An expedition is often judged on the grandeur of its scientific discoveries. But as writer Phoebe West discovered, the creative dispatches capturing the journey itself can be equally illuminating, whether from aboard Endurance—Ernest Shackleton’s ship that sank in the Antarctic in 1915—or the Endurance22 mission that discovered its wreck in 2022.

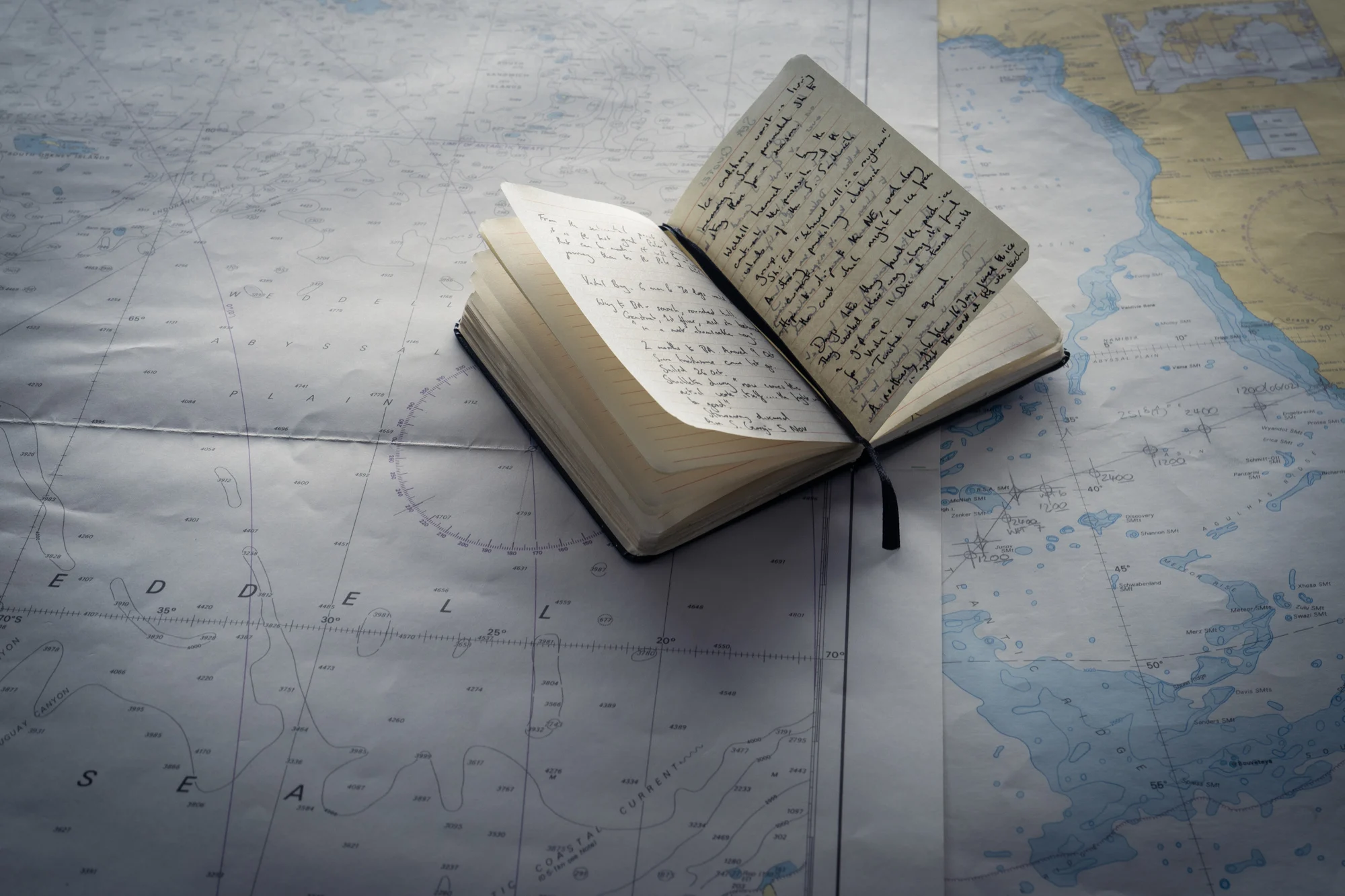

Humanity has left few environments unexplored. Thanks to modern technology, we have mapped the Mariana Trench and recorded stars whose light has taken 12.9 billion years to reach Earth. Historically, expeditions have been crucial to the collection of information deemed essential for our advance, and the pursuit of knowledge used to justify journeys across the world. Discovery can’t really be wielded as a motive in the same way today. But beyond data, what we find and how we translate it can transcend science to articulate the inarticulable. And what we create when we get there—from the photographs we take to the diaries we keep—allows for the building of connections through human experience beyond just events and places.

On February 5 2022, 110 people from around the world set sail from South Africa aboard the Agulhas II to complete the most complex subsea project ever undertaken. Using undersea drones to scan the Antarctic seabed, the team hoped to find the wreck of explorer Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance. Trapped beneath 10,000 feet of water and miles of sea ice, the 144-foot wooden ship, which sank in 1915, was famed as the most unreachable wreck in the world.

The site is protected as a historic monument under the terms of the Antarctic Treaty, signed in 1959 to preserve the continent. The goal of the search expedition, known as Endurance22, was to take photos, videos, and laser scans of the wreckage, but after four weeks of scouring the ocean floor, the prospect of finding it seemed less and less likely.

