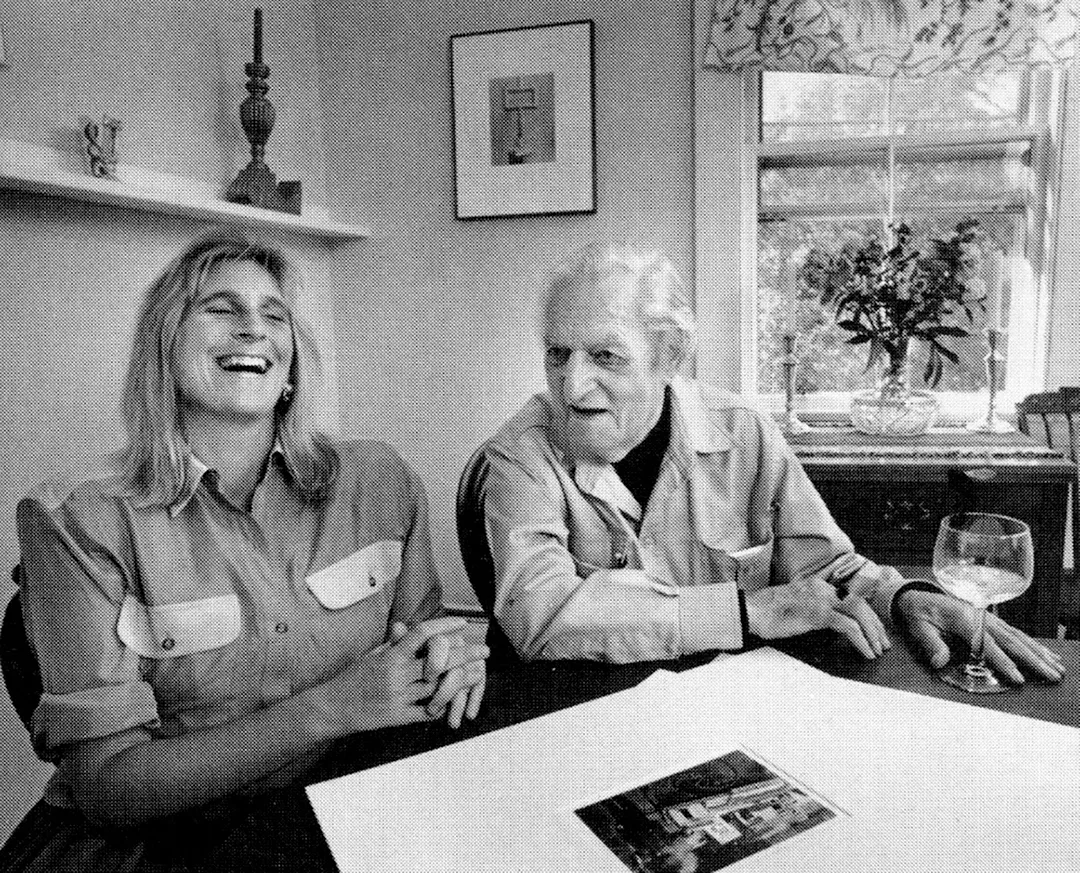

The photographs featured in this article are taken by one of the most exciting and important photographers of the 20th and 21st Century. The thing is, you’ve probably never heard of him. Word’s getting out about the truly extraordinary life and work of this artist, and it’s all thanks to one woman who has dedicated her life to his legacy. Writer Michael Segalov travelled to Portland, Maine, to ask Betsy Evans Hunt why we need to know more about Todd Webb.

It’s been 20 years since Betsy Evans Hunt last made the 30 mile drive to Bath, Maine from her home in Portland, although she still remembers the route perfectly: north up Highway 295 and onto the coastal town’s quaint High Street, past the Chocolate Church Art Centre and towards peaceful, leafy drives.

When we pull up outside the house we have come to visit, she quietens. For an hour Betsy has regaled to me stories of happy times she spent here in generous detail, describing the meals she had eaten and the friends who’d come and go. But as she steps out and points up, talking me through what used to sit inside – the steep colonial stairway leading up to a desk and typewriter; the furniture from New Mexico, the “dumpy” kitchen and the photography covered walls – Betsy takes a moment of reflection to herself.

