Southern African hunter-gatherers are the most enduring population in human history, but also the most marginalized in modern Namibian society. For the past 20 years, Omba Arts Trust has worked with local San artisans in remote areas of the Kalahari desert. As founder Karin le Roux explains to writer and fellow Namibian Kelsey Corbett, she saw a way to revive San material culture through workshops that offer opportunities for skill-sharing and creative expression, as well as a source of livelihood and pride.

Film footage courtesy of Andrew Botelle / MaMoKoBo Video & Research. Photos by Karin le Roux.

There are few places in the world as inhospitable to human life as the Kalahari desert, and yet this is where the San have survived as nomads for over 150,000 years. The rains are short, the heat intense, the vegetation scarce, and historically the San would have had to cover enormous distances in order to track animals and dig up tubers for food.

Traveling in family groups, the men hunted using bows and poison arrows, while the women were skilled at gathering medicinal and edible plants. During droughts, they found underground sources of water in the desert, digging sip wells in damp sand and collecting the moisture in ostrich eggshells. San spiritual beliefs, rituals, stories and cultural histories have been passed down orally, in a number of dialects that are notable for their click sounds.

The San were forcibly displaced by the arrival of other groups in the 19th Century, including cattle farmers and colonialists, increasingly confined to smaller and less habitable areas or indentured as farm laborers. This was not remedied after Namibian independence in 1990, when landless San were resettled on farms such as Drimiopsis and Donkerbos where artisans supported by the Omba Arts Trust now live.

Founder Karin le Roux considers their loss of land as the single most devastating blow to the ancient culture of modern San, as the old ways of life are being eroded. “The current generation with whom we are working could be the last who retain some knowledge of gathering and hunting,” she explains.

“The loss of land led to the disconnection from our natural environment, our culture and identities. The people were traumatized by these sudden changes beyond their control, and this is evident in the marginalization of the San today,” says Kileni Fernando, a member of the Namibian San Council.

It is a way of connecting, a way of building chains of trust and getting people to take ownership of their lives.

Mara Britz, who has lived on the Drimiopsis resettlement farm all her life, joined Omba in 2008 when she had bead training. She recalls the high unemployment in her community, where many of the young people lived off a share of their grandparents’ small pensions. “I did not finish school, the majority of San people did not finish school, and this work that we do has given us life. We work, we get money, we eat, our children eat…We thought we were abandoned, but Omba has helped us stand on our feet.”

