There’s a lot of stuff on the internet. Decades of blog posts, eBay listings, holiday photo albums and spam emails have led to our days being a constant onslaught of visual stimulation, from the ugly to the sublime, from the pixelated to mercurial HD. Duncan Poulton knows this better than most. He trawls the web for the long-forgotten imagery—the stuff the algorithms probably wouldn’t have shown you otherwise—and creates vast digital collages. He tells Madeleine Morley that his busy pieces are intended to create the same disorientating, intense experience that the over-abundance of the web can create in us every day.

Duncan Poulton is sifting through trash.

It’s not just any old trash, either. It’s what he calls “digital trash”—the enormous quantity of content that users upload into the world every day without so much as a second thought, accumulating like waste around the web.

He’s surfing through Wiki Commons, through old eBay listings and random 3D modeling websites, downloading arbitrary, poor quality images that catch his eye and filing them away in neatly arranged folders on his desktop. In many ways, Duncan is a digital dumpster diver—recovering the things that no one has deemed worthy enough to even remember to delete, and repurposing these collected fragments into digital collages. In these rearranged forms, the forgotten finds new meaning and life.

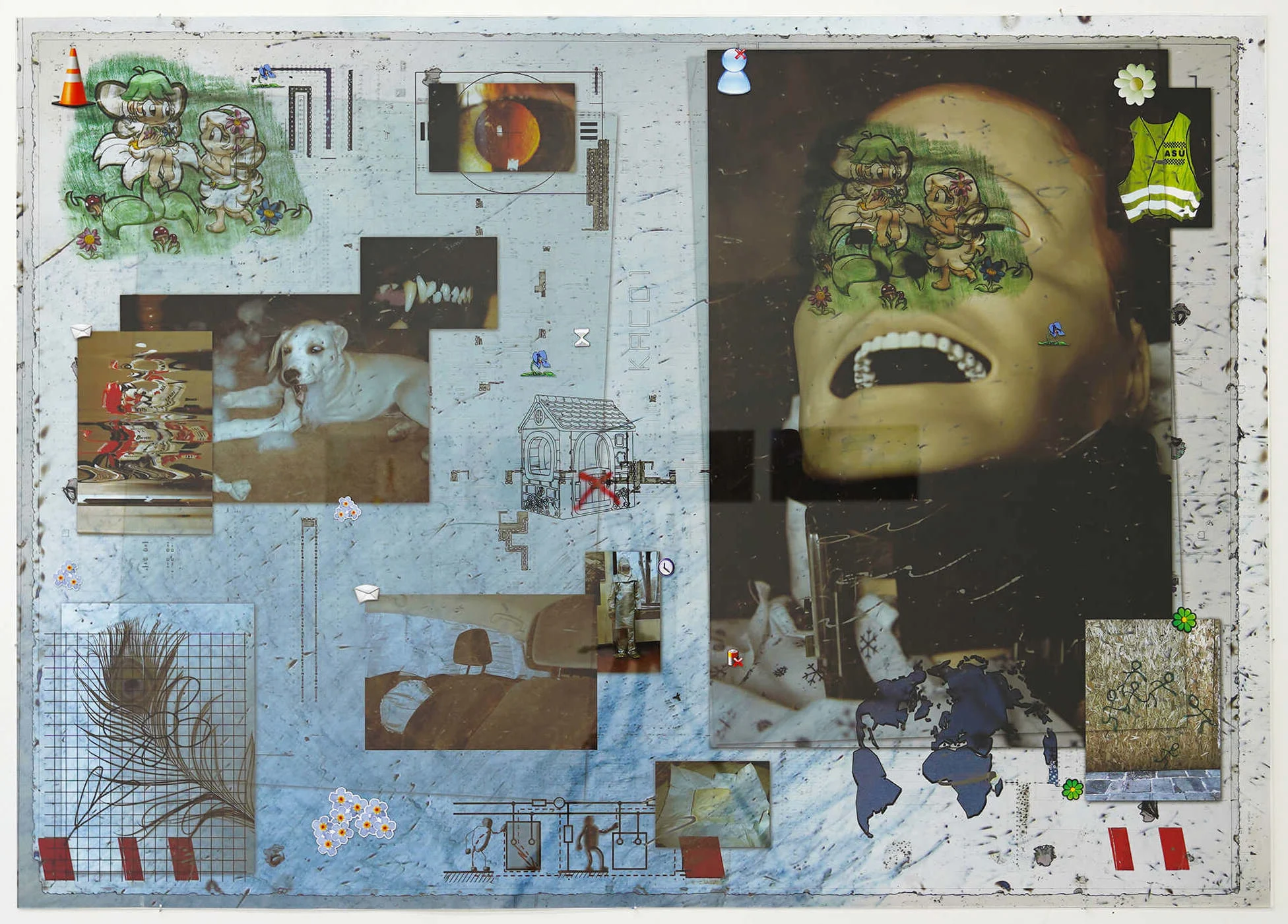

Take his work “Mortal Song” as an example. For it, Duncan digitally assembled some of the “trash” he’s recently collected: A scan of a children’s drawing sits beside a close-up of dog’s teeth and a flash photograph of a reflective bib. Small emoji-like cartoons scatter across the grimy artwork.

Looking at all of these images—each of which once belonged to the backpages of personal blogs or pet forums—crammed together feels intense and disorientating. There’s too much to look at, and it’s sickening, almost like you’ve spent an entire day in a darkened room surfing strange corners of the net.

I specifically wanted to find the content algorithms don’t want you to find.

