Each of Kent Iwemyr’s paintings tells a story. He’s spent most of his life in the small Swedish town of Hallstahammar and his paintings are infused with his experience living there, telling the tales he’s witnessed himself and those he’s been told over the years. Here, he walks Joe Zadeh through the thought behind five of his favorites.

Images courtesy of Galleri Magnus Karlsson.

There is a theory that floats around from time to time that you do not need to leave home and travel to learn about the world. If you just stay in one place long enough, you will learn something about everything. The Swedish artist Kent Iwemyr has lived almost his entire life – except for a few years here and there – in a small post-industrial town in central Sweden called Hallstahammar, where he was born in 1944. “It’s special for me to live here,” says Kent, “because I have always lived here.”

His early life was spent working in forests, as a building engineer and then as a teacher, before coming to art later in life. He lives in a 200-year-old house in which he has converted a second kitchen into an artist studio from where he’s created all of his works. He paints in a naive style – “If they are too good, they are not my paintings anymore; I want them to be a bit bad,” says Kent – and depicts rural scenes witnessed first hand around Hallstahammar and the surrounding region, as well as stories he’s heard others tell about what has gone on there.

Quintessential paintings include a group of marching men carrying flaming torches over the snow into a deep black forest, villagers gathering around a boxing match in the town square, and lovers twirling each other’s bodies at a half-empty village hall dance. These works have come to be seen as a precious documentation of a rural life that is quickly disappearing in 21st Century Sweden, and he has been exhibited in solo and group exhibitions around the world. There have been comparisons to the modernist master, Marc Chagall, but his visions are also subtly reminiscent of his fellow Swede, the film director Roy Andersson.

Like Andersson – whose trademark is wide and expansive camera angles of everyday life – Kent rarely paints his subjects up close. Instead, you look down on his scenes from afar, like a voyeur twitching the curtains at a second floor window. In every image, there is an overriding sense that where you are is a huge part of who you are. And this distant take on life gives everything an air of both comedy and tragedy, that seems to echo Rimbaud’s words: “Life is the farce we are all forced to endure.”

Pureness and Chastity (2013)

“Every Friday night, we would meet at this sauna, and talk for hours about everything between heaven and earth,” says Kent. “We had a tradition of whipping each other with a bunch of birch twigs, which is a habit that originally comes from Finland.” His style has changed very little from when he first began painting like this, around 30 years ago. “After leaving art school, I made abstract paintings. Then, one night, I found an old painting I did when I was at school: a troll in front of a stone. I got the idea to paint like I did when I was a child, and mix it with the knowledge I now had from my art education. And that’s what I’ve done ever since.”

It’s special for me to live here, because I have always lived here.

