Photographer Hannah Modigh’s family moved to Chennai, India, when she was three. During their four years there, the children were looked after by a woman named Sivagami. More than 30 years later, Modigh decided to return there to search for this woman, fuelled by the faint memories of their time together. She tells Marigold Warner how the resulting book, “Searching For Sivagami,” tells a story about the way memories change and evolve as we cling to them over time, and about the marks we leave on each other’s lives.

Between the ages of three and seven, Swedish photographer Hannah Modigh was raised in Chennai, a city in India's Tamil Nadu region. Her parents hired a local woman to look after the kids while they were at work—her father at an NGO, and her mother as an artist. For four years, their helper Sivagami became part of the family. She looked after the children every day—braiding their hair, walking them to school, feeding them—and in turn, the family looked after her too.

Smells are so linked with memory… when I hugged her, the smell of her skin really brought me back.

When the Modighs eventually moved back to Sweden, Sivagami cried. At the time, Modigh interpreted this as tears of loss. But later in life, as an adult with her own children and responsibilities, she wondered whether Sivagami was worried about her own future without a job and stable income.

Three decades passed until around 2018, when Modigh was working on a photography project about her family. “I started thinking about Sivagami, and how maybe I should just look her up. Just try at least, even if I don’t find her,” she says. The following year, Modigh travelled to Chennai. She only had Sivagami’s first name, which is ”very common in the south of India,” she says, “It’s like walking around and asking for Hannah in Sweden. I felt like I was never going to find her.”