“The first work I made using ‘digital trash’ appropriated a camcorder unboxing video I found on YouTube, which had about 10 views,” says Duncan from his home in South London. That was back in 2014, when he was completing his BA in Fine Art Critical Practice at the University of Brighton. It was one YouTuber’s careful, ceremonial unwrapping and poignant voice-over describing an entirely outdated camera that stood out to Duncan. For the artist, videos like this one are a form of “digital trash” because they document an obsolete item of technology no longer relevant to most, hence generating very few views. And just like waste in the real world, these irrelevant videos stick around and take up digital space.

After discovering the video, Duncan set himself a rule that he’d only use digital material that didn’t have a huge amount of views or likes in his work, interested in what that could reveal about the underbelly of the web. “I specifically wanted to find the content algorithms don’t want you to find,” says Duncan. Algorithms are aware of when digital content is no longer relevant to most people, and they know when something is timely. They also know how to promote quality images. Images that aren’t high resolution, or that belong to outdated pages or platforms, inevitably get buried by search engines, as they aren’t deemed sufficiently profit-generating to prioritize.

A scroll through Duncan’s collection of material, saved in carefully arranged folders, reveals the ghostly strata that he’s so fascinated by: Blurry flash photography of used Fisher Price toys once on sale sit next to sparkling flower gifs from the early days of Web 2.0 and scans of chaotic drawings uploaded onto uninhabited forums. “Quite often, I wonder, ‘why has someone gone through the effort of taking this image and thinking they want to share it with the world?’” says Duncan.

And so he takes these images, and rearranges and edits them using software like Photoshop. Reassembled, these pieces tell the viewer a lot about what everyday life on the internet looks like—what we collectively consume, what we spend our days uploading, and then what we forget when we move onto the next new thing.