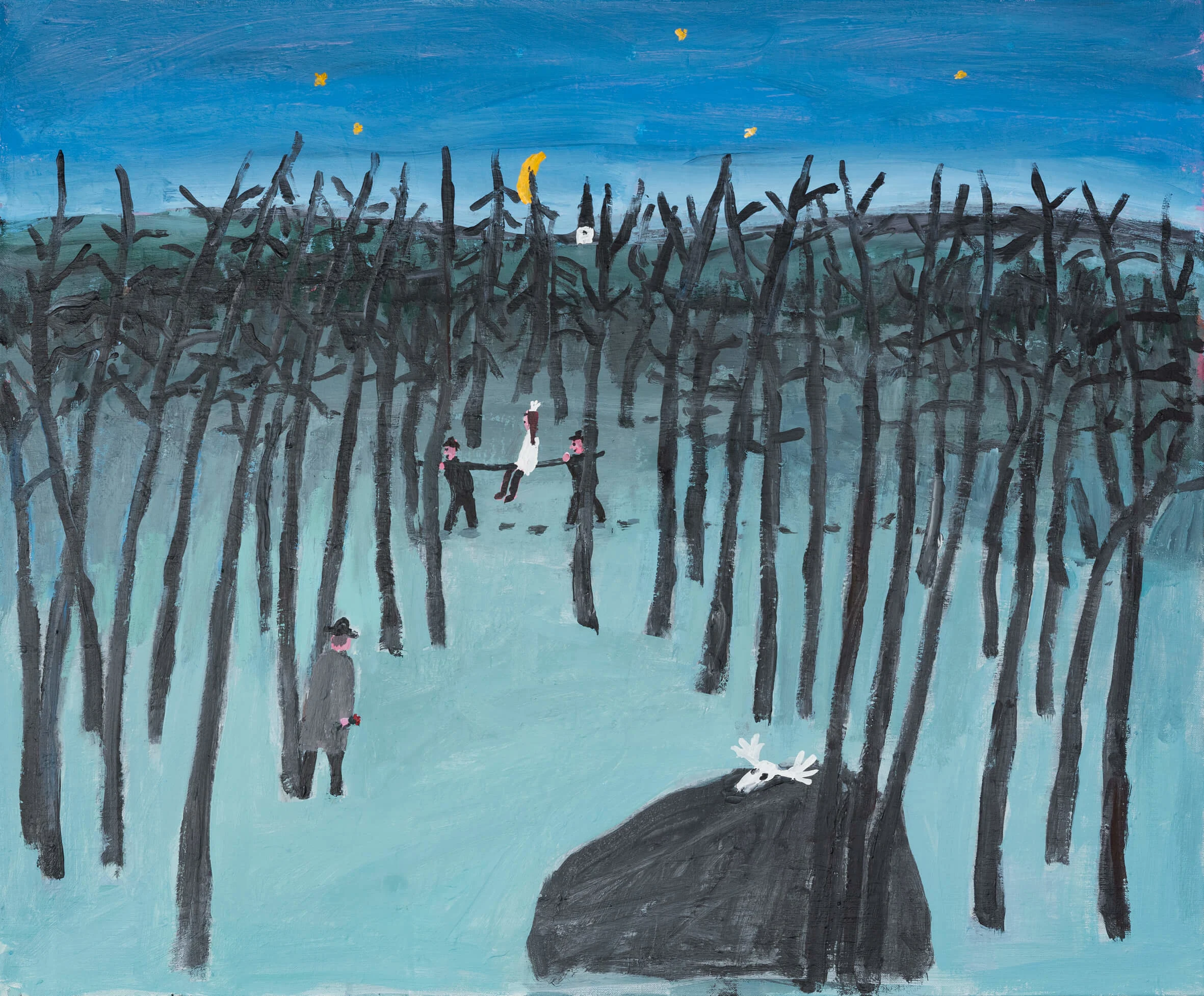

Killing Your Darlings (2018)

Some of his paintings come from distant memories, like Killing Your Darlings which is set in an abandoned iron ore mining village he encountered during the cross country skiing days of his youth. “Like many mines in the area, it was closed and the place became completely deserted. They tried to grow mushrooms there and it worked well until it was discovered that they contained toxins from the mining. And then the place was empty again,” he said. “At last, they gave the land to a film studio – it turned out to be a perfect place for filming action and horror movies. In my painting, I pretend that Ingmar Bergman and his crew are there to make a horror movie.”