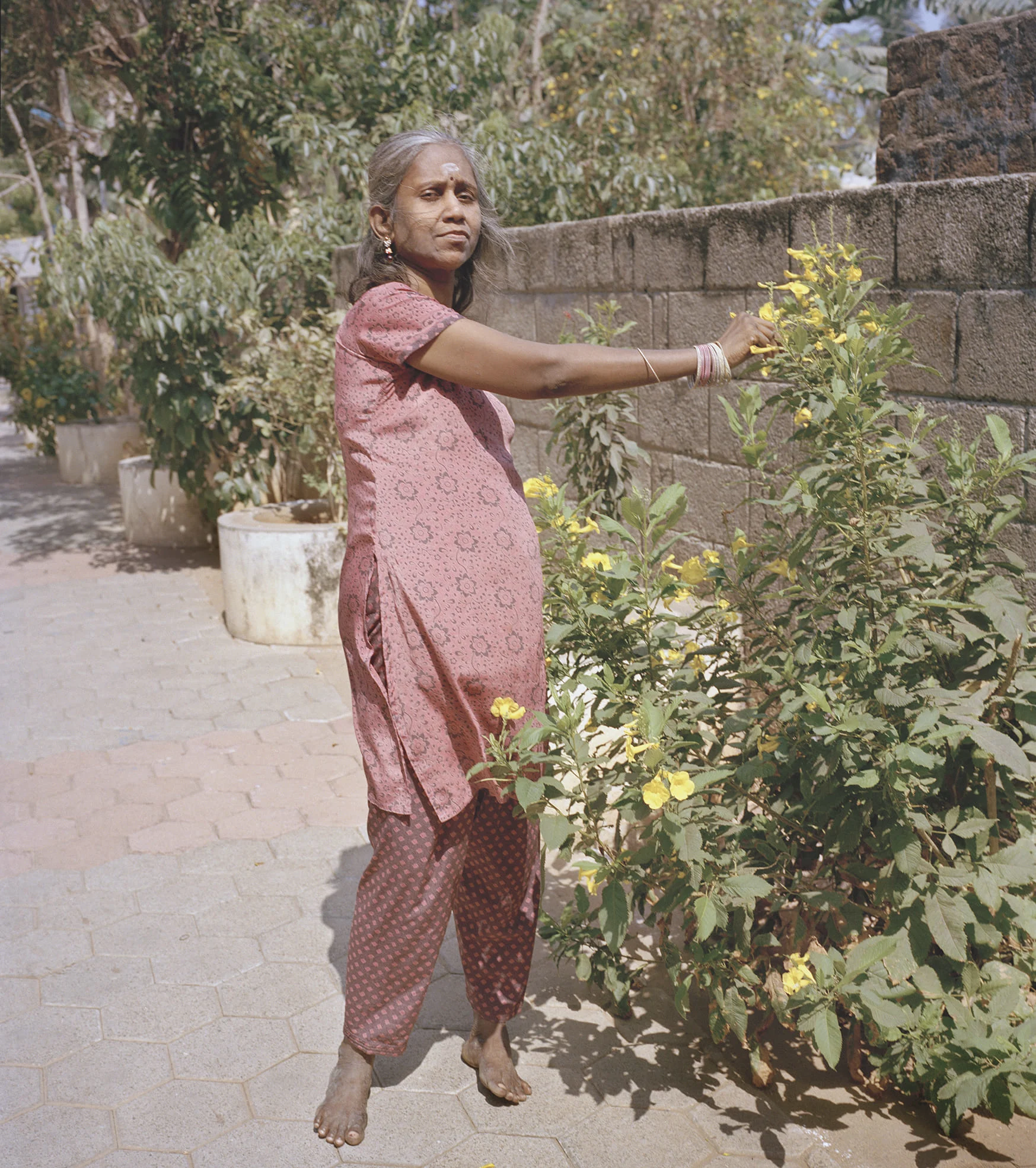

Nonetheless, Modigh was committed to the search. She drifted through beaches and temples, retracing the streets they once walked together and stopping to photograph every woman she encountered along the way. “It was almost like they were illustrating the search for a relationship,” she says. After two weeks, Modigh had almost given up—until, on the very last day, she asked a stranger on the street if he knew her. And he did.

When she found Sivagami, sitting crosslegged in her living room, sensorial memories from 30 years ago came rushing back. “Smells are so linked with memory,” says Modigh. “She looked the same in many ways, just so much older. When I was kid I used to sit on her lap, so I remember her as this big person. In reality, she was very small. But when I hugged her, the smell of her skin really brought me back.”

Photography, for me, is a lot about trying to find or heal something that you don’t really understand.

This journey is now the subject of Modigh’s latest photobook, “Searching for Sivagami.” It is an accordion book, unfolding to present a sequence of two chapters—one on each side. The first is about searching, based largely on fragmented, often unreliable childhood memories. We see the backs of women's bodies, and photographs that nod to things left behind: a pile of hair clips, for example, or chalk handprints and a sea of empty shoes. “I’m almost frantic in my search, walking behind all the women, but not really getting any contact,” she reflects. “Some of the memories from when you were a kid, they don’t feel real. And so I kept wondering, was she really a person, or is it this fantasy?”

The second chapter takes place after finding Sivagami. The release she felt is echoed in the images. “The relationship between the people I photographed became more intimate, happy and free,” she says. Throughout both chapters are handwritten pencil scrawlings, describing memories, or annotating photographs from the past. “The whole book is about memory,” says Modigh. “I was so young, so I never talked to anyone about mine, but I replayed them for so long in my head, because I didn’t want to lose them. And they’ve stuck with me all of these years.”

What’s interesting about these photographs is that they are all based on memory in some way, because Modigh ended up having to re-shoot all the images. After finding Sivagami, the photographer had to rush back to Europe to attend an event in Paris. She stopped off in Sweden on the way to drop off her film—almost 200 rolls. As she was boarding her flight to Paris, the developer called and told her the rolls of film were entirely blank. “It was heartbreaking,” Modigh says. “It was almost like I found her, and then I lost her again.”

Modigh knew she had to go back to India, and this time she took her mother and sister. “Sivagami meant so much to all of us,” says Modigh, “but we didn’t know if we meant anything to her. Were we just another job on the road, or was the connection real?” When they reunited, Sivagami was wearing a silver ribbon around her neck, holding a small key for a box filled with precious trinkets. Inside was a worn photograph of Sivagami holding Modigh and her little sister. “In that moment I knew that we were important to her too, and it made me feel so much more free,” says Modigh.

Sadly, just one month after their reunion, Sivagami passed away. “I was lucky in a way, that we got to meet each other again,” Modigh reflects. There are only two photos of Sivagami in the book, sequenced side-by-side. Almost identical, she is sitting in her front room, just as Modigh had found her. “When you look through the book, you don’t really know who she is. It’s almost like the viewer is searching for her too,” she reflects.

For Modigh, the photographic process is in itself a search too. Her book asks many questions: Do memories live in the mind, the body or the landscape? Or perhaps they are like ghosts, lurking in alleyways, lost in the ocean, or trapped in the dark crevices of our unconscious. Like all good stories, Modigh’s narrative urges us to dig deeper into ourselves. To search for the memories, dreams and fantasies that live within all of us, waiting to be unearthed. “Photography for me,” she says, “is a lot about trying to find or heal something that you don’t really understand.”