The fairgrounds of today are often dominated by exhilarating drop towers and swinging pendulums that would have been unheard of a century ago. But decorating the rides and booths, you’ll find an aesthetic tradition that goes back generations—a tradition that encompasses lettering and woodcarving, scrollwork and metalwork, and a distinctive vocabulary of figurative motifs. Writer Damian Le Bas, who grew up marveling at the fairs and the proud Showmen who brought them to life, explores the history and evolution of fairground art, and its perennial ability to entice, awe, and inspire.

When I was a kid, I knew a young man who worked on the fairs. Our families, being of traditional traveling stock, were acquainted from generations back. He was 10 years older than me, perhaps, and had crow-black hair, pale skin, a small earring, and a grin like a slither of moon. The effect was a resemblance—of cheek as of physical look—to the cartoon image of Captain Morgan, as seen on rum labels worldwide. I will call him T.

T. was descended from long lineages of mobile English showpeople (or “Showmen” as they tend to refer to themselves, irrespective of gender). He possessed a mix of charisma and deftness of hand that earned him a decent living on the road. He had a stand-the-bottle-up stall—a simple carnival game which T. presented with great panache. Using a pole from one end of which dangled a small wooden hoop on a string, he could, with great elegance, tease a huge glass bottle from lying on its side to standing upright on his table. He would do it in front of the crowds, his gaze fixed on the bottle with a snooker player’s intensity. It looked tricky, but doable enough that any young buck with a few beers in him would wager a pound to win 20 that he could reenact what T. had just done, and impress his friends into the bargain. Sometimes girls would have a go, but T.’s bread-and-butter seemed to be the young man who couldn’t stop trying until he’d run out of coins.

In a week-long stay with my grandparents at the Great Dorset Steam Fair in England, I never saw anyone except T. stand that big glass bottle up. When a punter had failed, T. would sometimes wink at the crestfallen man’s girlfriend and then, whilst maintaining eye contact with her, flick out the pole and string to one side and stand the bottle up without so much as glancing at it. Sometimes, when bored or between customers, he’d produce his guitar, a plectrum, and a sandy, baritone voice.

I wanted to be like T. In between rides on the waltzers and gallopers, and evening walks around the great ring of burgundy steam engines with their twisted brass adornments that shone in the dusk like solid gold, I liked to watch T. work and listen to stories about his life. He always used to speak of being “open on a ground,” which was when the Showmen would turn up on a town green, a strip of seafront or recreation field, and skim the place for its money and maybe a twirl with the local girls. All this in exchange for staying up late, being willing to talk to whomever the tide brought by, and long winter hours in the off-season spent repairing the rides, maybe running an indoor arcade, and practicing how to stand heavy glass bottles upright.