Then, on the afternoon of Saturday, March 5, the feeling onboard shifted, when miles of fiber optic cables presented the team with the images they had all been waiting for. Found just four miles south of where captain and navigator Frank Worsley recorded its last position on November 21 1915, they became the first people to see Endurance since it sank.

Protected from wood-eating organisms by the freezing water, Endurance sat peaceful and extant, the porthole of Shackleton’s cabin now adorned with sea anemones. On his blog, Mensun Bound, the expedition’s director of exploration, remarked that it was the most “bold and beautiful” wreck he had ever seen. “Most remarkable of all was her name – E N D U R A N C E – which arcs across her stern with perfect clarity,” he wrote.

Endurance’s original mission, known formally as the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, was to travel from London to the Weddell Sea, at the northernmost part of mainland Antarctica, from which point Shackleton and his team of 27 men would attempt to cross the continent from west to east. The voyage began on August 8 1914, but by the end of January 1915, Endurance was stuck in the Weddell’s impenetrable sea ice. Here, the ship drifted until November, when it finally succumbed to the pressure of the floes and sank to the seabed.

There began what is now one of the most famous journeys in history, which saw Shackleton and his men surviving in makeshift camps on the ice for months as they made their way north. In April 1916, they made the decision to sail to Elephant Island in lifeboats, wherefrom Shackleton and five of his men continued a further 800 miles to South Georgia. The rest of the crew were rescued in August of that year, but Endurance would remain unseen for more than a century.

It’s like a time-traveling expedition.

