Culture is no longer a one-way street. The internet has opened up many ways for people to interact with the things they love. From Sherlock to Stranger Things, Harry Potter to Harry Styles, fans are increasingly creative as they build on the phenomena they identify with. Hayley Campbell looks at fan art, why people create it and how the very nature of fandom is changing.

How do you say thank you to someone who made something you love?

You can hang the poster on your wall, you can pay to see the film seven times in the cinema even though you can’t afford it, you can wear the T-shirt until it falls apart. But it feels incomplete, it’s not a message – it’s just something you did.

Art is a dialogue but sometimes it can feel one-sided; someone else is the creator and you are a passive consumer. Sometimes, something moves you to the point where you want to be part of it, however tangential that may be.

Anyone can wear the T-shirts, buy the posters, sit in that cinema time and time again. Fandom is a level above that. Being a fan is an identity – it’s an act of self-definition. It’s another label on your Tumblr, sure, but it’s also a way of interacting with the world through the prism of this thing that you love.

In the early days of the internet, fans from across the globe found each other using slow dial-up modems, Netscape and AOL, Usenet lists, Yahoo! groups, and LiveJournal. They swapped fan-fiction and invented storylines, exploring narrative arcs merely hinted at in their favorite television shows, drawing them out to their logical conclusions.

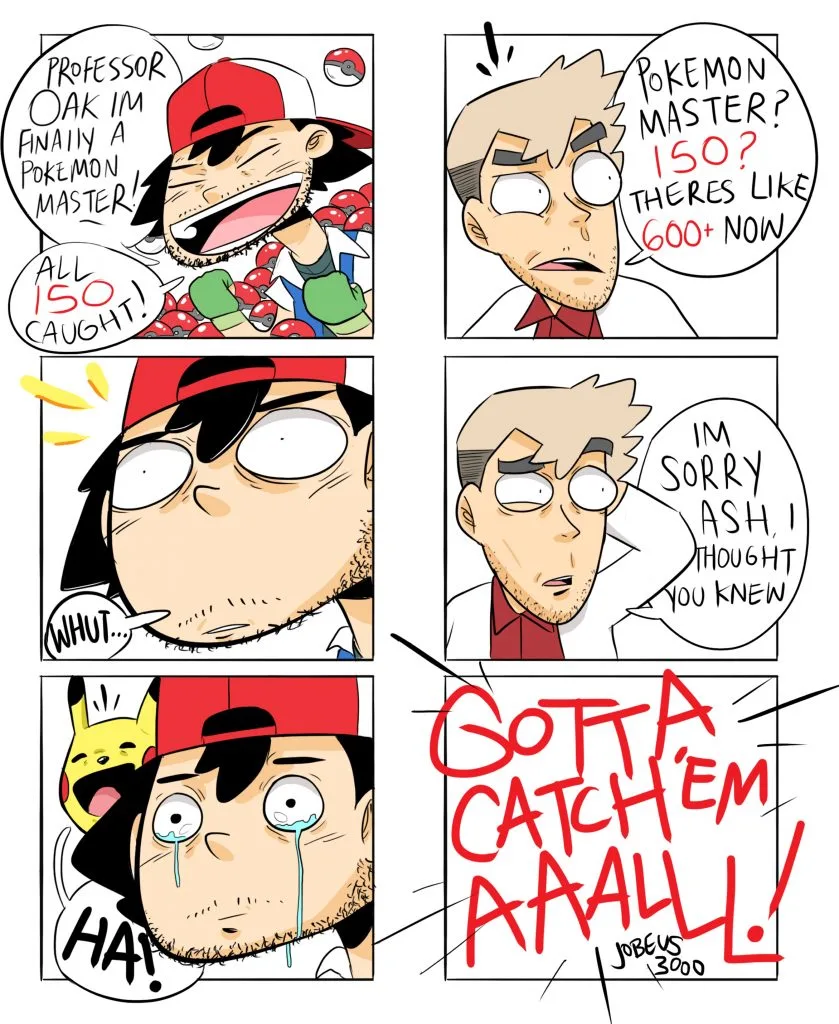

People who study fans talk of affirmative and transformative fandom. The former revere the original, core text and celebrate its every nuance. The latter, as the name suggests, take the core text and run with it, adding to it, changing it, creating new things to add to the world kickstarted by the author.