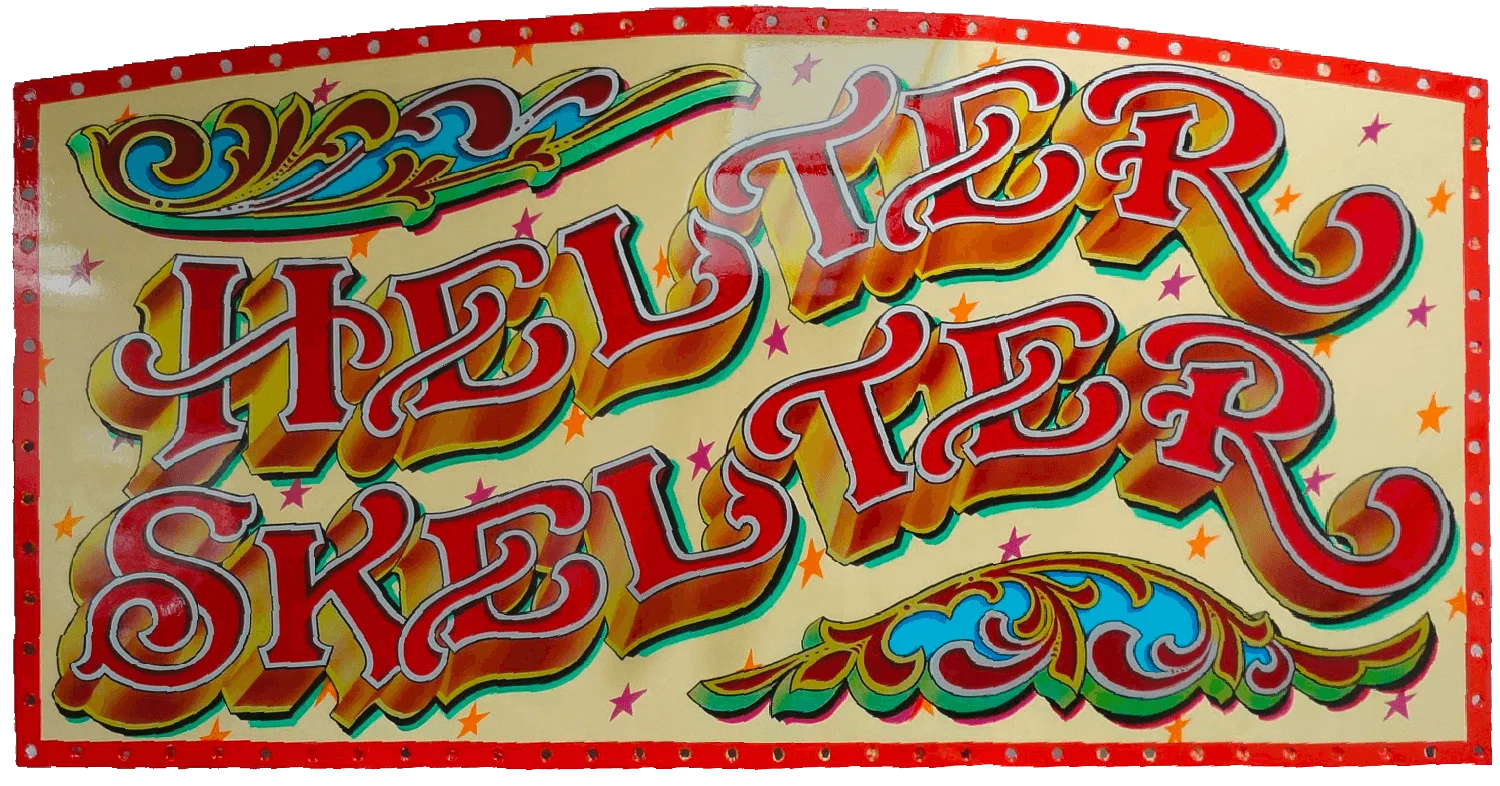

And T. had to maintain his stall, of course, the little mobile theater of his beaming one-man show. It had a segmented circular roof like a medieval army camp tent, and glossy wooden hoardings lined with colorful enamels and bright gold leaf. The stall had a look of the wagons in which my ancestors used to live. But while my Romany family’s vehicles existed solely to be slept in after a hard day’s graft on the farms, the Showmen’s working time stretched into the darkness. From their transports, they would unfold brazen signage onto which they had painted their old enticements: the names of their “amusements” (GHOST TRAIN, SHOOTING GALLERY, GALLOPERS, WALTZER) and the families who were trusted to provide them (SMART’S, COLES, STEVENS, HARRIS’S). When you saw those words, and the painted faces and gilded scrollwork swirling in between them, you knew you were guaranteed a good time.

“Fairground art is art mixed with commerce,” says filmmaker Charles Newland, who grew up in a nomadic Romany Gypsy family.

Newland is descended on his mother’s side from traveling Showmen who, for generations, worked Nottingham’s Goose Fair—one of the largest and oldest seasonal funfairs in the British Isles. Anthropologists have long called both Showmen and Romany Travelers “commercial nomads,” and when I call Newland to talk to him about the topic of fairground art, his mind quickly moves in a monetary direction.

“Those rides aren’t painted like that just for the sake of it, because it looks nice. It’s business,” he says. “It stands to reason that the most attractive ride is going to attract the most people to it.”

Steam-driven old-time gallopers (traditional carousels, with rising and falling animals to ride on) have mostly given way to electric- and diesel-powered pneumatic drop towers and pendulums. But the motive behind the fair remains the same. “That’s always been the purpose, to bring in money. It’s why they still spend good money getting the rides painted like it today. Like the ones with gigantic Hollywood superheroes on them—nothing brings in a crowd of young people like a 40-foot picture of Spiderman or something like that. The art always worked. And it still does.”

