Though often whimsical and colorful in their presentation, Turkish artist Dilara Şahin’s experimental collages explore the darker side of life. Even when the photographs used carry a more optimistic energy, the overlaid text makes us think twice about their tone, introducing heavier themes—isolation, sadness, death and loss. She tells Alia Wilhelm how she uses her collages to process the more difficult emotions that life has led her to and how, despite the world’s hunger for more positive images representing “the good life,” she plans to keep doing what comes naturally to her, creating work that reflects the world as she sees it.

Collage artist and photographer Dilara Şahin is home in Balıkesir, Turkey, where she has spent the better part of the year alone. When she returned here in 2022 after seven years in Moscow, her outsiderness felt more acute than it did abroad. “At least in Russia it was obvious that I was a foreigner,” she explains. “To be home and to be Turkish but still an alien, that is more difficult.”

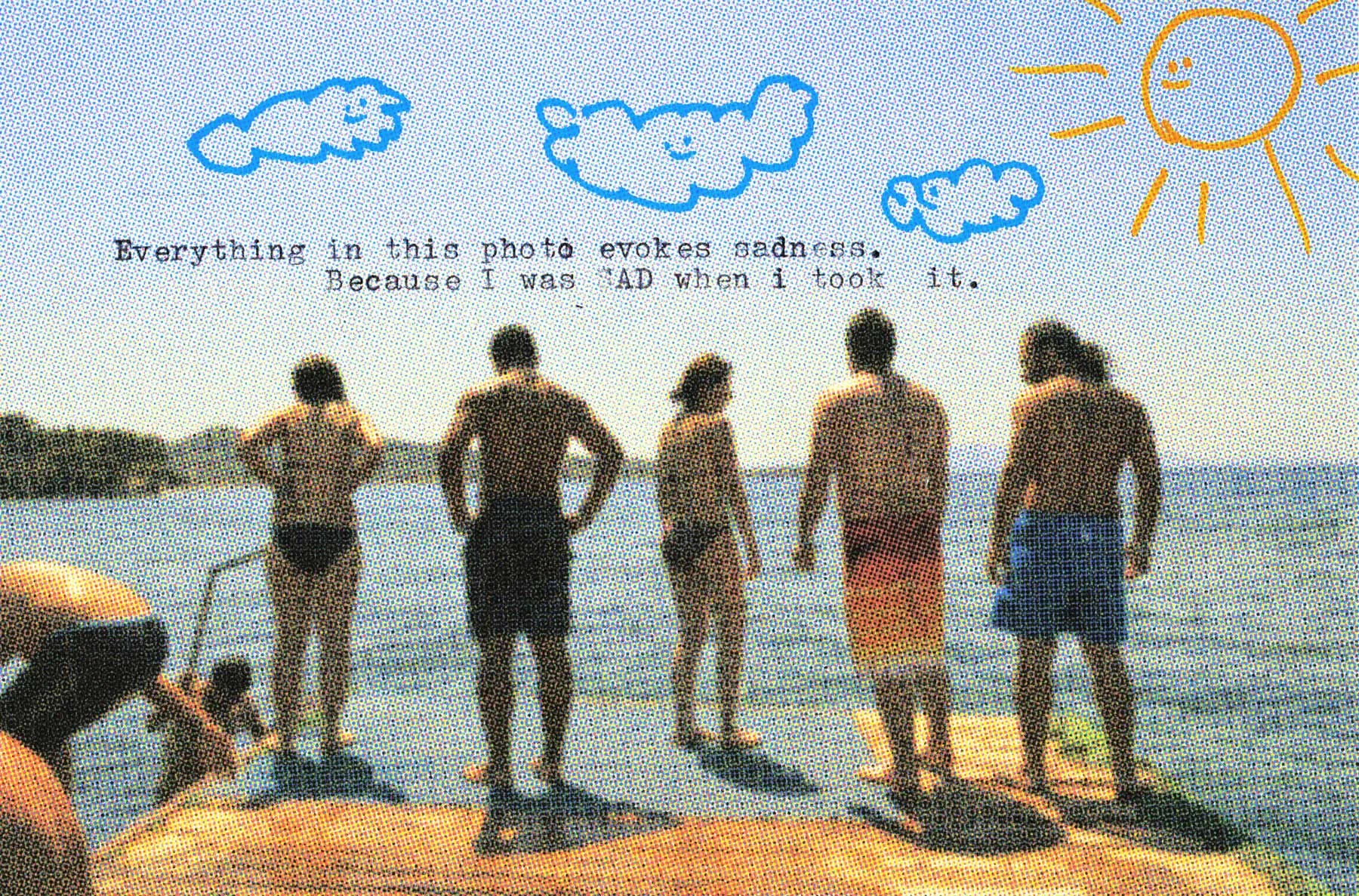

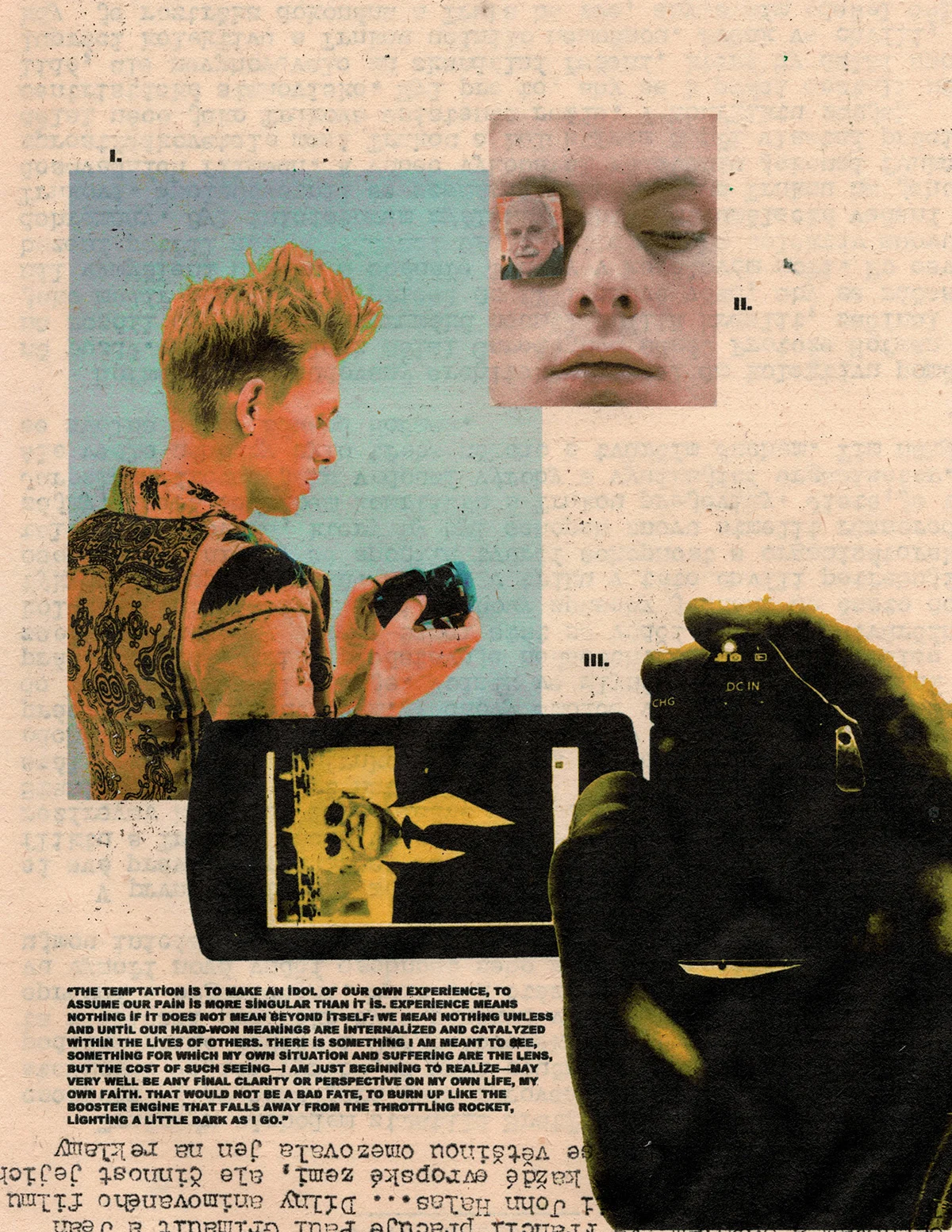

Şahin uses film stills or her own cinematic, high-contrast imagery to create experimental collages reminiscent of the 60s and 70s. “Today’s aesthetic doesn’t interest me. When everything is clean, it’s predictable,” she says. Though she uses a digital camera and some photo-editing is carried out on her computer, she prints on archival paper to further embellish the work by hand. Holding up the yellowed cover of an old Yiddish book, she explains, “I find paper in second-hand shops, and I print on the first and last pages of books.”

It has been challenging to find a home for her work in Turkey, since publications favor glossy images that accentuate beauty. “The mainstream narrative is about selling the idea of a good life,” Şahin explains, which puts her in a bind since beauty and positivity are never the point of her work. If anything, it is pain she hopes to explore in her collages. “I’m not a ‘Life is great!’ type of person, since some of the things I experienced during my childhood removed this illusion,” she says. “When you’re eight or nine but faced with the dark side of life, it’s impossible to be much of an optimist.”