While Xena (Warrior Princess) and Gabrielle never got together in the actual show, the queer community filled the internet with art and fiction that said they did. The characters of Buffy the Vampire Slayer had whole other, non-canon, storylines invented by fans, playing up whatever part of the character spoke to them personally.

Fandom is a place for critique and discussion, where books, films and TV shows outlive themselves. None of this work, created by an insanely creative community, was intended or made for validation from those involved in the originals.

But as social media shrunk the world and lifted the barrier between fan and creator, things started to change. Fandom became less of a weird corner of the internet, and something more mainstream. It became a powerful tribal force that could be harnessed, lately, in the promotion of TV and movies.

In the last decade, as Marvel and DC movies stormed the box office charts and the San Diego Comic-Con became less niche and more Hollywood, the fans became the news. Photo essays of cosplaying attendees became a staple part of the media cycle. And since the creators are there in the booths or on the stages at the convention, cosplay became a way of interacting with that creator – by turning up at their signing, dressed as the character they created, telling them how much you love it.

But there are other ways of artistically engaging in fandom that don’t mean painting yourself green, wearing bizarre contact lenses, or carrying around a shield all day. Fan art used to have an unfair reputation but it has reached a level beyond that.

People make fan art for the same reason people cosplay – just to show their love.

It’s now an art form that professional artists play with as a daily work ritual. Comic artists make fan art as a warm-up exercise before they start drawing for the day, post it on social media, and watch it get swept up into something much bigger. A drawing of K from Blade Runner 2049, looking up at his hologram wife. Or Furiosa, from Mad Max: Fury Road.

The variation in the kind of work that gets made is extreme, but the common theme is that of the outsider – the people who don’t fit into the world, who have something to say but no way to say it, or nobody listening if they did.

“I think, in a broader sense, people make fan art for the same reason people cosplay – just to show their love,” says Ben Lee, a 39-year-old artist from Kansas City, Missouri. “Whether it be because of a lack of skill at construction, inhibition, or lack of time, we don’t cosplay, so we make art.”

Ben is among the many artists who create work based on the films of cult English director Edgar Wright, who made Shaun of the Dead, Hot Fuzz and The World’s End. His most recent film, Baby Driver, was not connected to the three previous films (collectively known as The Cornetto Trilogy).

Nobody knew anything about it before it was released in June this year. Which is why it was strange that the internet was flooded with Baby Driver fan art long before the film was released. What did these fans have to go on? They drew freeze-frames from the teaser trailer, and – knowing nothing about the film other than these few teased seconds – declared themselves Baby Driver fans.

So the PR campaign for the film harnessed the storm. There was a fan art competition to create a Snapchat filter, and Poster Spy started an alternative poster competition where the winner would be chosen by Wright. Submissions closed the day of the movie’s cinema release, when they would actually see the film they had decided they already loved.

Ben Charman is a 27-year-old freelance illustrator and animator based in Wiltshire in the UK. He started creating fan art three years ago as a way of gaining an audience, to bump his social media followers. “My reasoning was that people would automatically engage with it, as the TV show or movie I was creating fan art for would already have a built-in fanbase,” he says.

His alternative poster for Baby Driver was tweeted by Wright, which Ben says was a badge of honor, given that he has been a fan of the director since he (Ben) was 10 years old. “It’s always nice to get acknowledgement for you work, especially from the person you essentially made it for.”

But how do you know if you’re going to like something when it hasn’t even come out yet? “His work has a unique humor which really resonates with people,” Ben explains. “So every time he releases something new, the fans obsess over it. I think the love for the movie is also amplified because movie-goers are sick of reboots and remakes and when an original story comes along, particularly by a director they love, it’s hard not to get excited.”