“The art” to which Newland refers is the painting of the attractions, and this has always been inextricable from a complex tradition of ride engineering, woodcarving, and metalwork. The addition of color to the whole has always been the finishing touch, but a touch of crucial importance.

Fairground art evolved in tandem with the technological advances of the Industrial Revolution, when workers thirsted for recreation in the midst of often hard and dreary lives. In order to convince a hard-pressed public to spend their money, the artwork needed to be two things: spectacular, and universally attractive. The aesthetic produced by these twin requirements was a colorful, gilded marriage of the naturalistic with the outlandish. Animals—lions, elephants, swans, storks, and, of course, horses—were often the focus, as well as imaginary and chimerical creatures like mermaids, sea monsters, dragons, and centaurs.

Although many Showman artists have hailed from traveling families (some bear surnames that are also common in the Romany Gypsy community) there is an obvious tension between the mobile nature of the touring amusement business and the need for a permanent workshop in which to build, paint, and restore rides and stalls. The road is a hard place for a painter to maintain a steady hand. As a result, even seasonally nomadic fairground signwriters tend to have yards where their workshops are situated, and in which they spend a considerable part of their time.

In this respect, their lives have long mirrored those of Europe’s other ethnic nomadic communities, who often hunker down for the winter on an owned or rented family lot. The ability to park trailers and mobile homes long-term, without the hindrance of having to move when the days are short and full of bad weather, is a blessing whatever the family business might be. For a fairground artist, tasked with keeping large and valuable sections of someone else’s ride safe from the elements while they set about making them marvelous, a barn or large open studio is more or less a necessity.

The showground is an old form of transferring information. It’s communicating new ideas in the most traditional way, going from place to place, from A to Z.

Whether nomadic or not, what fairground artists have always had in common is the need to be able to imagine, carve, and paint with equal brilliance. In the early days of the profession, famous names included Charles Spooner of England, Alexandre Devos of Belgium (who started off making church statues before turning his hand to the secular wonders of the fairground), Friedrich Heyn and Eduard Leitsch of Germany, Louis Lesot and Léon Morice of France, and the great fairground artists of the United States (many of whom—like the renowned Solomon Stein, Harry Goldstein, and Charles Carmel—were from European Jewish families).

Nowadays, some ride owners simply commission vinyl wrap overlays to add pomp to their machines and stalls, but until the 21st century, fairground art was produced the old way: by hand, with brushes, paints, gold leaf, and glaze. Whether the paint was applied to carved wood or to cast metal, the overall fairground look remained the same—electric light bulbs, large promotional lettering, scrollwork and geometric patterns, and a rainbow of color.

By the interwar period, the technique used to paint fairground rides and stalls had settled into a received practice. The craft was literally multilayered, because the paintwork had to be able to withstand the often inclement weather of places like northern Britain, the Low Countries, and the northeastern United States.