“Todd and Lucille were basically family to me,” Betsy says, of the couple who used to live here, “and I definitely became a daughter to them.” From the day Betsy and Todd Webb first met in the late fall of 1989, their lives became inextricably linked. Todd was warm, unpretentious and generous; absurdly modest about all he had achieved. It’s why he and Betsy quickly became friends, then practically family, and over time something even more profound.

Since Todd passed away in 2000, just days before his 95th birthday, it’s been Betsy’s mission to ensure his life’s work has a legacy, that it gets the recognition she believes it truly deserves. Because despite being one of America’s great photographers, for too long Todd’s work was forgotten. And if it wasn’t for a series of unlikely coincidences, chance encounters, and an unexpected but powerful bond between two people, the likelihood is that would never have changed. If you ask Betsy, she reckons it was fate.

There’s a large wooden table back at the Todd Webb Archive office, two computers and heaps of storage in all corners of the room. Surrounded by Todd’s work, which hangs in pride of place on the walls, it’s from here in the Old Port area of the city that Betsy and her colleague Sam go about their work: cataloguing Todd’s archive and handling sales, but most importantly coming up with new ways to introduce collectors, curators, critics and the public to his genius.

As we sit down opposite each other, Betsy tells the story of how her life came to intersect with Todd’s. A child of the 1950s, she grew up in New Jersey, before heading west to Colorado to study art history at college. Her senior thesis focused on Alfred Stieglitz, his wife American artist Georgia O’Keeffe, and Stieglitz’s influence on modern American painting. Betsy quickly became fascinated by the legendary photographer and promoter, widely recognised for ensuring photography became a respected form of artistic expression. After graduating in 1977, she headed to California, finding work in the photography galleries of San Francisco during one of the most exciting times for the field.

“Oh my god, it was amazing,” says Betsy, grinning. “It was such a great time to be involved because photography was coming up nationwide. Between a couple of collectors like Sam Wagstaff and Graham Nash, and a few high profile museums, American photography was storming the art scene.”

The works of America’s great photographers were passing through Betsy’s gallery: Robert Frank, Walker Evans and Danny Lyon to name a few. She was still in her early twenties, but both her contact book and knowledge of the industry would set her up for decades to come.

Seven years after leaving the east coast, Betsy decided it was time to head home. Within days of arriving in New York she bagged a job assisting Robert Mapplethorpe. “I’d get there at 11am because he liked to sleep in,” explains Betsy. “He really hadn't had anybody helping him out before, he was incredibly disorganized.” She set to work trying to bring some order to his genius, helping out when the likes of Liza Minelli, Donald Sutherland and Richard Gere arrived at the studio for shoots. Once it was time to move on, Betsy travelled all over, but she refused to settle, never quite finding her place.

When we arrive back at her office, the late November sun is setting. On the drive home, Betsy has guided me through what the years that followed had in store. She sewed sails on the US Virgin Islands in the early 1980s; she found a job cataloguing the collection of an art museum in Massachusetts, before enrolling on a course run by Sothebys in modern American arts. She moved to Portland on the US’s north-eastern coast in late 1987 when a job in the antiques business came along.

Some people never find their calling, and I certainly wasn’t seeking it.

And then in May 1989 she found herself at something of a crossroads, without direction or an obvious plan. She’d quit her job and headed out to LA a few months earlier to spend time with her brother Peter, who was dying of AIDS. Betsy arrived back in Portland with a new-found determination. The grief and pain somehow pulled her life into focus and she wanted to find her calling. Opening a photography gallery, given her connections and expertise, seemed like a perfect place to start.

The doors to Evans Gallery in Portland opened in September 1989, just down the road on Pleasant Street from the office in which we are now sitting. Despite being a relatively small operation, Betsy secured shows with big name photographers: Eliot Porter, Walker Evans, Robert Frank. “There was a fair amount of news reporting about the exhibitions,” says Betsy, opening up her scrapbook. “At this time Portland was still quite a small, sleepy town.”

