Some people draw with pencils. Some with charcoal, pens or paint. Keita Mori draws with thread. His huge and detailed works are made using a glue gun to stick hundreds lengths of string to blank walls. They look like architectural blueprints for buildings or other structures, but the works communicate a meaning beyond their appearance. We speak to Keita about his process, his inspiration and where the idea for this fiddly medium came from in the first place.

When Keita Mori was in his final year at the TAMA university in Japan, he tried to make a 3D sculpture of a house using thread. The experiment failed, as soon every length of string came loose and fell to the ground. He was surprised to see that the threads looked even better strewn across the floor than they had when standing upright. He moved on and forgot about it, kept busy studying at Paris’ National School of Fine Arts and gaining a masters in Fine Art at the city’s university. After graduating though, he recalled what he had seen when his old experiment failed, and picked up thread once again, this time to draw with.

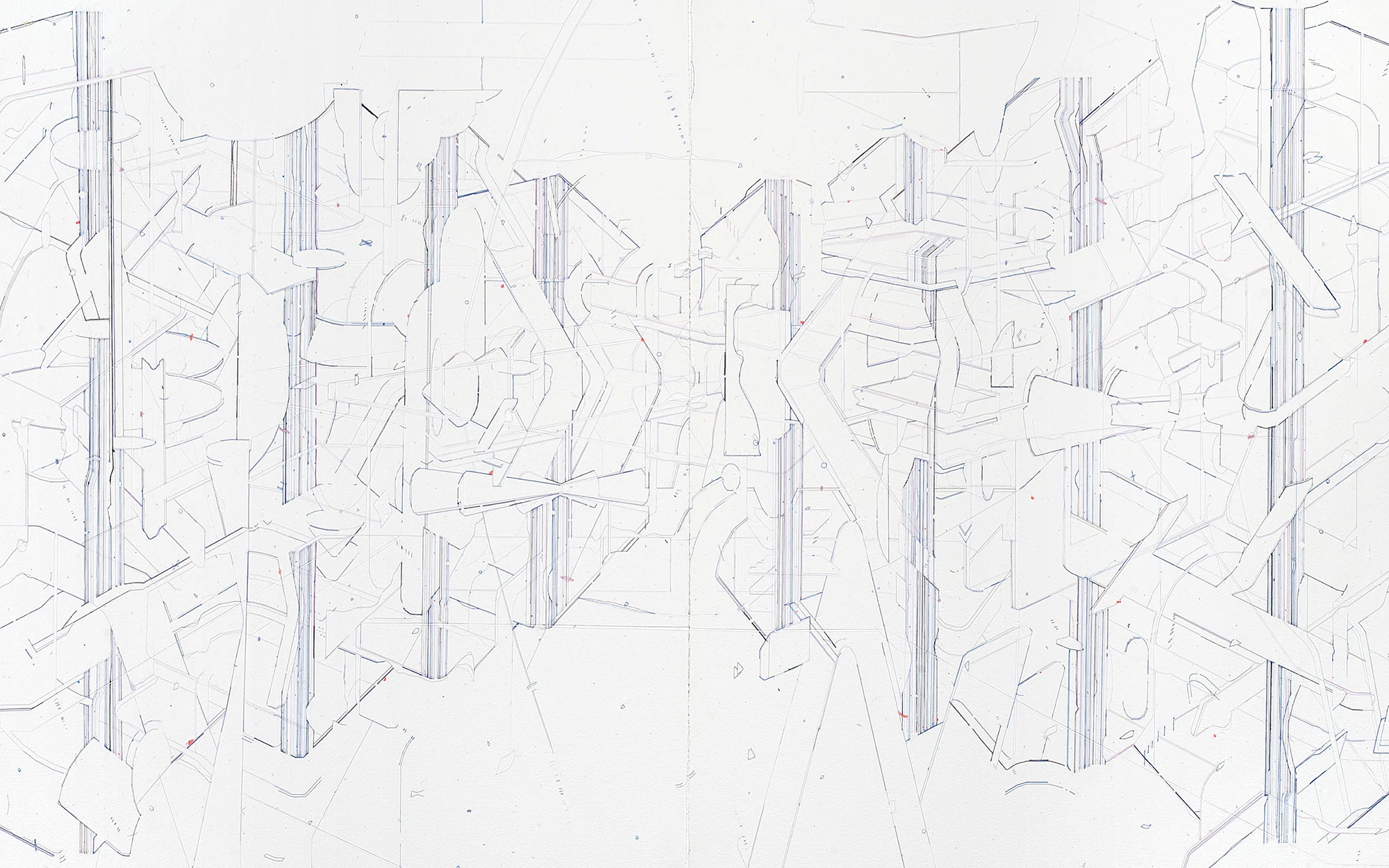

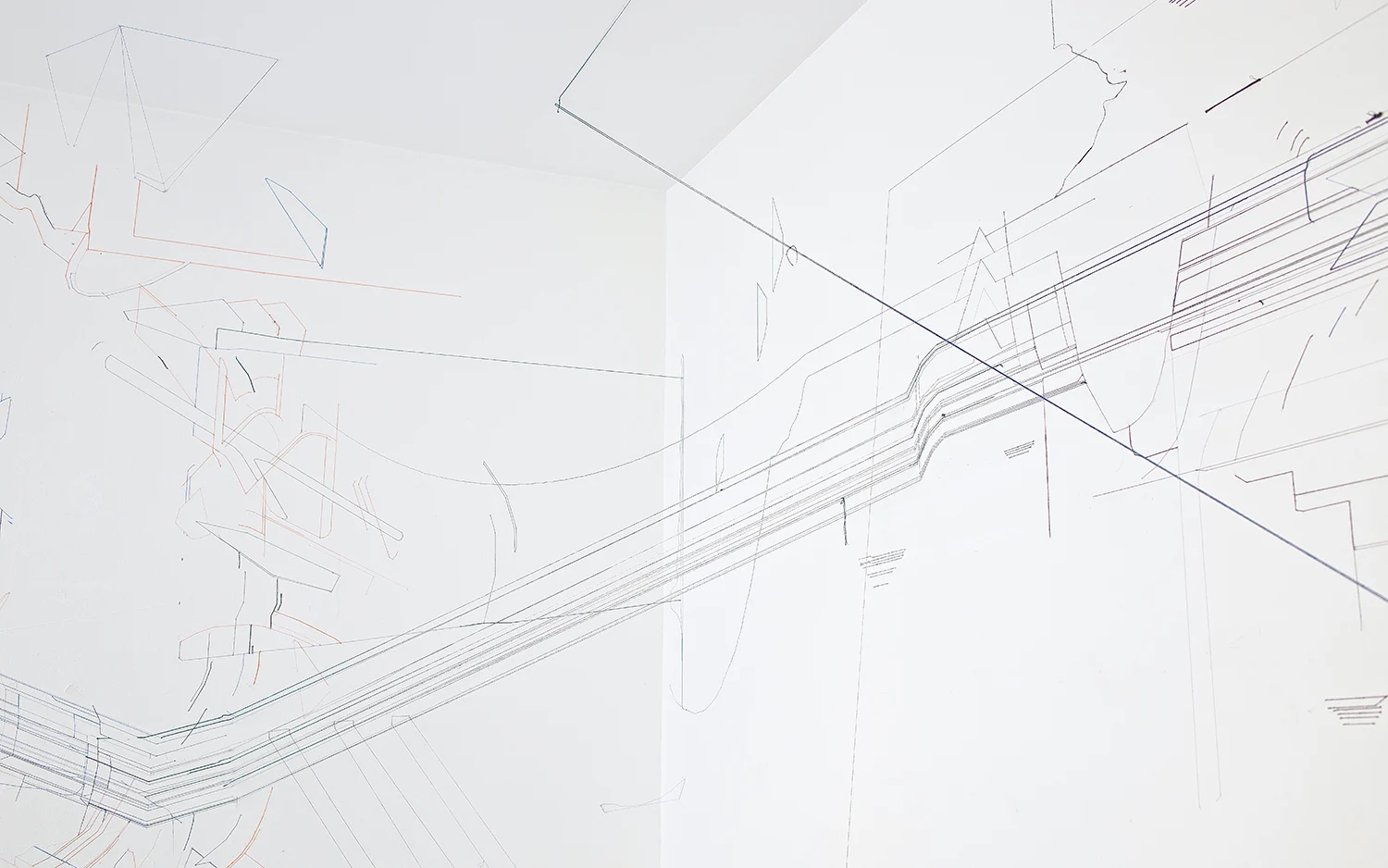

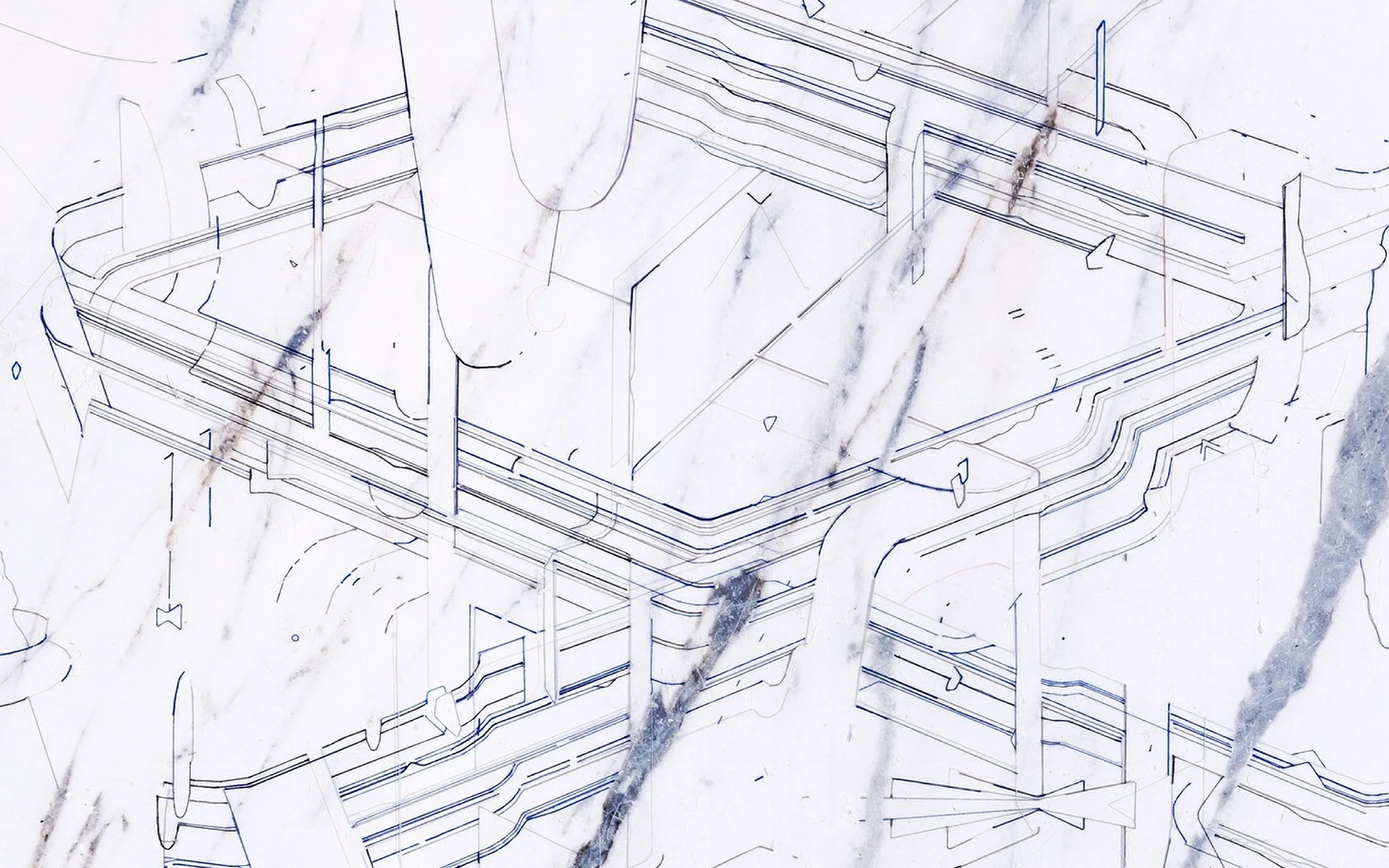

Ever since then, he’s been working almost exclusively using cotton and silk thread on walls, paper, acrylic and other surfaces. Strings overlap and interlock, and the unique works often look like floor plans for huge, complex buildings or for some sort of spaceship. Keita creates geometric representations of networks; both figurative and abstract. “These string lines can be thought of metaphorically as the building blocks of systems and societies,” he says.