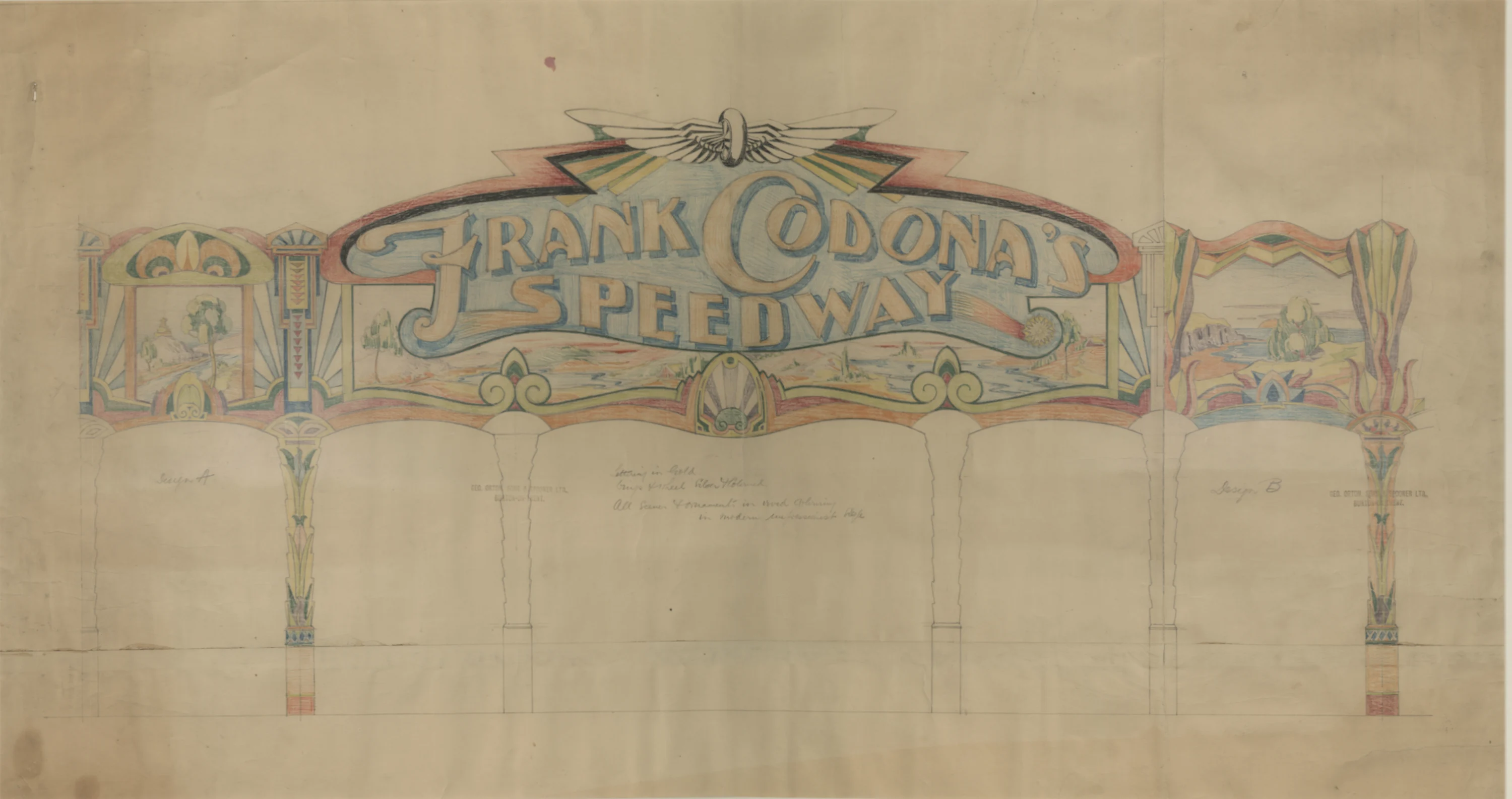

First, the artist lays out their design on paper. This includes any lettering (the name of the fair-owning family is usually prominent) and scrollwork, as well as figurative elements like human faces, which vary enormously depending on the theme of the ride. These designs are traced onto the surface of the attraction, then painted over using silver paint or aluminum leaf, also known as imitation silver leaf. This metallic base is painted over using translucent colored paints called flamboyant enamels, which allow the luster of the metal underneath to shine through and reflect the electric lights of the fair. Fine black lines give definition to the shapes and words, and, finally, the work is varnished against the elements.

