There wasn’t much of an art scene in Vereeniging, South Africa, where illustrator and street artist Karabo Poppy Moletsane grew up. But a lot of emphasis was placed on hair.

Hair salons and barbershops in the country are known for their colorful hand-painted signage sporting custom lettering and illustrations of men and women modelling the hairstyles on offer inside. Outside of animated TV shows and Sega games, it was the only artform that the young Karabo was exposed to, and it left a lasting impression.

“I remember being fascinated by the creation of these iconic signs,” she says. “Hair salons felt like home and the signage outside showed individuals that looked like my family and I – something I wasn’t exposed to in media at the time.” So whether she’s collaborating with brands like Nike or Calvin Klein, or illustrating the Google doodle for International Women’s Day, her work pays homage to these establishments and the people that make them buzz.

I see everyday Africans as the saints, heroes or sacred figures of the African aesthetic.

Karabo’s illustrations dance with pattern, bold expressive lines and irregular type all rendered in unconventional color combinations: from neon greens to oranges to deep reds. “I choose to use colors that echo an air of Afrofuturism,” she says. Organic tapered line work adds a textured effect to her illustrations.

Her characters are all stylized with a geometric nose, swollen eyes and wild swirls in their hair. They’re everyday people she encounters on the streets of Johannesburg, where she’s now based. “People that I feel embody a contemporary African aesthetic,” she says. “People that show the diversity and hybridity of our country.”

Often Karabo’s characters will be illuminated by a halo behind their heads. “I see everyday Africans as the saints, heroes or sacred figures of the African aesthetic,” she explains. “I choose to celebrate and honor these individuals the same way Byzantine artists would honour saints, heroes or sacred figures in their icons.”

You can’t separate Karabo’s work from where it’s made. Her material comes from her surroundings which she first photographs to use as reference for her illustrations. It allows her contact with her subjects, something she feels is important to maintain authenticity in her work.

“The people I illustrate are people I have had personal interactions with,” she says. “The hair salons I illustrate are hair salons I go to, to have my hair done. This personal, shared narrative gives me an opportunity to authentically celebrate and preserve the African aesthetic as I am so deeply entrenched in it daily.”

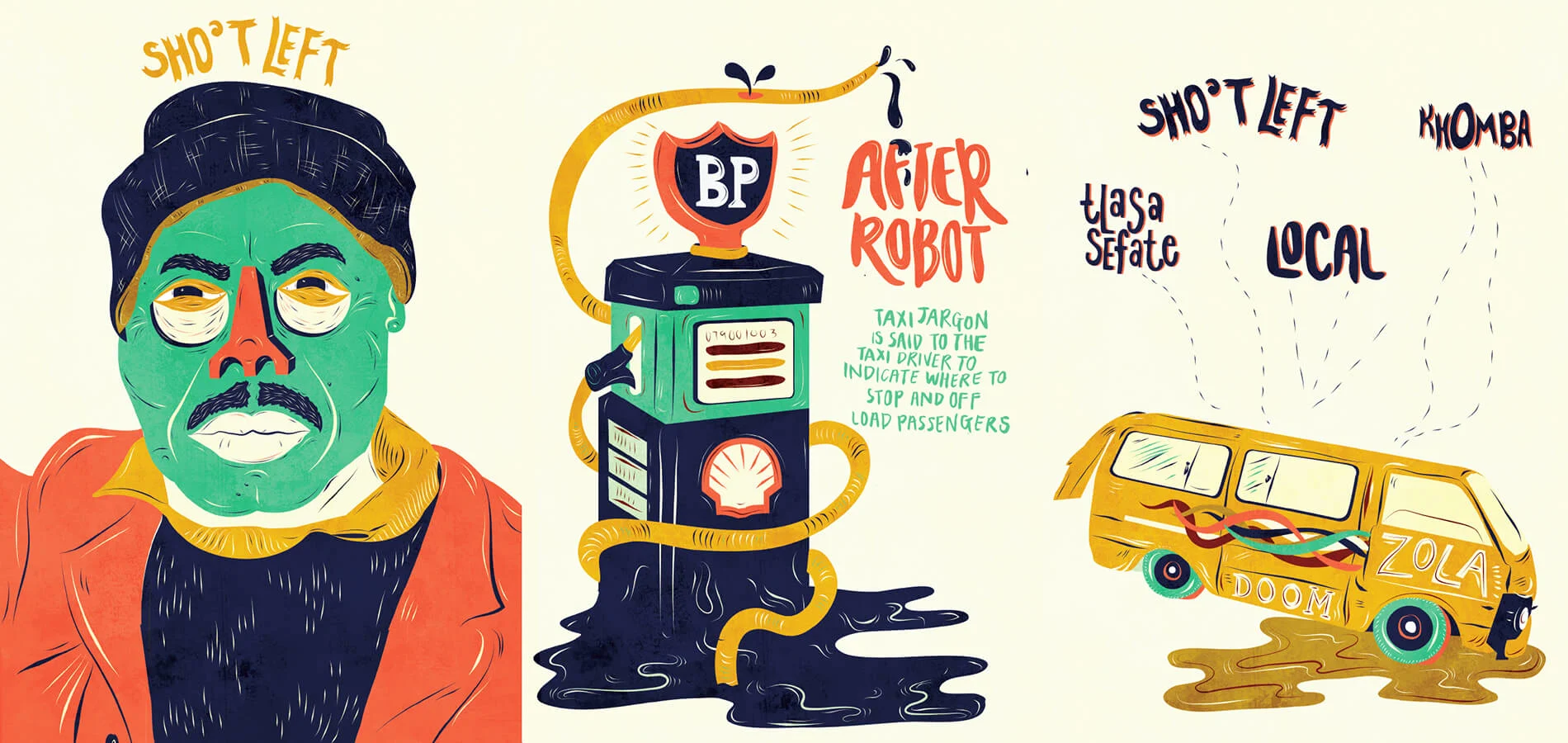

Similarly, she dove deep into everyday life working on her zine Sho’t Left. In South Africa, minibus taxis are an affordable mode of public transport and the way millions of people commute to work and home. Catching a taxi comes with its own system of hand signs and language to signal the drivers to pick you up or drop you off. “Sho’t Left” is what people say to drivers when they want to get out at the next left turn. For this project, she took a ride to Pretoria’s central business district to interview commuters about their occupations, which she then illustrated.

“The purpose of this zine,” she wrote afterwards, “was to display how unique and different South African occupations are and to inform readers about the exciting facts, tools, people, color and culture one may encounter when riding in a proudly South African taxi.”

More recently, Karabo has been introducing street art to her repertoire, creating large scale murals on buildings and basketball courts. While the internet was initially believed to be a democratic platform, high data costs keep many South Africans offline. Similarly, white cube galleries and art museums can be intimidating. Street art on the other hand is seen by the masses, moving in and out of the city each day.

“A lot of my work existed digitally for the longest time and not everyone in South Africa has readily available access to digital media,” Karabo says. ”I believe tons of South Africans are breaking boundaries and starting important conversations through their art and that street art gives equal opportunity for a large audience to experience this.”

Through murals, Karabo gives back to the culture her work originates from. “I try to make work that is as accessible as possible.”

Words by Alix-Rose Cowie.