But, since Keita is not actually creating blueprints for any specific or “real” structures, the meaning in his work comes more from his process and the medium he uses. Keita says that society, and all the blocks that it involves, from building plans to social structures, is often less stable than it seems. Plans can be so complex, and Keita communicates that in the complexity of the diagrams he creates. Importantly, though, his weapon of choice is thread: flimsy, breakable and slightly unreliable, as he saw in his first experiment in Japan.

In any highly controlled system, it can hardly be said that there is no possibility of an error.

He titles all of his works Bug Report, named after the message you might see on a computer screen to tell you about program errors or defects. No matter how complex and polished his diagrams and blueprints might seem, he wants to make it clear that they can still be flawed and faulty. “In any highly controlled system, it can hardly be said that there is no possibility of an error,” he says. “There are always some questions around security in this seemingly complete world. In my drawings, the thread is a material symbolizing the imperfect structure of society.”

Writing in 2017, Akira Tatehata recalled a thread work Keita had created inspired by the reactor of a nuclear power plant. “Keita intuitively anticipated the accident and explosions in the Fukushima nuclear power plant several years later, without knowing what would happen in the future, and without any intention of conveying political messages,” wrote Akira. This is a prime example of Keita’s works showing that detailed plans of complex systems could still lead to faults, mistakes and accidents down the line.

Nuances like speed, strength, and softness are not possible in thread.

Keita makes no sketches or plans before starting a piece. “I repeat the simple geometric patterns created in nature and scattered throughout the natural world with two types of string, expanded straight lines and naturally curved lines, creating original images,” he says. “It’s a very intuitive process.” He works fast, creating one of his huge works, about six metres wide and six metres high, in just 10 days. He adds every individual length of thread using a glue gun, starting with the most simple lines and adding more dynamic ones later in the process. It’s interesting to consider that Keita’s medium doesn’t allow for many of the intricacies that can be used when sketching or painting. “Nuances such as speed, strength, and softness are not possible in thread, and there are only two ways for the lines between points; tightening or loosening, and straight or curved,” he explains.

Every piece is just as interesting viewed up close as it is when you step back and take in the entire composition. “I can express both lage images and intricate details in each single work, so I can leave many more possible interpretations for the viewer to explore,” Keita says. “I’m trying to make work that doesn’t only have one meaning, or only make sense in one way. Because art is always awakened when it faces the viewers and grows its own relationship with them. To me, these kinds of invisible conversations are what art is all about.”