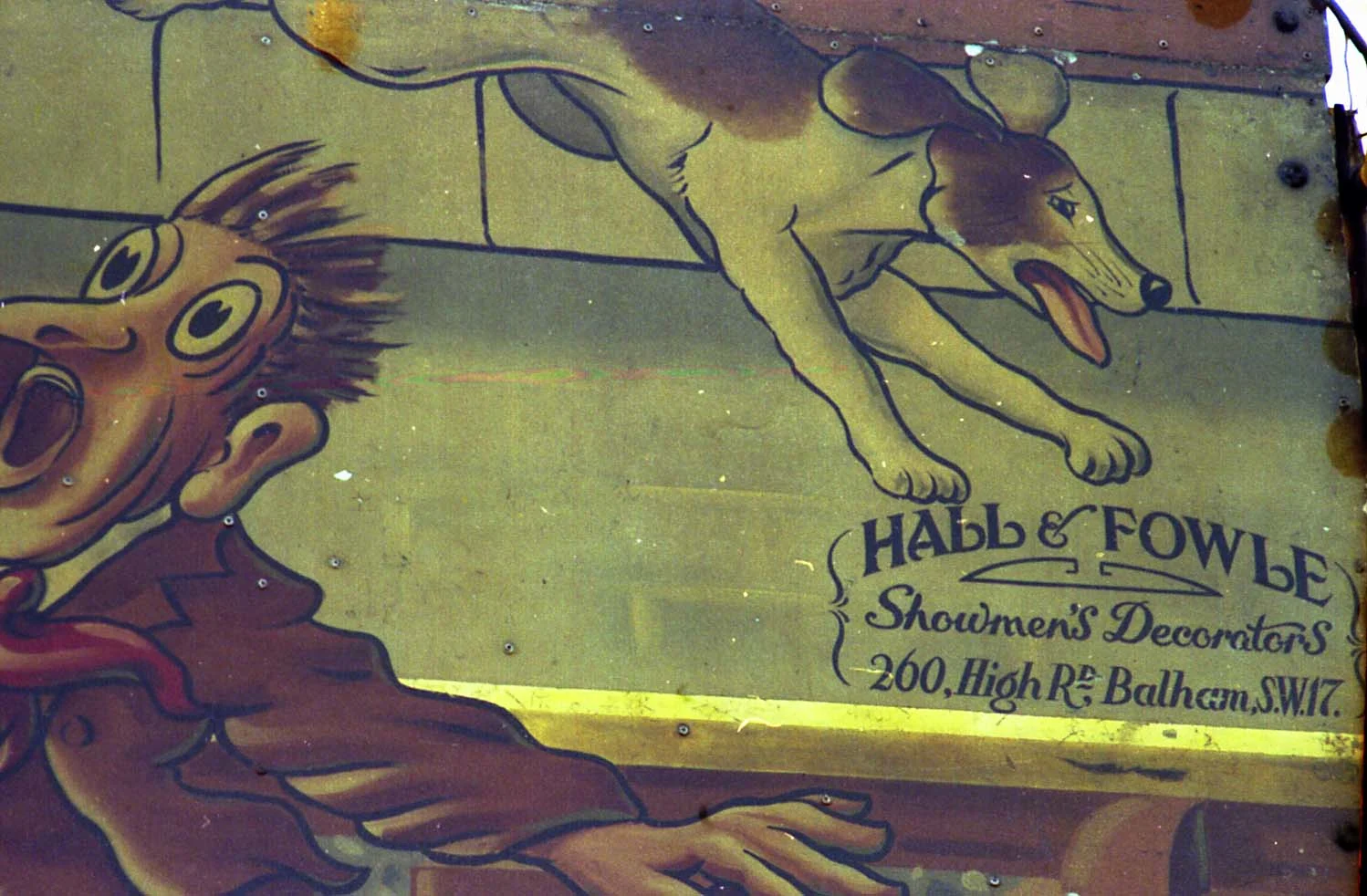

This process, which present-day practitioners of traditional fairground signwriting still follow, has seen negligible change over the past hundred years, since the days of the lions of the trade, including Sid Howell, Edwin Hall, and, perhaps most famously, Fred Fowle. Fowle, who was also known by the moniker of Futuristic Fred, had apprenticed for Hall as a teenager in the 1920s and 1930s. In a career spanning six decades, he used his inherited painting techniques to take fairground aesthetics in new directions. Influenced by the cultural movements of his time, Fowle came to embrace blocky three-dimensional shapes alongside the more traditional scrollwork, with its echoes of feathers, scallops, and fleurs-de-lis. His work pulsed with an overtly psychedelic feel and the thrill of speed and danger, its cosmic dimension augmented by his use of sparkling glitter paint. Fowle was known for layering color to achieve startling depth and brilliance.

Spraypaint and airbrushes are nowadays used by some, but in Britain, traditional signwriters like R. J Thomas, Amy Goodwin, Joby Carter, and Harley Harris, tend to veer little from the practices of the 20th century masters. Adeptness at fairground lettering remains a requisite of the job. “There’s so many facets to lettering that people don’t understand,” Carter says in a 2019 docu-series produced by his family’s traveling fair.