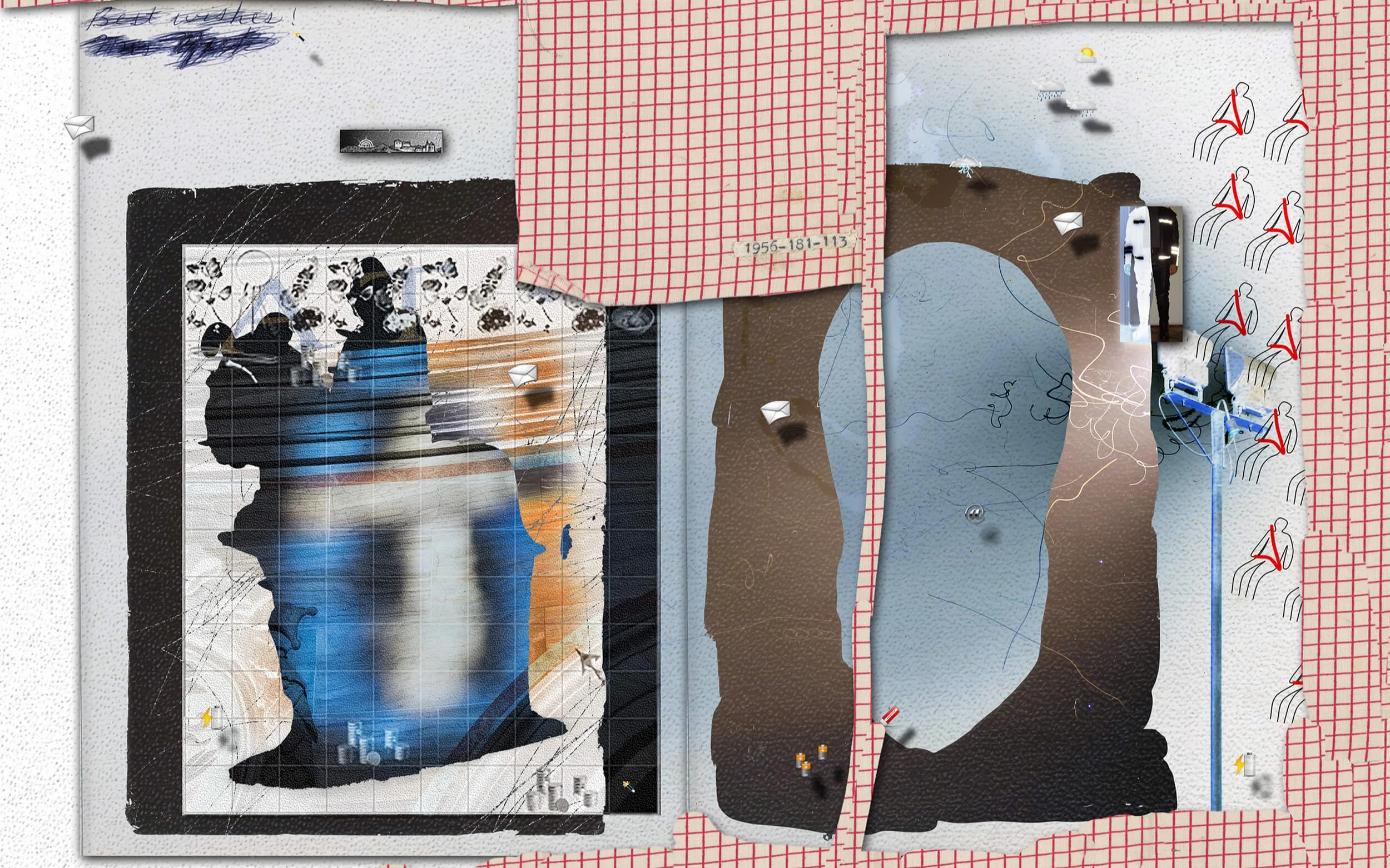

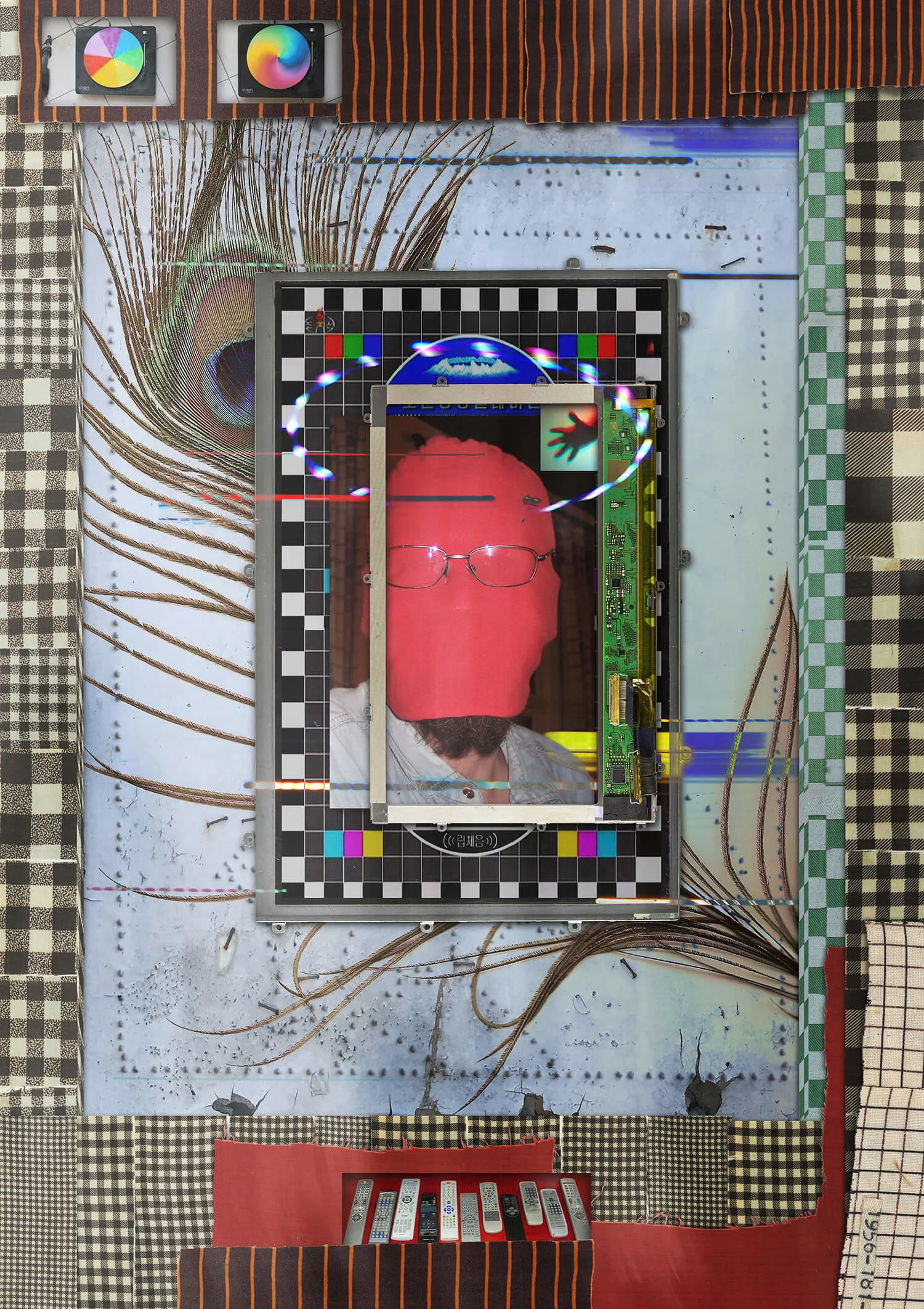

In one of his most recent artworks, “St. Anonymous,” a found photograph of a white, bearded man’s largely covered face, overlaid with glasses, is placed inside a series of framing devices made from swatches from Smithsonian textile scans and uploads of TV test patterns, coming together to evoke the composition of a traditional icon painting. “I was originally thinking of it as an ode to the anonymous uploader,” says Duncan—ie. the people who uploaded all the “digital junk” that inspires Duncan.

When you sit down at the end of the day and your eyes are tired, your mind is full of a thousand images and bits of information.