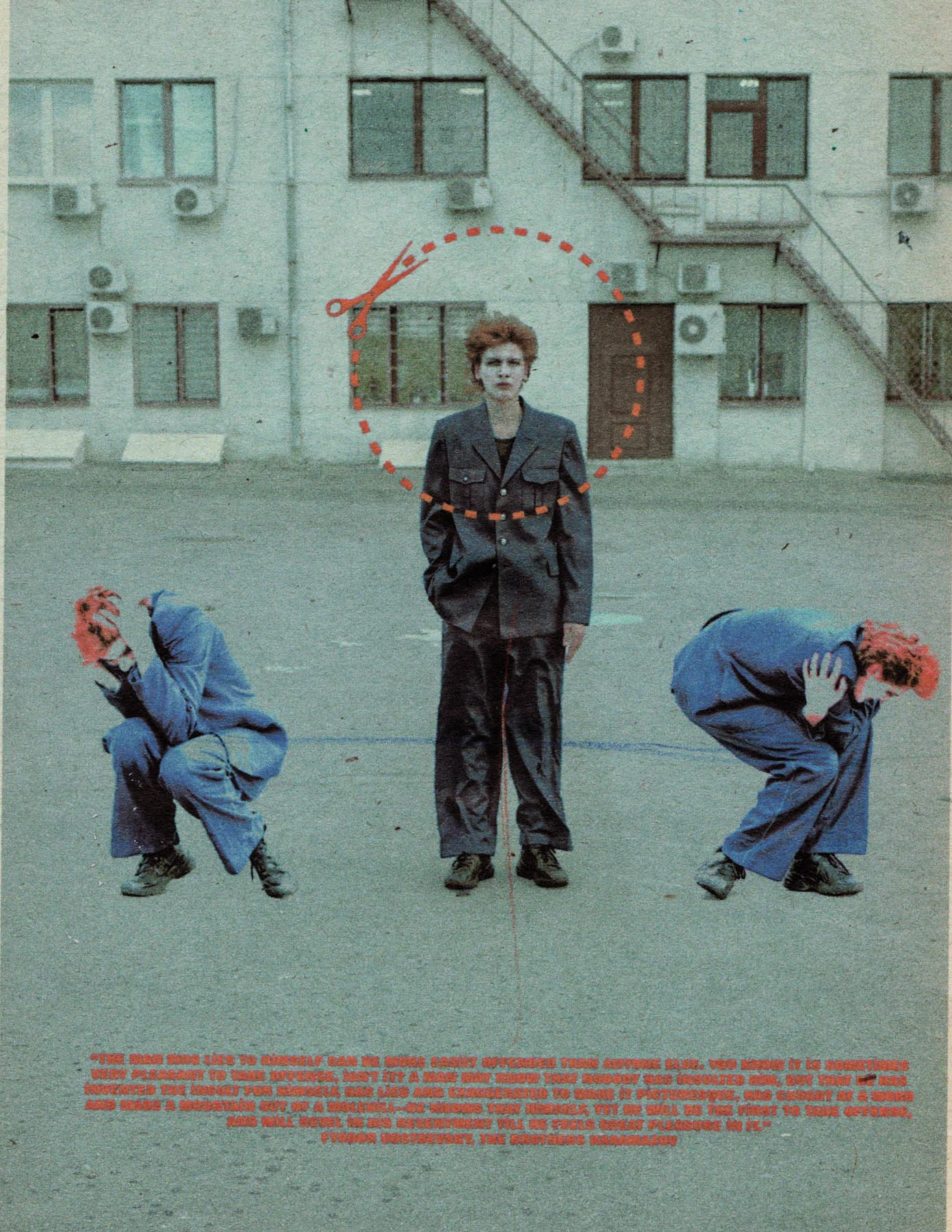

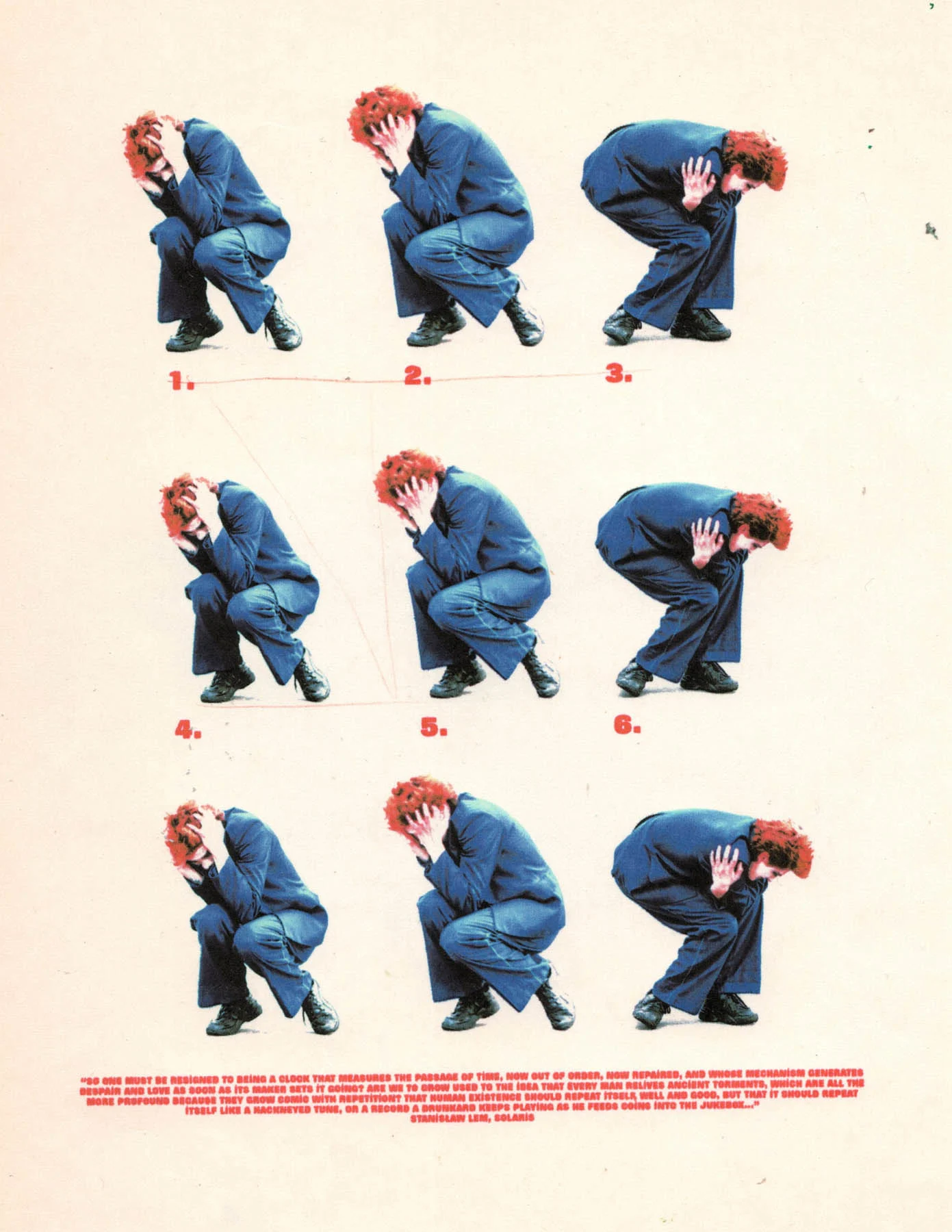

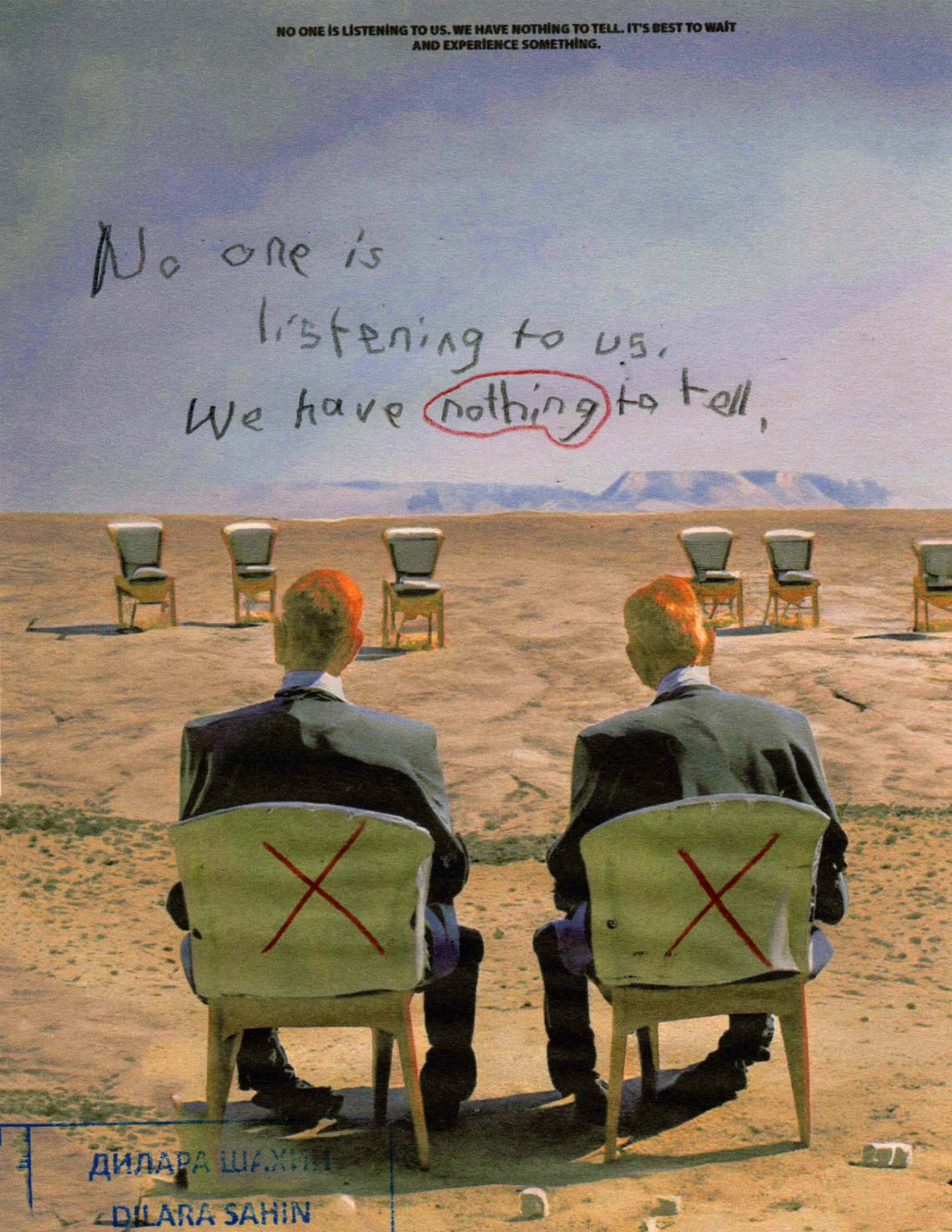

The war in Russia changed Şahin’s work, too: “I realized the things we dream of can crumble suddenly, that the people we know can disappear in a day. Now I think the only true things in life are death and love.” This perspective is evident in her collages, where double-page spreads reminiscent of magazine layouts abound, but the captions touch on transience and suffering. One collage is accompanied by a quote on self-deception, borrowed from Dostoevsky’s “The Brothers Karamazov.” Another includes a passage from Stanisław Lem’s sci-fi novel, “Solaris,” on the cyclical nature of suffering.