“These days people print things on a computer and that’s it: easily done. Back in the day, people doing newspapers had to lay it all out and print it. … Everything was done by hand. ... When people wanted to convey a message, it had to be signwritten. It couldn’t be stuck on with sticky letters. Now, there’s nothing wrong with sticky letters. ... But for what we do, with heritage equipment, my belief is that when you restore something, it should be done in the same fashion that it was done when it was new.”

Lettering is central to the discipline of signwriting, but the principles of font are often unknown to those who have never undergone an apprenticeship. “When I teach people, I knock them back to a [basic] font like Roman,” says Carter in the video. “When you do a Roman A, [you do] a thin stroke and a thick stroke, and the thick stroke is always on the same side. The proportions should be nicely proportioned so that the space [in the top half of the letter] and the space [between the ‘legs’ of the A] look right. And feel right.”

A signwriter must also understand the principle of optical refinement—of prioritizing the painting’s effect on the eye over concepts like symmetry and mathematical precision. “People perceive an ‘O’ as an oval,” says Carter, “when often they are as tall as they are wide. ... So that’s a common mistake when people are doing Os. ... If you can’t do the basics , then you can’t do the fancy stuff, you can’t do the block and the shadow.”

The result of fairground art, ideally, is what artist Sam Haggarty—director of the Unfairground, an iconoclastic take on the traditional English fair at Glastonbury Festival—refers to as “wonderment:” the sense of awe which the showground needs to supply in order to lure in customers.

“You take a space and you turn it into a palace, and that palace lives on,” says Haggarty. “The Harrises have the same rides they’ve had for 120 years. Their yard is a treasure trove. The gallopers, the Chair-O-planes… Imagine seeing that for the first time. The modern fair operator, he adds, is essentially still trying to achieve that effect now. He conveys a sense of the fair as a gigantic jack-in-a-box: compressed contraptions leaping out of dark boxes.

Like Newland, Haggarty lights on the problem faced by latter-day Showmen: that modern customers, especially children, encounter visual spectacle constantly in the palms of their hands. The lights and colors of the fairground are no longer a wondrous anomaly in the lives of working people.

The surfeit of superheroes and film stars that appear on the rides nowadays, according to Haggarty, are there to entice kids—“to make that link to what they see elsewhere.”

“The Hollywood thing is about competing in an already consumed environment,” he says. But the rides offer something that other entertainment media can’t—often “a gut-wrenching G-force experience,” as he puts it. And you can’t have those sitting on the couch and staring at your phone.

The visual spectacle, though, will always come first. “If you look at traditional fairground frontages, they present the fantastical. Almost to the extent of being religious art—the gold, the colors. The wonder of what you can’t afford,” Haggarty says.

I float the idea that fairgrounds provided the spectacle of religious grandeur, but without the moral oppression. “Well, moralistically there would have been objections to the fair, particularly in the late Victorian period. Objections to the public’s desire for the gaudy, the odd, the outrageous.” There were people who didn’t believe that appetite should be fed. This certainly applied to sideshows of human “freaks” and “geeks,” attractions which are unthinkable now.

I mention the importance of lettering and fonts, and Haggarty explains that their colorful and often florid designs are intended to beckon the onlooker, even if they are non-literate, which was the case for many customers of early fairgrounds. “Whether the person looking at it can read or not, it still tells them something. It’s about welcoming,” he says, and he argues that lettering must always be seen within the context of the entire fair being essentially a grand act of communication.

“It’s information, isn’t it?” he says. “The showground is an old form of transferring information. It’s communicating new ideas in the most traditional way, going from place to place, from A to Z.”

The fruits of recent scientific advance would also be center stage, and the effect they once produced remains the goal of the modern Showman. “They used to show the electric light bulb or a sewing machine. People couldn’t imagine a human could invent something that stitches your trousers. Or if you’re a sheep farmer who’s lived by candlelight all his life, imagine seeing a light bulb that just turns on and off. Look at this wonderment! That’s what it’s all about.”

Image credits

1 Image courtesy of the National Fairground and Circus Archive, University of Sheffield Library: Sid and Albert Howell Painting Ark Front: Jack Leeson photograph, Birmingham Whit Fair, 1959.