Todd and his wife Lucille read about the gallery in the local paper, and began to visit to see the shows.

“In the gallery we’d overhear this old couple talking to each other about how they knew all the photographers we were showing,” remembers Betsy, fondly. “‘Gosh,’ Todd would say, ‘we knew Ansel before he had his beard and got expensive;’ or ‘I worked with Walker Evans,’ or ‘Robert Frank came to our New Year’s Eve party in Paris one year.’”

Betsy was fascinated by the Webbs, both now in their mid-eighties. Who was this adorable old couple? How did they know so many of her photographers, and so well? Finally, she went over to introduce herself. There was an instant connection between the three of them, and Todd told her he was a photographer as well.

“When I asked who represented him, there wasn’t a gallery or agent. He just said he’d had a really awful experience and that he didn't care if he sold another picture in his life.”

And that’s how Betsy Evans Hunt first met Todd Webb.

Todd Webb was born on 15 September 1905 in Detroit to a family of quakers; he spent his teenage years in Canada living with his grandfather, before returning to the city of his birth to become a banker, aged 25. In 1929 the Wall Street Crash left Todd and many others with nothing, and so he packed up what he had left and headed west. For a while he led something of a nomadic lifestyle: he bought a donkey and a tent and panned for gold in the hills of northern California, then he moved to San Francisco picking up whatever odd jobs he could. In 1934, he returned home to Michigan to a copywriting job with Chrysler. A colleague pointed out everything he wrote was full of visual details, and that maybe he should give photography a try. It was then, at 35, that Todd picked up a camera for the very first time.

He joined the company’s amateur camera club and struck up a friendship with Harry Callahan, a fellow Chrysler worker. Callahan would not just go on to be one of the most celebrated American photographers, but also a lifelong friend to Todd. Still, that would all come a long way in the future. For now, the pair were content exploring their new found passion, guided by Ansel Adams who tutored them during 10 workshops in 1941. Back then, Adams wasn’t quite yet the icon he went on to be, in the same year he was contracted with the Department of the Interior (DOI) to take photographs of national parks.

“This changed both of their lives forever,” explains Betsy, whose knowledge of Todd’s life – drawn from both the time they spent together, and his meticulously kept journal – is close to encyclopaedic. “They both just became obsessed with their cameras, desperate to quit their jobs and become photographers. And so they did, heading to Colorado to take photos in the mountains.”