Though the war in Russia prompted Şahin’s departure, she feels her current freedoms are similarly limited in Turkey: “I can’t express myself here, and I don’t want to spend my energy trying to be accepted,” she says. These feelings of alienation gave rise to her series, “The Desert Project.” Though whimsical and vivid, the collages speak to her experience of being unheard and isolated. “I got the inspiration from living in a place where no one listened to anyone, and I often found myself lost for words. I looked in the mirror and saw that I was alone,” she says.

Because Şahin’s work is inspired by emotion, her process is spontaneous. “The person I’m photographing has no importance to me. The only thing that gets me in motion is anger, sadness or feeling stuck. I rarely plan a shoot in advance,” she says. This explains why she usually photographs her friends: They are available at a moment’s notice if she’s overtaken by some keen urge, hellbent on processing the sensation before it has a chance to slip away.

Many of her collages reference films—”North by Northwest” and “Wings of Desire”—or contain quotes by writers, filmmakers and philosophers such as Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre and Virginia Woolf. Inserted into the punchy, high-contrast collage, “My Eyes Always Search for You,” for example, is a quote on suffering by Christian Wiman. “We are blind to our own personality, deaf to our own voice. This is the message I intended to share,” Şahin says. The result is that engaging with her work is to be carried simultaneously inward and outward, drawn both into her self-reflections and cast out into the hearts and minds of those who have come before her.

If her work is denotative, then this is a quality it shares with Soviet art, which Şahin considers rich and referential: “[The Soviets] weren’t a people that were especially lucky. Their freedom of thought was obstructed. As a Turkish citizen, this feels familiar to me.” It is Russian writer Dostoevsky, though, who moves her most, since she has always been more on the side of the poor, of people without. Perhaps this is because she sees herself as a part of, not apart from, everything. “I am very aware of the fact that I am no one, that I am a small part of everything and everyone,” she says.