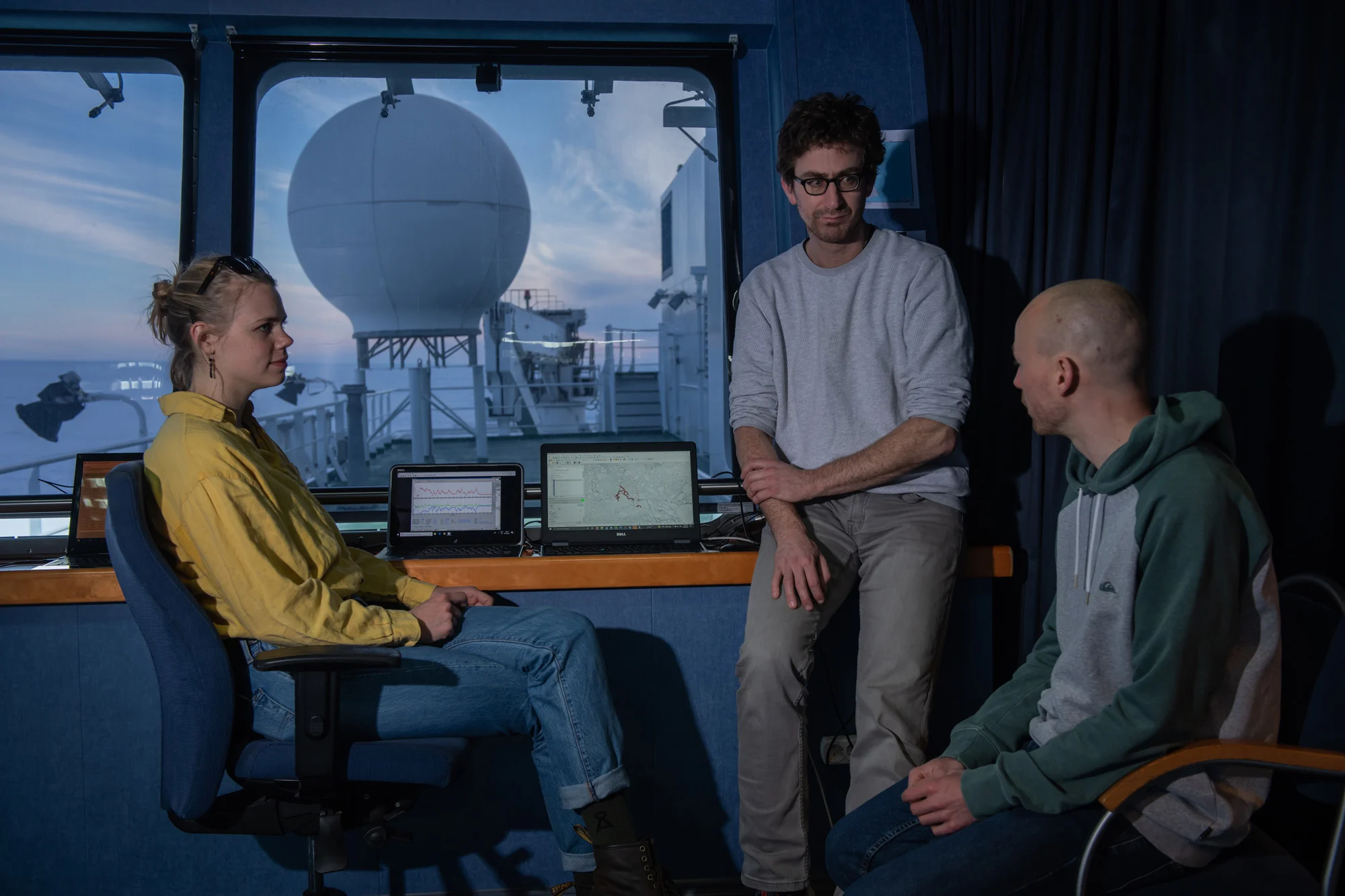

Aboard the Agulhas II was a creative team tasked with recording scenes of the expedition itself. Director Natalie Hewit, aerial cameraman James Blake, and cinematographer Paul Morris from British agency Little Dot Studios shot documentary footage, while producer Nick Birtwistle and presenter Saunders Carmicheal-Brown transmitted Endurance22’s progress for social media. “It was amazing to see audiences around the world engage with what we were doing in real time,” says Hewit. “If you give people the opportunity to engage and let them in, everyone can benefit.”

Photographing the expedition fell to Esther Horvath, who has been shooting scientific expeditions to polar regions since 2015. In 2020, she won a World Press Photo Award for her images of the Arctic. “For me, it’s like a time-traveling expedition,” she said. “We are in the wake of Shackleton, following his journey, and it’s a feeling of being in the footsteps of Frank Hurley.”