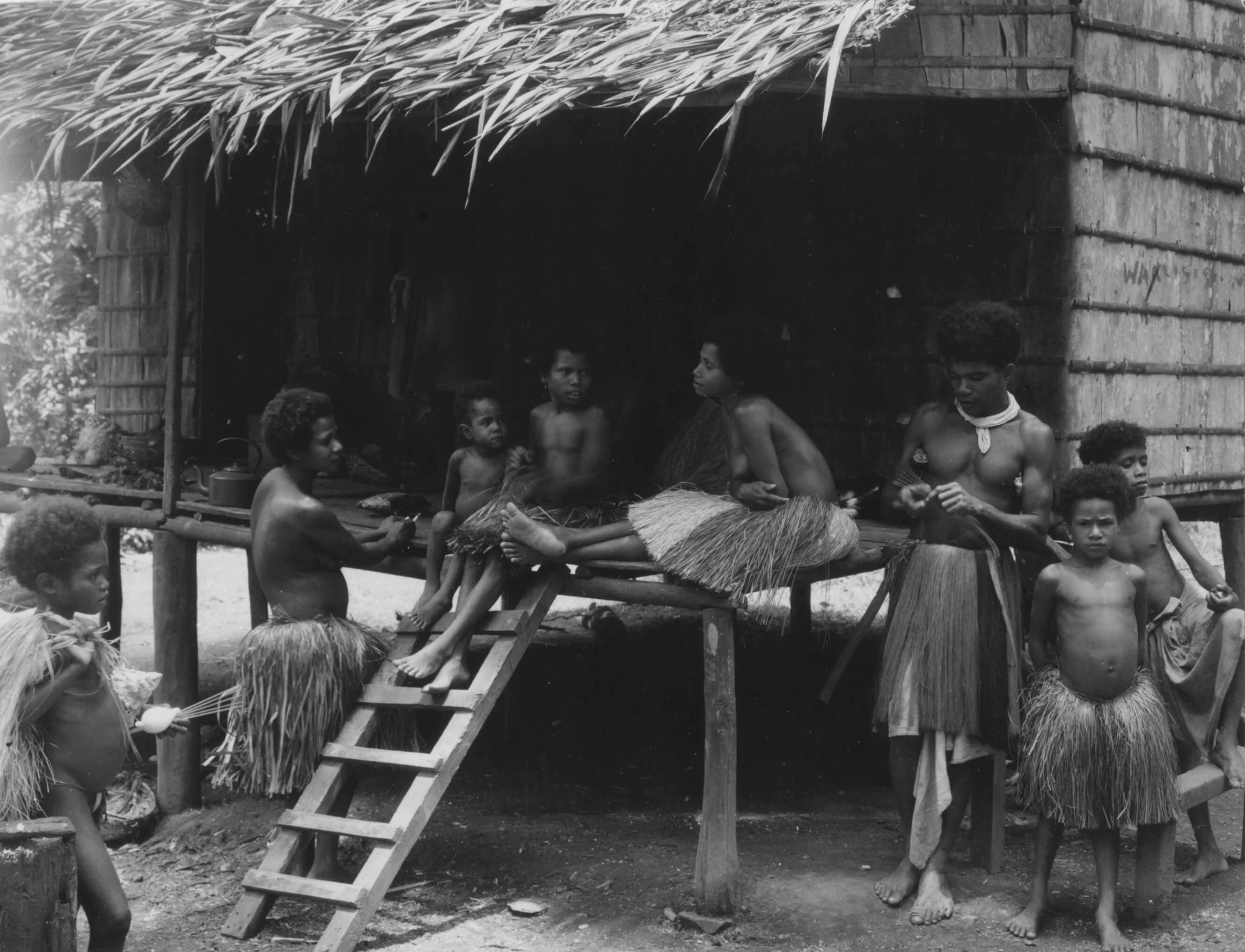

Once the United States joined the Second World War, Todd conscripted as a photographer in the navy and was sent to New Guinea where he served three years. She shows me the photos Todd took while he was out there: not of war, but the everyday lives of the local civilians.

On leave in 1943, Todd took a trip to New York City where Ansel Adams, his tutor and mentor, had arranged a meeting with Alfred Stieglitz: the man who, more than 30 years later, would shape Betsy’s entire life. Todd showed Stieglitz a body of work he’d completed: a series on an African American family back in Detroit. Betsy pulls out the photographs from a drawer.

“Todd and Stieglitz struck up a friendship,” says Betsy, “he saw himself in Todd. After the war was over Todd rented a place in Harlem, and set about town in search of work.” By now Todd’s in his forties. A few years prior to this moment, he’d never even taken a photograph, but his eye and the natural talent he clearly possesses begins to speak for itself. Within a few months Todd has secured enough work to sustain himself and within a year his first solo show at the Museum of the City of New York is confirmed.

What followed is a fascinating life worthy of a feature-length biopic: Todd is sent on assignments by Standard Oil across the United States and beyond, before falling in love with Paris in 1948, a city he later moved to. He worked for the United Nations and the Marshall Plan capturing a world in the midst of a post-war transition; he met his future wife Lucille and together they saw the world. Once work dried up in the French capital, the couple moved back to America, and in 1955 (and 1956) Todd was awarded the Guggenheim Scholarship to document life in the United States by travelling across the country on foot.

The pictures from this trip paint a picture of someone warm and playful, he posed for self-portraits depicting with characteristic humour his day to day. He spent time with Georgia O’Keeffe at her Santa Fe home (the two had met on the first day Todd had arrived at Stieglitz’s gallery) Todd had supported the grieving widow as she mourned her husband when he died in the summer of 1946, a kindness she’d never forgotten. The photographs he took of Georgia during this time are strikingly candid – the type of photographs only a relationship built on trust can produce.

