Since 2022, Professor of Architecture Joshua Vermillion has been experimenting with AI tools within the design process, and encouraging his students to do the same. Of course, the technology can’t be relied upon to make structural decisions as to how buildings are constructed, but here writer Alyn Griffiths hears how Vermillion and his peers are beginning to discover how the tools could revolutionize the early stages of the design process, allowing architects to visualize extraordinary spaces—and communicate the ideas in their heads—in a heartbeat.

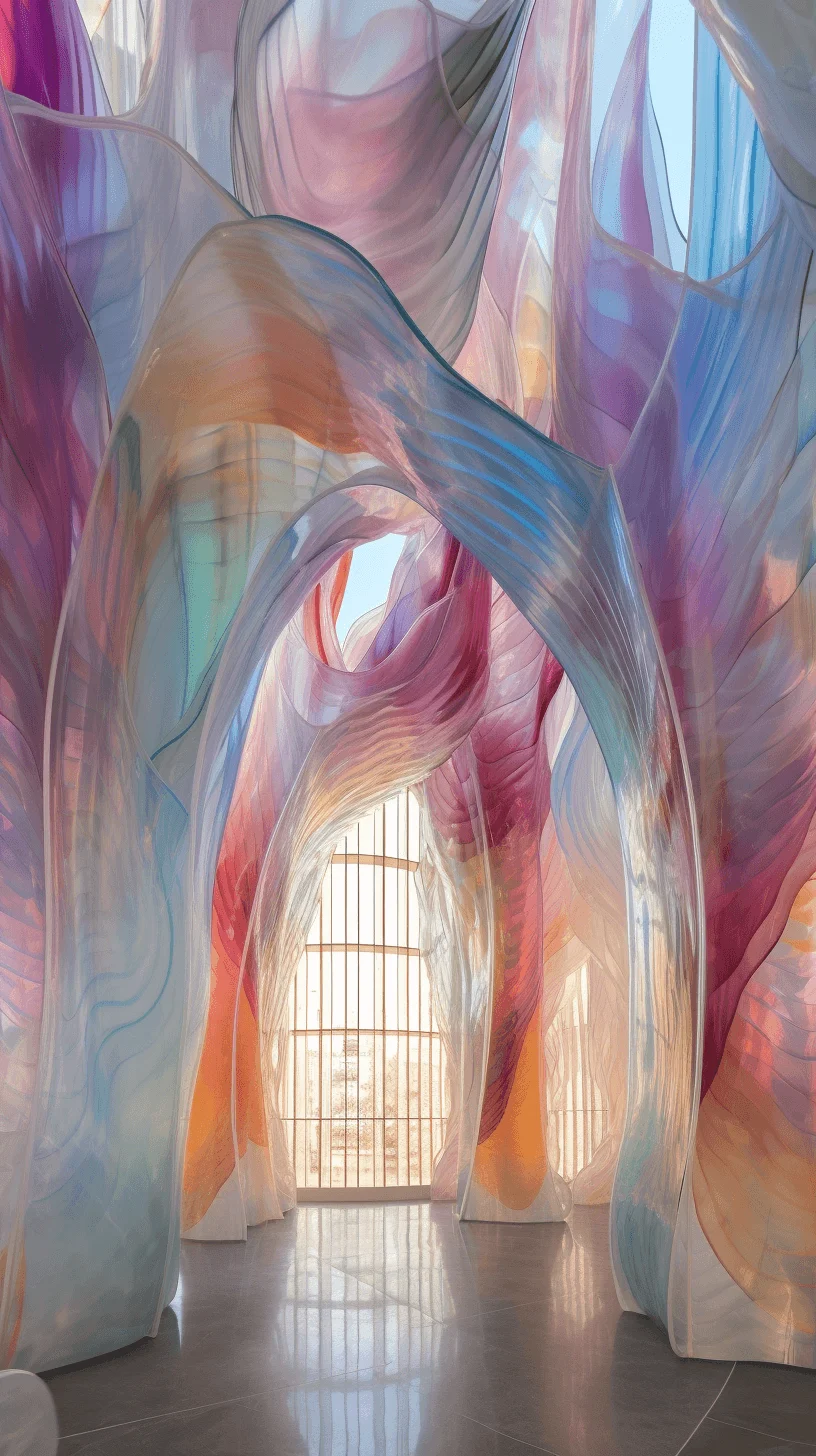

When he’s not busy inspiring students at his day job as Associate Professor of Architecture at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Joshua Vermillion enjoys using artificial intelligence software to generate uncanny, hyperrealistic environments that have become a big hit on social media. His digital artworks are often driven by a desire to achieve mind-bending effects using light, texture and translucency. They also represent a new way of interacting with computers that he feels could revolutionize his profession by augmenting the traditional design process.

“AI tools allow us to quickly simulate how a building might look or perform, or how it might feel to be inside or outside of it,” Vermillion points out. “It can generate atmospheric effects, material properties, reflections—things that once took days or weeks to achieve—in 60 seconds. It’s fantastic to be able to be so prolific at an early stage in the design process because it helps you to quickly prioritize things and understand what direction to follow.”

Vermillion began experimenting with artificial intelligence programs in the summer of 2022 after seeing examples of images his friends and fellow academics were producing using software such as Midjourney. His AI-generated artworks include depictions of cave-like rooms that appear to be made from eroded wax and gallery spaces filled with luminous latex bladders or intricately draped fabrics. Intrigued by the software’s ability to create detailed outcomes based on simple textual descriptions or image prompts, he set about trying to understand how this exciting new tool differs from more traditional ways of drawing or modeling ideas.

“What’s interesting is that you’re simply describing what you want and that’s a huge leap forward in terms of how humans and computers interact,” Vermillion explains. “Because of how it interprets the text and images you put in, a lot of the time you get what you asked for but not what you wanted, which I think is a really interesting dynamic. In that regard AI is more like a design partner than a slave to our demands. You can prompt it over and over again and have something resembling a conversation with it. I hate to personify it but I often find myself doing so without realizing.”

