Scrapbooking is not a hobby you hear too much about these days. In a way, we still practice it, but in our Saved folder on Instagram, or in desktop folders of images and notes you can’t quite bring yourself to drag into the trash. But as a method of keeping, remembering, holding and documenting, “scrapbooking” by any means is a deeply personal, effective creative pastime. Here, writer Claire Marie Healy looks back at the more traditional art of scrapbooking, through the lens of Janis Joplin: Days & Summers: a new book of Janis’s diaries.

Did Susan Sontag scrapbook?

The answer to that question is almost certainly no. So why ask it? She definitely kept a diary, but even as a 14-year-old, the practice served to chronicle the fierce development of her literary passion and critical thought, qualities natural to a public intellectual-in-training (for a sense of her precociousness, just know that she visited Thomas Mann around this time, and found him wanting). In a favorite entry of mine, she circles around the central frustration of girlhood itself: the sensation of limits. “I come closer and closer to bursting this poor shell – I know it now – contemplation of infinity – the straining of mind (…) And knowing that I do not possess the outlet…”

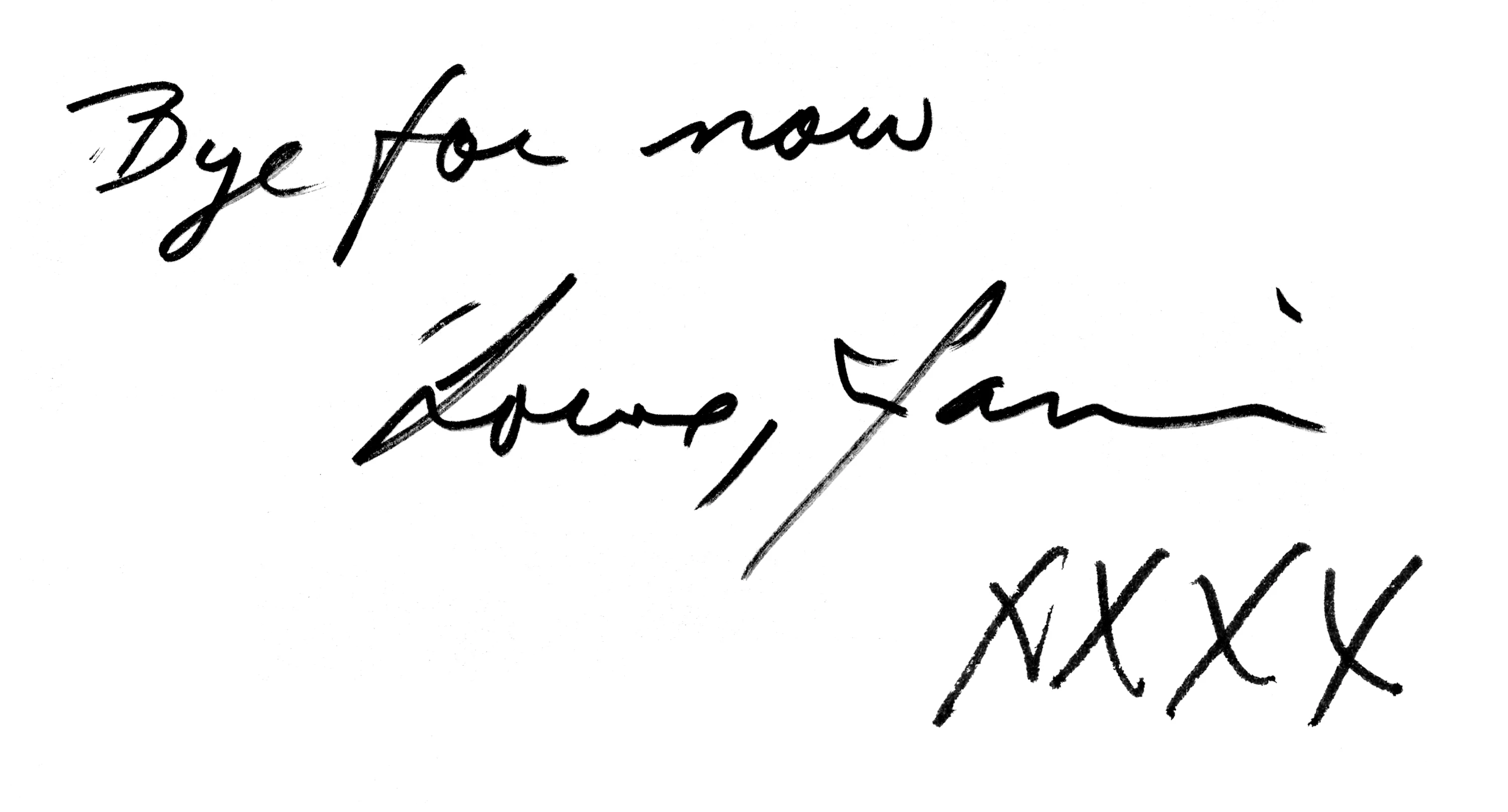

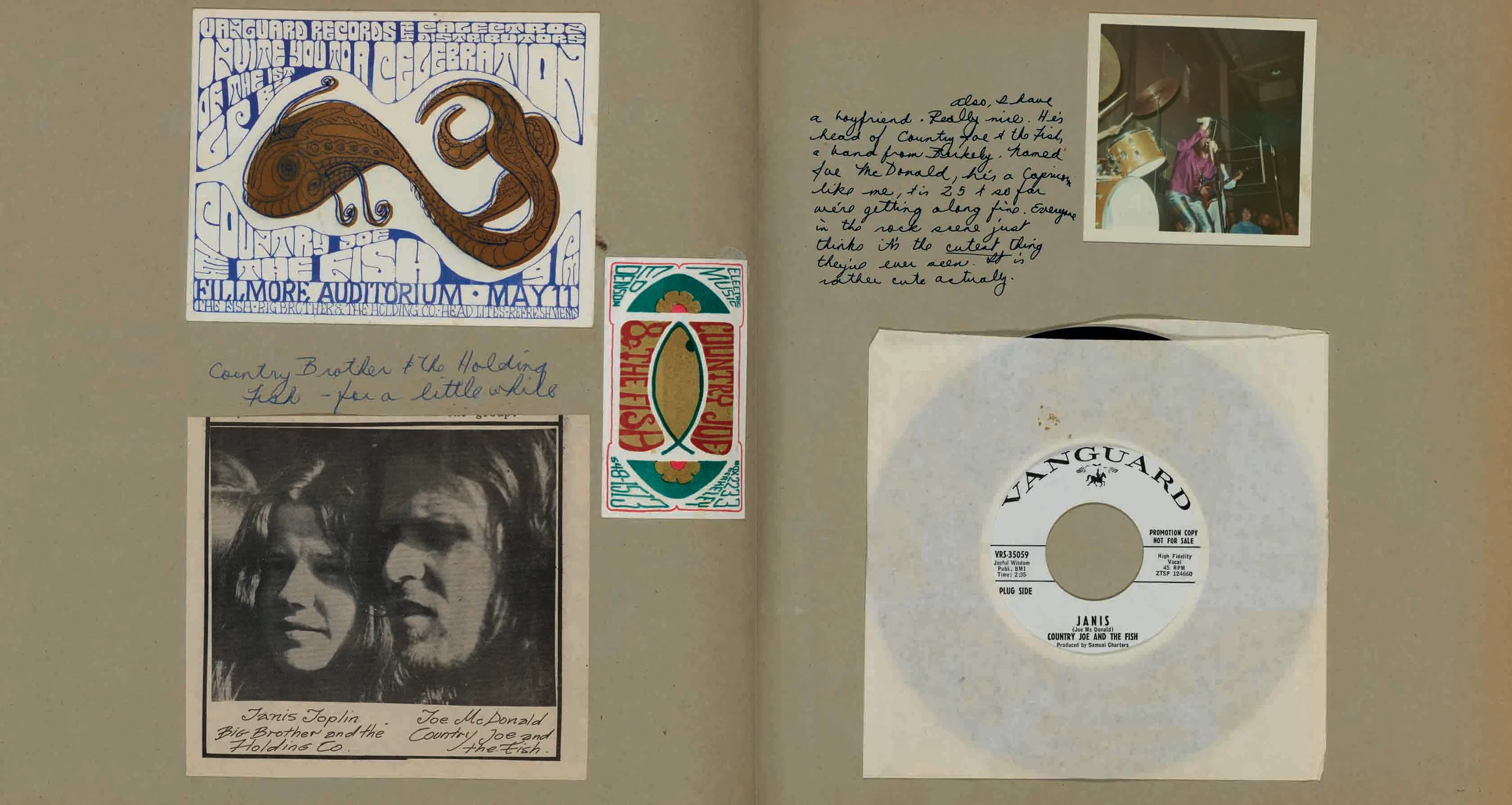

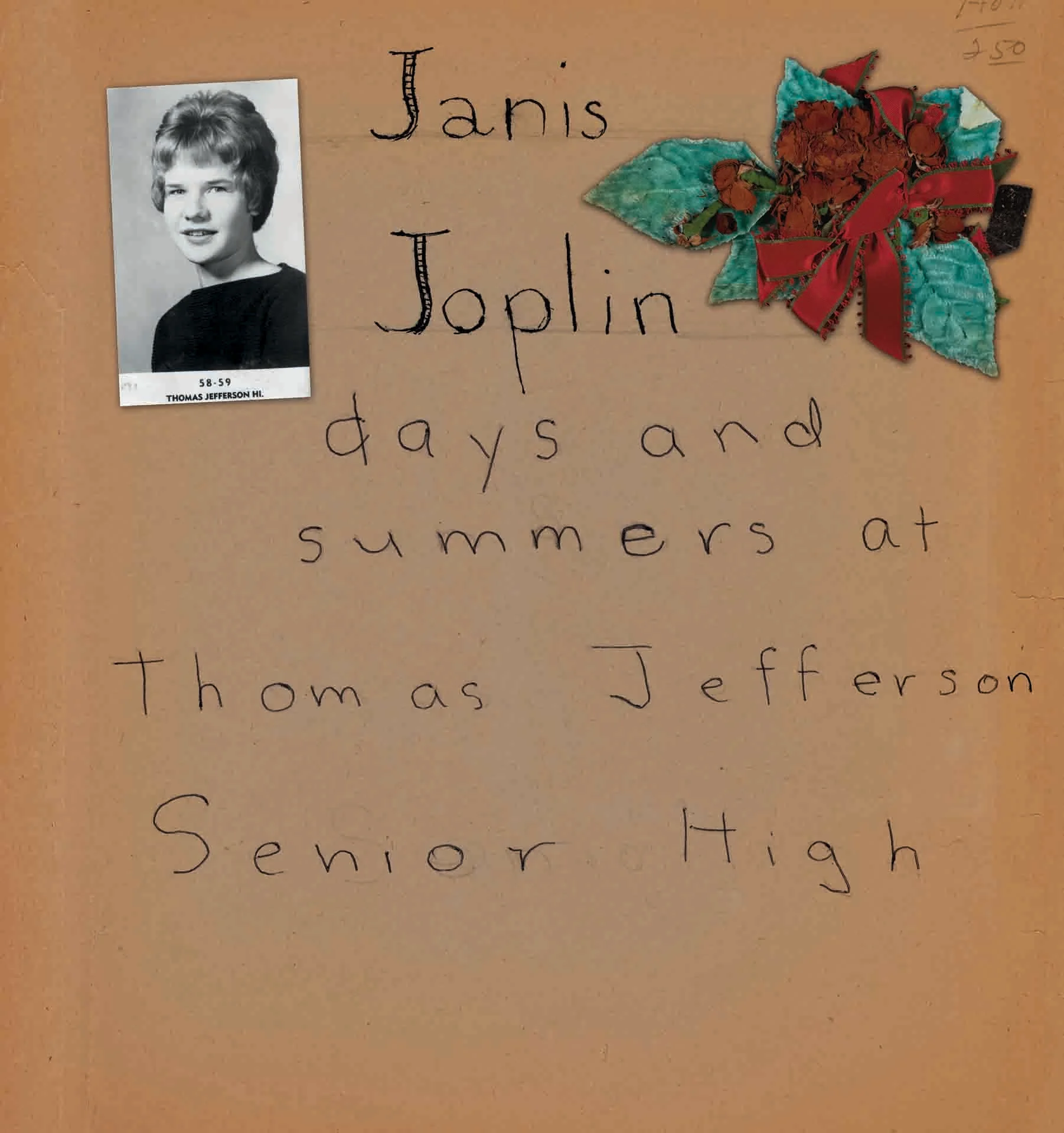

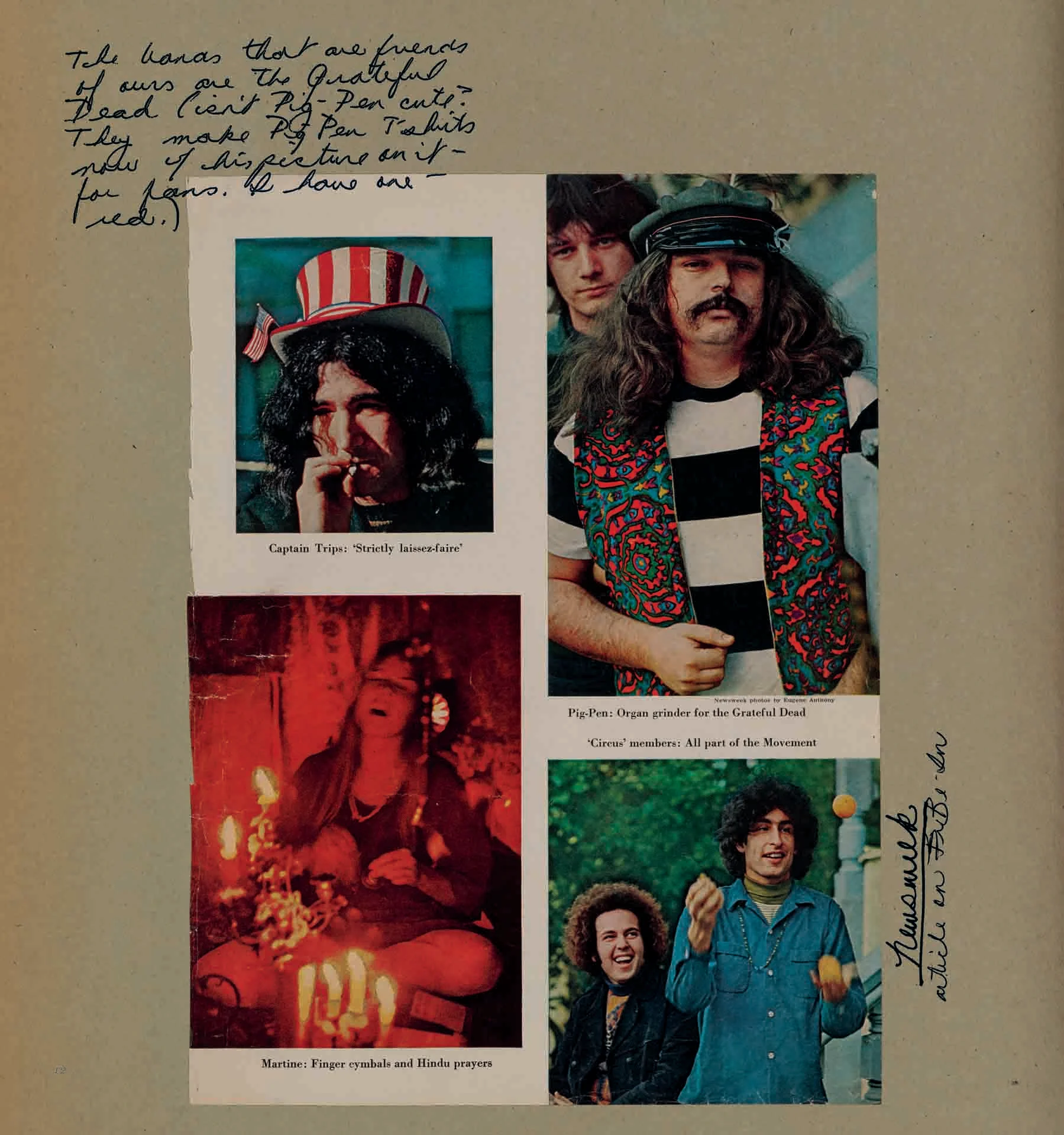

