The danger when it comes to discussing graphic design – as is the case with many creative disciplines – is that it gets siloed. Experts pore over details and reference and review it from a very inward-looking perspective. For London-based publishing house GraphicDesign&, this is a tendency each of its books is designed to tackle.

As its name suggests the studio of Lucienne Roberts and Rebecca Wright look at graphic design in relation to other social and cultural phenomena – whether it’s literature, maths, social science, or in the case of its new book, religion.

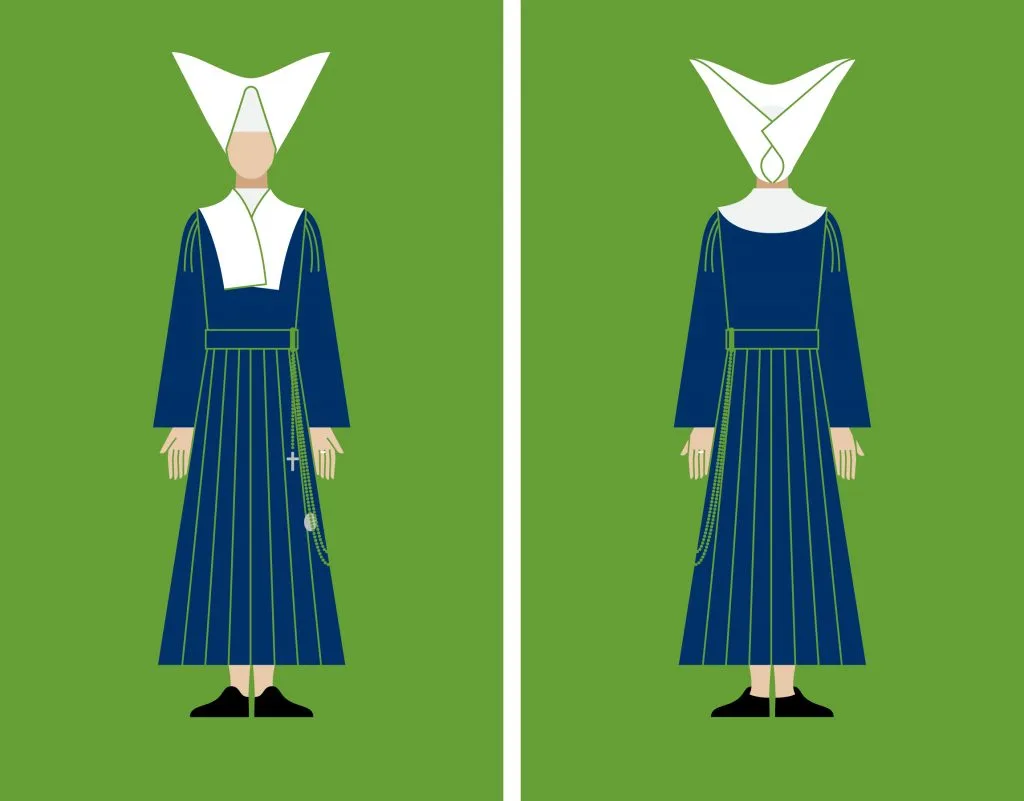

Looking Good is a marvellously strange little tome, a visual guide to the costumes worn by 40 communities of nuns around the world. Illustrated by Ryan Todd, the book started off as an in-joke but became a seriously good study of these intriguing fashions. Aptly, the book is dedicated to Sister Mary Corita Kent, a nun whose graphic design work has been heralded as some of the 20th Century’s defining visuals.

We spoke to GD& about the book, and what it was like immersing themselves in the world of nuns…

First things first – why on earth did you decide to make a book about this?!

We have always wanted GD& to tackle projects that might be too eccentric, too risky or too niche to appeal to a more mainstream publisher and in one of our earliest discussions the subject of religion came up.

We discovered that we each had childhood experience of the church and so shared a perhaps unfashionable curiosity about its rituals and regalia. We discussed a variety of interesting overlaps between design and religion (some designers see their practice as akin to a calling after all), but it was the simplicity and symbolism of religious dress that fired our imagination most particularly.

Initially we joked about creating a spotter’s guide to the nun’s habit – as a former convent girl Lucie thought it might be useful while holidaying in a variety of churchy destinations!

But, as we researched our idea more fully, a far more GD& idea began to take shape. Religious communities have been using color, form and symbol to communicate their identity for hundreds of years, making the habit a form of visual code.