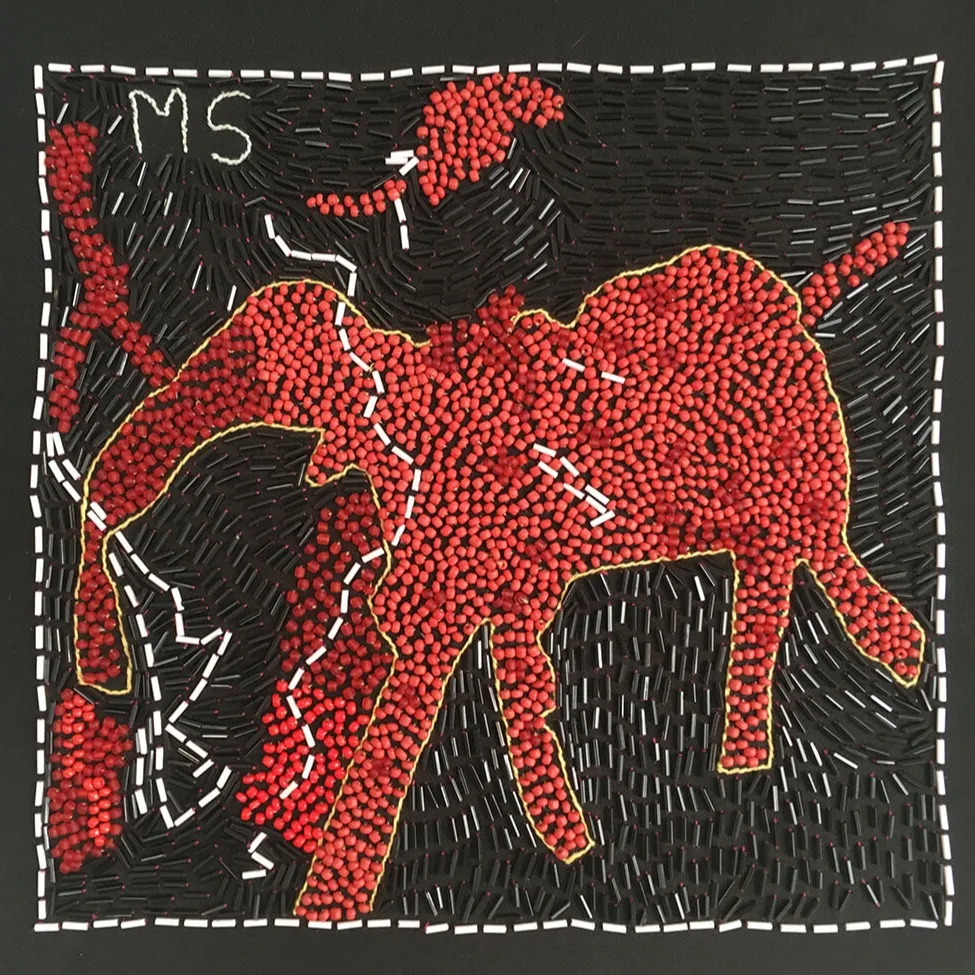

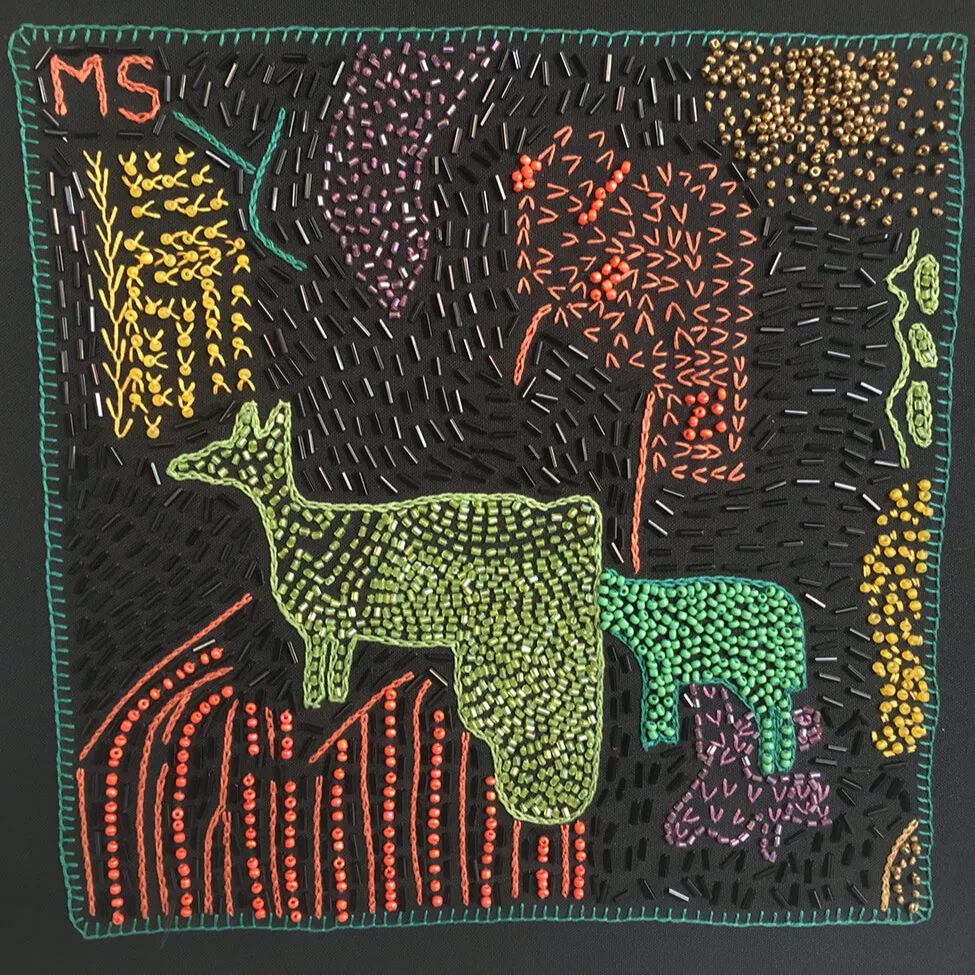

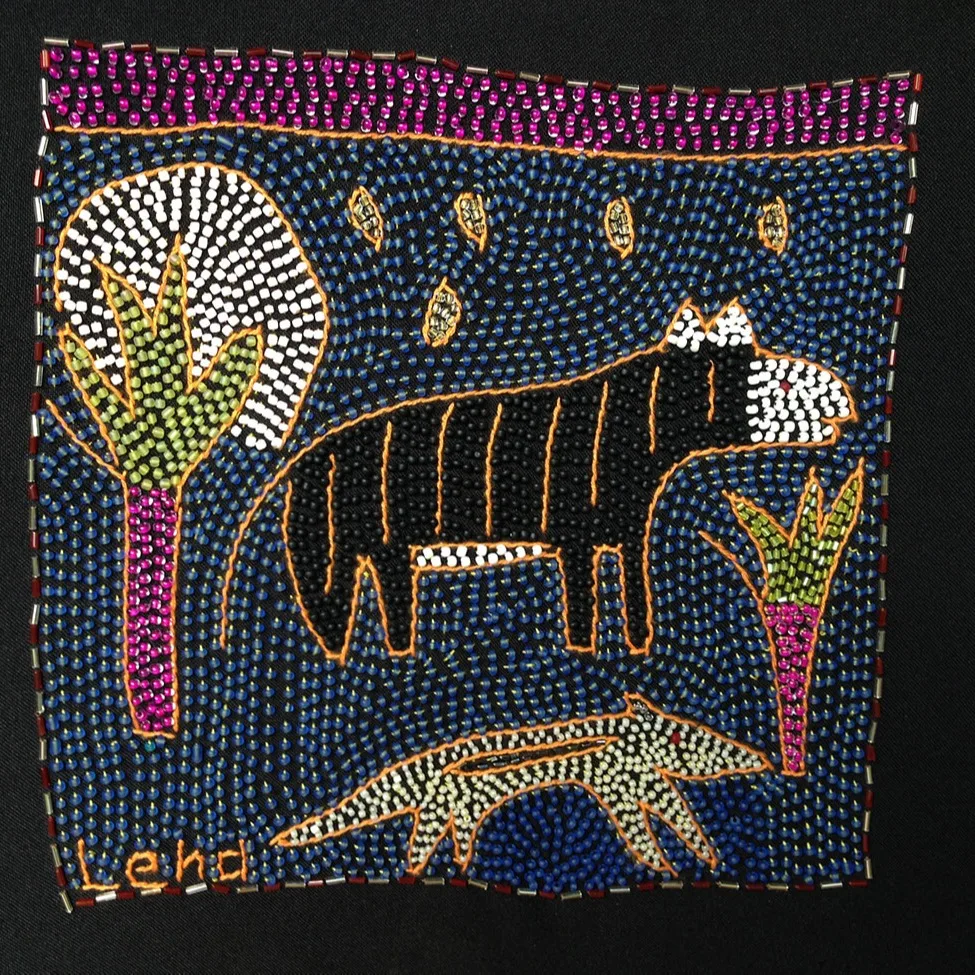

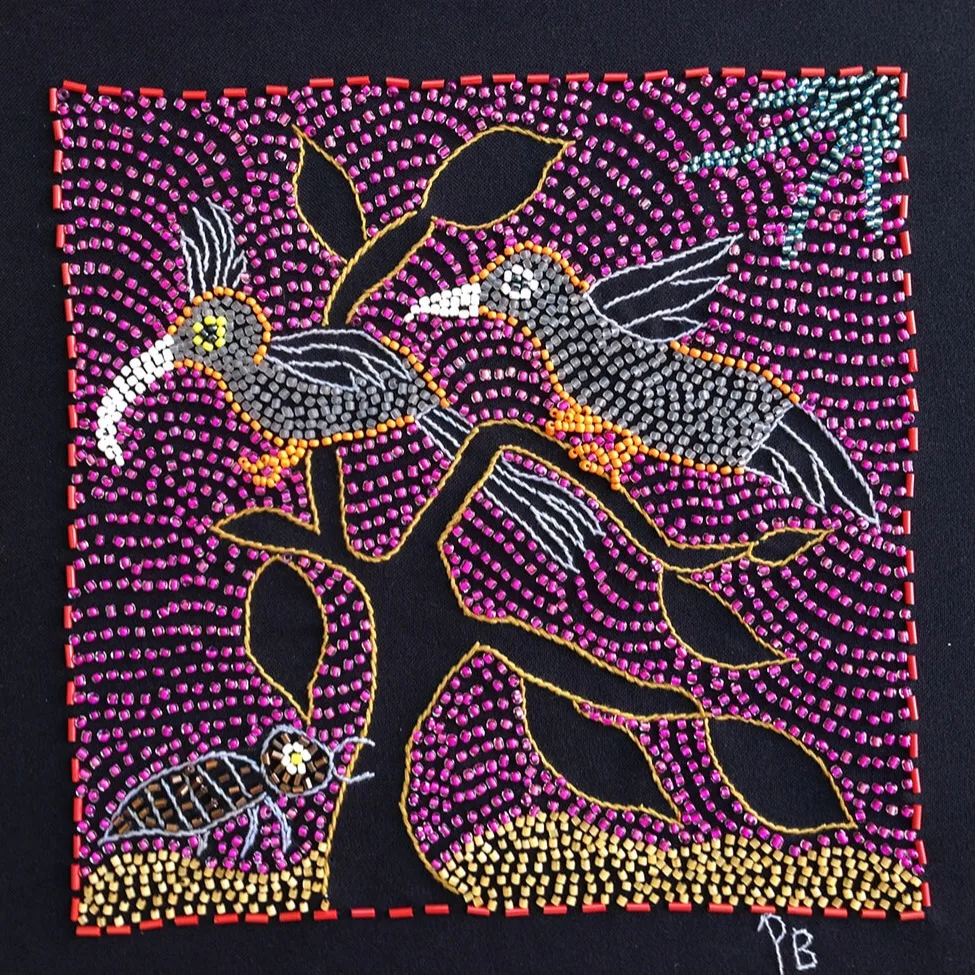

Omba helps cultivate local knowledge and skills, giving guidance on how to adapt these to a modern marketplace. “Glass beads have been traded among the San and others for centuries. Today the women still wear them and give them to family members, often to cement relationships,” says Karin. “It seemed like a natural progression to use glass beads in a new creative way. Now, women from Drimiopsis produce artworks depicting the plants they gather and scenes from their community using glass beads and embroidery on black cloth.”

These works are rooted in memories of the things these artists know intimately: the veld food they gather, including tubers and edible leaves, and the wild animals native to Namibia, such as elephants, rhinos, giraffes, zebras and guinea fowl. “Our role is not specifically to teach art but to provide a space for experimentation with art materials,” Karin explains, “to stimulate discussion around knowledge and culture, encourage story-telling and mark-making.”

Despite the painstaking slowness of embroidery, the resulting images have the ease and fluidity of drawing. The distortions of scale, perspective and color only add to their expressivity. There is a simplicity and directness to the forms, which are embroidered in a colorful array of beads to create an abstract all-over pattern. The unstudied abstraction of the embroideries recalls the qualities to which European modernists aspired, although this is not a point of reference the San artisans would understand.

We thought we were abandoned, but Omba has helped us stand on our feet.