In 1975, while Betsy was immersed in the ascent of photography in California, Todd’s prospects were about to take a turn for the worse. After Lucille was diagnosed with cancer the couple relocated to Maine, when a profit-hungry dodgy dealer appeared in their lives.

“This guy shows up in Maine in a Rolls Royce, talks a big game, and offers Todd $60,000 to buy his whole collection,” explains Betsy, ordering another Diet Coke. “That seemed like an enormous amount of money at the time, especially given the price of photographs were only just starting to rise. Todd never wanted to tell me exactly how much of his work he sold off.”

A deal was done, Todd’s work was packed away, but aside from just two instalments the rest of what Todd was owed never got paid. “He was very frustrated,” explains Betsy. “He was never paid the money he was owed, and it wasn’t even as if the dealer did what he should have to lift Todd’s work properly.”

Todd and Lucille wrote letters to the dealer, but he never got back to them. And despite having been shafted, Todd had signed a contract. He never quite knew where he stood, so feeling dejected and well into his seventies he all but gave up. Well, that was until the Webb’s met Betsy a decade later. Without any children of their own, Todd and Lucille never had anyone fighting their corner; even if they’d managed to claw back the archive that was stolen from them, who would look after it? Would would be the point?

Todd was left hurt and hopeless about the prospects of seeing his work being truly recognized; it’s why unlike his contemporaries, Todd never really found commercial success. All that changed as their relationship with Betsy began to blossom. It took a while, but over their lunches – at first monthly, but becoming increasingly regular – Todd and Lucille let Betsy into their world and they opened up.

“Pretty early on in our friendship Todd mentioned he knew Stieglitz,” says Betsy, “I was gobsmacked; firstly he’s like the god, and secondly I’d written my thesis on him. And then I found out that they were great friends with O'Keeffe. These are icons, you know? The people I had studied. I was like; ‘God, this is amazing!’ And Todd and I just got on so well, there was this immediate connection.”

Betsy appreciated Todd’s work, but also his character: unpretentious with no time for bullshit, just like her. Take the time Todd was teaching a class of college students, he was asked what makes a great picture. Todd’s answer? “You just have to know where to stand.” When showing O’Keeffe how to take photographs, he spent five minutes going over the basics, passed her the camera and declared that she already knew the rest. Todd didn’t have anything to prove – photography was in his bones.

“It probably took about a year for me to gain his trust enough to look through what he had left of his work, what he still had was in boxes at home,” she continues. “There was this huge lightbulb going off in my head: he needs to be better known! Why isn’t he!?”

Evans Gallery closed in 1993, but by then Betsy had realised she wasn’t built for the hard-sell of retail. Instead, having gained the Webbs’ trust, she set out showing and selling Todd’s work on their behalf. Todd was 34 when he first picked up a camera and found his calling; Betsy was the same age when – thanks to Todd’s work – she found hers.

To this day, Betsy carries with her a small box of Todd’s ashes to make sure he’s by her side.

Todd’s photography doesn’t just decorate Betsy’s office, there’s plenty to be found at her home down the road from Portland in Cape Elizabeth, which looks out over the Atlantic. We’re sat by the fire, a bottle of white wine for company, her husband Chris and his impressive moustache have joined us too. Before Todd and Lucille died, they asked Betsy if she’d take on their estate, inheriting Todd’s archive and the responsibility that came with it.

“They were writing their wills and figuring out what they were going to do,” Betsy explains. “I think they could see I was making some inroads in elevating his stature – making sales and so on – and realized leaving it to me might be worth a shot.”

“I don't think they would have ever thought…,” Betsy says, briefly pausing. “I mean, maybe they’d have dreamed that I would do what I’m doing now, but I really doubt it.”

Because for 11 years now, Betsy has dedicated her life to Todd and his work. Harnessing the skills she acquired in all the jobs along the way, and driven by the depth of their relationship, Betsy has taken it further than either of them could ever have expected. The breakthrough came in 2017 when she secured a show for Todd’s work at the Museum of the City of New York, 70 years after Todd had his first solo show there. Doing that was the impetus for Betsy to track down and buy back the missing archive, too.

