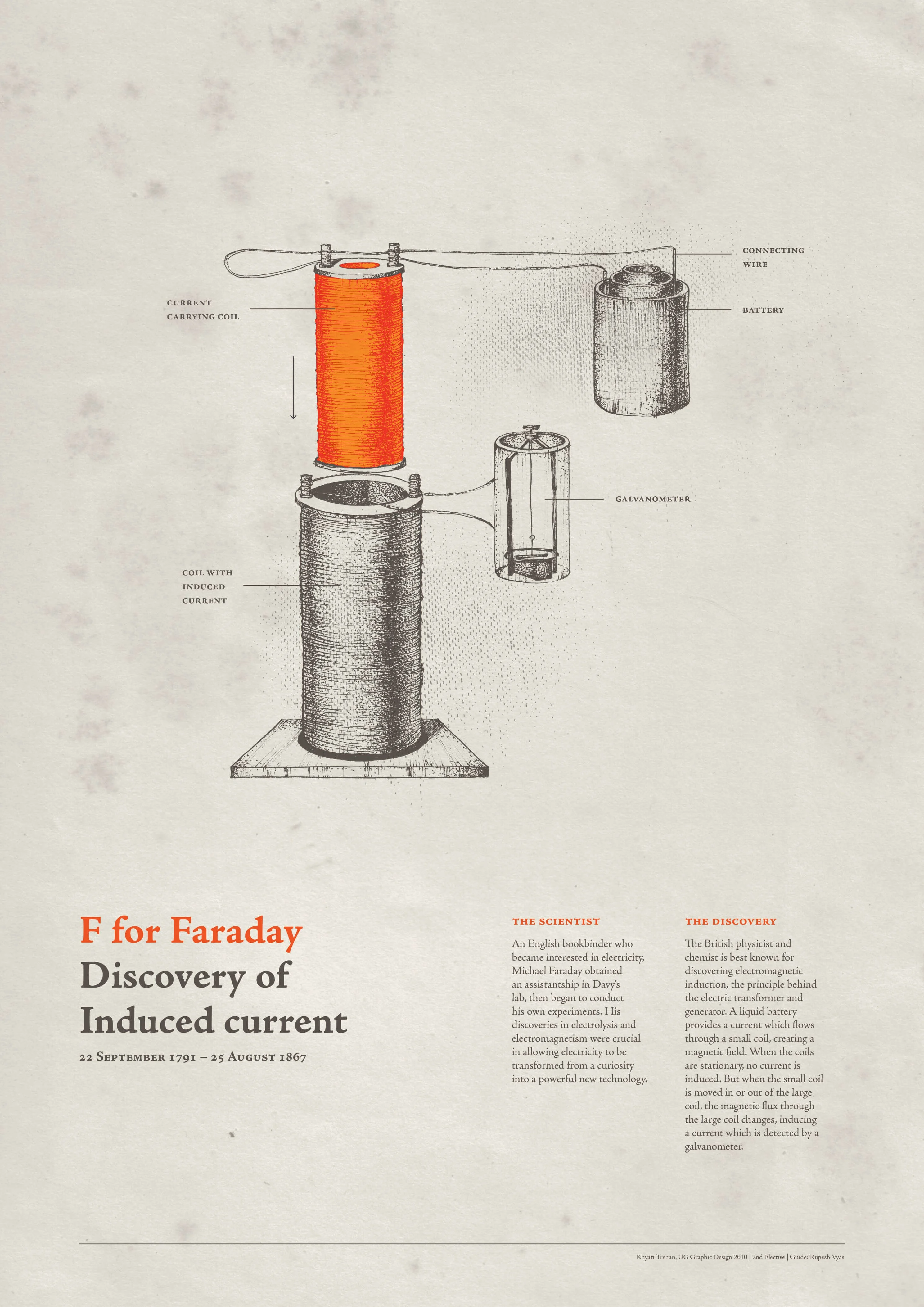

Khyati spent hours poring over patent drawings and scientific textbooks looking for suitable inventions she could turn into visuals that worked in the series.

“It was a bit like a barter system,” she says. “Who will buy my goat in exchange for their cow? Which inventor drew up a diagram that is similar to their own initial? It took me anywhere between five minutes and five days to hunt for this double coincidence of wants to decide who I’d be illustrating for each letter.”

Even though Khyati had to distort the diagrams to form the letter shapes, she wanted to make sure the illustrations "didn’t sacrifice scientific accuracy for aesthetics.” If someone was to build a physical model based on her letterform diagrams, she wanted that model to work.

This meant Khyati had to hit the books to fully understand the scientific concepts she was dealing with before messing with them. It was worth it – the resulting images are extremely satisfying. “I love that they work, that one image holds so much meaning,” Khyati says.

This appetite for accuracy came at a cost though – in this case three letters she couldn't make fit. “It was so tempting to just squeeze a diagram into these letters to have a finished product,” she says. “But I’d be failing the brief I made for myself if I did that. So I decided to practice some restraint with P, Q or X, rather than distorting them to the point of nonsense.”

It's hard for Khyati to pick favorites, but she considers the F for Faraday her most successful letter (it depicts his discovery of electromagnetic induction). “While some letters had to be pushed and pulled, wires extended, stands elongated," she explains, "the circuit that explains induced current was left unaltered."

The illustrative style of her letters comes from the research material she was immersed in. “Something about the imperfections of the old patent drawings and sketches felt really tactile,” she says, “and the style reflected the limitations of the tools back then. I tried to recreate that arduous process by making life difficult for myself and painfully stippling every letter.”

Something about the imperfections of the old patent drawings and sketches felt really tactile.

Ever since coming across The Beauty of Scientific Diagrams in the library, Khyati has fallen in love with creating meaning by finding relationships between seemingly unrelated things. “It’s as if every object, person and concept on the planet is connected by invisible strings that you walk through, and you suddenly trip over one, and that connecting string becomes visible,” she says.

“That string is my idea of an idea. Since this project started, my practice has been a lot about drawing parallels and hunting for invisible connections.”