Historically, ostrich eggshell beads were used to create decorative headbands with circular or triangular patterns. “Ostrich eggshell beads were made by our ancestors 72,000 years ago,” explains Monika Kaimanseb. “When we were young, we just thought of ostrich eggs as food. We didn’t know how to make these, but were taught by our elders that the shell could also be used for beads.” These beads, which the San call !go, are made in the same way as they were centuries ago: shaped by hand and then pierced through the middle by drawing a bow across a spinning drill.

Jan Gashe, one of the male artisans in Donkerbos who carves the beads, recently developed an innovative solar-powered method of doing this. Today, the traditional patterns are incorporated into modern jewelry or embroidered cloth designs that Karin describes as “rooted in culture but with a contemporary twist.” The women of Drimiopsis find enjoyment in making crafts that are connected with their heritage. “We put the jewelry on and ask each other if it is well-made. “ says Monika. “We take pride in creating something beautiful.”

The transition from a traditional nomadic lifestyle to one defined by land ownership and Western capitalism has been a rocky one, but there are many ways in which old customs are being revitalized. Josephine Stuurman, who joined Omba four years ago, describes adapting a pattern from a leather pouch that her ancestors would have used in hunter-gathering. “We take what our forefathers made and we put in on cloth so that our tradition and our culture does not die,” she says, “and we can share it with our children.”