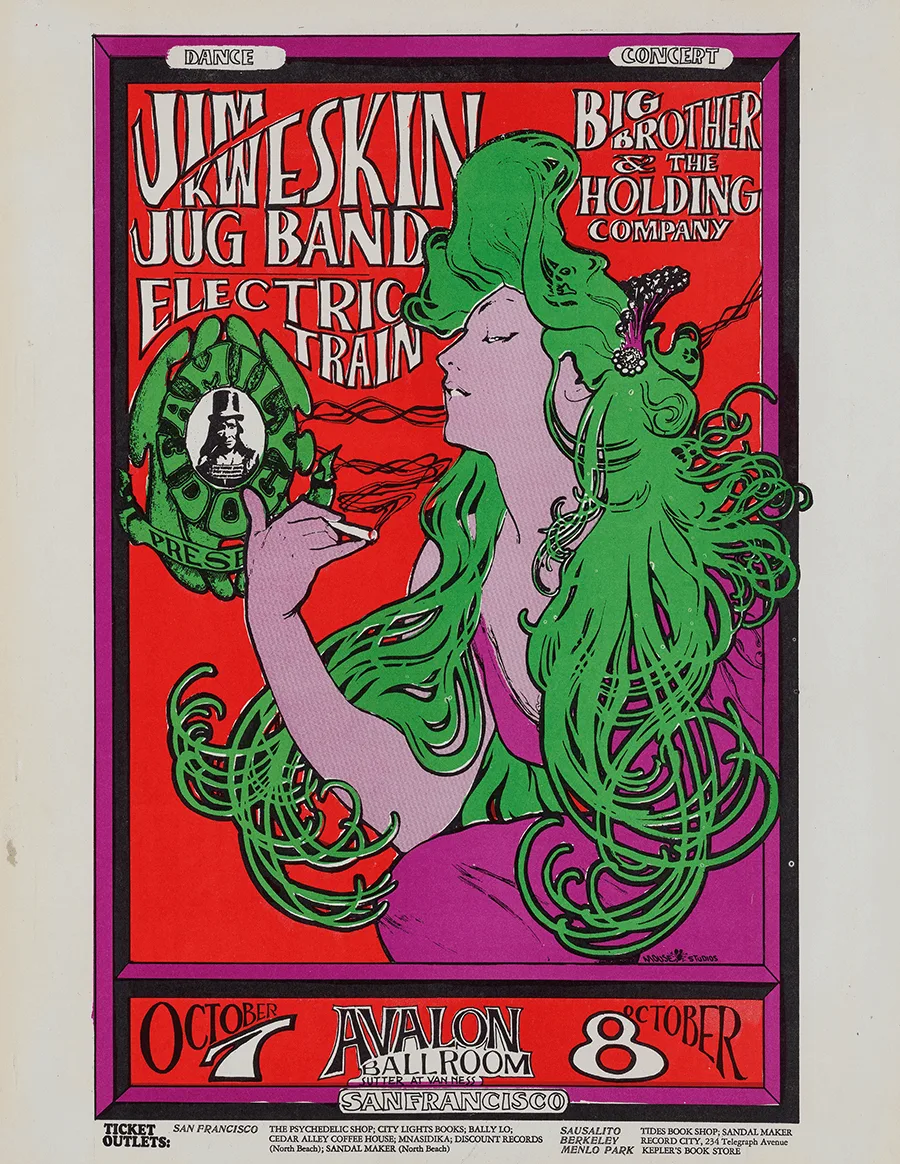

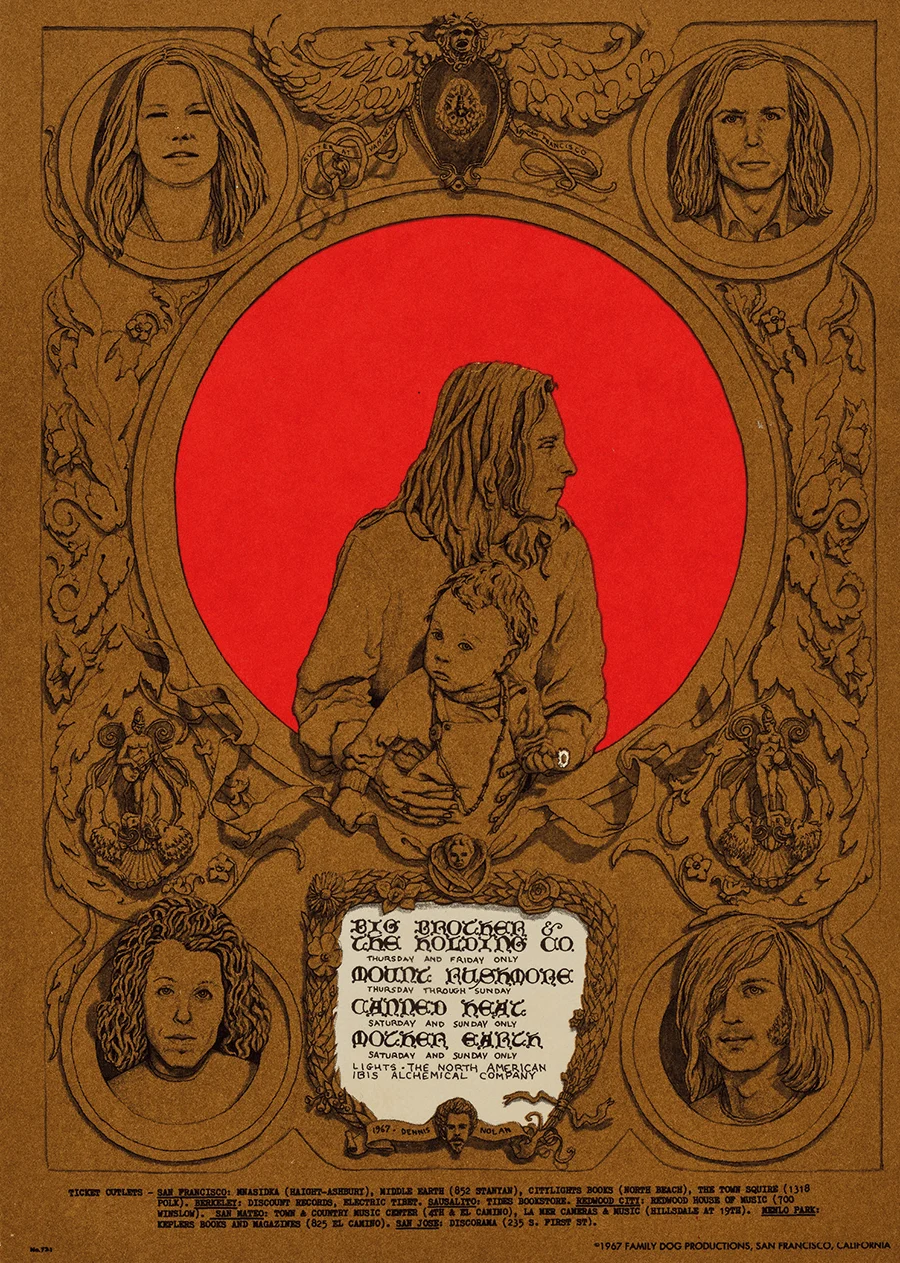

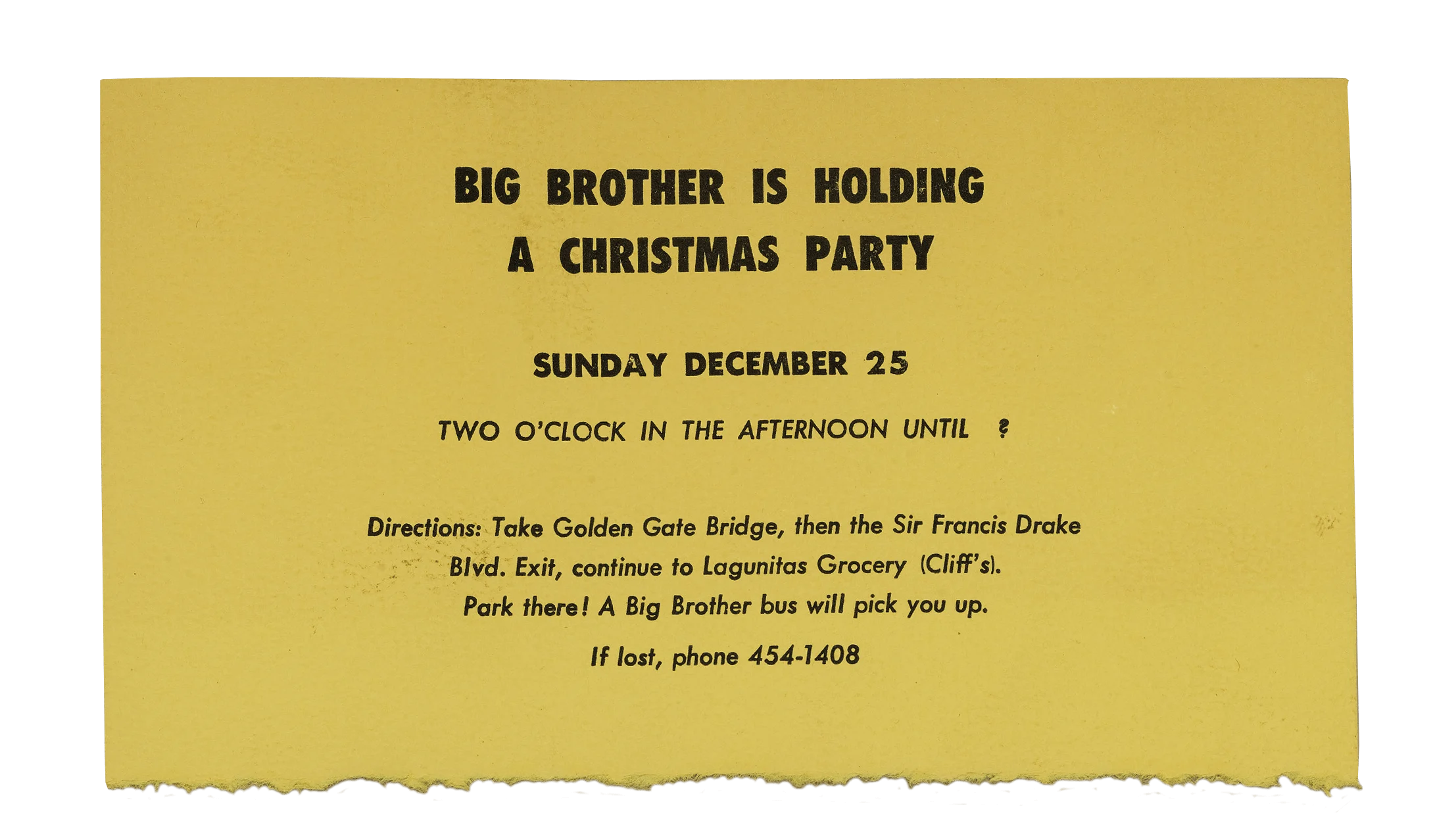

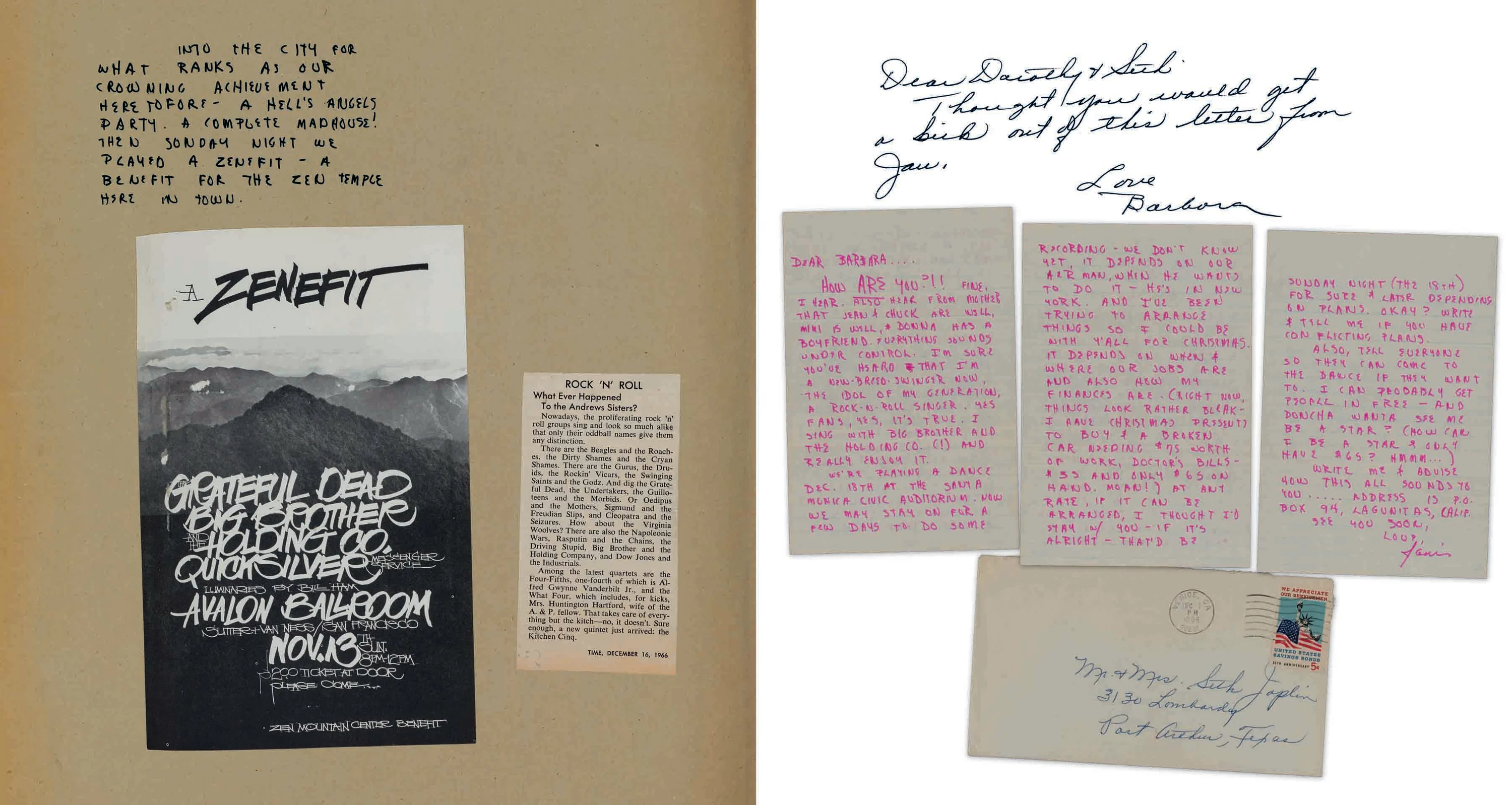

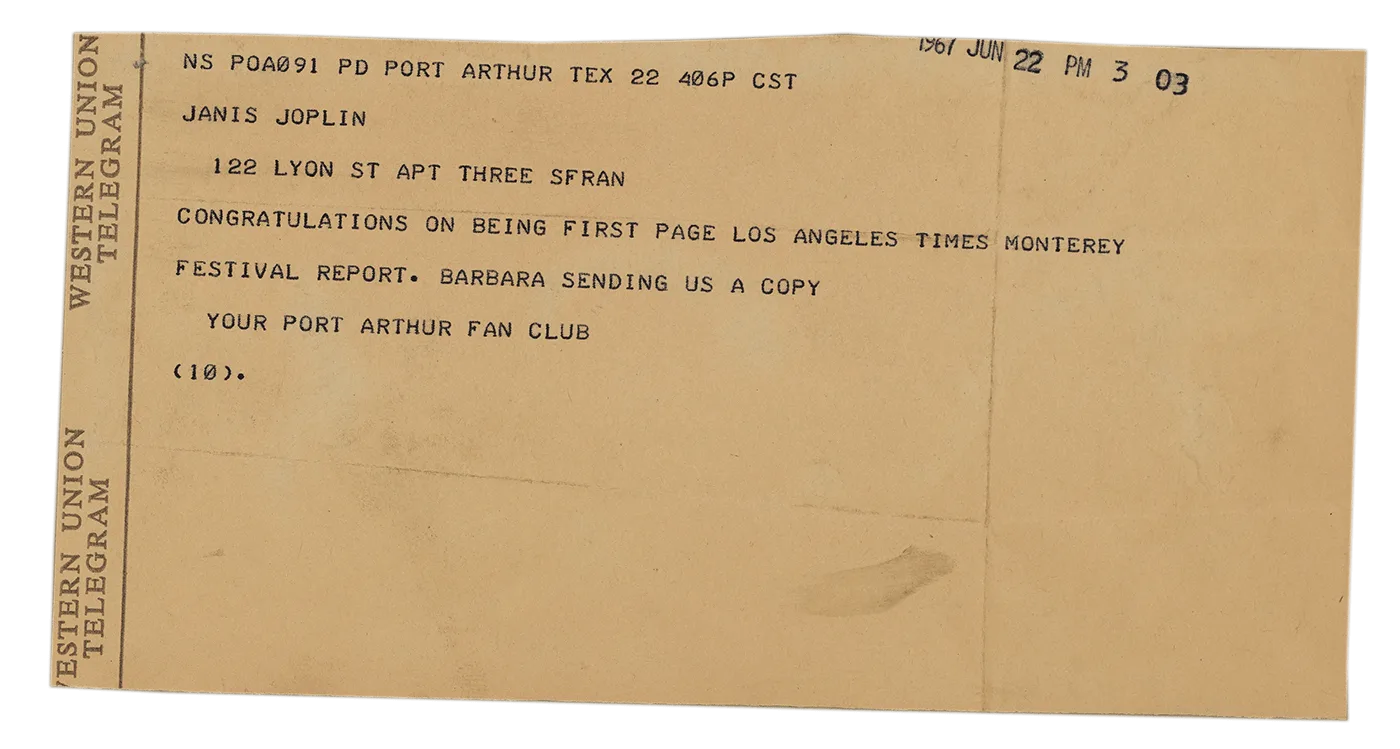

Scrapbooking feels like one way to contemplate infinity; certainly, an outlet to break one’s shell. And while we’re more used to the youthful diaries of creative people being published for later dissection, a new limited-edition tome dedicated to Janis Joplin bucks the trend. Titled Days & Summers – the same words she scrawled on the front cover of her very first scrapbook – it publishes, for the first time, the legendary singer’s personal scrapbooks, predominantly compiled between 1966-1968 as her star was rising with Big Brother and the Holding Company. Perhaps even more special, the book also contains one scrapbook that precedes Janis Joplin, rock goddess, by some years: pages from one she made at senior high, between 1956-1959.

For fans who hold the brief, blazing life of Janis close, Days & Summers is a special object. But it also crystallises what scrapbooking does for us that diaries cannot. To write a diary, even when we are young, is to think: what if someone were to read this? Like sucking in your stomach to fit through a narrow space, there’s a certain whittling down of your feelings to their most readable form that takes place with any journal-keeping.

The creative value of scrapbooks, alternatively, lies in the cut-and-paste, magpie-eyed process of their making – their scrappiness. Scrapbooking is a way to say: I was here – quite literally, in the case of gig flyers and ticket stubs – but also to say I am here, I’m assembling, my eyes and hands have built what you see. To scrapbook is to dream, and to desire, but it’s also to record those desires; an attempt to paste down experience, and sew it together, before it flies away. There’s a reason why so many teenage girls have turned to the form historically: as much as teenage girls are often criticised in the popular imagination for their flightiness, they are experts at preserving their selves.

The inherent value of scrapbooking lies in that careful communion with yourself.