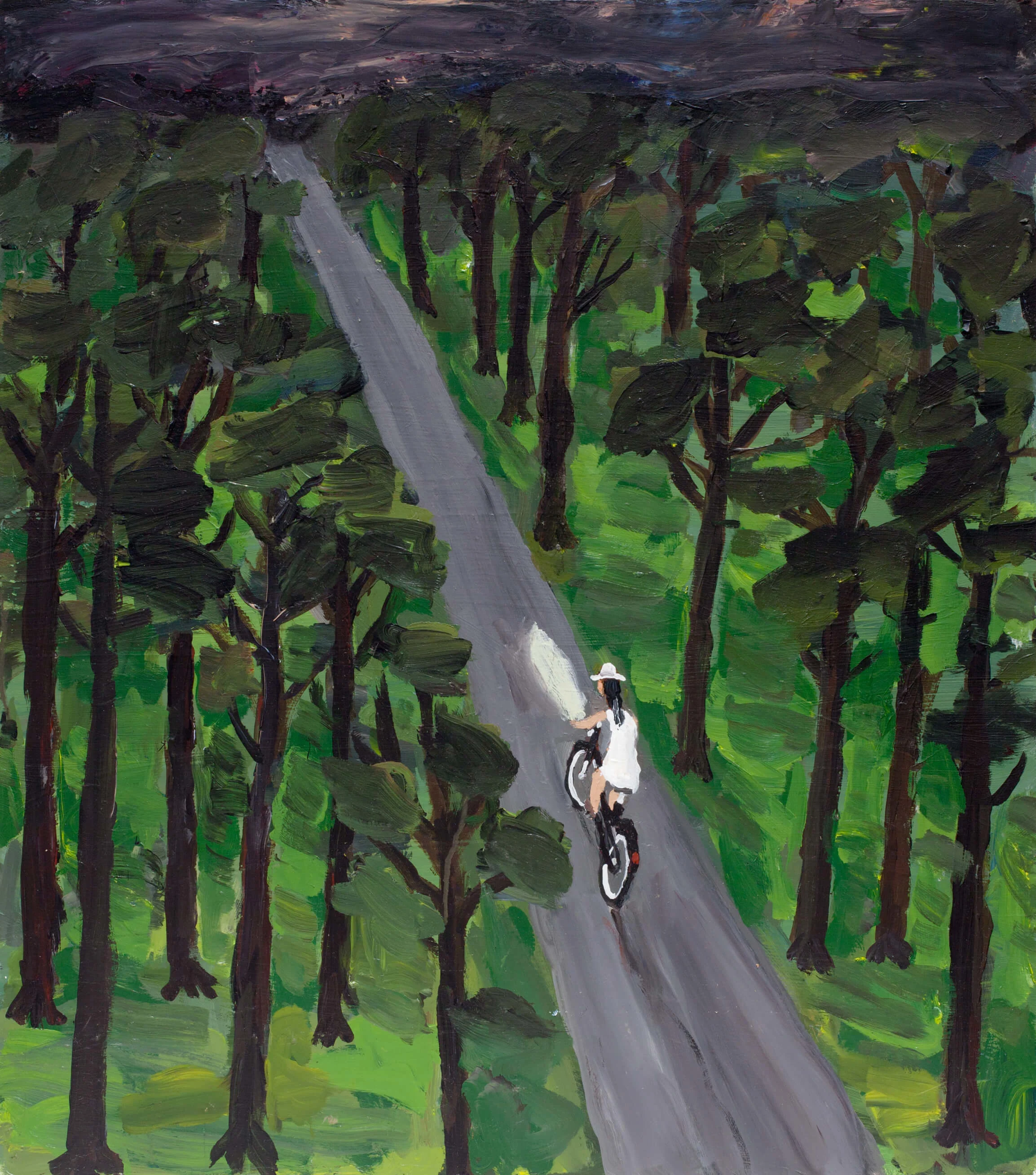

How Dare You (2019)

Climate change is a palpable reality in Kent’s hometown, and one of his 2019 paintings showed Greta Thunberg riding a deer with a wooden sword in her hand, with a title (How Dare You) inspired by her historical speech at the United Nations Climate Action Summit. Snow is a perpetual presence in his scenes, but it is the snow of the past. It doesn’t come like it used to, anymore. “When I was young, winters were okay,” he said, “but now it’s awful. We have winters like London now. Mostly rain. Snow only on some days. I’d have to go 100 kilometers further north now to have enough snow to ski.”

False Moon (2020)

Should paintings tell stories? “I can’t say that,” Kent says, “but for me it’s important. I’m not good at writing stories, and I’m not good at telling stories, so I paint them.” False Moon tells such a story, one of a suicidal local poet who disappeared one night. “He had said, ‘I’m going into the lake,’ which meant he was going to kill himself. He disappeared into the forest and didn’t come back. So, these well-dressed men went out into the night with torches in their hands to search for him.”

Every Friday night, we would talk for hours about everything between heaven and earth.

I Did Not Become a Star, Even Though I Fought Like a Slave (2020)

“This is a story about an old neighbour of mine,” says Kent. “When we were young he was always fighting. He had an idea to become a real boxer. So he trained with the local boxing club, and at last he was ready to go into the ring. We boys were very impressed by him. We saw him in the local paper with a picture and everything. We went to the match to see him in the ring, but it didn’t turn out as he’d hoped. In the first round, he gave up. He screamed to the referee and said, ‘I give up!’ and jumped out of the ring. His career ended there. And then, a couple years later, he was killed in a drunk fight. I remember him very well; he was long and skinny.”