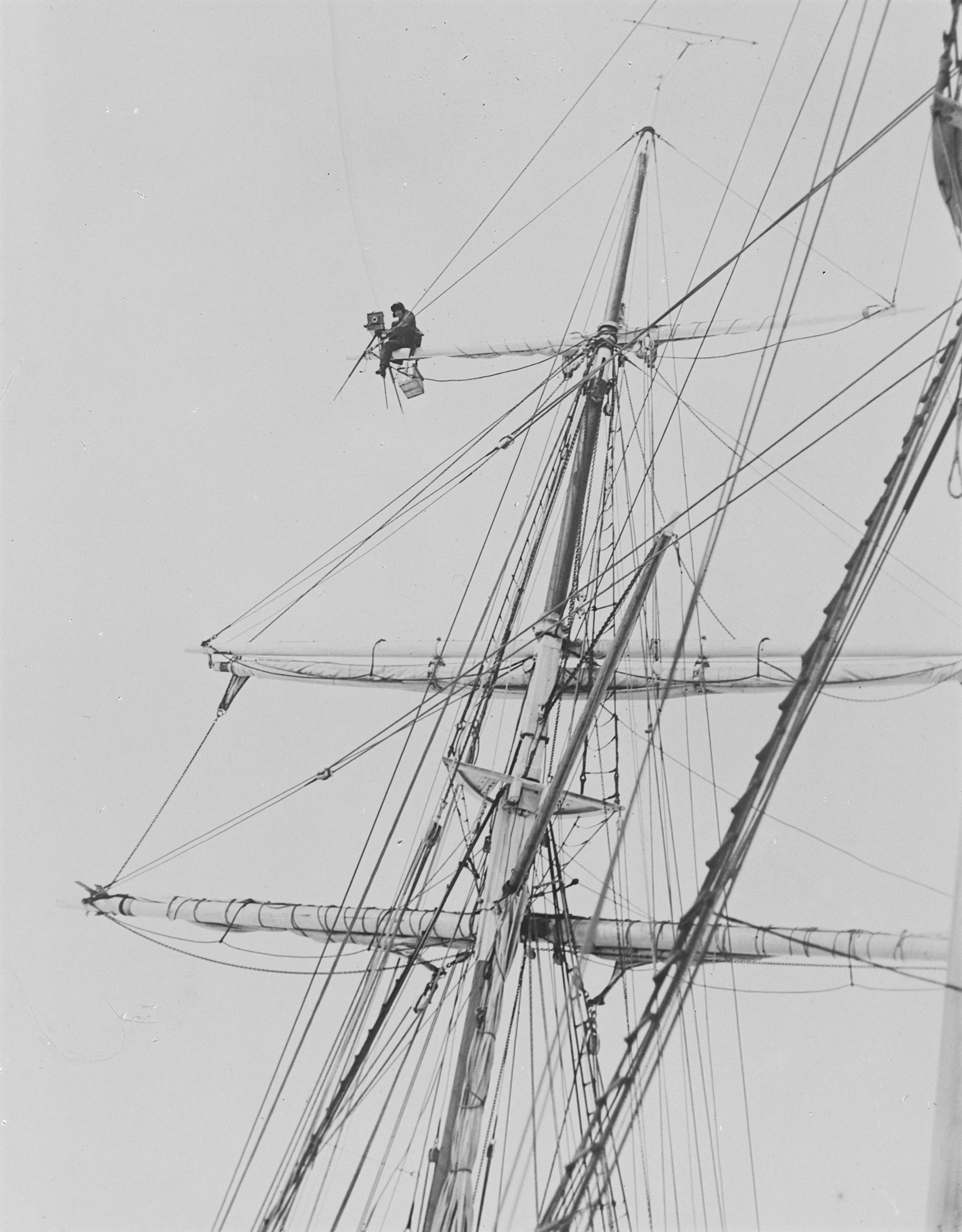

Hurley was the official photographer of the original Trans-Antarctic Expedition. According to the diaries of his fellow crew members, he could often be found in all manner of precarious positions on and off board in pursuit of a shot, or developing his plates in a DIY dark room he crafted from an upturned fridge. When Endurance finally went down, Shackleton ordered Hurley to leave his equipment and all but 150 of his negatives on board; and to smash his photographic plates before they set off, to prevent him from returning to the wreck. An exhibition of the incredible photographs of Frank Hurley taken on the original Endurance voyage are currently on display online at London’s Royal Geographical Society (with IBG).

“The last work done by our cinematographer, Frank Hurley, before his valuable camera was thrown away, was to film the masts of the Endurance as these were slowly twisted from her by the overpowering ice flows,” captain Frank Worsley recounted in his book, “Endurance: An Epic of Polar Adventure.” “So fine did he cut his distance that they swept within a few feet of where he was standing.”