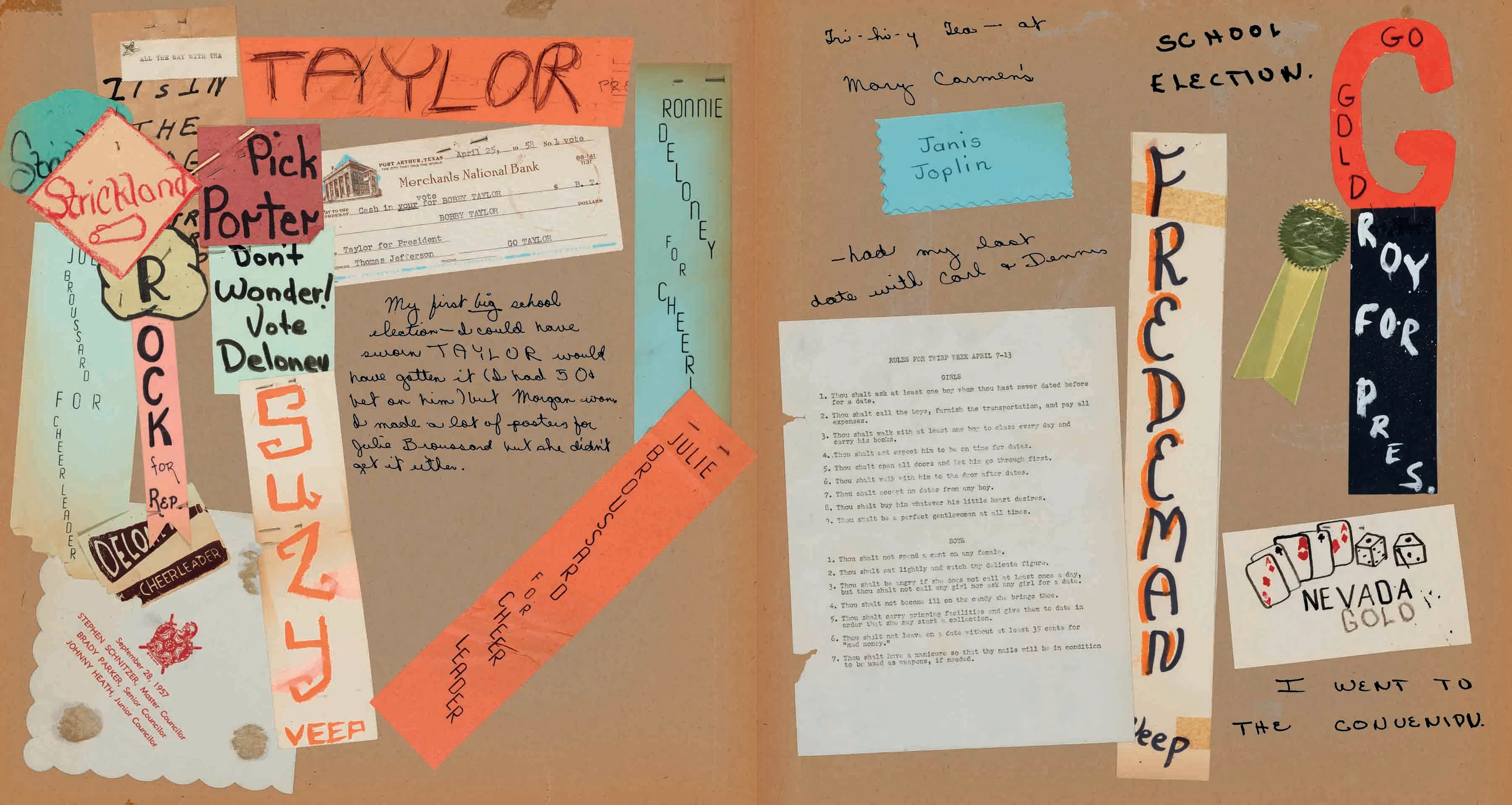

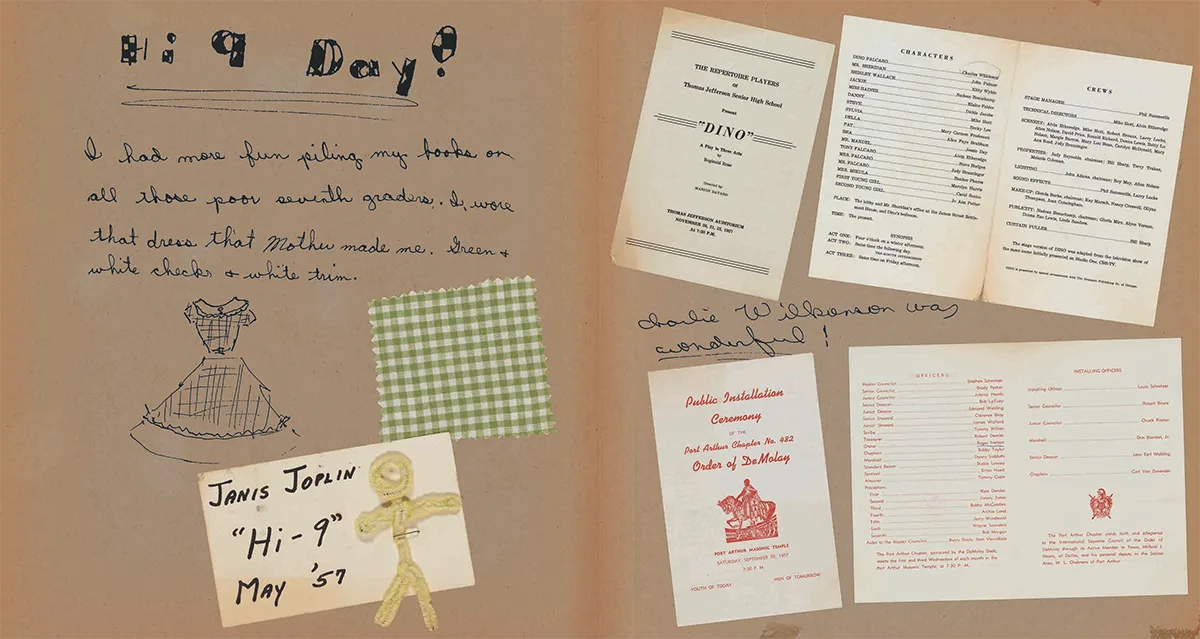

One of the most fascinating aspects of Days & Summers is seeing how the scrapbooks offered Janis an outlet for self-expression before she had really found her home in music. The fact that the musician was bullied for being an outsider in her Port Arthur Texas high school has been well-documented, but you wouldn’t necessarily be able to tell from her scrapbook pages. As reprinted in the book, Janis’ high school pages consist of a green and white gingham fabric swatch, in tribute to a dress her mother made her; playbills from school repertoire performances; a cut-out of a Valentine’s Day card featuring two cartoon hotdogs (Let’s be frank! I want YOU for my Valentine! – Joplin writes that she nearly fell off her chair when the teacher gave it to her); and newspaper clippings and various ephemera from basketball finals, cheerleader tryouts and the school election.

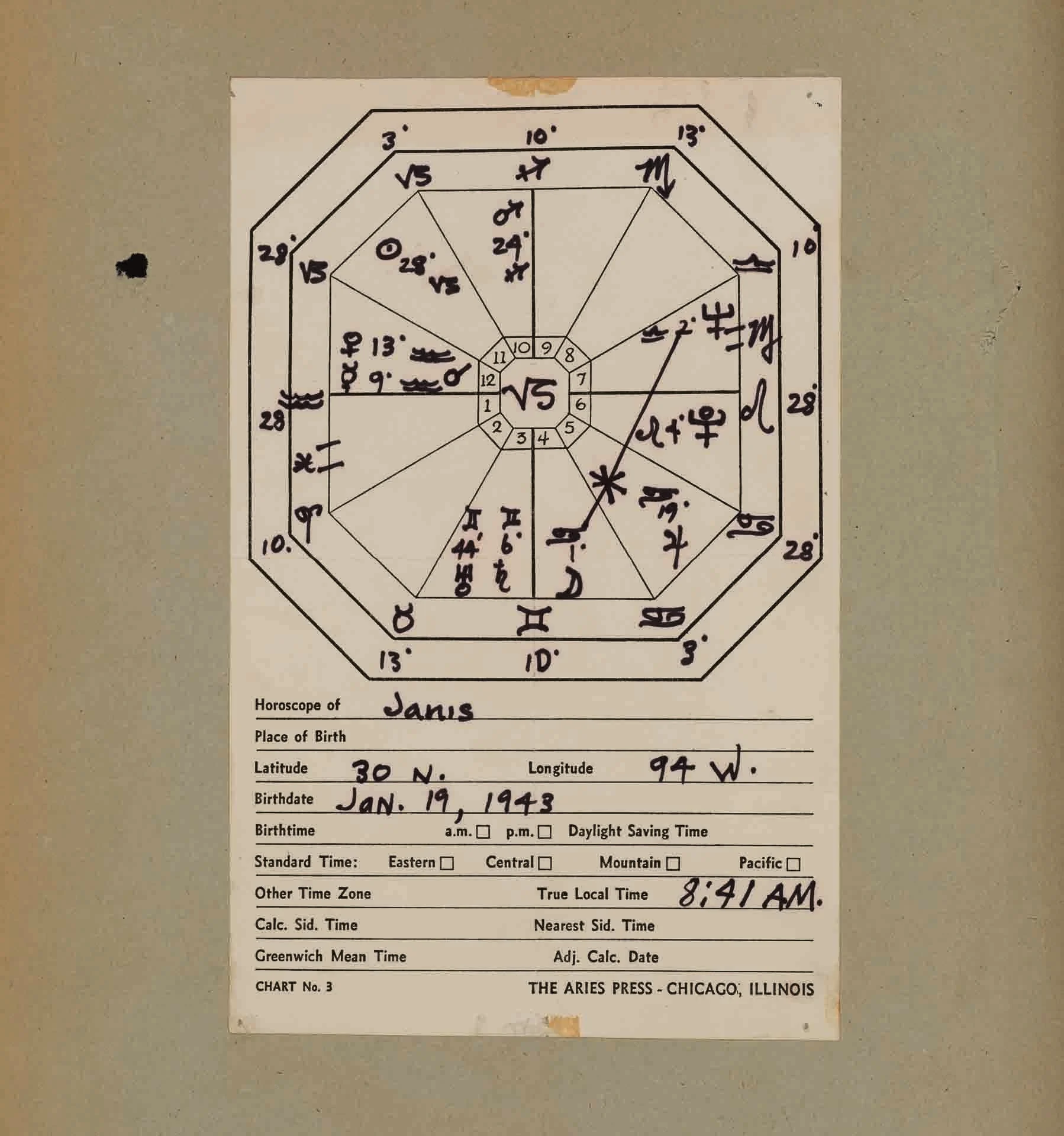

In a recent episode of You’re Wrong About on the Stepford Wives, podcasters Michael Hobbes and Sarah Marshall state that the problem with 1950s nostalgia is that it’s “nostalgia for a country that doesn’t exist;” an era of exaggerated societal and environmental ills, especially for women, that nonetheless we tend to look at through a rose-tinted lens. Joplin’s contemporary scrapbook pages, with their unrelenting optimism, feel a bit like that in the context of the knowledge of her struggles in school. Then again, if she did create her scrapbook as a space for positivity away from real life, that makes total sense, too. Besides, the high-school pages still show some of the same Janis spark that her fans adore, especially when read in a continuum with the later scrapbooks. Even well into her twenties, Janis tended to speak of boyfriends and crushes in a sweetly adolescent way – don’t we all? – pasting their portraits down amongst gig flyers and cut-outs of early reviews. “He’s a Capricorn like me,” she scrawls about one short-lived beau, “& is 25 & so far we’re getting along fine. Everyone in the rock scene just thinks it’s the cutest thing they’ve ever seen. It is rather cute actually”.