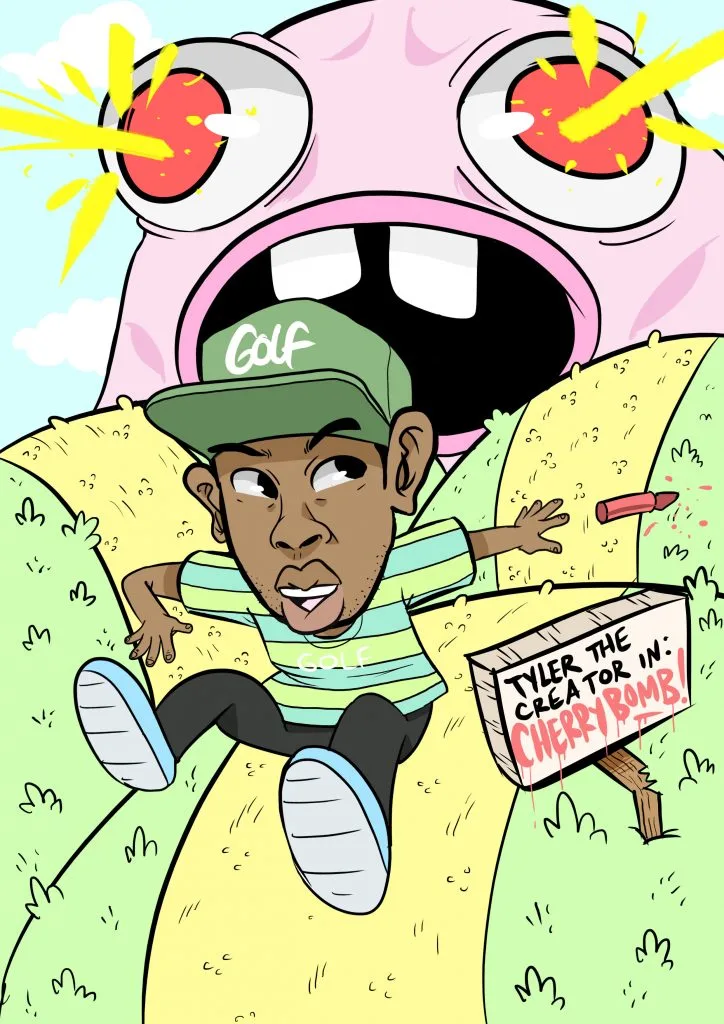

Jobe Anderson, 27, lives in Birmingham in the UK, and has been creating fan art since he was a kid. “It started off as something that just helped me draw,” he says. “Drawing random pictures of Spider-Man or characters from different games covers. But as I got older, it just became fun to draw your interpretation of other people’s characters, in your own style.”

Jobe was not surprised by the number of Baby Driver pieces he saw flying around on Twitter; his own was among the many that were tweeted by Wright himself. “People knew they were going to like Baby Driver because every film Edgar Wright had done before has been amazing, plus there was a lot of inspiration in the trailer. They saw bold colors, really animated characters and good music. That’s enough to inspire.”

So why don’t all films garner this kind of attention before release? There are plenty of films with bold colors, animated characters, and good music. Why Baby Driver?

These pieces are not created in a vacuum – it’s a conversation.

Because these things take hold when the art, or the artist, has been part of your life. With Blade Runner 2049, with Mad Max: Fury Road, these are longstanding franchises with deep wells of love in the fan community. With Baby Driver, there had been 15 years of anticipation, and the personal connection with Wright through social media pushed it to another realm. These pieces are not created in a vacuum – it’s a conversation.

“I wanted to write my impressions about the movies, but I’m not good at putting my thoughts into words” says Comaco, a 33-year-old Japanese artist and Wright’s most prolific fan-artist. “I decided to draw because I am much better at drawings than I am at writing.” Comaco redraws Wright’s Instagram photos and set himself a personal 30-day Baby Driver art challenge. Wright retweeted every one.

Sometimes, fan art is not just about being acknowledged, or being part of a community, or having a discussion with other fans. Occasionally, there are other things at play. There’s always the chance you can get a job out of it.

In one of the less famous comic book origin stories, Jill Thompson got her gig drawing Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman through a piece of fan art, or rather, art for a fan. She was already an established comics artist by this point — her regular gig was on DC Comics’ Wonder Woman — when she was approached by a man at a comic convention.

The guy wanted a picture of Death, naked. Not Death with the black cloak and the scythe, but Death, the cute gothy character from the Vertigo comic book series, The Sandman. Thompson dutifully sketched Death naked, and the same fan lined up to get her drawing signed by Gaiman. The author loved it, and when he met Jill later that day, he offered her a Sandman storyline all of her own. It only partially cooled her blushing face.

So fan art is a way of being seen.

Ben Lee agrees: “In pivoting my career to a full-time artist, I would be lying if I said I didn’t hope to get noticed by someone with decision-making power to create art for the entertainment industry,” he says. “That would be amazing. But it’s by no means the primary goal.”

His primary goal? Just being noticed by Edgar Wright. “Being a big fan of his, of course I wanted to try catch his eye.”

This enthusiasm can be harnessed to make a film a success, but their new ideas can also become part of the worlds they love. Art is a dialogue, and fans have something to say.