A gallery in Northern California was occasionally selling pieces of Todd’s work on ebay, Betsy got in touch to track down the source of its supply. “It turned out these three guys from Berkley were consigning the photographs to the gallery,” says Betsy, “so I headed out there to see what was what.”

What she found was five steamer trunks full of Todd’s whole life: his journal, prints, his travel logs, key negatives, vintage work from Paris and New York. And a collection of breathtaking and beautiful colour negatives from Todd’s time working in Africa in the 1950s as colonial rule was quashed and independence beckoned – the likes of which experts I speak to who’ll curate an upcoming show have never seen.

“I was completely overwhelmed, but tried not to show it,” she continues, “I had mixed emotions: I was thrilled to find it, but also understood properly for the first time the depth of Todd’s grief. He never wanted to talk about it because it was his life, his prize.” She considered legal action, but that could’ve gone on forever. And Todd never elected to that either, she didn’t want to betray his legacy that way.

“You catch more flies with honey than vinegar,” says Betsy, explaining her thinking, “so I appealed to their good nature: don’t you think Todd would rest so much more easily, I said to them, if all his pictures were together at last?” She came up with a figure, and bought the collection back.

Now she’s separated Todd’s work into five key strands: New York, Paris, Africa, O'Keeffe and the walks across America. For each she wants to secure an exhibition and a photobook, she hopes that will secure Todd’s legacy. And so far it’s going pretty well, better than she ever expected.

“I’m well on my way now,” Betsy says, refilling our glasses. “The next is his Africa show – Out of the Frame – which will open in Minneapolis before travelling to Portland, Atlanta and hopefully beyond. Then the O’Keeffe show will tour the United States in 2021. The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston has confirmed they’ll do the walk across America in 2024. It’s only France I need to get some curator really jazzed about now, that’s my next goal. Then I feel like I will have done him justice.”

To do all this, Betsy has set herself a deadline. By the time she turns 70, she wants her work to be completed. By then, she hopes the movers and shakers in the industry – those collectors, curators and critics – will have the same revelatory moment that she did on first seeing Todd’s collection. “To experience that ‘oh my god what an amazing body of work’ feeling.”

According to Betsy, most celebrated photographers have their greatest hits: a handful of recognisable images which, upon being viewed by the right people are instantly attributable to the photographer who took them. When Betsy first met Todd, this didn’t apply to him. Now, she says, even that is changing. “One is The Circle which was taken on a hot day in Harlem, featuring kids dancing around a fire hydrant. Then there’s Sixth Avenue Between 43rd and 44th Streets taken in New York, 1948. It’s eight separate photographs, and really impressive. “

The second bottle of wine now close to empty, it’s time to call it a night, but not before I ask Betsy a final question: What’s her motivation to make sure the world is aware of the work of Todd Webb?

“It’s an honor to do what I do,” comes her reply, “although at times I’ve battled with the responsibility, the obligation.” But, Betsy says, she’s passed that now: “I’m on the home stretch, it’s the dream job, I’m feeling so confident, so happy, so hopeful. Some people never find their calling, and I certainly wasn’t seeking it. It’s just that everything I’ve done up until now has fitted this perfectly. I simply love Todd, and I love his work.”

The parallels in Todd and Betsy’s lives are strikingly obvious. There’s the geography: Colorado, San Francisco, New York and Portland, Maine were to each of real significance. And the importance to both of O’Keeffe and Stieglitz, too. But theirs are also both stories of people who searched long and hard to find fulfilment; for whom photography provided a lens through which to see the world. And, of course, both their lives have been defined by their unexpected and special friendship. To this day, when travelling to business meetings, Betsy carries with her a small box of Todd’s ashes to make sure he’s by her side.

“Three years before I moved to Portland, Maine. I hadn't even heard of Portland,” says Betsy, looking up at a photograph of Todd’s hanging next to a window. “Why did I end up here? When I did, why did I open a photography gallery? Why then did the Webbs walk into my life? I can’t tell you how or why, I just know it’s remarkable. Like I said earlier, I think it’s fate.”