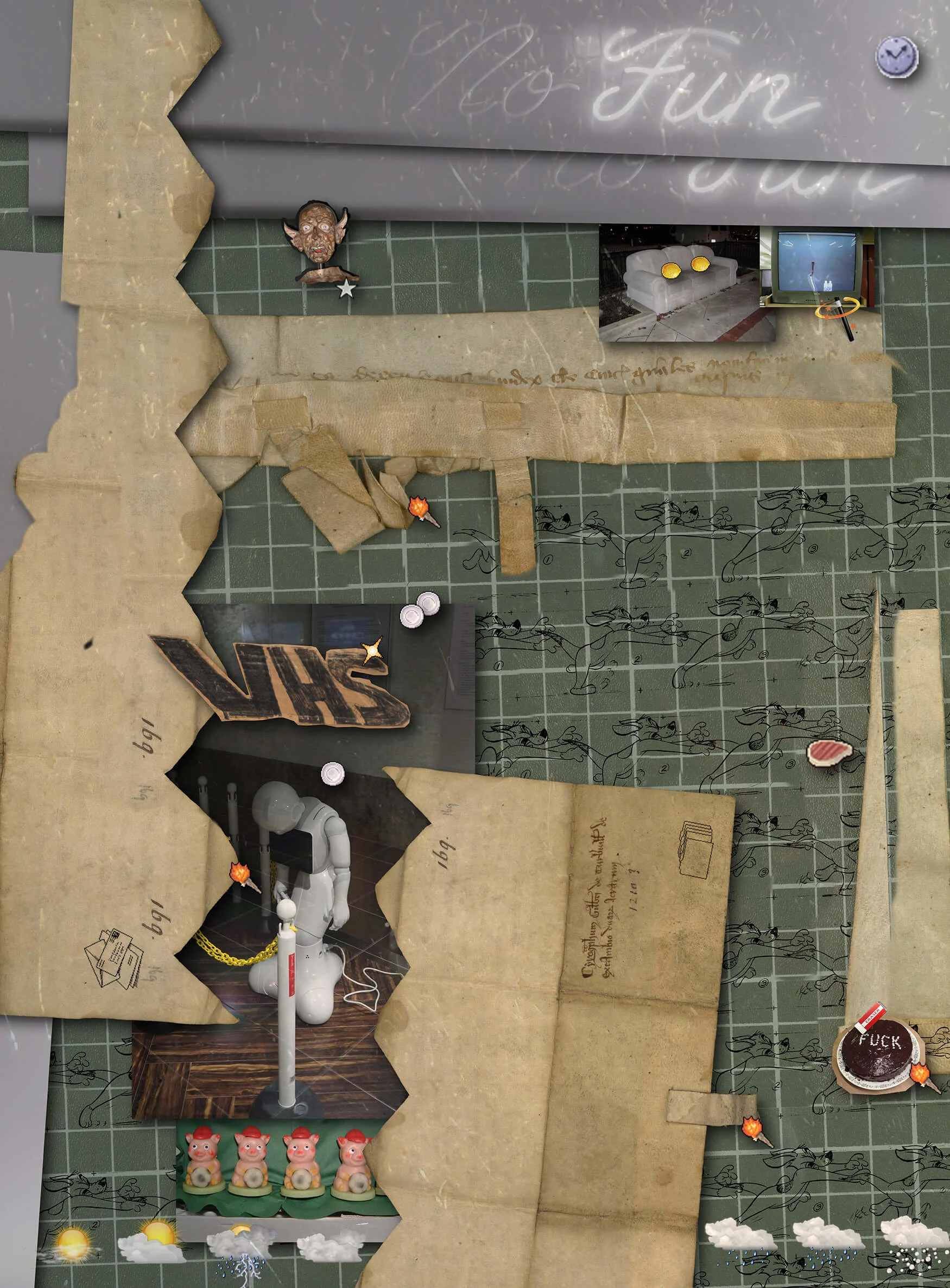

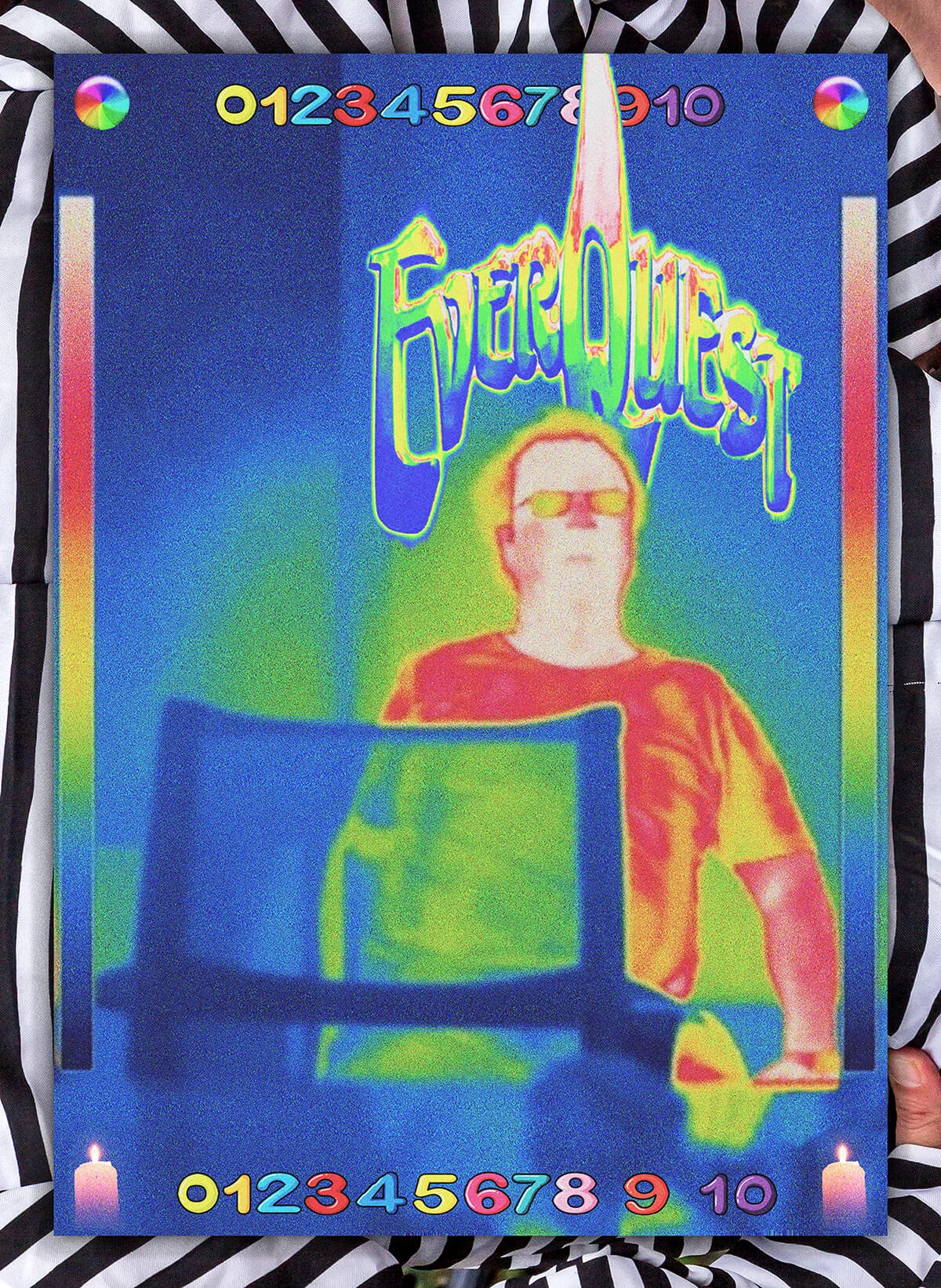

“Nuclear Summer (Everquest)” similarly combines disjunctive images to form a reflection on life during lockdown. “I had just moved back to my parents’ house in Birmingham, and was living this hermetic existence in my teenage bedroom,” says Duncan. “I made this particular work during the hot summer where we still had to be indoors.”

Duncan found a low-res infrared scan, featuring a man testing out his infrared equipment from his desk, an image that “resonated a lot” with his current situation. He spliced the file together with a warped EverQuest logo, the late-90s 3D fantasy game. “I wanted to capture this feeling of a never ending online existence, to resonate with what many of us were living through,” he says. Two Mac “spinning wheels of death” puncture the top of the work, because as Duncan was making it—filtering his found infrared scan over and over again—his computer kept dying. “I then noticed the loading symbol had the same colors,” he says.

And what can we ultimately read in Duncan’s juxtapositions of images found in the subterranean depths of the net? “I suppose the works pay witness to the lives that we lead now,” he says. “When you sit down at the end of the day and your eyes are tired, your mind is full of a thousand images and bits of information.” It’s this whirring chaos of the subconscious struggling against overabundance that he attempts to capture. While his artworks may seem bleak, in a way, they quite accurately reflect the messy everydayness of collective life online. As Duncan says: “I call it digital grubbiness.”