In a public bathroom a young Irina Rozovsky once told a woman she was from Disney World. “I wanted to be as American as possible,” she says. In reality Irina moved with her family to the US from Russia when she was seven and spent years of her childhood trying to blend in.

“Photographically, I guess this has aligned me with others who have had to give up one home and find a new one, adapt, and then wonder what they left behind and who they have become," the New York-based photographer says. "I feel a tenderness for the experience of being displaced or disconnected from home, a kind of floating rootlessness."

Whether it’s returning again and again to neighboring Prospect Park for her series In Plain Air which she made while living in Brooklyn, or seeing a foreign land for the first time, Irina travels to make her bodies of work. Her first photo book One to Nothing was shot in Israel and her second, Island in my Mind, was made in Cuba.

Photographing a place shapes the way she sees it. “To be somewhere new is to need and want to photograph—it’s like my location device, a kind of GPS technique,” she says. “I tend to show up like a tourist and very quickly feel a strong, uncanny link, like I’ve been there before in a deep way.”

She’s drawn to picturing locations that are a bit chaotic, a little intense. “Usually there’s a complex history of struggle and perseverance and a kind of open vitality,” she says.

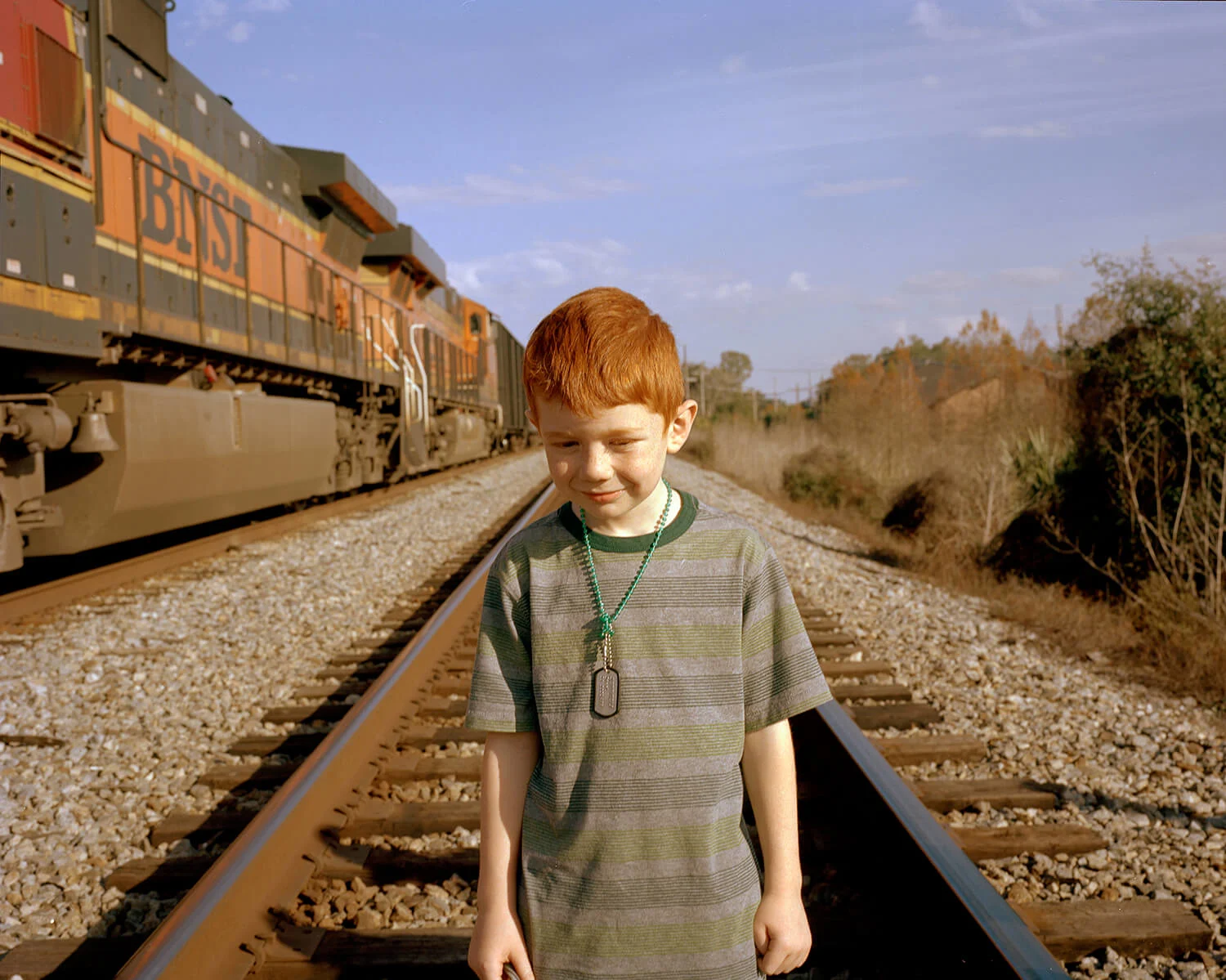

Through illuminating the everyday, Irina’s images become not so much a portrait of a place but a portrait of how she sees it. The larger socio-political tensions associated with them are only suggested through body language or visual metaphor. The message seems to be that even in politically contentious places, babies are born, trees grow, and the sun shines down on a discarded Coke can.

Driving around Macedonia shooting her series Mountain Black Heart, it pained her to see wildflowers growing among litter. On a one-woman clean-up crusade, she collected plastic bottles she liked and stashed them in the backseat of her rental car. For an impromptu still-life, she picked the flowers and arranged them in old colorful plastic water bottles in the sun on the roof of her car.

“I liked that these things were like road orphans,” she says. “Sea glass-colored plastic bottles in all sorts of incredible shapes, and flowers that no one had planted, that grew for themselves—these things arranged together breathing a new kind of fresh life.”

Beauty is an important tool that makes her images accessible; they can be enjoyed visually or emotionally without knowing more. The fact that they’re often shot in politically-fraught places, like Israel or Cuba, adds a deeper dimension.

Sometimes this added layer is caught by chance. It was only after shooting graffiti on a wall in Israel that Irina discovered it reads “God is Great” in Arabic and beside it a Hebrew reply asks “Which one?” In another photo she took, what she thought was just a parade of sheep walking on the highway, was a march on death row – their shepherd was guiding them to the slaughter house.

Even the saddest subject matter Irina captures in bright, warm sunlight or a brilliant flash cutting through the night. “I always want the photograph to vibrate with atmosphere,” she says. “Hot, bright places ought to burn on the page and the night has its own boundless dimensions. I want to let light and color stretch out in the frame and test the limits of our desire to believe in what we’re seeing.”

Irina’s uncommon imagery ignites an immediate desire to know whether the situations in her photographs were caught as they appear or if the scenes were composed. The answer lies in between.

“Generally, I try to insert myself into what’s already happening,” she says. “The camera is an excellent ticket in, but it always changes the dynamic. Sometimes I give a little direction but usually it’s chance and the subject’s incentive that makes the photograph work.”

Words by Alix-Rose Cowie.