You often get what you asked for but not what you wanted. In that regard AI is more like a design partner than a slave to our demands.

Vermillion is already encouraging his students to utilise AI software in their projects and has been pleased to see how it encourages them to express their ideas through language. Each time they input text into the programme they’re rewarded seconds later with an image, which can then form the basis for iterative development or be used to communicate with their peers.

He says this could help streamline collaborative work by reducing time spent sketching or modelling concepts at an early stage in a project. “When you’re working in teams it’s often a lot easier if you can show people what you’re thinking rather than describing it,” he explains. “This tool really reduces that process of getting from an idea to a graphic output that everybody can see, understand and critique.”

It’s up to us now to experiment with this technology and challenge it, to see what it’s capable of doing.

Of course, there are limitations to what AI is capable of and some critics of the software have rightly pointed out that it could even be dangerous if computers are allowed to make important decisions about how buildings are designed and constructed. Vermillion agrees that AI is restricted by its lack of understanding of physics, climate, cultural systems, infrastructure and the many other considerations that influence real-life architecture projects. However, he believes that fears around AI’s impact are unwarranted as long as the software remains entirely under human control.

“Whenever a new technology emerges, people get scared that the machines are about to take over from humans,” he points out, “but right now AI still requires human input to generate anything meaningful. It is still the job of an architect to come up with ideas, to understand what’s possible and what’s not possible, and to curate the outputs the programme generates.”

Looking ahead, there appears to be little likelihood of AI software replacing architects anytime soon. However, as its popularity and capabilities expand, AI may begin to infiltrate our lives in new and unforeseen ways. Vermillion welcomes its potential ubiquity and the impact it could have as more people learn to live and work with the technology. He is keen to use the recognition achieved as a consequence of his artworks to promote greater awareness of AI and its future role in architecture, as well as in answering some of the existential questions confronting our species.

“We need to understand this potentially disruptive technology, so we can make informed decisions about how to use it for good instead of evil,” he says. “It’s up to us now to experiment with it and challenge it, to see what it’s capable of doing, how it can augment what we do and ultimately help us make better buildings, better cities and better environments.”