Shackleton’s understanding of the importance of media for the success of expeditions was way ahead of his time.

When the men were rescued from Elephant Island months later and taken to Punta Arenas, Chile, Hurley immediately found the town’s leading photographer and commandeered his darkroom for three days, until all of his film and plates were processed.

Striking for their compositions and creativity, Hurley’s photographs brought a then little-explored part of the world to the public. More than that, they gave emotion and humility to a story that captured the public imagination. Just as he captured the structure of Endurance, the scenery it sailed through and, eventually, its sinking, Hurley photographed day-to-day life onboard. As well as official portraits of the men (and the dogs), he recorded their cleaning duties and haircuts, reading time before bed and tabletop games.

“Hurley’s work was our primary reference point…We were constantly studying his images, before and during the expedition,” says Endurance22 producer Paul Morris. “The story of the Endurance doesn’t exist without Hurley."

Though the Trans-Antarctic Expedition was unsuccessful, the rampant interest that followed Hurley’s photography proved there was more to be gained from expeditions than merely scientific reports. Human interest photography—as well as books, interviews, lectures, and other creative works inspired by such journeys—added an element of humanity that the public deeply connected with. The promise of engaging content would become increasingly vital to a mission’s success, helping leaders raise funding for prospective adventures and generate further income on their return.

“Shackleton’s understanding of the importance of media for the success of expeditions was way ahead of his time,” Hewit says. “He understood that people are unlikely to care about, or understand what you are doing unless it is documented and they can see it,” she says.

A poet, avid diarist, and romantic, Shackleton had deliberately sought out crew who possessed not only the right technical skills, but also creativity and joyfulness to join him on his trans-Antarctic endeavor. No single interview lasted more than five minutes, and the answer to the question “Can you sing?” could carry as much weight as those relating to a person’s physical fitness.

If you give people the opportunity to engage and let them in, everyone can benefit.

Today, these kinds of spaces and pastimes still play a massive part in shaping communities onboard.

“When you are all living, working, and traveling together, you become acutely aware of something being created between you—a bond of experience that no one else in the world has or can ever properly understand,” says Hewit. “That bond must inevitably find a way to express itself, whether it’s through in-jokes, nicknames, someone drawing cartoons or—as was the case on Endurance 22—re-writing the words to the Beatles’ song ‘Let It Be’ with lyrics about the expedition.”

When it comes to scientific research and exploration, the focus is placed upon the results and scale of discovery. But often, the journey is just as inspiring—not because of the frontiers crossed, but the spirit that perseveres.

“The finding of the Endurance was a collective effort, which shows the best of humanity…an international group of people from all over the world—the best in their respective fields—coming together to do something that has never been done before, something that pushes the boundaries of what we know and what we can do,” says Morris.

Shackleton understood that people are unlikely to care about, or understand what you are doing unless it is documented and they can see it.

Imagination would prove indispensable to the Endurance crew. While living on the ice, Shackleton’s men would share stories and fantasies to keep their brains active and wile away the hours. One of the personal items to survive the journey to Elephant Island was expedition artist George Marston’s “Penny Cookbook.” Each night, the men would pore over its pages, planning the elaborate meals they would have when they got home—a welcome distraction from their deteriorating physical health.

Before it sank, Endurance was home to “The Ritz,” a space where plays were performed, banquets held, concerts heard, and elaborate pranks played. Group activities like this were encouraged, and when the crew was forced to evacuate the ship with only essentials, Shackleton ordered meteorologist Leonard Hussey to bring his 12-pound zither banjo with him, knowing what music could do for morale.

Even on Elephant Island, when it would be difficult to fathom a bleaker set up, the men spent days preparing verses to be presented as a program of 26 acts to a wet hut of sleeping bags. They all pulled their weight and fulfilled their roles as expedition members, finding food, building shelters, and conducting lookouts, but the creativity each of them brought—from dressing up and writing poetry—connected them to each other and, upon their return to England, the rest of the world.