This sense of scrapbooking as an action of coming-of-age is mirrored by its approximation in the art world, where the form goes along with ideas of self-formation. In a 2014 exhibition at the ICA dedicated to artist’s scrapbooks from the likes of William S. Burroughs, Isa Genzken, and Leigh Ledare, the accompanying catalog defines scrapbooks as a visual record, and “a diary not just of thoughts, but of things,” but draws a distinction between the memory-storing purpose of a personal scrapbook and the purpose of a scrapbook for artists: “the artist’s scrapbook often trades in nascent ideas, both visual and textual, which may or may not grow into a more finished work. Such books allow an informal view into the process of thinking that goes before making; the collecting that comes before facture.” But is it as clean-cut as that? Surely the appeal of scrapbooking to teenagers is not purely sentimental, but equally nascent as it may be for artists. Whoever you are, scrapbooking can offer an organizing principle for self-actualisation: a record of coming-of-age as much about the process as what is actually stuck down on the page.

One trend in art publishing that combines both qualities – future memory-record, and spontaneous thought-process – sees the principles of scrapbooking applied to photographers’ work after the fact. For New York photographer Nick Sethi, whose photographic practice is embedded in the sights of his family’s home country of India, his 2018 book Khichdi (Kitchari) saw hundreds of photographs taken over 10 years tied together (literally – its colorful exposed spine is sewn-bound). Jumping page-to-page from screenshots of his Camera Roll to street photography, app-warped selfies of street kids, and interesting street signage, the result gives energetic form to the diversity of experience in the country. More recently, the LA-based photographer Deanna Templeton conversed more directly with her teenage self for a modern take on the photographic scrapbook. In What She Said, she combines scans of her pink-papered diary entries and saved concert flyers and ticket stubs from the ‘80s, alongside her contemporary street portraiture of adolescent girls. For Deanna, the process has represented a way to connect with – and maybe forgive – her troubled, younger self.

It’s an attempt to paste down experience, and sew it together, before it flies away.

Artists’ monographs aside, do young people actually scrapbook anymore? In the 2000s, the scrapbooking impulse transferred to the social media space, and most naturally to Tumblr, a site defined by its own scrapbook-like organizing principles: reblogs and notes, via which images pinball at rapid speed through the Tumblr-verse. Much like an image cut out from a magazine and transferred onto a page, every repost on Tumblr is itself an act of recontextualisation. But more than being architecturally resonant with teen girl scrapbooking, the site prompted an influential girlish aesthetic which seemed to hark back to the heyday of girlish scrapbooks – the kind you might find tucked in Molly Ringwald’s bookshelves in Pretty in Pink, or abandoned in the bedroom of the Lisbon Sisters in The Virgin Suicides. Rookie magazine, which can be understood on a Tumblr-adjacent timeline in terms of cultural impact (without the big tech backers) was also, in some sense, one giant scrapbook. The website, founded by publisher, actress and longtime scrapbooker Tavi Gevinson, was always fueled by the at-home creativity of a remarkably global teenage girl audience. This included a monthly collage competition, where readers could download a pack of different on-theme materials, create their own collage, and then send it back to be potentially published on-site. Still viewable on Rookie’s archive, these home-made dreamscapes are a testament to the site’s impact among its generation, with submissions from youths based anywhere from France to Singapore to Argentina and Mexico.

As the sad closure of Rookie, and downfall of Tumblr, attest to, things look a little different now in the internet landscape; specifically, any efforts to replicate the spontaneity of in-person creativity have given way to a world in which even scrapbooking is for sale. As reported in the New York Times last March, DIY Collage Kits are now being sold by influencers online, and plenty of teenagers are wholeheartedly buying into them. Naturally, for every single teenager buying influencer kits to collage onto their wall or into a book, there are hundreds still doing it themselves. But there’s no doubt that in 2021, the space into which young people extend their creativity has a dramatically different atmosphere to just a few years ago.

By removing an actual and imagined audience, it might be tempting to see a function like Instagram’s saved folder as more akin to a scrapbook (My recent “saves:” Cassie from Skins, a mid-century modern living room in LA, Maggie Cheung on a motorcycle). But even these tools, ostensibly serving our privately-held dreams of unreality, still exist within the confines and under the control of vast tech companies. As much as Google or Facebook want us to think otherwise, while we are using them for free, these apps will never provide the neutral, nor private, spaces of a blank scrapbook page.

Scrapbooking feels like one way to contemplate infinity.

Because when we talk about scrapbooking as a mode of documentation that has been potentially lost, you should know we’re talking about a kind of wider loss: of the idea that we might have ever dedicated ourselves to recording the things that we like, for our own eyes only. Not for an audience, nor money, nor posterity and never – to translate for the current moment – for clout. The inherent value of scrapbooking lies in that careful communion with yourself; or more accurately, that communion with your multiple selves. To scrapbook is to self-actualise through multiplicities; not, as Instagram would have young people prioritise, through a serene, minimalist, algorithmically-identifiable image. The point of scrapbooking is the inconsistencies, and what a certain combination of them gives birth to. A scrapbook doesn’t necessarily make sense, because it’s an imprint of ourselves in multiple formats, and we are always changing.

Maybe we can value and give space to scrapbooks as the teenage expression of one time, while acknowledging that teenagers right now might not express their selfhoods in the same way. When you acknowledge that a scrapbook is more a process of making – a mode of creative thinking – than an object to be shared, it comes closer to the activities of young people crafting multi-layered TikTok films, or teenage Hyperpop musicians when they start layering beats on SoundCloud. But when there’s always an audience in mind, the similarities end there; a scrapbook mentality might be in play, but the goalposts have moved.

Scrapbooks register differently when the maker is famous, or no longer with us – or both, as the case is with Janis Joplin’s. But the inherent joy of the artform lies in more than its status as a timestamp: really, the value lies in the fact that this individual spent time making, and processing, what was around them onto the page. One scrapbook that really hit home their value, for me, was Breonna Taylor’s, extracts from which were published on the New York Times in the wake of her murder at the hands of police last year. To look at the pages from her scrapbook, which are filled with color, flowers, hearts, and photographs of different milestones, is a powerful testament to not only who Breonna was – her tastes and interests – but of what scrapbooks offer to the individuals who make them: a space for everything that you are to yourself.

Janis Joplin: Days & Summer Collectors Edition is available to pre order from Genesis Publications.