We concluded that graphic design and illustration were uniquely placed to make this tangible to a wide audience and that this should be the remit of our book. This isn’t a religious book, but it’s a book that looks with interest and affection at the garb of religious women. It’s definitely our quirkiest project so far, which is part of what we love about it.

The GD& mantra is to “explore the symbiotic nature of graphic design practice” – how does this book fit into that wider vision?

Graphic design always exists in relation to another subject, and yet design itself is often little thought about outside of the industry. As such, all GD& projects are intended to explore what graphic design can add to another subject area, and how that relationship can be mutually beneficial.

For Looking Good, we worked with Veronica Bennett, a theology graduate. She quickly discovered that there isn’t any single repository for information about the habit; it’s spread across blogs and websites, and in the hands and history of individual orders.

On one level the book is a synthesis of this information, but because it’s a GD& book, it emphasises sign and symbolism and (we hope) reaches to an audience beyond nun obsessives. It’s also an opportunity to talk to a very different group of people about graphic design.

Were you surprised by the range of different costumes you encountered when you started researching this? How do you see that relationship between “uniformity and variety” you discuss in the book?

It was interesting how orders can be distinguished by subtle differences (the number of knots on a rope, a particular crucifix) or by a completely unique outfit (a ruby-studded crown, an entirely red habit). There were some habits we had never seen before, and in fact some that are never seen. The pink habit of the Holy Spirit Adoration Sisters, for example, is only worn inside cloisters: if the nuns leave the convent grounds they don a plain grey habit.

Flicking through the book at speed is a great way to get a visual sense of the relationship between uniformity and variety: hems go up and down; bare feet make way for shoes and sandals; veils in white, grey, black, violet and blue are long and voluminous then short and pinned back.

We see crosses and crucifixes, sewn or worn on chains; belts and girdles; knotted cords and rosary beads. Cloaks and cardies and cucullas are all here and yet each image clearly depicts the same thing – the habit, this highly recognizable uniform that can withstand all manner of subtle variation while retaining its essential character.

What about Ryan’s style suited this project so much?

We wanted to convey the feel of information design (Otto and Marie Neurath’s celebrated Isotype system was one of our references), but without losing the essentially human nature of the stories we were telling. Ryan’s illustration style is restrained, elegant, but also warm, so we thought he would be a perfect fit.

Ryan approached the project with great enthusiasm; he understood perfectly the intention to develop a simplified “kit of parts,” which could nonetheless capture what was unique in each habit. He worked closely with Veronica to make sure we didn’t lose anything important when building the illustrations. We’re delighted with how the final illustrations have turned out – the nuns’ hands are particularly exquisite.

How do you see the role of nuns in our cultural consciousness, and how do you see that changing given the way religion and gender politics are changing?

From Julie Andrews in The Sound of Music to Mother Teresa (now St Teresa of Calcutta), nuns occupy a special place in popular consciousness as figures of fondness, fun, strictness, purity and grace.

The reality of nuns’ role in history is more complex than this, but as Looking Good is specifically a history of the habit, rather than a book about the Catholic faith more widely, it doesn’t look deeply into the ambiguous histories of religious life.

However, it is a window onto religious identity – specifically visual identity – that feels particularly relevant when conversations about religious dress are in the mainstream news. There are two “trends” in habits that we identified in our research.

The first is modernising. After Vatican II (a religious council held in the early 1960s) many orders have amended their habit to better suit their activities, adopting something closer to a contemporary uniform, or even everyday dress. The second is a return to tradition. Many of the newer orders have adopted a full habit, with voluminous veils and cloaks, emphasizing their visual impact as they go about their work.

Both of these trends seem to point to a desire for identity and definition, perhaps as Veronica observed, “as a reaction to the loss of a visible presence of religious life in the secular world.”

What is the single strangest thing you learned putting this book together?

We learned so much, but what really stood out – apart from the endlessly fascinating habits, of course – were the personal stories (some of which didn’t make it to the final book).

Among these were the lumberjack nun, who took early health insurance to Minnesotan loggers in the late 19th century; the stargazer nuns, who were recruited by the Vatican to map the night sky; Mother Angelica, who started the Eternal Word Television Network out of her convent’s garage; and Little Sister of Jesus founder Magdeleine Hutin, who travelled behind the Iron Curtain in her van the Shooting Star (specially designed to accommodate four sisters and hide the Blessed Sacrament).