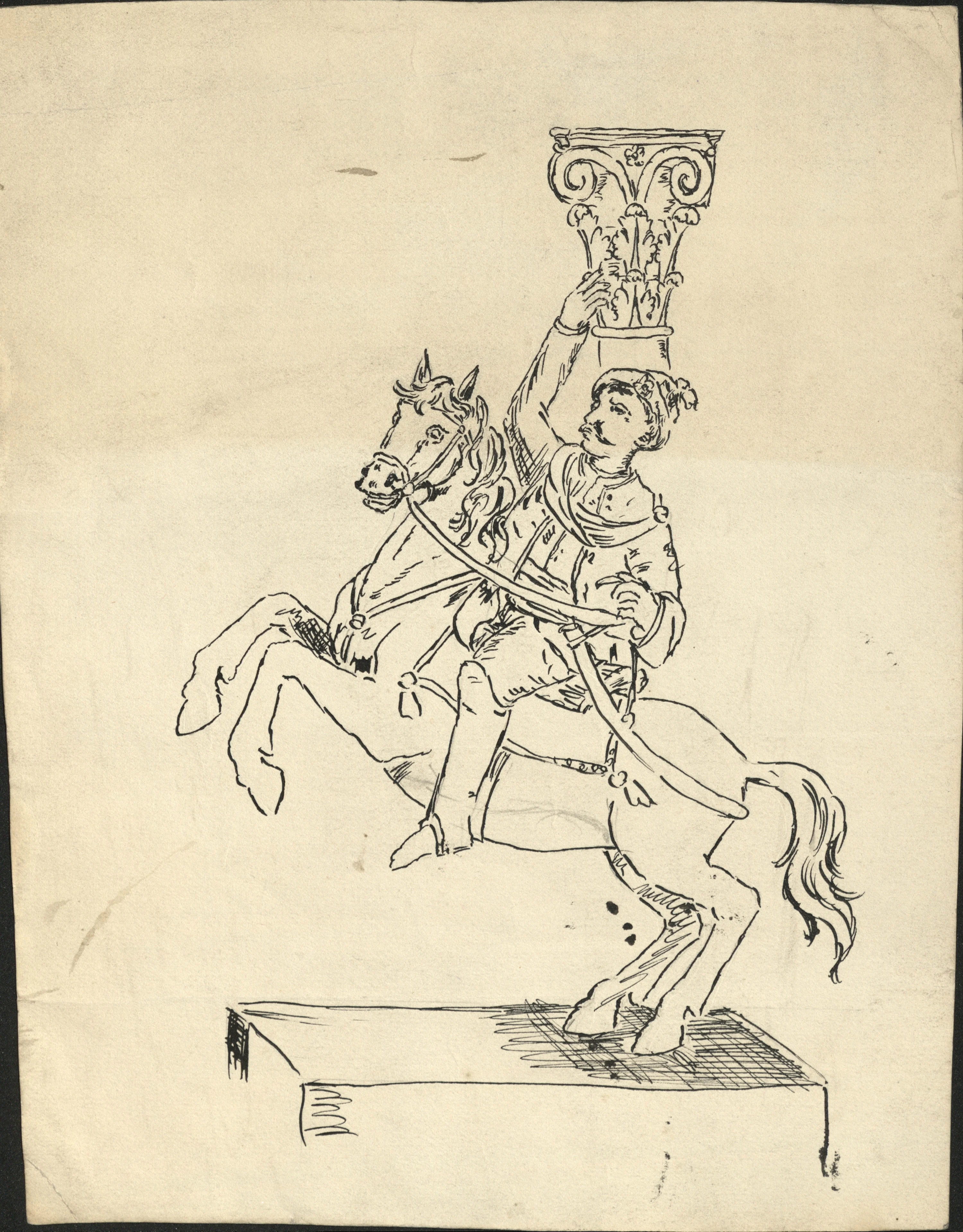

2 Image courtesy of the National Fairground and Circus Archive, University of Sheffield Library: Design of Rearing Horse Column

3 Image courtesy of the National Fairground and Circus Archive, University of Sheffield Library: Frank Codona's Speedway Frontage

4 Image courtesy of the National Fairground and Circus Archive, University of Sheffield Library: Stephen Smith photograph, Newcastle Town Moor Fair, 1981.