In some cases, Omba helps to revive traditions that are in danger of being lost, restoring links between modern San communities and their own cultural heritage. Just one example is the Brandberg rock paintings in western Namibia, made between 2,000 to 4,000 years ago by ancestors of the San who travelled to the mountain in search of water during droughts. Even though thousands of international tourists visit these paintings each year, few from the Drimiopsis community had seen them until Karin brought pictures as a prompt for one of their workshops.

Josephine explains that the San’s marginalization has led to a reticence around sharing their culture. “Omba has shown us not to be shy,” she says, “that we should be proud of our culture and show it as San people – the first people on this earth.” As Mara poetically phrases it, “We are the roots of the first tree that was planted here. A tree without roots will not have life. Just as we are the roots, so Omba is the water that the tree needs to live and bear fruit. Omba sustains us so that we can grow fruit, so that we can bring food into our community.”

Over the past 12 years, Karin has seen Mara grow from a young schoolgirl into a mature woman and community leader. “I have seen the other women growing older, growing in confidence and I have seen them supporting their families. These women have very little formal education, but all groups have a bank account, they write out invoices, they have learned skills that equip them in their broader personal lives. That is how we envisage the work that we do – craft or art as a conduit for broader community development. It is a way of connecting, a way of building chains of trust and getting people to take ownership of their lives.”

Click here to learn more about the Omba Arts Trust and support their work.